Chinoiserie facts for kids

Chinoiserie (pronounced "sheen-wah-zuh-REE") is a French word meaning "Chinese-style." It describes a European art style that copied and was inspired by Chinese and other East Asian art traditions. This style appeared in many forms, like decorative items, garden designs, buildings, books, plays, and music.

It first became popular in the 17th century. Its popularity grew even more in the 18th century. This was because trade with China and other parts of East Asia increased a lot during that time.

Chinoiserie is similar to the Rococo style, which was also popular then. Both styles are known for being very decorative, often not perfectly balanced (asymmetrical), and focusing on fancy materials. They also often featured nature and scenes of fun and relaxation. Chinoiserie specifically used subjects that Europeans thought were typical of Chinese culture.

Contents

- A Look Back: The History of Chinoiserie

- How Chinoiserie Became Popular

- Persistence After the 18th Century

- Chinese Porcelain: A European Fascination

- Art and Design: Chinoiserie in Painting and Interiors

- Gardens and Architecture: Asian-Inspired Landscapes

- Tea Time: Chinoiserie and a Popular Drink

- Chinoiserie in Fashion

- Chinoiserie in Music

- See also

A Look Back: The History of Chinoiserie

Chinoiserie started showing up in European art and decorations in the mid-to-late 1600s. It became most popular in the mid-1700s, often linked with the Rococo style and artists like François Boucher and Thomas Chippendale. This trend grew because many Chinese and Indian goods arrived in Europe from big trading companies like the English, Dutch, and Swedish East India Companies. Chinoiserie saw another rise in popularity in Europe and the United States from the mid-1800s through the 1920s.

Chinoiserie was a worldwide trend. Local versions developed in India, Japan, Iran, and especially Latin America. For example, Spanish traders brought Chinese items like porcelain and textiles from Manila to markets in Acapulco and Lima. These inspired local artists, like those making Talavera pottery in Puebla.

Interestingly, China also had "occidenterie." This was when Chinese artists made Western-style goods for Chinese buyers in the 1700s. This was not just for the royal court but was available to more people.

How Chinoiserie Became Popular

Chinoiserie gained popularity in Europe in the 18th century due to a fascination with Asia. Increased trade with East Asia gave Europeans more access to new cultures. The "Oriental" style was a source of inspiration. Its rich images and balanced designs seemed to represent an ideal world. This made chinoiserie an important result of cultural exchange. Later, in the 1800s, it became part of a broader trend called exoticism.

Europeans in the 17th and 18th centuries didn't always have a clear picture of China. Terms like 'Orient' or 'Far East' were often used generally for East Asia. The word 'chinoiserie' first appeared in French books in the 1800s. It officially entered the Dictionnaire de l'Académie (French dictionary) in 1878.

Europeans learned about China from travelers like Marco Polo and from merchants. Later, Jesuits provided deeper insights into Chinese culture. While Europeans sometimes had inaccurate ideas, they often respected Chinese art and civilization. However, some critics disliked chinoiserie. They saw it as too whimsical and lacking the logic of classical art.

Persistence After the 18th Century

Chinoiserie continued into the 19th and 20th centuries but became less popular. Interest dropped after King George IV, a big fan, passed away in 1830. The First Opium War (1839–1842) between Britain and China disrupted trade, causing further decline.

As British–Chinese relations improved, chinoiserie saw a small comeback. Prince Albert moved many pieces to Buckingham Palace. Chinoiserie helped remind Britain of its past.

Chinese Porcelain: A European Fascination

From the 1400s to the 1700s, Western designers tried to copy the amazing skill of Chinese export porcelain makers. They had only some success. One early attempt was Medici porcelain, made in Florence in the late 1500s. Later, in 1673, a factory in Rouen, France, started making "soft-paste" porcelain. Europeans especially wanted to copy "hard-paste" porcelain, which was highly valued.

Direct copying of Chinese designs began in pottery called faience in the late 1600s. This moved into European porcelain production, especially for tea sets. This trend reached its peak during the Rococo chinoiserie period (around 1740–1770).

Early signs of chinoiserie appeared in the early 1600s in countries with active trading companies like Holland and England. Dutch pottery, like delftware, copied genuine blue-and-white Ming Dynasty designs. A book by Johan Nieuhof with 150 pictures also helped make chinoiserie popular. Early porcelain factories, like Meissen, naturally imitated Chinese designs.

Art and Design: Chinoiserie in Painting and Interiors

The ideas from East Asian decorative arts and paintings spread into European and American art. Chinese painting influenced European art with its unbalanced designs, cheerful subjects, and a general sense of playfulness.

Chinoiserie in Painting

William Alexander (1767–1816), a British painter, traveled to China in the 1700s. He was directly inspired by the culture and landscapes he saw. He showed an idealized, romantic view of Chinese culture. However, his depictions were also based on common ideas about China. European paintings of China and East Asia often depended on Western ideas, rather than showing the culture as it truly was.

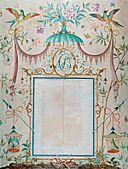

Decorating Homes with Chinoiserie

Many European monarchs, like Louis XV of France, loved chinoiserie. It fit very well with the Rococo style. Entire rooms, such as those at Château de Chantilly, were painted with chinoiserie designs. Palaces in Central Europe, like the Castle of Wörlitz, have Chinese-themed rooms and buildings. "Chinese Villages" were built in parks in Germany, Sweden, and Russia.

Thomas Chippendale, a famous furniture maker, created mahogany tea tables and cabinets with delicate Chinese-inspired patterns. Other furniture also took inspiration from Chinese designs. Chinoiserie items included "japanned" ware (imitating Asian lacquer) and painted tin. Early painted wallpapers also featured chinoiserie designs. Ceramic figures and table decorations were also made in this style.

Europeans started making furniture that looked like Chinese lacquer furniture. It was often decorated with Chinese patterns like pagodas. Chippendale's design book, The Gentleman and Cabinet-maker's Director, helped popularize this. His furniture often had colorful birds, flowers, or imaginary exotic places.

The growing use of wallpaper in European homes in the 1700s also showed interest in chinoiserie. Wealthy Europeans first bought unique, handmade Chinese wallpaper. Later, printed chinoiserie wallpaper became available to more people. These patterns featured pagodas, flowers, and imaginary scenes, matching other decorations in private rooms.

Gardens and Architecture: Asian-Inspired Landscapes

Europeans learned about Chinese and East Asian garden design through a concept called Sharawadgi. This word meant beauty without strict order, like a pleasing irregularity in a garden. Sir William Temple introduced the term in his essay in 1685. European gardeners used sharawadgi to create gardens that reflected the natural, unbalanced look of Eastern gardens.

These gardens often had fragrant plants, decorative rocks, ponds, and winding paths. They were often enclosed by a wall. Buildings in these gardens included pagodas and pavilions.

Gardens like London's Kew Gardens show clear Chinese influence. The huge 163-foot Great Pagoda at Kew, designed by William Chambers, combines English and Chinese styles. A copy of it was built in Munich's Englischer Garten. Some fancy homes, like Badminton House, even had entire guest rooms decorated in the chinoiserie style.

Tea Time: Chinoiserie and a Popular Drink

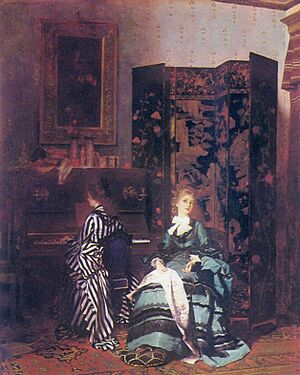

The popularity of tea drinking in the 1700s greatly contributed to chinoiserie's rise. The elegant and home-focused culture of tea drinking needed the right chinoiserie setting. After 1750, England was importing huge amounts of tea annually.

The love for chinoiserie porcelain and tea drinking was often linked to women. Many important women in society were famous collectors of chinoiserie porcelain. These included Queen Mary II and Queen Anne. Their homes were seen as examples of good taste and helped set trends.

Chinoiserie in Fashion

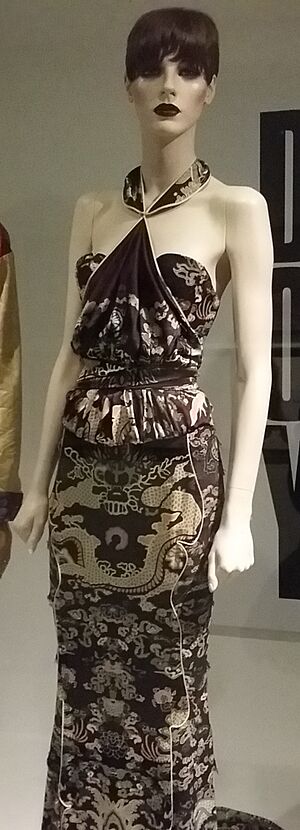

The term chinoiserie is also used in the fashion world. It describes designs in clothes and textiles that are inspired by Chinese styles. Since the 1600s, Chinese art and beauty have inspired artists and designers. This happened when goods from East Asian countries were first widely seen in Western Europe.

In the 1700s and 1800s, chinoiserie fashion was very popular in France. Most Chinese-inspired fashion from this time came from France. Chinoiserie also inspired designers like Mariano Fortuny.

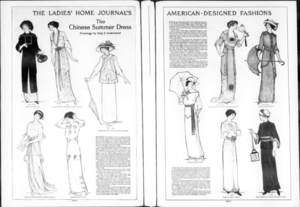

In the early 1900s, European fashion designers looked to China and other non-European places for new ideas. Vogue magazine even said that China had helped inspire global fashion. Chinese patterns became popular in European fashion during this time. Chinese clothing also influenced different styles of comfortable loungewear.

A fashion trend for everyday jackets and coats to be cut in Chinese-inspired styles appeared in the early 1900s. For example, the Ladies' Home Journal in June 1913 showed garments influenced by Chinese court robes, skirts, collars, and traditional Chinese embroidery. The magazine stated that designers looked to China for "unique and new" clothes that would still fit American women's needs.

Chinoiserie in Music

Western music started using ideas from Chinese and East Asian music in the mid-1600s. Examples include operas like Henry Purcell's The Fairy-Queen (1692). Jean-Jacques Rousseau included what he called an authentic Chinese melody in his 1768 Dictionary of Music. This melody was later used by Carl Maria von Weber in his Overtura cinesa (1804). Jacques Offenbach's funny one-act operetta Ba-ta-clan (1855) was a big hit in Paris. The 1889 Paris World Fair also helped bring world music to the attention of Western composers.

In the early 1900s, French composers used a dreamy view of Chinese culture in pieces like Claude Debussy's Pagodas (1903). Three major examples of musical chinoiserie from the 20th century are Gustav Mahler's Das Lied von der Erde (1908), Igor Stravinsky's The Nightingale (1914), and Giacomo Puccini's Turandot (1926).

Other notable pieces include Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's 'Chinese Dance' from The Nutcracker (1892). Albert Ketèlbey's orchestral piece In a Chinese Temple Garden (1923) is another example. Chinese music has also influenced popular music, from musicals like The King and I (1951) to jazz and rock. These often use common Western ideas about Chinese music, like the "oriental riff" with a five-note scale (pentatonic scale).

See also

In Spanish: Chinería para niños

In Spanish: Chinería para niños

- Chinoiserie in fashion

- Japonisme

- Orientalism

- Oriental riff

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |