Macartney Embassy facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Macartney Embassy |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 馬加爾尼使團 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 马加尔尼使团 | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

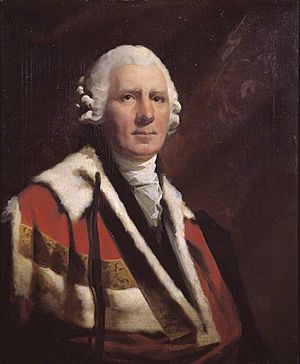

The Macartney Embassy was the first time Britain sent a special group of people to China to talk with its emperor. This happened in 1793. The mission was led by George Macartney, who was Britain's first official representative to China.

The British had several goals. They wanted to open more ports for trade in China. They also hoped to set up a permanent British office in Beijing. Another goal was to get a small island on China's coast for British use. Finally, they wanted fewer rules for British traders in Guangzhou (also called Canton). Macartney's group met with the Qianlong Emperor, but he said no to all their requests. Even though the mission didn't reach its main goals, it was important because the people on it wrote down many interesting things about China's culture, politics, and geography. These notes were brought back to Europe. Later, it was found that a powerful official named Heshen made things difficult for the mission.

Contents

Why the Mission Happened

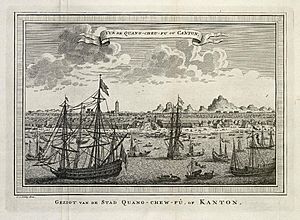

At that time, China had strict rules for foreign trade. This was called the Canton System. It meant that most trade had to go through a group of Chinese companies called the Cohong in Guangzhou. By the 1700s, Guangzhou was the busiest port for trade with China.

In 1757, the Qianlong Emperor decided that all foreign sea trade had to happen only in Guangzhou. He was worried that too much foreign contact might change Chinese society. For example, Chinese people were not allowed to teach their language to foreigners. Also, European traders could not bring women into China.

By the late 1700s, British traders felt limited by these rules. They wanted more trading rights. So, they asked their government to send a special group to the emperor. This was partly because Britain bought a lot of tea from China. They also bought porcelain and silk. The British had to pay for these Chinese goods with silver. This meant Britain was sending a lot of silver to China. They wanted to find British products to sell to the Chinese to balance this trade.

In 1787, Britain tried to send an ambassador, Colonel Charles Cathcart, to China. But he got sick and died before reaching China. After this, Macartney suggested his friend Sir George Staunton lead another mission. But the government decided Macartney himself should go. Macartney agreed, but only if he was made an important noble (an earl) and could choose his team.

Getting Ready for the Trip

Macartney chose George Staunton as his main helper. Staunton brought his son, Thomas, who was a young assistant. John Barrow managed the mission's money. Two doctors, two secretaries, and a military guard also joined. Artists William Alexander and Thomas Hickey came to draw and paint what they saw. A group of scientists, led by James Dinwiddie, also joined the trip.

It was hard to find anyone in Britain who could speak Chinese. This was because it was against the law for Chinese people to teach their language to foreigners. Chinese people who taught foreigners could even be put to death. Macartney didn't want to use local interpreters in China. So, the mission brought four Chinese Catholic priests to help with translation. Two were from Italy, and two wanted to return home to China. The whole group had about 100 people, including scholars and assistants.

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, a famous scientist, also wanted this mission to happen. He was interested in plants and wanted to collect new ones from China. He especially wanted to grow tea plants in India to reduce Britain's need to buy tea from China with silver. He made sure gardeners and artists were part of the trip to study and draw plants.

Henry Dundas, a government official, gave Macartney his official instructions. He noted that Britain traded more with China than any other European country. But Britain had no direct contact with the emperor. Macartney was told to ask for changes to the Canton System. This would allow British traders to use more ports and markets. He also needed to get a small island on the Chinese coast for British traders to use under British law. Another goal was to set up a permanent British office in Beijing. This would create a direct way for the two governments to talk. Finally, Macartney was to learn as much as possible about the Chinese government and society.

Dundas also told Macartney to try to set up trade with other countries in the East, like Japan.

The East India Company, which controlled British trade in the East, had to pay for the mission. They were worried it might hurt their business or make relations worse. But the government believed sending a direct representative of the British king would get more attention than just a trading company.

The embassy also brought many gifts to show off British science and technology. These included clocks, telescopes, weapons, and textiles. Macartney wanted these gifts to show Britain's cleverness and interest in exploring the world.

Journey to China

The group left Portsmouth on September 26, 1792, on three ships. The main warship was HMS Lion. The Hindostan belonged to the East India Company. A smaller ship, the Jackall, also came along. A storm hit them early on, and the Jackall went missing. Luckily, the gifts for the emperor were on the Lion and Hindostan. Young Thomas Staunton used the journey to study Chinese with the interpreters.

They stopped at several places like Madeira, the Canary Islands, and Cape Verde. They waited for the Jackall but then continued. The crew thought the Jackall was lost, but it actually survived and met them later. Macartney bought another ship, the Clarence, to replace it. Strong winds forced them to sail west to Rio de Janeiro, where they arrived in late November. Macartney became ill for a month. While he recovered, he read many books about China.

They left Rio de Janeiro on December 17, sailing east around the Cape of Good Hope. They passed Java in February and reached Jakarta (then called Batavia) on March 6. There, the Jackall rejoined them! The full group sailed to Macau, arriving on June 19, 1793. Some of the Chinese interpreters left the mission here. Macartney wanted to sail directly to Tianjin, a port closer to Beijing, instead of going through Guangzhou. This was a new route for Europeans.

Arriving in China

British officials asked the governor of Guangdong for permission to land at Tianjin. The governor first said no. It was unusual for a visiting mission to choose its own port. But the British explained that their ships carried many large, valuable items that could be damaged if moved overland. The governor also noted that the embassy had traveled a very long way. Sending them back to Guangzhou would cause a big delay. The Qianlong Emperor agreed to the request. He told his officials to treat the British embassy with great politeness.

The embassy left Macao on June 23. They stopped in Zhoushan, where officials helped them find pilots to guide their ships. Chinese officials were surprised by how big and fast the British ships were. They realized these large ships couldn't sail far upriver past Tianjin. So, they arranged smaller boats to carry the mission and its cargo to the capital.

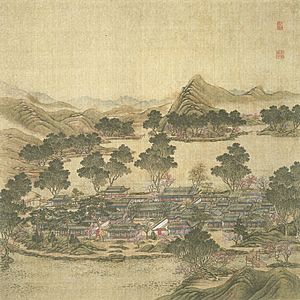

The mission arrived at the mouth of the Hai River on July 25. The water was too muddy for the big ships. The gifts were unloaded onto Chinese boats called junks and taken upstream to Dagu. From there, they were moved to even smaller boats to Tongzhou, which was the end of the Grand Canal. Macartney and his group continued on the smallest British ships. On August 6, Macartney met with Liang Kentang, a high-ranking official. Liang agreed to let the Lion and Hindostan return to Zhoushan. He also told Macartney that the meeting with the emperor would be at the Chengde Mountain Resort in Rehe, not in Beijing as the British expected.

The embassy reached Tianjin on August 11. Macartney and Staunton attended a dinner. A Manchu official named Zhengrui said all gifts must be taken to Rehe and placed before the emperor. But Macartney convinced him to leave some gifts in Beijing to protect them. The emperor's court told Liang not to go with Macartney to Beijing. They didn't want the British to feel too important. Zhengrui became the main contact for the mission. The mission continued up the Hai River on small boats pulled by men. They landed at Tongzhou on August 16.

In Beijing

The embassy arrived in Beijing on August 21. They were taken to a residence near the Old Summer Palace. The British were not allowed to leave this place. Macartney wanted to be closer to the city center. He got permission to move to another residence in Beijing. In Beijing, Zhengrui and two other officials, Jin Jian and Yiling'a, were in charge of the embassy. The gifts were stored in the throne room at the Old Summer Palace. Macartney was the first Briton to visit this palace. John Barrow and James Dinwiddie put together the gifts. The most important gift, a model of the solar system, was so complex it took 18 days to build.

On August 24, Zhengrui brought Macartney a letter from Captain Gower, who said the ships had reached Zhoushan. Macartney wrote back, telling Gower to go to Guangzhou. But Zhengrui secretly sent Macartney's letter to the emperor instead of to Gower. Some men on the Lion had died from illness. The ships had stopped in Zhoushan to recover. The emperor heard about the illness and told officials to keep the British ships quarantined.

The court was upset with Zhengrui for sending Macartney's letter to the emperor. An order from Heshen, a very powerful and corrupt official, said Zhengrui could not make reports alone. He had to get other officials' signatures. Heshen is now known as one of the most corrupt officials in Chinese history. Later, the new emperor, Jiaqing, discovered how corrupt Heshen was and removed him from power. Heshen had insisted that the British pay for tea in silver. This caused problems for trade for the next 50 years. The emperor's order called Zhengrui "ridiculous" and told him to send Macartney's letter to the British ships so they could leave Zhoushan.

On August 26, all members of the embassy, except Barrow and Dinwiddie, moved to their new place in central Beijing.

Crossing the Great Wall

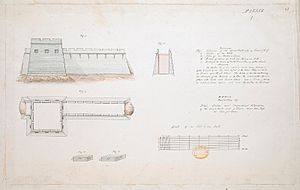

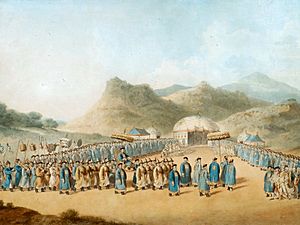

On September 2, about 70 members of the mission, including 40 soldiers, left Beijing. They headed north to Jehol, where the Qianlong Emperor was waiting. They traveled on a special road used only by the emperor. They stopped each night at lodges prepared for the emperor. Guard posts were every five miles. Macartney saw many troops fixing the road for the emperor's return to Beijing.

The group crossed the Great Wall of China at Gubeikou. They were greeted with ceremonial gunfire and many soldiers. William Alexander, who stayed in Beijing, wished he could have seen the Wall. Macartney ordered Lieutenant Henry William Parish to map the Great Wall's defenses. This helped the mission gather information, but it also made the Chinese hosts suspicious. Some of the British men even took bricks from the Wall as souvenirs. After the Great Wall, the land became more mountainous. This made it harder for their horses to travel. The group arrived near Chengde on September 8.

Meeting the Qianlong Emperor

The Qing emperors often went on a special hunting trip north of the Great Wall each autumn. A city was built near the hunting grounds at Chengde for the emperor and his group. Qing emperors often met foreign visitors here. Macartney's embassy was to meet Qianlong here for the emperor's birthday.

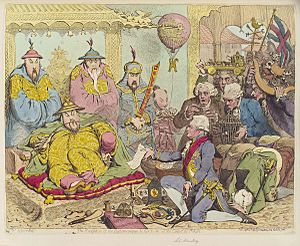

The Kowtow Problem

Even before Macartney left Britain, he and Dundas knew there might be disagreements about the ceremonies. Dundas told Macartney to accept any court rituals that didn't dishonor his king or himself. He said not to let small details get in the way. The kowtow was a big problem. This ritual required a person to kneel on both knees and bow until their forehead touched the ground. It was required when meeting the emperor and when receiving his orders. Portuguese and Dutch traders had done the kowtow. But British people thought it was like being a slave and humiliating. They usually avoided it by leaving the room when imperial orders were read.

Macartney believed that Britain was now the most powerful nation. As a diplomat, he wanted the ceremony to show that the British King George III and Emperor Qianlong were equals. He would only show Qianlong the same respect he would show his own king. He thought the kowtow was too much. Chinese officials kept telling Macartney to perform the kowtow. Heshen even said Macartney would look like a "boor" if he didn't do it. Officials also told Macartney privately that the kowtow was just a "meaningless ceremony."

Macartney offered a solution: he would perform a ceremony, but a Chinese official of equal rank would do the same before a portrait of King George III. He felt it was wrong for Britain to go through the same rituals as China's smaller neighboring countries.

Zhengrui disagreed. He said that the Chinese emperor was seen as the "Son of Heaven" and had no equal. The Chinese viewed the British embassy as a "tribute" mission, like any other. Macartney and Staunton insisted their items were "gifts," but Chinese officials called them "tribute." Macartney himself was seen as just someone bringing tribute, not a representative of a powerful king.

Qianlong offered a compromise on September 8. Macartney could do one prostration instead of the usual nine. But Staunton still presented Macartney's original idea to Heshen. With no agreement and the ceremony days away, Qianlong became impatient. He even thought about canceling the meeting. Finally, they agreed that Macartney would genuflect (bend one knee) before the emperor, just as he would before his own king. He would do this in addition to the single prostration.

The Ceremony

The meeting with the Qianlong Emperor happened on September 14. The British group left their residence at 3 AM and arrived at the emperor's camp at 4 AM. Macartney was with his servants, musicians, and other representatives. The ceremony was held in a large yellow tent. The emperor's throne was in the middle on a raised platform. Thousands of people were there, including visitors from other countries. Viceroy Liang Kentang and the emperor's son were also present.

The emperor arrived at 7 AM. Macartney entered the tent with George and Thomas Staunton and their Chinese interpreter. The others waited outside. Macartney went up to the platform first. He knelt once, exchanged gifts with Qianlong, and gave him King George III's letter. This letter had been translated into Chinese by European missionaries. They made the letter sound more respectful to the emperor. George Staunton followed, and then Thomas Staunton. Since Thomas had studied Chinese, the emperor asked him to say a few words. Thomas later wrote that he thanked the emperor for the gifts. After the British, other visitors presented themselves. A big dinner was held to end the day. The British were seated in the most honored spot, on the emperor's left.

What Happened Next

The Qianlong Emperor later sent a letter to King George III. He explained why he said no to Macartney's requests. These requests included fewer trade rules, an island for British traders, and a permanent British office in Beijing. Qianlong's letter said that China had everything it needed and didn't need to import foreign goods. He also called all Europeans "barbarians." He believed all nations were below China. His letter ended by telling King George III to "Tremblingly obey and show no negligence!" This was a standard way to address Chinese subjects.

Even though the mission failed in its main goals, both the British and Chinese felt they had handled things well. The failure was not just because Macartney didn't kowtow. It was more about two very different ways of seeing the world. The Chinese believed China was the "central kingdom" and superior. The British were expanding their power around the world.

Qianlong also said he could have taken away Britain's existing trade rights because of the king's behavior. But he wouldn't, because he felt sympathy for England, which he saw as far away and unaware of China's great civilization. This made the king and the public in England angry.

Critics in England said the embassy failed because it "acknowledged the inferiority of its country." Macartney himself was made fun of. Later, Macartney became more negative about China. He said China's power was an illusion and that it would eventually fall apart. This prediction did not come true in his lifetime.

The Macartney Embassy is important for many reasons, especially when we look back. It showed a missed chance for both sides to truly understand each other's cultures and goals. It also hinted at how Britain would put more and more pressure on China later on. The lack of understanding between them continued to cause problems for the Qing dynasty as it faced more foreign pressure and internal unrest in the 1800s.

Even though the Macartney Embassy didn't get any special deals from China, it was a success because it brought back detailed notes about a great empire. The artist William Alexander published many drawings based on his paintings. Sir George Staunton wrote the official report of the trip. This detailed work used notes from Lord Macartney and Sir Erasmus Gower, who commanded the expedition. Sir Joseph Banks helped choose the illustrations for this official record.

Members of the Embassy

The Macartney Embassy had about a hundred people, including:

- George Macartney, 1st Earl Macartney (Leader)

- Sir George Staunton, 1st Baronet (Second-in-command), with his 12-year-old son Sir George Staunton, 2nd Baronet

- Sir John Barrow, 1st Baronet (Manager)

- Doctors: Hugh Gillan, William Scott

- Artists: William Alexander, Thomas Hickey

- Scientist: James Dinwiddie

- Gardeners: David Stronach, John Haxton

- Commander: Erasmus Gower, captain of HMS Lion

- Lieutenant John Crewe

- Lieutenant Henry William Parish (Royal Artillery officer and draftsman)

- Lieutenant-Colonel George Benson (Leader of the Ambassador's Guard)

- Interpreters: Paolo Cho and Jacobus Li

See also

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |