Company rule in India facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Company rule in India

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1757–1858 | |||||||||||||||||||

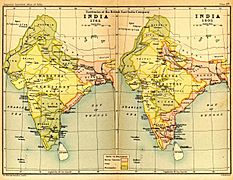

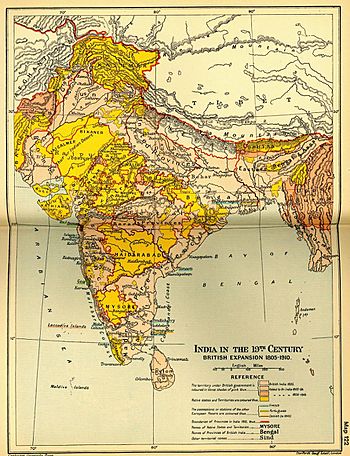

Areas of South Asia under Company rule (a) 1774–1804 and (b) 1805–1858 shown in two shades of pink

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Status | British colony | ||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Calcutta (1757–1858) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Official: 1773–1858: English; 1773–1836: Persian 1837–1858: primarily Urdu but also: Languages of South Asia. |

||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Administered by the East India Company functioning as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown and regulated by the British Parliament. | ||||||||||||||||||

| Governor-General | |||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1774–1785 (first)

|

Warren Hastings | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1857–1858 (last)

|

Charles Canning | ||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern | ||||||||||||||||||

| 23 June 1757 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 16 August 1765 | |||||||||||||||||||

|

• Anglo-Sikh Wars

|

1845–1846, 1848–1849 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2 August 1858 | |||||||||||||||||||

|

• Dissolution of the Company and assumption of direct administration by the British crown

|

2 August 1858 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1858 | 1,940,000 km2 (750,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Rupee | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Company rule in India was a time when the British East India Company controlled a large part of the Indian subcontinent. This period usually started in 1757, after the Battle of Plassey. In this battle, the local ruler of Bengal gave up his lands to the Company. Another important date is 1765, when the Company gained the right to collect taxes in Bengal and Bihar. By 1773, the Company had set up its main city in Calcutta and appointed its first Governor-General, Warren Hastings. This meant the Company was directly involved in ruling India.

Company rule ended in 1858. This happened after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, a big uprising against the Company. After the rebellion, the British government took over direct control of India. This new period was called the British Raj.

Contents

- How the Company Grew in India

- Important Governors-General

- How Company Rule Was Controlled

- Collecting Taxes (Revenue)

- Company Army and Civil Service

- Trade and Economy

- Justice System Changes

- Education in India

- Social Reforms by the British

- Post and Telegraph Services

- Railways in India

- Canals and Irrigation

How the Company Grew in India

The English East India Company started in 1600. It was a group of merchants who wanted to trade with countries in the East. They first set up a trading post in Masulipatnam on India's eastern coast in 1611. Then, in 1612, the Mughal Emperor Jahangir allowed them to build a factory (a trading post) in Surat.

Later, in 1640, they got permission to build another factory in Madras. In 1668, the island of Bombay was leased to the Company. This island had been given to England by Portugal as a wedding gift. A few decades later, the Company also set up a trading post in Calcutta, in the Ganges Delta. Many other European countries, like the Portuguese, Dutch, French, and Danish, also had companies trading in India. At first, no one knew the English Company would become so powerful.

Company's Power Grows Through Battles

The Company's power grew a lot after two important battles. In 1757, the Company, led by Robert Clive, won the Battle of Plassey. Then, in 1764, they won the Battle of Buxar. These victories made the Company very strong. They forced Emperor Shah Alam II to make them the diwan, which meant they could collect taxes in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. By 1773, the Company was the real ruler of large areas in the lower Ganges plains. They also expanded their control around Bombay and Madras.

After the Anglo-Mysore Wars (1766–1799) and the Anglo-Maratha Wars (1772–1818), the Company controlled large parts of India south of the Sutlej River. Once the Maratha Empire was defeated, no other local power could threaten the Company.

How the Company Took Control

The Company took control in two main ways:

- Direct Takeover: They directly took over Indian states and ruled them. These areas became known as British India. Examples include Rohilkhand (1801), Delhi (1803), Assam (1828), and Sindh (1843). Punjab and the North-West Frontier Province were taken over after the Second Anglo-Sikh War in 1849. However, Kashmir was sold to the Dogra dynasty and became a princely state.

- Treaties and Alliances: The Company also made treaties with Indian rulers. These rulers agreed to accept the Company's power but kept some control over their own lands. This was cheaper for the Company than direct rule. These agreements were called subsidiary alliances.

These alliances created many princely states, ruled by Hindu maharajas and Muslim nawabs. Some famous ones were Hyderabad (1798), Mysore (1799), and Rajputana (1818).

Important Governors-General

The Governors-General were the main leaders of the East India Company in India. Here are some of the most important ones and what happened during their time:

- Coins issued by the East India Company 1787 to 1840 CE

| Governor-General | Time in Office | Key Events |

|---|---|---|

| Warren Hastings | 1773 – 1785 | * Great Bengal famine of 1770 (1769–73)

|

| Charles Cornwallis | 1786 – 1793 | * Cornwallis Code (1793)

|

| Richard Wellesley | 1798 – 1805 | * Introduced Subsidiary alliance system

|

| Marquess of Hastings | 1813 – 1823 | * Anglo-Nepal War of 1814

|

| William Bentinck | 1828 – 1835 | * Banned Sati (widow burning) in 1829

|

| Marquess of Dalhousie | 1848 – 1856 | * Second Anglo-Sikh War (1848–1849)

|

| Charles Canning | 1856 – 1858 | * Hindu Widows' Remarriage Act, 1856

|

How Company Rule Was Controlled

At first, the East India Company's trading posts in India were run by local councils of merchants. These councils didn't have much power, and there wasn't enough control over the Company's actions. This led to some Company officers becoming very rich in unfair ways.

After the Battle of Plassey, Britain started paying more attention to India. By 1772, the Company needed loans from the British government. People in London worried that the Company's bad practices could spread to Britain. So, in 1773, the British Parliament passed the Regulating Act.

New Rules for the Company

The Regulating Act said that the Company could rule India on behalf of the British Crown. But it also meant the British government and Parliament would watch over the Company. The Company had to report everything about its civil, military, and tax matters in India to the British government.

The Act also made the Bengal Presidency more powerful than the other presidencies (Madras and Bombay). It appointed a Governor-General (Warren Hastings) and four councillors to manage Bengal and oversee all Company operations in India. The Act also tried to stop corruption by banning Company servants from private trading or taking gifts from Indians.

Later, in 1784, Pitt's India Act was passed. This Act kept the East India Company in charge of India's politics but created a Board of Control in England. This Board was there to supervise the Company and stop its shareholders from interfering in India's government. From 1784 onwards, the British government had the final say on all major appointments in India.

In 1813, the British Parliament ended the Company's trade monopoly in India, except for tea and trade with China. This opened India to private businesses and missionaries. By 1833, the British Parliament made the Company an agent for running British India. The Governor-General of Bengal became the Governor-General of India, with power over all of British India.

-

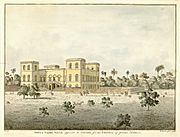

Government House, Fort St. George, Madras, the headquarters of the Madras Presidency.

-

Warren Hastings, the first Governor-General of Fort William (Bengal).

Collecting Taxes (Revenue)

Before 1765, in Bengal, local landlords called zamindars collected taxes for the Mughal emperor. The land itself belonged to the state, not the zamindars. The zamindars kept a part of the taxes for themselves and gave the rest to the state.

When the East India Company got the right to collect taxes in Bengal in 1765, they didn't have enough trained people. So, they often hired others to collect taxes. This new way of collecting taxes might have made the terrible Bengal famine of 1770 even worse. Millions of people died, and the Company did little to help.

New Tax Systems

In 1772, under Warren Hastings, the Company started collecting taxes directly in the Bengal Presidency. They set up tax offices in Calcutta and Patna.

In 1793, Governor-General Lord Cornwallis introduced the Permanent Settlement in Bengal. This system made the land tax fixed forever. It also gave zamindars full ownership rights to the land. The idea was that if zamindars knew the tax was fixed, they would improve their land and grow more crops, keeping the extra profit. However, this often meant that peasants had to pay more, and their traditional rights were not protected. Many zamindars couldn't pay the high fixed tax and lost their lands.

In South India, a different system called ryotwari was used. This system, promoted by Thomas Munro, allowed the government to collect taxes directly from the peasant farmers, or ryots. The idea was to avoid having a "landlord class" and to make sure the benefits of Company rule reached everyone. However, even with this system, peasants sometimes struggled to pay the taxes. In the 1850s, it was found that some Company tax agents were using harsh methods to collect money.

Collecting land revenue was a huge job for the Company. It was their main source of income, making up about half of all government money in the mid-1800s.

-

A riverside scene in rural east Bengal (present-day Bangladesh), 1860.

-

A Kochh Mandai woman of east Bengal (now Bangladesh) with an agricultural knife and a freshly harvested jackfruit. (1860)

-

Paddy fields in the Madras Presidency, c. 1880. Two-thirds of the presidency fell under the Ryotwari system.

Company Army and Civil Service

When Warren Hastings became Governor-General in 1772, he quickly expanded the Company's army. They recruited soldiers, called Sepoys, from areas like eastern Awadh and Bihar. Many of these soldiers were high-caste Hindu Rajputs and Brahmins. The Company tried to respect their religious customs, for example, by providing separate dining areas and not requiring overseas service, which was seen as polluting to their caste.

| East India Company armies after the Re-organisation of 1796 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| British troops | Indian troops | ||

| Bengal Presidency | Madras Presidency | Bombay Presidency | |

| 24,000 | 24,000 | 9,000 | |

| 13,000 | Total Indian troops: 57,000 | ||

| Grand total, British and Indian troops: 70,000 | |||

The Bengal Army was used in many battles across India and even in places like Java and Ceylon. Unlike soldiers of Indian rulers, the Company's sepoys were paid well and on time. This, along with new weapons, made the Bengal army very strong and respected.

By 1806, the Company's armies had grown to 154,500 soldiers, making them one of the largest armies in the world.

| East India Company armies before the Vellore Mutiny of 1806 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Presidencies | British troops | Indian troops | Total |

| Bengal | 7,000 | 57,000 | 64,000 |

| Madras | 11,000 | 53,000 | 64,000 |

| Bombay | 6,500 | 20,000 | 26,500 |

| Total | 24,500 | 130,000 | 154,500 |

The 1857 Rebellion

In the Indian Rebellion of 1857, almost the entire Bengal army revolted. Many sepoys were unhappy because they felt they were losing their benefits after the Company took over Awadh in 1856. Also, soldiers were expected to serve in new, unfamiliar places without extra pay, which caused anger. However, the Bombay and Madras armies remained loyal. The rebellion led to a complete change in how the Indian army was organized in 1858.

Civil Service and Reforms

After 1784, the Company created an elite civil service. Talented young Britons would spend their careers managing customs, taxes, justice, and general administration in India. There were about 600 such men.

At first, the Company tried to adapt to Indian customs. But after 1813, this changed. Influenced by reformers and religious groups in Britain, the Company started to promote English culture and modern ideas in India. Christian missionaries became active, though they didn't convert many people. The British also tried to outlaw practices like sati (widow burning) and thuggee (ritual banditry). They also set up schools to teach the English language.

-

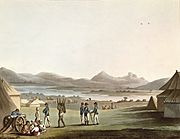

A Royal Artillery encampment at Arcot, Madras Presidency, 1804.

-

East India Company Sepoys (Indian infantrymen) in red coats outside Tipu Sultan's former summer palace in Bangalore, 1804.

-

Military Orphan School for private soldiers of the East India Company, Howrah, Bengal Presidency, 1794.

Trade and Economy

After gaining the right to collect taxes in Bengal in 1765, the Company stopped bringing in large amounts of gold and silver to pay for goods from India. Instead, they used the taxes collected in Bengal to buy goods to send back to Britain. This reduced the amount of money in Bengal.

| Years | Bullion (£) | Average per annum |

|---|---|---|

| 1708/9-1733/4 | 12,189,147 | 420,315 |

| 1734/5-1759/60 | 15,239,115 | 586,119 |

| 1760/1-1765/6 | 842,381 | 140,396 |

| 1766/7-1771/2 | 968,289 | 161,381 |

| 1772/3-1775/6 | 72,911 | 18,227 |

| 1776/7-1784/5 | 156,106 | 17,345 |

| 1785/6-1792/3 | 4,476,207 | 559,525 |

| 1793/4-1809/10 | 8,988,165 | 528,715 |

From 1780 to 1860, India's trade changed a lot. Before, India exported finished goods like fine cotton and silk. But during Company rule, India became an exporter of raw materials (like raw cotton, opium, and indigo) and a buyer of manufactured goods from Britain.

British cotton factories pushed their government to tax Indian imports and open Indian markets to British goods. By the 1830s, British textiles flooded Indian markets. The American Civil War also affected India's cotton economy. When American cotton was unavailable, demand for Indian cotton shot up, and prices quadrupled. But when the war ended in 1865, demand dropped, causing problems for Indian farmers.

Opium and Indigo Trade

The East India Company's trade with China also grew. Britain wanted a lot of Chinese tea. Since the Company didn't want to send gold from Britain, they decided to pay with opium, which was grown in India. Opium was banned in China, but there was a big illegal market for it. This led to the First Opium War, after which Britain gained access to five Chinese ports. By the mid-1800s, opium made up 40% of India's exports.

Another important export was indigo dye, used to make blue clothing. The Company encouraged British planters to grow indigo in Bengal and Bihar. However, the demand for indigo was unstable, leading to market crashes. This caused unhappiness among peasants, leading to the Indigo rebellion in Bengal in 1859–60.

-

Photograph of East India Company factory in Painam, Sonargaon, Bangladesh, a major producer of the celebrated Dhaka muslins.

-

"Mellor Mill" in Marple, England, built in 1790–1793 for manufacturing muslin cloth.

-

Opium Godown (Storehouse) in Patna, Bihar (c. 1814). Patna was the centre of the Company opium industry.

-

Indigo dye factory in Bengal. Bengal was the world's largest producer of natural indigo in the 19th century.

Justice System Changes

Before British control, the Nawab of Bengal oversaw justice. Local officials and landlords also handled cases.

Over time, the East India Company gained more power to manage justice in its main towns: Madras, Bombay, and Calcutta. In 1726, Mayor's Courts were set up for Europeans. These courts handled disputes between Europeans.

New Courts and Laws

After gaining control of Bengal in 1765, the Company got the right to handle civil justice. Criminal justice remained with the Nawab, following Islamic law.

Warren Hastings, the first Governor-General, reformed the justice system.

- Civil Courts: In each district, diwāni adālats (civil courts) were set up. European judges from the Company led these courts, helped by Hindu pandits and Muslim qazis who explained Indian law. There were also higher appeal courts.

- Criminal Courts: Similarly, nizāmat adālats (criminal courts) were created. These also had Indian officers supervised by Company officials.

In 1773, the British Parliament passed the Regulating Act, which created a Supreme Court in Calcutta. This court had a Chief Justice and three other judges, all chosen from British lawyers. The Supreme Court used English law. However, there was confusion about how the Supreme Court and the Company's own courts (the Adālats) would work together. This was clarified in 1781, making sure the Company's courts could operate independently.

Similar changes happened in Madras and Bombay, with Supreme Courts being set up in 1801 and 1823. This new justice system continued even after Company rule ended.

Education in India

From the start of Company rule in Bengal, officials were interested in educating Indians. At first, in the late 1700s and early 1800s, the Company supported Indian culture and learning. They wanted to understand India better and use that knowledge in government.

Early Education Goals

- Support Indian Culture: Some leaders, like Warren Hastings, believed the Company should support local learning. In 1781, Hastings founded the Madrasa 'Aliya in Calcutta for studying Arabic, Persian, and Islamic law.

- Gain Local Support: Other officials thought the Company should support Indian learning to gain the trust of its subjects. This led to the founding of the Benares Sanskrit College in Varanasi in 1791.

- Improve Administration: Some believed that Company officials would be better rulers if they understood Indian languages and cultures. This led to the founding of the College of Fort William in Calcutta in 1800.

These officials were called "Orientalists." They believed the Company's government should respect Indian traditions.

Shift to English Education

However, the Orientalists soon faced opposition from "Anglicists." Anglicists wanted to teach Indians in English to share Western knowledge. Many of them were missionaries who wanted to spread Christianity and promote social reforms.

By the 1830s, the Anglicists largely shaped education policy. Thomas Babington Macaulay's Minute on Indian Education in 1835 greatly influenced this. English became the main language of instruction, and Persian was removed as the official language of administration by 1837.

In 1854, Sir Charles Wood, a key British official, sent an Education Dispatch to the Governor-General. This plan outlined state-sponsored education for India, including:

- Setting up Departments of Public Instruction.

- Establishing universities in Madras, Bombay, and Calcutta, like the University of London.

- Creating teacher-training schools.

- Expanding government colleges and high schools.

- Greatly increasing local schools for elementary education.

- Providing grants to private schools.

The first universities were established in 1857 in Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras. By 1861, over 230,000 students were in public schools in India.

Social Reforms by the British

In the first half of the 19th century, the British passed laws to reform what they saw as unfair Indian practices. One example was the Hindu Widows' Remarriage Act, 1856. This law made it legal for Hindu widows to remarry, protecting some of their inheritance rights. Before this, many Hindu widows, even young ones, were expected to live a very strict life after their husband's death. However, despite the law, very few widows actually remarried.

Post and Telegraph Services

Postal Services

Before 1837, there was no single public postal service across all East India Company territories. Only important towns had courier services, and private individuals could use them only sometimes.

This changed in 1837 with the Indian Postal Act. A public postal service was set up across Company territory. Post offices opened in major towns, and postmasters were appointed. Sending a letter cost money, based on weight and distance. For example, sending a letter from Calcutta to Bombay cost one rupee.

In 1854, a new Indian Postal Act was passed. A Director-General now headed the entire postal department. Postage stamps were introduced, and rates were fixed only by weight, not distance. The cheapest letter rate was half an anna. By 1861, there were 889 post offices, delivering millions of letters and newspapers each year.

-

A semaphore "telegraph" signalling tower in Silwar (Bihar), 1823, before electric telegraphy.

Telegraphy

Before electric telegraphs, "telegraph" meant using semaphore signals (like flags). The Company thought about building tall signalling towers across India, but this network never fully happened.

By the mid-1800s, electric telegraphy became possible. In 1851, William Brooke O'Shaughnessy tested a telegraph service from Calcutta to Diamond Harbour. The experiment was a success. In 1852, Governor-General Lord Dalhousie got permission to build telegraph lines across India, connecting major cities like Calcutta, Agra, Bombay, and Madras.

By February 1855, these lines were built and used for sending paid messages. By 1857, the network had grown to 4,555 miles of lines. During the Indian Rebellion of 1857, rebels destroyed many lines. However, the Company used the remaining lines to warn its outposts. This showed how valuable the new technology was. The network was rebuilt and expanded after the rebellion.

Railways in India

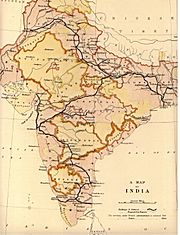

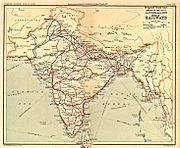

The first inter-city railway in England started in 1825. In 1845, the East India Company received requests from British companies to build a railway network in India. They asked Governor-General Lord Dalhousie to study if it was possible. The Company worried about floods, storms, insects, and finding skilled workers in India. They decided to build three test lines first.

Contracts were given in 1849 to:

- The East Indian Railway Company for a line from Howrah-Calcutta to Raniganj.

- The Great Indian Peninsular Railway Company for a line from Bombay to Kalyan.

- The Madras Railway Company for a line from Madras city to Arkonam.

Construction began on the East Indian Railways line in 1849. However, the first part of the Bombay-Kalyan line, a 21-mile stretch from Bombay to Thane, was completed first in 1853.

Lord Dalhousie strongly supported building railways in India in his Railway minute of 1853. He believed railways would bring political, social, and economic benefits. He suggested building main lines connecting major ports and cities. For example, a line from Calcutta to Lahore, and from Agra to Bombay. The Company's directors approved this plan.

The first part of the East Indian Railway line, from Howrah to Pandua, opened in 1854. The entire line to Raniganj was working by the time of the 1857 rebellion. The Great Indian Peninsular Railway extended its line to Poona, which involved building through steep hills and many tunnels.

British companies built these railways, and the Government of India guaranteed them a 5% return on their investment. All engineers had to come from England because there was no railway engineering knowledge in India. Building railways in India was a huge and complex project.

Even though railway construction had just begun when Company rule ended, the groundwork was laid. By the early 1900s, India had over 28,000 miles of railways, connecting most regions to ports. This became the fourth-largest railway network in the world.

-

The main railway lines proposed by Lord Dalhousie in 1853 (shown in red).

Canals and Irrigation

The East India Company started its first irrigation projects in 1817. These mostly involved improving or extending existing Indian irrigation systems. For example, they reinforced the Grand Anicut, a dam in the Kaveri river delta built 1,500 years earlier. They also extended ancient weirs on the Tungabhadra river.

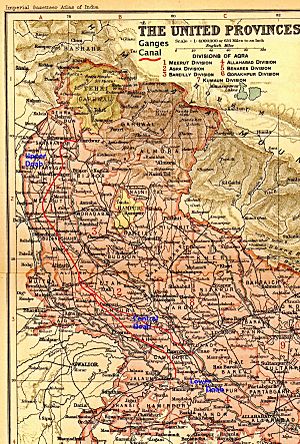

In northern India, the 150-mile long Western Jamna Canal was built by Firuz Shah Tughlaq in the 14th century. It irrigated lands in Hissar. This canal had become blocked over time but was repaired by British Army engineers and reopened in 1820. The Eastern Jamna Canal, built in the 18th century, was also reopened in 1830 after major repairs.

In the Punjab region, the Hasli Canal was extended by the British in the Bari Doab Canal works from 1850–1857. This canal supplied water to Lahore and Amritsar.

The Ganges Canal

The first completely new British irrigation project was the Ganges Canal, built between 1842 and 1854. The idea for this canal came after the terrible Agra famine of 1837–38, which made the Company realize the need for better irrigation.

The canal was designed by Sir Proby Thomas Cautley. Construction began in full swing in 1844. The Ganges Canal was 350 miles long, with another 300 miles of branch lines. It stretched from Haridwar to Kanpur and Etawah. The canal cost £2.15 million and was officially opened in 1854 by Lord Dalhousie.

The Ganges Canal was the largest canal ever attempted in the world at that time. It was five times longer than all the main irrigation lines of Lombardy and Egypt combined.

-

Watercolor (1863) titled "The Ganges Canal, Roorkee, Saharanpur District (U.P.)".

-

Photograph (1860) of the head works of the Ganges Canal in Haridwar taken by Samuel Bourne.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |