First Opium War facts for kids

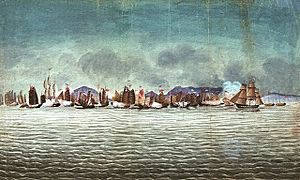

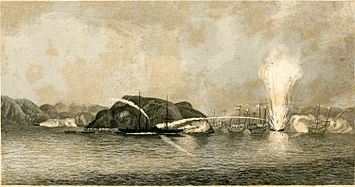

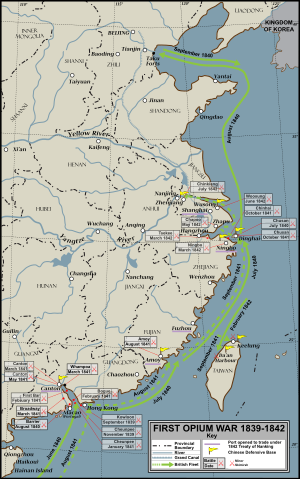

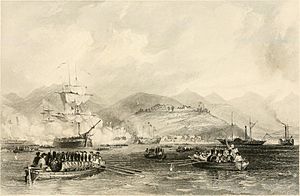

{{Infobox military conflict | conflict = First Opium War | partof = the Opium Wars | image = Destroying Chinese war junks, by E. Duncan (1843).jpg | image_size = 325px | caption = The East India Company steamship Nemesis (right background) destroying war junks during the Second Battle of Chuenpi, 7 January 1841 | date = 4 September 1839 – 29 August 1842

(2 years, 11 months, 3 weeks and 4 days) | place = China and South China Sea | territory = Hong Kong Island ceded to Britain | result = British victory

Establishment of five treaty ports in:

| combatant1 = ![]() United Kingdom

United Kingdom

| combatant2 = ![]() China

China

| commander1 =

Queen Victoria

Queen Victoria Robert Peel

Robert Peel Lord Palmerston

Lord Palmerston Charles Elliot

Charles Elliot George Elliot

George Elliot James Bremer

James Bremer Hugh Gough

Hugh Gough Henry Pottinger

Henry Pottinger William Parker

William Parker Humphrey Senhouse

Humphrey Senhouse

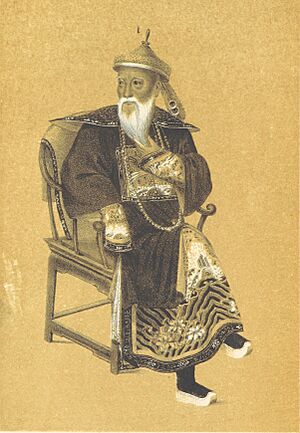

| commander2 = {{plainlist|

Daoguang Emperor

Daoguang Emperor Lin Zexu

Lin Zexu- {{flagdeco|Qishan (official)|Qishan]]

- {{flagdeco|Yishan (official)|Yishan]]

- {{flagdeco|Yijing (prince)|Yijing]]

- {{flagdeco|Yilibu]]

- {{flagdeco|Guan Tianpei]] †

- {{flagdeco|Chen Huacheng]] †

- {{flagdeco|Ge Yunfei]] †

- Template:Country data Yang Fang (general)

Quick facts for kids First Opium War |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 第一次鴉片戰爭 | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

The First Opium War (also called the Anglo-Sino War) was a series of battles. It was fought between Britain and the Qing dynasty of China. The war lasted from 1839 to 1842.

The main reason for the war was China's strict ban on the opium trade. Chinese officials seized large amounts of opium from merchants in Canton. They also threatened to punish future offenders with death. The British government supported its merchants. It demanded payment for the seized goods. Britain also insisted on free trade and equal diplomatic treatment with China. Opium was a very profitable product for Britain in the 1800s.

After months of disagreements, the British navy launched an attack in June 1840. The British forces had better ships and weapons. They defeated the Chinese by August 1842. Britain then forced China to sign the Treaty of Nanking. This treaty made China open up more to foreign trade. It also required China to pay money to Britain. Finally, China had to give Hong Kong to the British. The opium trade continued in China after the war. Many historians see this war as the start of modern Chinese history.

In the 1700s, Europeans wanted many Chinese luxury goods. These included silk, porcelain, and tea. This led to a trade imbalance. Europe bought a lot from China but sold little in return. European silver flowed into China through the Canton System. This system limited foreign trade to the port city of Canton.

To balance this, the British East India Company started growing opium in Bengal. They allowed British merchants to sell opium to Chinese smugglers. This illegal trade reversed China's trade surplus. It caused silver to leave China. This worried Chinese officials greatly.

In 1839, the Daoguang Emperor sent Lin Zexu to Canton. His job was to stop the opium trade completely. Lin wrote a letter to Queen Victoria. He asked her to stop the opium trade. However, the Queen never saw this letter. Lin then used force against the foreign merchants. He arrived in Guangzhou in January and set up coastal defenses. In March, British dealers had to hand over a huge amount of opium. On June 3, Lin ordered the opium to be publicly destroyed on Humen Beach. This showed the government's strong will to ban the trade. Other supplies were also taken, and foreign ships on the Pearl River were blocked.

Tensions grew in July. British sailors killed a Chinese villager. The British government refused to hand over the accused men. Fighting then began. The British navy destroyed the Chinese naval blockade. They launched an attack. The Royal Navy used its powerful ships and guns. They defeated the Chinese Empire many times.

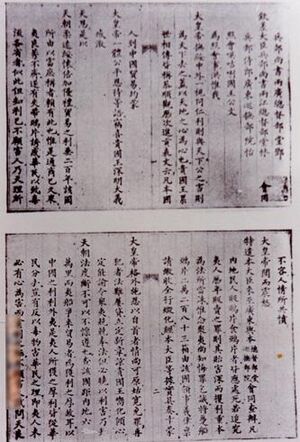

In 1842, the Qing dynasty had to sign the Treaty of Nanking. The Chinese later called this the first of the "unequal treaties". The treaty made China pay money to Britain. It also gave British people special rights in China. Five treaty ports were opened for British merchants. Hong Kong Island was given to the British Empire. The treaty did not fully meet Britain's trade goals. This led to the Second Opium War (1856–60). The social problems that followed also led to the Taiping Rebellion. This further weakened the Qing government.

Contents

How Trade Began

Direct sea trade between Europe and China started in 1557. The Portuguese rented a trading post in Macau from the Ming dynasty. Other European countries soon followed. They joined the existing Asian trade network. They competed with Arab, Chinese, Indian, and Japanese merchants.

Trade between China and Europe grew much faster after 1565. The Manila Galleons brought silver from South American mines into Asia. China was a main destination for this silver. The Chinese government required that Chinese goods be traded only for silver.

British ships started appearing near China's coasts from 1635. Britain did not have formal relations with China. So, British merchants could only trade at specific ports. These were Zhoushan, Xiamen, and Guangzhou. Official British trade was handled by the British East India Company. This company had a special permission from the king to trade with the Far East. The East India Company slowly became the main trader between China and Europe. This was thanks to its position in India and the strength of the Royal Navy.

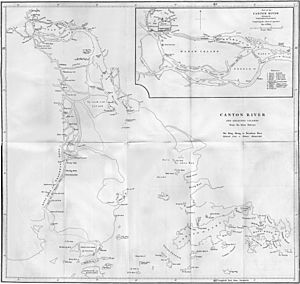

Trade improved after the new Qing dynasty eased sea trade rules in the 1680s. Formosa (Taiwan) came under Qing control in 1683. Guangzhou (Canton) became the preferred port for foreign trade. Other ports could not match Canton's location at the mouth of the Pearl River Delta. Canton also had long experience in managing trade.

From 1700, Canton was the center of sea trade with China. The Qing authorities gradually developed this into the "Canton System". Trading in China was very profitable for both European and Chinese merchants. Goods like tea, porcelain, and silk were highly valued in Europe.

The Qing government strictly controlled the system. Foreign traders could only do business through a group of Chinese merchants called the Cohong. They were not allowed to learn Chinese. Foreigners could only live in the Thirteen Factories. They could not enter or trade in other parts of China. Only low-level government officials could be dealt with. The emperor's court could not be approached, except for official diplomatic visits. These rules were known as the Prevention Barbarian Ordinances.

The Cohong merchants were very powerful. They decided the value of foreign products. They bought or rejected imports. They also sold Chinese exports at a fair price. The Cohong was made up of 6 to 20 merchant families. Many of these families were started by low-ranking officials. European merchants also had to pay customs fees and other charges.

Despite these rules, silk and porcelain remained popular in Europe. There was also a huge demand for Chinese tea in Britain. From the mid-1600s, China received about 28 million kilograms of silver. This silver came mainly from European powers, in exchange for Chinese goods.

Why Trade Became Difficult

For over a century, trade between China and Europe continued. China benefited greatly from this trade. European nations had large trade deficits. This meant they bought more from China than they sold. But the demand for Chinese goods kept the trade going.

Europe also had access to cheap silver from the Americas. This helped their economies stay stable despite the trade deficit. This silver was also sent directly to China. In contrast, Qing China had a trade surplus. Foreign silver flowed into China. This expanded the Chinese economy. However, it also caused inflation and made China rely on European silver.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, European economies grew. This increased their need for precious metals to make new coins. This reduced the silver available for trade in China. It also raised costs and led to competition among merchants. European governments faced a constant trade deficit. They had to risk silver shortages at home to supply their merchants in Asia.

Wars between Great Britain and Spain in the mid-1700s made this worse. These wars disturbed the international silver market. They also led to new independent nations like the United States and Mexico. Without cheap silver from the colonies, European merchants took silver directly from their own economies. This angered governments. They saw their economies shrink. This also led to bad feelings towards China for limiting European trade. The Chinese economy was not affected by silver price changes. China could import Japanese silver to keep its money supply stable. European goods were still not in high demand in China. So, China's trade surplus with Europe continued.

Changes in Trade Rules

The start of the opium trade and new ideas changed how trade worked. In Britain, new economic ideas like classical economics by Adam Smith became popular. These ideas led to a decline in the belief in mercantilism. Under the old system, the Qianlong Emperor limited trade to licensed Chinese merchants. The British government gave a trade monopoly only to the British East India Company.

This system was challenged in the 1800s. The idea of free trade became popular in the West. Britain, powered by the Industrial Revolution, used its growing navy. It wanted to spread a more open economic model. This meant open markets and fewer trade barriers. This policy aimed to open foreign markets to British goods. It also gave the British public more access to goods like tea. Britain adopted the gold standard in 1821. This meant it needed to buy silver and gold from other countries. This further pushed the British government to demand more trading rights in China.

The Qing dynasty, however, kept a strict economic philosophy. It called for strong government control to keep society stable. The Qing government was not against trade. But it did not need many imports. Heavy taxes on luxury goods also limited pressure to open more ports. China's strict merchant system also blocked efforts to open ports. Chinese merchants inland wanted to avoid competition from foreign goods. The Cohong families in Canton made a lot of money by keeping their city the only entry point for foreign products.

Around 1800, countries like Britain, the Netherlands, and the United States wanted more trading rights in China. Their main goal was to end the Canton System. They wanted to open China's huge markets to trade. Britain especially wanted to increase its exports to China.

British attempts to negotiate more access were rejected by Chinese Emperors. These included missions led by Macartney (1793) and Earl William Amherst (1816). In 1816, Amherst refused to perform the traditional kowtow. This was a deep bow that the Qing saw as a sign of respect. The Qing saw this as a serious insult. Amherst and his group were sent away from China. This angered the British government.

A major reason for British dissatisfaction was the trade imbalance. British people loved Chinese tea, porcelain, and silk. But Chinese consumers did not want British goods. This meant Britain had to use a lot of silver to pay for Chinese products. Britain had a huge trade deficit. High tariffs also made the British government unhappy.

Britain also increased its military strength in Southern China. It sent warships to fight pirates on the Pearl River. In 1808, Britain set up a permanent base of troops in Macau. This was to defend against French attacks.

Foreign Merchants in Canton

As the illegal opium trade grew, more foreigners came to Canton and Macau. The Thirteen Factories area in Canton expanded. It became known as the "foreign quarter." Some merchants began to stay in Canton all year. A local business group was formed. By the early 1800s, trade between Europe and China became very profitable. A small group of European merchants gained great power in China. Most of them dealt in legal goods, but they also made a lot of money from selling opium.

Some Western missionaries also arrived. They began to spread Christianity in China. Some officials allowed this. But others clashed with Chinese Christians. This increased tensions between Western merchants and Qing officials.

As the foreign community in Canton grew, China faced internal problems. The White Lotus Rebellion (1796–1804) used up a lot of the Qing dynasty's silver. This forced the government to tax merchants more heavily. These taxes continued even after the rebellion. The Chinese government started a huge project to repair state properties on the Yellow River. Merchants in Canton were also expected to help fight bandits. These taxes greatly reduced the profits of the Cohong merchants. By the 1830s, their wealth had shrunk a lot.

Also, China's own money lost value. Many people in Canton started using foreign silver coins. Spanish coins were the most valued. This allowed people in Canton to make many Chinese coins from melted-down Western coins. This greatly increased the city's wealth and tax income. It also tied much of the city's economy to foreign merchants.

A big change happened in 1834. Reformers in Britain, who supported free trade, succeeded. They ended the British East India Company's monopoly. This meant merchants no longer needed special permission to trade in the Far East. The British China trade was now open to private businesses.

Napier's Mission

In late 1834, Britain sent Lord William John Napier to Macau. He was one of the British superintendents of trade in China. Napier was told to follow Chinese rules. He was also to talk directly with Chinese authorities. He was to oversee the illegal opium trade.

When he arrived, Napier tried to contact the Viceroy of Canton directly. This was against the rules. The Viceroy refused his letter. On September 2, an order was given to temporarily close British trade. In response, Napier ordered two Royal Navy ships to fire on Chinese forts. This showed British strength. But war was avoided because Napier became ill. He ordered a retreat.

The brief fight was criticized by the Chinese government. It also drew criticism from the British government and foreign merchants. Other countries, like the Americans, continued peaceful trade. But the British were told to leave Canton. Lord Napier died a few days later. After his death, Charles Elliot became Superintendent of Trade in 1836. He continued Napier's work to improve relations with the Chinese.

Rising Tensions

In 1839, the Daoguang Emperor appointed Lin Zexu. He was a respected official. His job was to completely stop the opium trade. Lin wrote a famous letter to Queen Victoria. He asked her to consider the moral issues of the opium trade. This letter never reached the Queen.

Lin banned the sale of opium. He demanded that all supplies be given to Chinese authorities. He also closed the Pearl River Channel. This trapped British traders in Canton. Chinese troops seized opium in warehouses and on British ships. They destroyed the opium.

The British Superintendent of Trade, Charles Elliot, protested. He ordered all ships with opium to leave and prepare for battle. Lin responded by surrounding the foreign dealers in Canton. He stopped them from contacting their ships. To ease the situation, Elliot convinced British traders to cooperate. They handed over their opium. Elliot promised them that the British government would pay them back. This promise put a huge financial burden on the British government. This was a key reason for the later British attack. In April and May 1839, British and American dealers surrendered over 20,000 chests of opium. This was publicly destroyed on the beach outside Canton.

After the opium was surrendered, trade restarted. But there was a strict rule: no more opium could be brought into China. Lin wanted to control foreign trade better. He decided to change the existing bond system. Under this system, a foreign captain and a Chinese merchant would swear that no illegal goods were on the ship. Lin found that no violations had been reported in 20 years. He was very angry. So, Lin demanded that all foreign merchants and Chinese officials sign a new bond. This bond promised not to deal in opium, under penalty of death. The British government opposed this. They felt it went against the idea of free trade.

Britain's Response

After China cracked down on the opium trade, Britain discussed how to react. Many trade groups and manufacturers pushed for action. The British government, led by Prime Minister Melbourne, decided on October 1, 1839, to send an expedition to China. War preparations began.

In November 1839, Lord Palmerston, the Foreign Minister, told the Governor General of India to prepare troops. On February 20, 1840, Palmerston wrote two letters. One was to the Elliots, the British officials in China. The other was to the Daoguang Emperor. The letter to the Emperor said that Britain was sending a military force to China.

Palmerston told the British commanders to block the Pearl River. They were to deliver his letter to a Chinese official. Then, they were to capture the Chusan Islands. They also had to block the mouth of the Yangtze River. After that, they would start talks with Chinese officials. Finally, they would sail the fleet into the Bohai Sea and send another copy of the letter to Beijing.

Palmerston also listed what Britain wanted:

- To be treated with respect by Chinese authorities.

- The right for British officials to judge British citizens in China.

- Payment for destroyed British property.

- To get the best trading status with China.

- The right for foreigners to live safely and own property in China.

- To ensure British people carrying illegal goods were not harmed, even if the goods were seized.

- To end the system that limited British merchants to trading only in Canton.

- To open the cities of Canton, Amoy, Shanghai, Ningpo, and northern Formosa to all foreign trade.

- To get islands along the Chinese coast that could be easily defended.

Palmerston left it to Superintendent Elliot to decide how to achieve these goals. He preferred talks but did not trust diplomacy. He wrote that Britain demanded "satisfaction for the past and security for the future." He added that Britain would not trust negotiations. Instead, it sent a military force to achieve its goals.

The War Begins

First Actions

The Chinese navy in Canton was led by Admiral Guan Tianpei. He had fought the British before. The Qing southern army was led by General Yang Fang. The Daoguang Emperor and his court had overall command. The Chinese government first thought the British had been successfully driven away, like in 1834. Few preparations were made for a British attack.

Without a major base in China, the British moved their merchant ships away. But the Royal Navy kept its China squadron near the Pearl River. From London, Palmerston continued to direct operations. He ordered the East India Company to send troops from India. It was decided that the war would be a "punitive expedition," not a full-scale conflict. Superintendent Elliot remained in charge of British interests. Commodore James Bremer led the Royal Marines and the China Squadron. Major General Hugh Gough commanded the British land forces. He was promoted to overall commander. The British government paid for the war. Plans were made to attack Chinese ports and rivers.

British forces began to gather in Singapore by mid-June 1840. They practiced landing on beaches. This prepared them for attacks.

British Attacks Begin

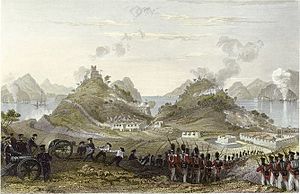

In late June 1840, the first part of the British force arrived in China. It included 15 barracks ships, four steam-powered gunboats, and 25 smaller boats. Commodore Bremer was in command. The British demanded that the Qing government pay for trade losses and destroyed opium. But the Chinese in Canton refused.

Palmerston had told Elliot and Admiral George Elliot to get at least one island for trade. With the British force ready, they attacked the Chusan Archipelago. Zhoushan Island, the largest island, was the main target. Its port, Dinghai, was very important. When the British fleet arrived, Elliot demanded the city surrender. The Chinese commander refused. He asked why the British were bothering Dinghai, since they had been driven from Canton. Fighting began. The Royal Navy destroyed 12 small Chinese junks. British marines captured the hills south of Dinghai.

The British captured the city after heavy shelling on July 5. The Chinese defenders had to retreat. The British took Dinghai harbor. They planned to use it as a base for operations in China. In late 1840, disease spread in the Dinghai garrison. Many British soldiers died from illness.

After taking Dinghai, the British split their forces. One fleet went south to the Pearl River. Another went north to the Yellow Sea. The northern fleet sailed to Peiho. Elliot personally gave Palmerston's letter to Chinese officials there. Qishan, a high-ranking official, replaced Lin as Viceroy. He was chosen to negotiate with the British.

Negotiations began between Qishan and Elliot. After a week, they agreed to move talks to the Pearl River. Qishan promised to pay British merchants for damages. But the war was not over. Both sides continued fighting. In spring 1841, more British troops arrived from India. They prepared for an attack on Canton. A new iron steamship, HMS Nemesis, joined the fleet. The Chinese navy had no answer to this powerful ship.

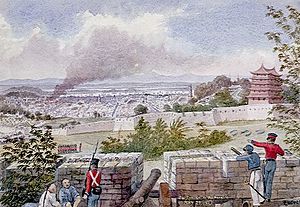

On August 19, three British warships and 380 marines drove the Chinese from the land bridge between Macau and the mainland. This victory and the arrival of the Nemesis boosted pro-British support in Macau. Portugal remained neutral but allowed British ships to dock. With Dinghai and Macau secured, the British focused on the war on the Pearl River. Five months after the British victory at Chusan, the northern fleet sailed south to Humen, known as The Bogue. Bremer believed controlling the Pearl River and Canton would give Britain a strong position. It would also allow trade to restart after the war.

Pearl River Battles

While the British were fighting in the north, Chinese Admiral Guan Tianpei strengthened defenses at Humen. He expected the British to try to reach Canton. The Humen forts blocked the river. They had 3,000 men and 306 cannons. By the time the British fleet was ready, 10,000 Qing soldiers defended Canton. The British fleet arrived in early January. They began firing on the Chinese defenses at Chuenpi.

On January 7, 1841, the British won a big victory in the Second Battle of Chuenpi. They destroyed 11 Chinese junks and captured the Humen forts. This allowed the British to block The Bogue. The Qing navy had to retreat upriver.

Qishan knew how important the Pearl River Delta was to China. He also knew British naval power made it hard to retake the area. So, he tried to stop the war from spreading. On January 21, Qishan and Elliot drafted the Convention of Chuenpi. They hoped this document would end the war. The convention would give Britain and China equal diplomatic rights. It would exchange Hong Kong Island for Chusan. It would also free British citizens held by the Chinese. Trade would reopen in Canton by February 1, 1841. China would also pay six million silver dollars for the opium destroyed in 1838. The legal status of the opium trade was left for later talks.

However, both governments refused to sign the convention. The Daoguang Emperor was furious that Chinese land would be given away without his permission. He ordered Qishan arrested. Lord Palmerston recalled Elliot. He wanted more concessions from China.

The short break in fighting ended in early February. The Chinese refused to reopen Canton to British trade. On February 19, a British boat was fired upon from a fort. This led to a British response. British commanders ordered another blockade of the Pearl River. They restarted fighting. The British captured the remaining Bogue forts on February 26 during the Battle of the Bogue. They also won the Battle of First Bar the next day. This allowed the fleet to move closer to Canton. Admiral Tianpei was killed on February 26.

On March 2, the British destroyed a Qing fort near Pazhou. They captured Whampoa. This directly threatened Canton's east side. Major General Gough, who had just arrived, led the attack on Whampoa. Superintendent Elliot and the Governor-General of Canton declared a 3-day truce on March 3. British forces from Chusan arrived in the Pearl River. The Chinese military also received reinforcements. By March 16, General Yang Fang commanded 30,000 men around Canton.

While the main British fleet prepared to sail to Canton, three warships went to the Xi River estuary. They planned to navigate the waterway between Macau and Canton. This fleet, led by Captain James Scott and Superintendent Elliot, included steamships. These shallow-draft ships could approach Canton from an unexpected direction. In battles from March 13 to 15, the British destroyed Chinese ships, guns, and equipment. Nine junks, six forts, and 105 guns were destroyed or captured in the Broadway expedition.

With the Pearl River clear, the British considered attacking Canton. Elliot believed they should negotiate from their strong position. The Qing army did not attack. Instead, they fortified the city. Chinese engineers built mud defenses. They sank junks to block the river. They also built fire rafts and gunboats. Chinese merchants were told to remove silk and tea from Canton. Locals were forbidden from selling food to British ships. On March 16, a British ship under a flag of truce was fired upon. This led the British to set the fort on fire. These actions convinced Elliot that the Chinese were preparing to fight. After the Broadway expedition ships returned, the British attacked Canton on March 18. They took the Thirteen Factories with few losses. Trade reopened after talks with the Cohong merchants. After more military successes, British forces held the high ground around Canton. Another truce was declared on March 20. Elliot withdrew most Royal Navy warships downriver.

In mid-April, Yishan (Qishan's replacement) arrived in Canton. He was the Daoguang Emperor's cousin. He said trade should stay open. He sent messengers to Elliot. He also began gathering troops outside Canton. The Qing army outside the city soon reached 50,000 men. Money from reopened trade was used to repair Canton's defenses. Hidden artillery batteries were built. Chinese soldiers were sent to Whampoa and the Bocca Tigris. Hundreds of small river boats were armed. The Daoguang Emperor ordered his forces to "Exterminate the rebels." He wanted the British driven from the Pearl River. Then, Hong Kong would be retaken. This order was leaked. Foreign merchants in Canton became suspicious. In May, many Cohong merchants and their families left the city. Rumors spread that Chinese divers would drill holes in British ships. Fire rafts were also being prepared.

The Qing army was weakened by internal conflicts. Yishan did not trust Cantonese civilians or soldiers. He relied on forces from other provinces. On May 20, Yishan said the people of Canton should not be afraid of the gathering troops. The next day, Elliot asked all British merchants to leave the city. Warships were called back to Canton.

On the night of May 21, the Qing launched a surprise attack. Hidden artillery batteries opened fire. Qing soldiers retook the British Factory. A large group of 200 fire rafts was sent towards British ships. Fishing boats with guns also attacked. The British ships avoided the attack. Stray rafts set Canton's waterfront on fire. This lit up the river and ruined the night attack. Downriver, the Chinese attacked British ships at Whampoa. Major General Gough gathered British forces at Hong Kong. He ordered a quick advance upriver to Canton. These reinforcements arrived on May 25. The British counter-attacked. They took the last four Qing forts above Canton. They also shelled the city.

The Qing army fled in panic. The British chased them. On May 29, about 20,000 villagers attacked and defeated 60 Indian soldiers. This was known as the Sanyuanli Incident. Gough ordered a retreat back to the river. Fighting stopped on May 30, 1841. Canton was fully occupied by the British. The British command and the governor-general of Canton agreed to a ceasefire. Under this peace, the British were paid to withdraw beyond the Bogue forts. They completed this by May 31. Elliot signed the treaty without consulting the British army or navy. This displeased General Gough.

Yishan declared the defense of Canton a diplomatic success. He told the Emperor that the "barbarians" had begged for mercy. He said they would withdraw their ships if their debts were paid and trade allowed. However, General Yang Fang was criticized by the Emperor for agreeing to a truce. The Emperor was not told that the British force was still strong. The imperial court continued to debate the war. The Daoguang Emperor wanted Hong Kong retaken.

Fighting in Central China

After leaving Canton, the British moved their forces to Hong Kong. British leaders debated how to continue the war. Elliot wanted to stop fighting and reopen trade. Major General Gough wanted to capture Amoy and block the Yangtze River. In July, a typhoon hit Hong Kong. It damaged British ships and facilities.

The situation changed on July 29. Elliot learned he had been replaced by Henry Pottinger. Pottinger arrived in Hong Kong on August 10. He wanted to negotiate a treaty for all of China, not just the Pearl River. He turned away Chinese messengers from Canton. He allowed the British forces to continue their war plans. Admiral Sir William Parker also arrived. He replaced Humphrey Fleming Senhouse (who died of fever) as naval commander. The British commanders agreed to move fighting north. This would put pressure on Beijing. On August 21, the fleet sailed for Amoy.

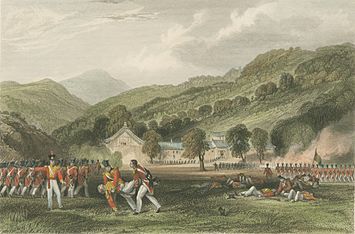

On August 25, the British fleet entered the Jiulong River estuary and arrived at Amoy. The city was ready for a naval attack. Chinese engineers had built artillery batteries into the granite cliffs. Parker thought a naval attack alone was too risky. So, Gough ordered a combined naval and ground attack. On August 26, British marines and infantry attacked the Chinese defenses. The Royal Navy provided covering fire. Several large British ships could not destroy the biggest Chinese battery. So, British infantry climbed and captured the position.

The city of Amoy was abandoned on August 27. British soldiers entered the inner town. They blew up the citadel's powder magazine. They captured 26 Chinese junks and 128 cannons. The captured guns were thrown into the river. Lord Palmerston wanted Amoy to become an international trade port. So, Gough ordered no looting. He had officers enforce the death penalty for plunderers. However, many Chinese merchants refused British protection. They feared being called traitors. The British withdrew to an island on the river. They set up a small base and blocked the Jiulong River. With the city empty, peasants, criminals, and deserters looted it. The Qing army retook the city and restored order days later. The city governor then claimed a victory.

In Britain, changes in Parliament happened. Lord Palmerston was removed as Foreign Minister on August 30. William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne replaced him. Lamb supported the war but wanted a more careful approach.

In September 1841, the British ship Nerbudda was shipwrecked off Taiwan. This was after a brief fight with a Chinese fort. The brig Ann was also lost in March 1842. Survivors from both ships were captured. They were marched to southern Taiwan and imprisoned. On August 10, 1842, 197 were executed by Qing authorities. Another 87 died from bad treatment. This event became known as the Nerbudda incident.

In October 1841, the British strengthened their control over the central Chinese coast. Chusan had been exchanged for Hong Kong in January 1841. The Qing had then re-garrisoned the island. Fearing China would improve its defenses, the British attacked on October 1. The Second Capture of Chusan followed. British forces killed 1500 Qing soldiers and captured Chusan. This victory gave Britain control of Dinghai's important harbor again.

On October 10, a British naval force attacked and captured a fort near Ningbo in central China. A battle broke out between the British army and 1500 Chinese soldiers. This was on the road between Chinhai and Ningbo. The Chinese were defeated. After this loss, Chinese authorities left Ningbo. The British took the empty city on October 13. An imperial cannon factory in the city was captured. This reduced China's ability to replace lost equipment. The fall of Ningbo also threatened the nearby Qiantang River.

The capture of Ningbo made the British command rethink their policy on captured Chinese land. Admiral Parker and Superintendent Pottinger wanted a percentage of all captured Chinese property. General Gough argued this would turn the Chinese people against the British. He said if property had to be taken, it should be public, not private. British policy eventually decided that 10% of all captured property would be taken as war loot. This was in response to injustices against British merchants. Gough later said this would make his men "punish one set of robbers for the benefit of another."

Fighting stopped for the winter of 1841. The British resupplied. Yishan sent false reports to the Emperor in Beijing. He downplayed the British threat. In late 1841, the Daoguang Emperor found out his officials in Canton and Amoy had been sending him exaggerated reports. He ordered the governor of Guangxi to send him accurate accounts. He warned that he would check the information. Yishan was recalled to the capital and faced trial. He was removed from command. Now aware of the serious British threat, Chinese towns began to fortify against naval attacks.

In spring 1842, the Daoguang Emperor ordered his cousin Yijing to retake Ningpo. In the Battle of Ningpo on March 10, the British garrison fought off the attack. They used rifle fire and naval artillery. The British lured the Qing army into the city streets. Then they opened fire, causing many Chinese casualties. The British chased the retreating Chinese army. They captured the nearby city of Cixi on March 15.

The important harbor of Zhapu was captured on May 18 in the Battle of Chapu. A British fleet shelled the town, forcing it to surrender. A group of 300 soldiers fought bravely for several hours. Gough praised their heroism.

Yangtze River Campaign

Many Chinese ports were now blocked or occupied by the British. Major General Gough wanted to hurt the Qing Empire's finances. He planned to attack up the Yangtze River. 25 warships and 10,000 men gathered at Ningpo and Zhapu in May. They planned to move into China's interior.

The expedition's lead ships sailed up the Yangtze. They captured the emperor's tax barges. This was a huge blow. It cut the imperial court's income to a fraction of what it had been.

On June 14, the mouth of the Huangpu River was captured by the British fleet. On June 16, the Battle of Woosung happened. After this, the British captured the towns of Wusong and Baoshan. The undefended outskirts of Shanghai were occupied by the British on June 19. After the battle, Shanghai was looted by retreating Qing soldiers, British soldiers, and local people. Qing Admiral Chen Huacheng was killed defending a fort in Woosong.

The fall of Shanghai left the vital city of Nanjing (Jiangning) open to attack. The Qing gathered an army of 56,000 soldiers to defend Liangjiang Province. They strengthened their river defenses on the Yangtze. However, British naval activity in Northern China led to troops being moved to defend against a feared attack on Beijing. The Qing commander in Liangjiang Province released 16 British prisoners. He hoped for a ceasefire. But poor communication led both sides to reject peace offers. Secretly, the Daoguang Emperor thought about signing a peace treaty. But it was only for the Yangtze River, not the whole war. If signed, the British would have been paid not to enter the Yangtze River.

On July 14, the British fleet on the Yangtze began to sail upriver. Gough learned how important the city of Zhenjiang (Chinkiang) was. Plans were made to capture it. Most of the city's guns had been moved to Wusong and captured by the British. The Qing commanders in the city were disorganized. The British fleet arrived on July 21. The Chinese forts defending the city were destroyed. The Chinese defenders first retreated into the hills. Fighting began when thousands of Chinese soldiers came out of the city. This started the Battle of Zhenjiang.

British engineers blew open the western gate. They stormed into the city. Fierce street-to-street fighting followed. Zhenjiang was devastated. The British suffered their highest combat losses of the war (36 killed) taking the city.

After capturing Zhenjiang, the British fleet cut the vital Grand Canal. This stopped the Caoyun system. It severely disrupted China's ability to move grain across the Empire. The British left Zhenjiang on August 3. They planned to sail to Nanking. They arrived outside Jiangning District on August 9. They were ready to attack the city by August 11. Although the emperor had not yet given clear permission to negotiate, Qing officials in the city agreed to a British request for talks.

The Treaty of Nanking

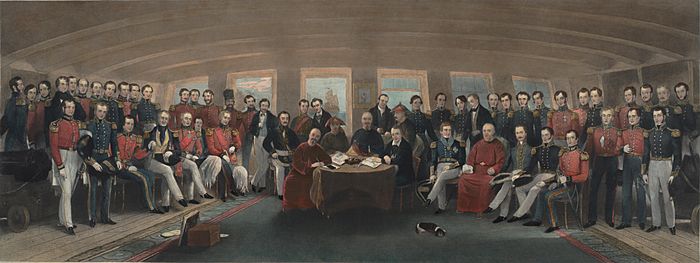

On August 14, a Chinese group led by Qiying and Llipu left Nanking for the British fleet. Talks lasted several weeks. The British insisted the treaty be accepted by the Daoguang Emperor. The court advised the emperor to accept the treaty. On August 21, the Daoguang Emperor allowed his diplomats to sign the peace treaty. The First Opium War officially ended on August 29, 1842. The Treaty of Nanking was signed aboard HMS Cornwallis.

Military Technology and Tactics

British Military Strengths

Britain's military success came from the strength of the Royal Navy. British warships had more guns than Chinese ships. They were also more agile. This allowed them to avoid Chinese boarding attempts. Steamships like HMS Nemesis could move against winds and tides. They had heavy guns and Congreve rockets. Some larger British warships carried more guns than entire Chinese junk fleets. British naval power allowed them to attack Chinese forts with little risk. British naval cannons could fire farther than most Qing artillery.

British soldiers in China used Brunswick rifles and rifle-modified Brown Bess muskets. These could hit targets 200–300 meters away. British marines had percussion caps. These greatly reduced gun misfires. They also allowed firearms to be used in wet conditions. British gunpowder was better made. It had more sulfur than the Chinese mix. This gave British weapons better range, accuracy, and bullet speed. British artillery was lighter and easier to move than Chinese cannons. British guns also had a longer range than Chinese cannons.

British tactics were based on those from the Napoleonic Wars. Many British soldiers were veterans of colonial wars in India. They had experience fighting larger but less advanced armies. In battle, British line infantry would advance in columns. They would form lines when close enough to fire. Companies would fire many shots into the enemy until they retreated. If a position needed to be taken, a charge with bayonets would be ordered. Light infantry companies protected the main lines. They used skirmishing tactics to disrupt the enemy. British artillery destroyed Qing artillery and broke up enemy groups. British weapons had better range, firing speed, and accuracy. This allowed them to damage the enemy before the Chinese could fire back. Naval artillery supported infantry attacks. This helped the British take cities and forts with few losses.

The overall British strategy was to hurt the Qing Empire's finances. The ultimate goal was to gain a colony on the Chinese coast. They did this by capturing Chinese cities and blocking major rivers. After taking a fort or city, the British would destroy its weapons. They would then move to the next target, leaving a small group of soldiers behind. This strategy was planned by Major General Gough. He had little input from the British government after Elliot was recalled. Many private British merchants and East India Company ships in Singapore and India ensured British forces were well supplied.

Qing Dynasty Military Weaknesses

China did not have a single, unified navy. Each province managed its own naval defenses. The Qing had invested in naval defenses earlier. But after the death of the Qianlong Emperor in 1799, the navy declined. More attention went to putting down rebellions. These conflicts left the Qing treasury empty. The remaining naval forces were spread thin, understaffed, underfunded, and uncoordinated.

From the start, the Chinese navy was at a big disadvantage. Chinese war junks were meant for fighting pirates or similar ships. They were better for close-range river battles. Chinese ships were slow. Qing captains often found themselves facing much faster British ships. This meant Chinese ships could only use their front guns. British ships were too big for traditional boarding tactics. Junks also carried fewer and weaker weapons. Chinese ships had poor armor. In several battles, British shells and rockets went through Chinese magazines. This caused gunpowder to explode. Fast steamships like HMS Nemesis could destroy small fleets of junks. The junks had little chance of catching the faster British steamers. The only Western-style warship in the Qing Navy was destroyed in battle.

The Chinese emperor knew about this. In an 1842 order, he said: "The rebellious barbarians... depended upon their strong ships and effective guns to commit outrageous acts... largely because the native war junks are too small to match them. For this reason I... repeatedly ordered our generals to resist on land and not to fight on seas..." He noted that Chinese junks could not go out to sea to fight.

China relied heavily on a large network of forts. The Kangxi Emperor (1654–1722) began building river defenses against pirates. He encouraged using Western-style cannons. By the First Opium War, many forts defended major Chinese cities and waterways. These forts were well-armed and placed strategically. But the Qing defeat showed major flaws in their design.

The cannons in Qing forts were a mix of Chinese, Portuguese, Spanish, and British guns. Chinese-made cannons were poorly made. This limited their effectiveness. Chinese gunpowder had more charcoal than the British mix. This made it more stable for storage. But it also reduced its power as a propellant. This meant shorter range and less accuracy. Overall, Chinese cannon technology was about 200 years behind Britain's.

Chinese forts could not withstand European weapons. They were not designed with sloped defenses. Many did not have protected ammunition storage. The limited range of Qing cannons allowed the British to shell them from a safe distance. Then, they could land soldiers to storm the forts with little risk. Many larger Chinese guns were fixed in place. They could not be moved to fire at British ships. The failure of Qing forts and China's underestimation of the Royal Navy allowed the British to push up major rivers. This disrupted Chinese supplies. For example, the strong forts at Humen were well-placed to stop invaders. But it was not expected that an enemy would attack and destroy the forts themselves, as the British did.

At the start of the war, the Qing army had over 200,000 soldiers. About 800,000 men could be called for war. These forces included Manchu Bannermen, the Green Standard Army, local militias, and imperial garrisons. Qing armies used matchlocks and shotguns. These had an effective range of 100 meters. Chinese soldiers also used traditional weapons. These included long lances, swords, bows and arrows, and rattan shields. Only about 30-40% of their weapons were gunpowder weapons. These included matchlock muskets, heavy muskets, cannons, and fire arrows. Chinese soldiers also had halberds, spears, and crossbows. The Qing dynasty also used many artillery batteries in battle.

Qing tactics were similar to those from earlier centuries. Soldiers with firearms would form lines and fire at the enemy. Men with spears and pikes would push the enemy off the battlefield. Cavalry broke infantry formations and chased retreating enemies. Qing artillery scattered enemy groups and destroyed forts. During the First Opium War, these tactics could not handle British firepower. Chinese melee formations were destroyed by artillery. Chinese soldiers with matchlocks could not effectively fight British lines, who had much longer range. Most battles were in cities, on cliffs, or riverbanks. This limited the Qing's use of cavalry. Many Qing cannons were destroyed by British counter-fire. British light infantry often outflanked and captured Chinese artillery. A British officer said Chinese soldiers were strong and brave. But they were not well-led or used to European warfare.

The Qing dynasty's strategy was to stop the British from taking Chinese land. This defensive strategy failed because the Qing greatly underestimated the British military. Qing defenses on the Pearl and Yangtze rivers could not stop the British push inland. Superior naval artillery prevented the Chinese from retaking cities. The Qing government was slow to react to British attacks. Officials often sent false or incomplete information to their superiors. The Qing military system made it hard to move troops quickly against the mobile British forces. Also, an ongoing conflict with Sikhs on the border with India took away some of the most experienced Qing units.

What Happened Next

The war ended with China signing its first Unequal Treaty, the Treaty of Nanking. In a follow-up agreement, the Treaty of the Bogue, the Qing empire also recognized Britain as an equal. It gave British citizens special privileges in treaty ports. In 1844, the United States and France signed similar treaties with China. These were the Treaty of Wanghia and Treaty of Whampoa.

Could the War Have Been Avoided?

Historians often wonder if the war could have been avoided. One reason it might have been hard to avoid was China's refusal to have regular diplomatic relations with Britain. This was seen when the Macartney mission was rejected in 1793. Because of this, there were no easy ways to talk and solve problems.

Some historians believe the war was unavoidable due to Britain's growing economy and desire for more trade. However, others argue that the British politicians who wanted war were a minority. They needed allies, like Lord Palmerston, to get their war. The British government faced many problems at home and abroad. Foreign Minister Palmerston helped start an "easy war" to solve these political issues. Some argue that the war was not mainly about economics. Instead, it was about upholding Britain's national honor after Chinese insults.

See also

In Spanish: Primera Guerra del Opio para niños

In Spanish: Primera Guerra del Opio para niños

- Illustrated Treatise on the Maritime Kingdoms

- Second Opium War

- Tea in the United Kingdom History – 18th century

- History of tea#United Kingdom

Important People

- Lin Zexu

- William Jardine (merchant)

- William Napier, 9th Lord Napier

- David Sassoon

Other Wars at the Time

- Sino-Sikh War (1841–1842)

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |