Mary Cassatt facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mary Cassatt

|

|

|---|---|

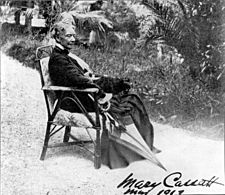

Cassatt seated in a chair with an umbrella, 1913. Verso reads "The only photograph for which she ever posed."

|

|

| Born |

Mary Stevenson Cassatt

May 22, 1844 Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, U.S.

|

| Died | June 14, 1926 (aged 82) Château de Beaufresne, near Paris, France

|

| Education | Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Jean-Léon Gérôme, Charles Chaplin, Thomas Couture |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Impressionism |

| Signature | |

Mary Stevenson Cassatt (May 22, 1844 – June 14, 1926) was an American painter and printmaker. She was born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania (now part of Pittsburgh), but lived most of her life in France. There, she became friends with Edgar Degas and showed her art with the Impressionists. Cassatt often painted scenes of women's lives, especially the close connection between mothers and children.

People like Gustave Geffroy called her one of the "three great ladies" of Impressionism. The other two were Marie Bracquemond and Berthe Morisot. In 1879, another art expert, Diego Martelli, compared her to Degas. He said they both tried to show movement, light, and modern design in their art.

Contents

Early Life and Art Training

Mary Cassatt was born in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, which is now part of Pittsburgh. Her family was well-off. Her father, Robert Simpson Cassatt, was a successful stockbroker. Her mother, Katherine Kelso Johnston, came from a banking family. Katherine was educated and loved to read, and she greatly influenced Mary. Mary's friend, Louisine Havemeyer, said that Mary got her artistic talent from her mother.

Mary was one of seven children. Her family believed that travel was important for education. She spent five years in Europe, visiting cities like London, Paris, and Berlin. During this time, she learned German and French. She also had her first drawing and music lessons. She likely saw works by famous French artists like Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres and Gustave Courbet at the Paris World's Fair in 1855. Artists like Edgar Degas and Camille Pissarro, who later became her friends, were also there.

Starting Art School

Even though her family didn't want her to be a professional artist, Cassatt started studying painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia when she was just 15. Her parents worried about her being exposed to new ideas about women's rights and the free-spirited behavior of some male students. Cassatt and her friends were strong supporters of equal rights for women throughout their lives.

About 20% of the students at the Academy were female. However, most saw art as a hobby, not a career. Cassatt, though, was determined to make art her life's work. She studied there from 1861 to 1865, during the American Civil War.

Cassatt became impatient with the slow teaching and the way male students and teachers treated her. She decided to study the old masters on her own. She later said there was "no teaching" at the Academy. Female students couldn't use live models until later, and most of the training was drawing from plaster casts.

Moving to Paris

Cassatt decided to leave the Academy since no degree was given. After convincing her father, she moved to Paris in 1866. Her mother and family friends went with her as chaperones. Women could not yet attend the famous École des Beaux-Arts. So, Cassatt studied privately with teachers from the school, like Jean-Léon Gérôme. He was known for his very realistic paintings.

Cassatt also improved her art by copying paintings daily at the Louvre. She needed a special permit to do this. The museum was also a social place for Frenchmen and American female students. Women like Cassatt were not allowed in cafes where artists often met.

In 1868, one of her paintings, A Mandoline Player, was accepted by the jury for the Paris Salon. This was a very important art show. Cassatt and Elizabeth Jane Gardner were the first two American women to show their art at the Salon that year. A Mandoline Player was in the Romantic style. Cassatt continued to show her work at the Salon for over ten years, but she became more and more frustrated.

Challenges Back Home

In late 1870, as the Franco-Prussian War began, Cassatt returned to the United States. She lived with her family in Altoona. Her father still didn't support her art career. He paid for her basic needs but not her art supplies. Cassatt showed two paintings in a New York gallery. Many people admired them, but no one bought them. She was also upset by the lack of art to study. She even thought about giving up art.

Cassatt went to Chicago to try her luck, but she lost some of her early paintings in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Soon after, her work caught the eye of Bishop Michael Domenec of Pittsburgh. He asked her to copy two paintings by Correggio in Parma, Italy. He gave her enough money for her travel and part of her stay. She was very excited to get back to painting. With Emily Sartain, another artist, Cassatt set off for Europe again.

Joining the Impressionists

Within months of returning to Europe in late 1871, Cassatt's luck changed. Her painting Two Women Throwing Flowers During Carnival was well-liked at the 1872 Salon and was bought. People in Parma praised her art.

After finishing the bishop's request, Cassatt traveled to Madrid and Seville. There, she painted Spanish subjects, like Spanish Dancer Wearing a Lace Mantilla (1873). In 1874, she decided to live in France. Her sister Lydia joined her, and they shared an apartment. Cassatt opened a studio in Paris. She continued to criticize the Salon's rules and old-fashioned tastes.

Cassatt saw that art by women was often ignored unless the artist had a friend on the jury. She refused to try to win over the jurors. Her frustration grew when one of her paintings was rejected in 1875, only to be accepted the next year after she made the background darker.

Meeting Degas and the Impressionists

In 1877, both of Cassatt's paintings were rejected by the Salon. At this low point, Edgar Degas invited her to show her work with the Impressionists. This group had started their own independent art shows in 1874. The Impressionists were also called "Independents." They didn't have strict rules and used different subjects and styles. They liked painting outdoors and using bright colors in separate brushstrokes. This made the viewer's eye blend the colors, creating an "impression." Critics had been very harsh on the Impressionists for years.

Cassatt admired Degas. His pastel drawings had deeply impressed her when she saw them in a gallery in 1875. She said, "I used to go and flatten my nose against that window and absorb all I could of his art. It changed my life. I saw art then as I wanted to see it." She eagerly accepted Degas' invitation. She started preparing paintings for the next Impressionist show in 1879. She felt comfortable with the Impressionists and joined their cause with excitement. She hoped to sell her paintings to people in Paris who liked new art. Her style became more natural. She started carrying a sketchbook to draw scenes she saw outdoors or at the theater.

In 1877, Cassatt's parents and sister Lydia joined her in Paris. They all shared a large apartment. Mary valued their company, as neither she nor Lydia had married. Mary had decided early on that marriage would not fit with her career. Lydia, who often posed for her sister, was often sick. Her death in 1882 made Cassatt unable to work for a while.

Cassatt's father insisted that her art sales should cover her studio and supplies. Since her sales were still small, Cassatt worked hard to create good paintings for the next Impressionist show. Three of her best works from 1878 were Portrait of the Artist (a self-portrait), Little Girl in a Blue Armchair, and Reading Le Figaro (a portrait of her mother).

Degas had a big influence on Cassatt. Both artists liked to experiment with materials, trying different paints. Cassatt became very skilled with pastels, creating many important works in this medium. Degas also taught her etching, a skill he was very good at. They worked together for a time, and her drawing skills greatly improved with his help.

The Impressionist show of 1879 was their most successful yet. Cassatt showed eleven works, including Lydia in a Loge, Wearing a Pearl Necklace. Critics said Cassatt's colors were too bright and her portraits too realistic. However, her work was not attacked as harshly as Monet's. She used her share of the profits to buy a painting by Degas and one by Monet. She continued to participate in Impressionist exhibitions until 1886. In 1886, Cassatt sent two paintings to the first Impressionist exhibition in the US. Her friend Louisine Elder married Harry Havemeyer in 1883. With Cassatt's advice, they started collecting Impressionist art on a large scale. Much of their collection is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

Cassatt also painted several portraits of her family during this time. Portrait of Alexander Cassatt and His Son Robert Kelso (1885) is one of her most famous. After 1886, Cassatt no longer identified with any art movement and tried different techniques.

Mary Cassatt and the "New Woman"

Mary Cassatt and other women artists of her time benefited from new ideas about women's rights in the 1840s. This allowed them to attend colleges and universities that were starting to accept both men and women. Women's colleges also opened during this period. Cassatt strongly supported equal rights for women. She campaigned for equal travel scholarships for students in the 1860s and the right to vote in the 1910s.

Mary Cassatt showed the "New Woman" of the 19th century from a woman's point of view. As a successful, well-trained artist who never married, Cassatt was an example of the "New Woman." She helped change how women were seen in art. This was influenced by her intelligent and active mother, Katherine Cassatt, who believed women should be educated and involved in society. Her mother is shown in the painting Reading 'Le Figaro' (1878).

Cassatt didn't make direct political statements about women's rights in her art. However, her paintings of women always showed them with dignity and a sense of deep inner life. Cassatt didn't like being called a "woman artist." She supported women's suffrage (the right to vote). In 1915, she showed eighteen works in an exhibition to support the movement. This show was organized by Louisine Havemeyer, who was a strong supporter of women's rights. The exhibition caused problems with Cassatt's sister-in-law, Eugenie Carter Cassatt, who was against women voting. Eugenie and other people in Philadelphia society boycotted the show. In response, Cassatt sold off her work that was meant for her family. For example, The Boating Party, which was thought to be inspired by the birth of Eugenie's daughter, was bought by the National Gallery in Washington D.C.

Working with Degas

Cassatt and Degas worked together for a long time. Their art studios were close to each other in Paris. Degas often visited Cassatt's studio to offer advice and help her find models.

They had much in common. They liked similar art and books, came from wealthy families, and had studied painting in Italy. Both were independent and never married. Degas taught Cassatt about pastel and engraving, which she quickly mastered. Cassatt, in turn, helped Degas sell his paintings and made him more famous in America.

Both artists saw themselves as painters of people. Art experts believe they were influenced by art critic Louis Edmond Duranty. He wanted to see a new kind of figure painting that showed "the characteristic modern person in his clothes, in the midst of his social surroundings."

After Cassatt's parents and sister Lydia joined her in Paris in 1877, Degas, Cassatt, and Lydia often went to the Louvre together to study art. Degas made two prints showing Cassatt at the Louvre looking at art while Lydia read a guidebook. Cassatt often posed for Degas, especially for his series of paintings showing women trying on hats.

Around 1884, Degas painted an oil portrait of Cassatt called Mary Cassatt Seated, Holding Cards. A Self-Portrait (c. 1880) by Cassatt shows her wearing the same hat and dress. This suggests they might have painted each other during the same session.

Cassatt and Degas worked most closely in late 1879 and early 1880. This was when Cassatt was perfecting her printmaking skills. Degas owned a small printing press. She worked at his studio during the day, using his tools. In the evenings, she made sketches for the etching plate she would work on the next day. However, in April 1880, Degas suddenly quit a prints journal they were working on. Without his support, the project stopped. Degas' decision upset Cassatt, who had worked hard on a print called In the Opera Box for the journal.

Even though Cassatt always had warm feelings for Degas, she never worked as closely with him again. Degas was very direct in his opinions, just like Cassatt. They disagreed about the Dreyfus Affair, a political scandal in France. From the 1890s onward, their relationship became more about business. Still, they continued to visit each other until Degas died in 1917.

Later Life and Art

Mary Cassatt is famous for her many carefully drawn and gentle paintings and prints of mothers and children. The earliest dated work on this topic is the drypoint print Gardner Held by His Mother (1888). Some of these works show her own family or friends. In her later years, she often used professional models. These paintings sometimes remind people of Italian Renaissance art showing the Madonna and Child. After 1900, she focused almost entirely on mother-and-child subjects, like Woman with a Sunflower. It might surprise some that even though she painted many mother-child pairs, Cassatt herself chose not to marry or have children.

The 1890s were Cassatt's busiest and most creative time. She became more mature and less blunt in her opinions. She also became a role model for young American artists who sought her advice.

In 1891, she showed a series of very original colored drypoint and aquatint prints. These included Woman Bathing and The Coiffure. She was inspired by Japanese art that had been shown in Paris the year before. Cassatt liked the simple and clear designs of Japanese art and their clever use of color blocks. In her own prints, she used mostly light, soft pastel colors and avoided black. Experts say these colored prints are her most original contribution to art.

Also in 1891, a businesswoman from Chicago named Bertha Palmer asked Cassatt to paint a large mural for the Women's Building at the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893. Cassatt worked on this project for two years while living in France with her mother. The mural was a triptych, meaning it had three parts. The main part was called Young Women Plucking the Fruits of Knowledge or Science. The left panel was Young Girls Pursuing Fame, and the right panel was Arts, Music, Dancing. The mural showed women as successful individuals, not just in relation to men. Palmer thought Cassatt was an American treasure and the perfect person to paint a mural for an exhibition that would highlight the status of women. Sadly, the mural was torn down after the exhibition. However, Cassatt made other studies and paintings with similar themes, so we can still see her ideas.

As the new century began, Cassatt advised several important art collectors. She asked them to eventually donate their art to American museums. In 1904, France honored her with the Légion d'honneur for her contributions to art. Even though she helped American collectors, her art was recognized more slowly in the United States.

Mary Cassatt's brother, Alexander Cassatt, was president of the Pennsylvania Railroad until he died in 1906. She was very close to him, and his death affected her deeply. Still, she continued to be very productive until about 1910. Her later work became more sentimental. Her art was popular with the public and critics, but she was no longer creating new styles. Her Impressionist friends, who once inspired her, were dying. She did not like new art movements like post-Impressionism or Cubism. Two of her mother-and-child paintings were shown in the Armory Show of 1913.

A trip to Egypt in 1910 impressed Cassatt with the beauty of ancient art. But it was followed by a creative crisis. The trip exhausted her, and she felt "crushed by the strength of this Art." She said, "I fought against it but it conquered, it is surely the greatest Art the past has left us... how are my feeble hands to ever paint the effect on me." In 1911, she was diagnosed with diabetes, rheumatism, neuralgia, and cataracts. She kept working, but after 1914, she had to stop painting because she became almost blind.

Mary Cassatt died on June 14, 1926, at Château de Beaufresne, near Paris. She was buried in her family's vault in Le Mesnil-Théribus, France.

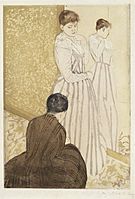

Images for kids

Legacy

- Mary Cassatt inspired many Canadian women artists, including those in the Beaver Hall Group.

- The SS Mary Cassatt was a World War II Liberty ship, launched on May 16, 1943.

- A group of young string musicians from the Juilliard School formed the all-female Cassatt Quartet in 1985, named after the painter.

- In 1966, Cassatt's painting The Boating Party was shown on a US postage stamp. Later, she was honored with a 23-cent Great Americans series postage stamp.

- In 1973, Cassatt was added to the National Women's Hall of Fame.

- In 2003, four of her paintings were reproduced on the third issue in the American Treasures stamp series. These were Young Mother (1888), Children Playing on the Beach (1884), On a Balcony (1878/79), and Child in a Straw Hat (circa 1886).

- On May 22, 2009, she was honored by a Google Doodle for her birthday.

- Cassatt's paintings have sold for as much as $4 million. The record price was $4,072,500 in 1996 for In the Box.

- A public garden in Paris is named 'Jardin Mary Cassatt' in her memory.

Gallery

-

The Reader (1877), Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

-

Young Girl at a Window (c. 1883–1884), National Gallery of Art

-

Woman in a Red Bodice and Her Child (c. 1896), Brooklyn Museum

-

Madame Gaillard and Her Daughter Marie-Thérèse (1899), pastel, Reynolda House Museum of American Art

-

Margot in Blue (1903), pastel, Walters Art Museum

-

Young Mother Sewing (1900), oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art

See also

In Spanish: Mary Cassatt para niños

In Spanish: Mary Cassatt para niños

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |