Ukiyo-e facts for kids

- Beauty Looking Back, Moronobu, late 17th century

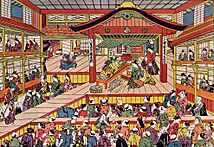

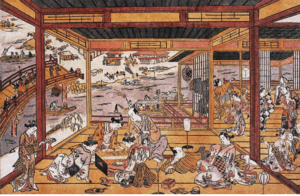

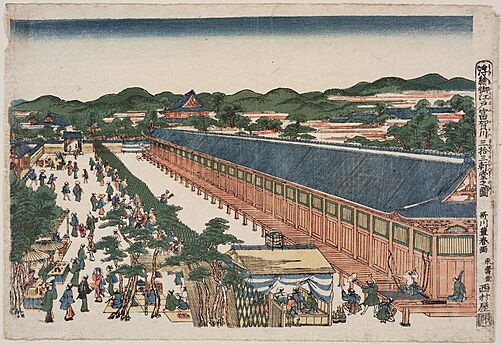

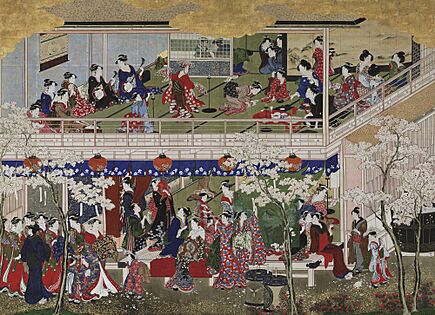

- Shibai Uki-e, Masanobu, c. 1741–1744

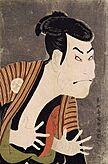

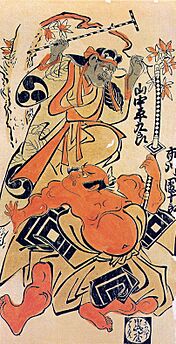

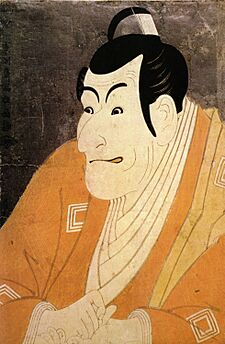

- Otani Oniji III, Sharaku, 1794

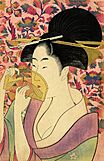

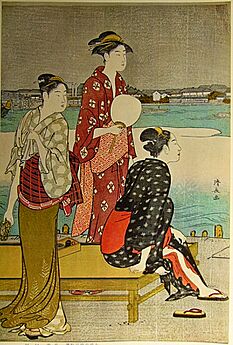

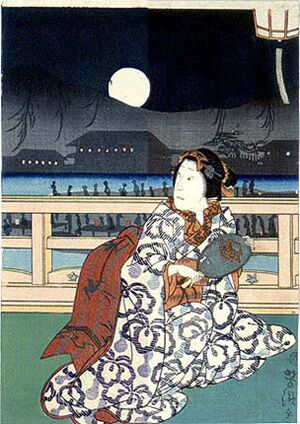

- Comb, Utamaro, 1798

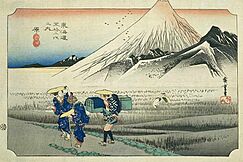

- Hara, 13th station of The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō, Hiroshige, 1833–34

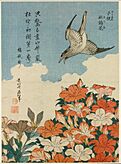

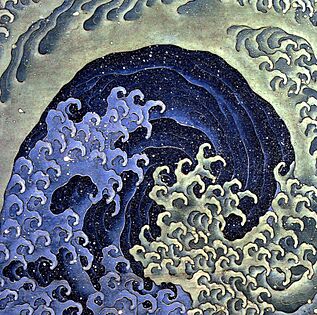

- Cuckoo and Azaleas, Hokusai, 1828

- Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre, Kuniyoshi, c. 1844

Ukiyo-e is a type of Japanese art that was very popular from the 1600s to the 1800s. Artists made these artworks as woodblock prints and paintings. They showed many different things, like beautiful women, kabuki actors, and sumo wrestlers. They also pictured scenes from history, folk tales, travel, and nature (plants and animals). The word ukiyo-e (浮世絵) means 'pictures of the floating world'.

In 1603, the city of Edo (now Tokyo) became the capital of Japan. The merchant class, called chōnin, became very wealthy. They enjoyed new forms of entertainment, like kabuki theater. The term ukiyo ('floating world') described this fun, lively way of life. Ukiyo-e art was popular with these wealthy merchants. They bought prints and paintings to decorate their homes.

The first ukiyo-e artworks appeared in the 1670s. Hishikawa Moronobu made paintings and simple black-and-white prints of beautiful women. Over time, artists started adding color. By the 1740s, artists like Okumura Masanobu used several woodblocks to print different colors. In the 1760s, Suzuki Harunobu's "brocade prints" (nishiki-e) became popular. These were full-color prints made with ten or more blocks for each design.

Most ukiyo-e works were prints, not paintings. Artists usually did not carve their own woodblocks. Instead, a team worked together:

- The artist designed the picture.

- The carver cut the design into woodblocks.

- The printer put ink on the blocks and pressed them onto special handmade paper.

- The publisher paid for everything and sold the artworks.

Because printing was done by hand, printers could create special effects. For example, they could blend colors on the block, called bokashi.

Some of the most famous ukiyo-e artists created portraits of beauties and actors. These masters include Torii Kiyonaga, Utamaro, and Sharaku. This was in the late 1700s. In the 1800s, other masters continued the tradition. Hokusai created The Great Wave off Kanagawa, one of the most famous Japanese artworks. Hiroshige made The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō. After these artists passed away, ukiyo-e art became less popular. This was also due to new technologies and changes in Japan after the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

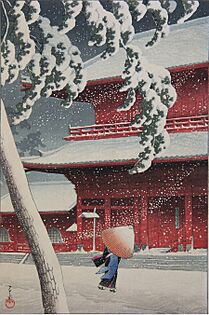

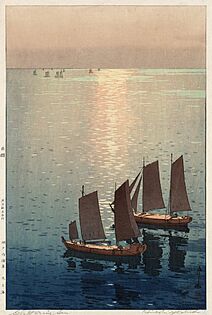

However, Japanese printmaking saw a comeback in the 1900s. The shin-hanga ('new prints') style focused on traditional Japanese scenes. It was popular with Westerners. The sōsaku-hanga ('creative prints') movement was different. Artists designed, carved, and printed their own works. Prints today still focus on individual expression. They often use techniques from Western art.

Ukiyo-e art helped shape how the Western world saw Japanese art in the late 1800s. Especially the landscapes by Hokusai and Hiroshige. From the 1870s, Japonism became a big trend. It strongly influenced French artists like Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, and Claude Monet. It also affected Vincent van Gogh and Art Nouveau artists like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

History of Ukiyo-e Art

Early Japanese Art Styles

Japanese art before ukiyo-e followed two main paths. One was the Yamato-e style, which focused on Japanese themes. The other was kara-e, inspired by Chinese art. This included ink wash paintings. The Kanō school of painting mixed both styles.

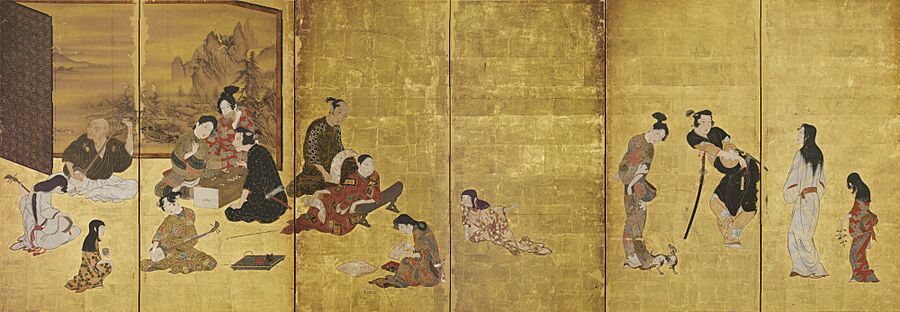

For a long time, rich families and religious groups supported Japanese art. Until the 1500s, paintings rarely showed the lives of everyday people. Even when they did, these artworks were expensive. Later, cheaper paintings appeared for townspeople. These showed beautiful women and scenes from theaters. These early artworks were made by hand, so not many could be produced. This changed with the rise of mass-produced woodblock printing.

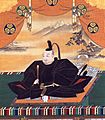

During a long period of civil war in the 1500s, powerful merchants grew wealthy. These merchants, called machishū, supported the arts. This led to a rebirth of classical art in the late 1500s and early 1600s. In the early 1600s, Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616) united Japan. He became the shōgun (military ruler) and set up his government in Edo (modern Tokyo). He made powerful lords (Daimyō) visit Edo every other year. This caused many men to move to the city for work. Edo grew from 1,800 people to over a million by the 1800s.

The new government ended the merchants' political power. It divided people into four social classes, with samurai at the top and merchants at the bottom. Even so, merchants benefited most from Edo's growing economy. Their wealth allowed them to enjoy entertainment and buy art for their homes. This was something they could not afford before.

Woodblock printing in Japan started around 770 CE. For a long time, it was only used for Buddhist images. Around 1600, movable type appeared. But carving text onto woodblocks was more efficient for Japanese writing. In Kyoto, Hon'ami Kōetsu and publisher Suminokura Soan combined printed text and images in books. Later, illustrated folk tales called tanrokubon were mass-produced. Illustrated books about city life also became popular. After the Great Fire of Meireki in 1657, Edo was rebuilt. Publishing illustrated books boomed in the growing city.

The word ukiyo (浮世) ('floating world') sounded like an older Buddhist term meaning 'world of sorrow'. But the new term described the fun, lively spirit of the time for common people.

Ukiyo-e Begins (Late 1600s – Early 1700s)

The first ukiyo-e artists came from painting backgrounds. They used a style of outlined shapes. This outlining became key to ukiyo-e.

Around 1661, paintings called Portraits of Kanbun Beauties became popular. These paintings from the Kanbun era (1661–1673) were the start of ukiyo-e as its own art style. Some scholars think Iwasa Matabei (1578–1650) was the founder of ukiyo-e. He might have painted the unsigned Hikone screen. This screen shows everyday life in a refined style.

To meet the growing demand for ukiyo-e, Hishikawa Moronobu (1618–1694) made the first ukiyo-e woodblock prints. By 1672, Moronobu was so successful he started signing his work. He was a very busy artist who worked in many styles. He created an important way of showing female beauties. Most importantly, he made single-sheet prints, not just book illustrations. These could be sold alone or as part of a series. Moronobu's style became very popular. Many artists copied him, like Sugimura Jihei. This marked the start of a new art form for everyone.

After Moronobu died, Torii Kiyonobu I and Kaigetsudō Ando copied his style. They focused on human figures, not backgrounds. Kiyonobu and his Torii school made prints of kabuki actors (yakusha-e). Ando and his Kaigetsudō school made prints of beautiful women (bijin-ga). Ando's school created a standard image of women that was easy to mass-produce. This made their art very popular. The Kaigetsudō school ended after Ando was exiled in 1714.

The paintings of Miyagawa Chōshun (1683–1752) showed early 1700s life with soft colors. Chōshun did not make prints. The Miyagawa school he started specialized in romantic paintings. Their style was more refined than the Kaigetsudō school. Chōshun allowed his students more artistic freedom. Hokusai was later part of this group.

- Early ukiyo-e masters

Color Prints Emerge (Mid-1700s)

Even the first black-and-white prints sometimes had color added by hand. This was for special orders. In the early 1700s, people wanted more color. Artists used red lead ink for tan-e prints. Later, they used pink safflower ink for beni-e prints. Then came lacquer-like ink for urushi-e. In 1744, benizuri-e prints were the first successful color prints. They used multiple woodblocks, one for each color, usually pink and green.

Okumura Masanobu (1686–1764) was a great artist who promoted his own work. He was important during the time when printing techniques quickly improved. He opened a shop in 1707 and mixed styles from different art schools. His romantic images included new ideas. He used geometrical perspective in the uki-e genre in the 1740s. He also made long, narrow hashira-e prints. He combined pictures and poetry in prints that included his own haiku poems.

Ukiyo-e reached its peak in the late 1700s with full-color prints. These were developed after Edo became rich again. These popular color prints were called nishiki-e, or 'brocade pictures'. Their bright colors looked like fancy Chinese fabrics. The first ones were expensive calendar prints. They were printed with many blocks on very fine paper using thick, bright inks. These prints had the number of days for each month hidden in the design. They were sent as New Year's greetings. Later, the blocks were reused for regular sales.

The delicate prints of Suzuki Harunobu (1725–1770) were among the first to use complex color designs. They were printed with up to a dozen separate blocks for different colors. His graceful prints reminded people of classic Japanese poetry and painting. Harunobu was the most important ukiyo-e artist of his time. His colorful nishiki-e prints became popular from 1765. This led to less demand for prints with limited colors.

After Harunobu died in 1770, artists moved away from his ideal style. Katsukawa Shunshō (1726–1793) and his school made portraits of kabuki actors. These showed the actors' real features more accurately. Koryūsai (1735 – c. 1790) and Kitao Shigemasa (1739–1820) were also important. They focused on modern city fashions and famous real-life entertainers. Koryūsai was perhaps the most productive ukiyo-e artist of the 1700s. The Kitao school that Shigemasa started was one of the main schools in the late 1700s.

In the 1770s, Utagawa Toyoharu made many perspective prints (uki-e). He showed a great skill in Western perspective techniques. Toyoharu's works helped make landscapes a main subject in ukiyo-e. Before, landscapes were just backgrounds. In the 1800s, Western perspective was used in the detailed landscapes of artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige. Hiroshige was part of the Utagawa school that Toyoharu founded. This school became very influential. It produced works in many more styles than any other school.

- Early color ukiyo-e

-

Two Lovers Beneath an Umbrella in the Snow Harunobu, c. 1767

Peak Period (Late 1700s)

Even with tough economic times, ukiyo-e art reached its best in the late 1700s. Especially during the Kansei era (1789–1791). The art from this time focused on beauty and balance.

In the 1780s, Torii Kiyonaga (1752–1815) showed traditional ukiyo-e subjects. These included beauties and city scenes. He printed them on large sheets of paper, often in sets of two or three. His works were realistic pictures of ideal women in stylish clothes. They were shown in beautiful places. He also made realistic portraits of kabuki actors.

A law in 1790 required prints to have a censor's approval. This rule became stricter over the years. Artists could be punished harshly. By 1799, even early sketches needed approval. Some artists, like Toyokuni, had their works stopped in 1801. Utamaro was even jailed in 1804 for making prints of a 16th-century leader.

Utamaro (c. 1753–1806) became famous in the 1790s. He made "large-headed pictures of beautiful women" (bijin ōkubi-e). These focused on the head and upper body. Utamaro used different lines, colors, and printing methods. He showed small differences in the faces and expressions of women from all walks of life. His unique beauties were very different from the usual perfect, standard images. By the end of the 1790s, Utamaro's work became less good. He died in 1806.

The mysterious artist Sharaku appeared suddenly in 1794 and vanished ten months later. His prints are among the most famous ukiyo-e works. Sharaku made striking portraits of kabuki actors. He showed them with more realism, highlighting the differences between the actor and the character. His expressive, twisted faces were very different from the calm, mask-like faces of other artists. Sharaku's work was not always well-received. In 1795, his prints stopped appearing. His real identity is still unknown. Utagawa Toyokuni (1769–1825) made kabuki portraits that Edo people found easier to like. He focused on dramatic poses and avoided Sharaku's realism.

Ukiyo-e in the late 1700s was consistently high quality. But Utamaro and Sharaku's works often get the most attention. One of Kiyonaga's students, Eishi (1756–1829), left his job as a painter for the shōgun to design ukiyo-e. The Utagawa school became the most important ukiyo-e producer in the late Edo period.

Edo was the main center for ukiyo-e. Another important center was in the Kamigata region, around Kyoto and Osaka. Unlike Edo prints, Kamigata prints mostly showed kabuki actors. The style of Kamigata prints was similar to Edo prints until the late 1700s. This was partly because artists often moved between the two areas. Kamigata prints tend to have softer colors and thicker pigments. In the 1800s, many prints were designed by kabuki fans and other non-professional artists.

- Masters of the peak period

-

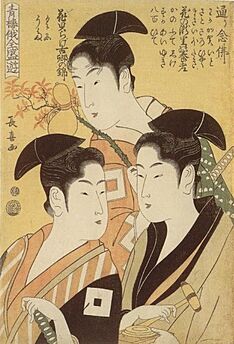

Three Beauties of the Present Day Utamaro, c. 1793

-

Ichikawa Ebizo as Takemura Sadanoshin Sharaku, 1794

-

Onoe Eisaburo I Toyokuni, c. 1800

Later Years: Nature and Landscapes (1800s)

The Tenpō Reforms of 1841–1843 tried to stop people from showing off luxury. Because of this, many ukiyo-e artists designed travel scenes and nature pictures. They especially focused on birds and flowers. Landscapes had not been a major focus since Moronobu. But in the late Edo period, landscapes became a main art style. This was especially true with the works of Hokusai and Hiroshige. Today, landscapes are what many Westerners think of when they hear "ukiyo-e". Japanese landscapes were different from Western ones. They focused more on imagination and atmosphere than on strict realism.

The artist Hokusai (1760–1849) had a long and varied career. His work is known for not being sentimental. He focused on shapes and forms, influenced by Western art. He illustrated novels and created the Hokusai Manga sketchbooks. He made landscapes popular with his Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji. This series includes his most famous print, The Great Wave off Kanagawa. Hokusai's colors were bold and flat. His subjects were not just entertainment areas. He showed the lives of everyday people at work. Other artists like Eisen, Kuniyoshi, and Kunisada also made landscape prints in the 1830s. Their prints had bold designs and striking effects.

The Utagawa school produced some masters during this later period. The very productive Kunisada (1786–1865) was one of the best at making portraits of women and actors. Eisen (1790–1848) was also good at landscapes. Perhaps the last important artist of this time was Kuniyoshi (1797–1861). He tried many different themes and styles, like Hokusai. His historical scenes of warriors in battle were popular. He also made landscapes and satirical scenes. It was rare to see satire during the strict Edo period. Kuniyoshi's ability to do this showed that the government was weakening.

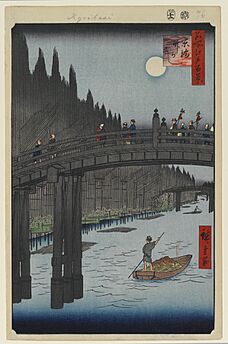

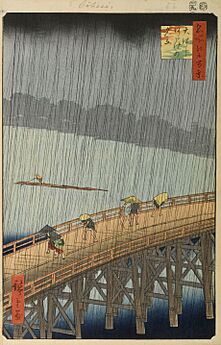

Hiroshige (1797–1858) is seen as Hokusai's biggest rival. He specialized in pictures of birds and flowers, and calm landscapes. He is best known for his travel series, like The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō. His work was more realistic and used softer colors than Hokusai's. Nature and the seasons were key parts of his art. Mist, rain, snow, and moonlight were often in his pictures. Hiroshige's students continued his landscape style into the Meiji era.

- Masters of the late period

-

Dawn at Futami-ga-ura Kunisada, c. 1832

-

Decline of Ukiyo-e (Late 1800s)

After Hokusai and Hiroshige died, and after the Meiji Restoration in 1868, ukiyo-e art declined. Japan quickly adopted Western ways. Woodblock printing was used for newspapers and faced competition from photography. Pure ukiyo-e artists became rare. People's tastes changed, and the art was seen as old-fashioned. Artists still made some good works, but by the 1890s, the tradition was almost gone.

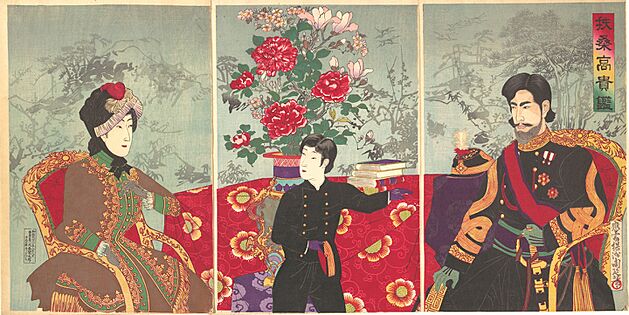

New synthetic colors from Germany started replacing traditional ones in the mid-1800s. Many prints from this time used a bright red. They were called aka-e ('red pictures'). Artists like Yoshitoshi (1839–1892) led a trend in the 1860s. They made gruesome scenes of murders, ghosts, and monsters. His One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (1885–1892) showed many different themes with a moon. Kiyochika (1847–1915) is known for prints showing Tokyo's modernization. He showed railways and Japan's wars with China and Russia. Chikanobu (1838–1912) turned to prints in the 1870s. He focused on the imperial family and Western influences on Japanese life.

- Meiji-era ukiyo-e

-

Mirror of the Japanese Nobility Chikanobu, 1887

-

From One Hundred Aspects of the Moon Yoshitoshi, 1891

Ukiyo-e Comes to the West

Before the mid-1800s, Westerners did not pay much attention to Japanese art. They often did not see it as different from other Asian art. Swedish naturalist Carl Peter Thunberg was one of the first Westerners to collect Japanese prints. He spent a year at a Dutch trading post in Japan. Ukiyo-e exports slowly grew. By the early 1800s, a Dutch merchant's collection caught the eye of art lovers in Paris.

In 1853, American Commodore Matthew Perry arrived in Edo. This led to the Convention of Kanagawa in 1854. It opened Japan to the outside world after over two centuries of isolation. Ukiyo-e prints were among the items Perry brought back to the United States. These prints had been in Paris since at least the 1830s. By the 1850s, there were many of them. People had mixed feelings about them. Even when praised, ukiyo-e was often thought to be less good than Western art. Western art focused on realistic perspective and anatomy. Japanese art gained attention at the International Exhibition of 1867 in Paris. It became popular in France and England in the 1870s and 1880s. Hokusai and Hiroshige's prints were very important in how the West saw Japanese art. At the time, woodblock printing was common in Japan. The Japanese did not think it had much lasting value.

Early European supporters of ukiyo-e included writer Edmond de Goncourt and art critic Philippe Burty. Burty created the term Japonism. Stores selling Japanese goods opened, like Siegfried Bing's in 1875. From 1888 to 1891, Bing published Artistic Japan magazine. He also organized an ukiyo-e exhibition in Paris in 1890. Artists like Mary Cassatt attended.

American Ernest Fenollosa was an early Western fan of Japanese culture. He did a lot to promote Japanese art. Hokusai's works were a big part of his first exhibition. This was when he became the first curator of Japanese art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. By the late 1800s, ukiyo-e became so popular in the West that prices went very high. Some artists, like Degas, traded their own paintings for these prints. Tadamasa Hayashi was a famous dealer in Paris. His Tokyo office sent many ukiyo-e prints to the West. Japanese critics later said he was taking Japan's national treasures. Japan did not notice this at first. Japanese artists were busy learning Western painting styles.

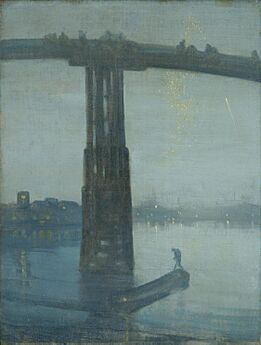

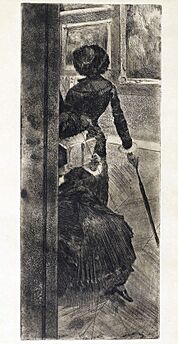

Japanese art, especially ukiyo-e prints, influenced Western art. This started with the early Impressionist artists. Painters began using Japanese themes and designs in the 1860s. The patterns in Manet's paintings were inspired by kimono patterns in ukiyo-e. Whistler focused on changing elements of nature, like in ukiyo-e landscapes. Van Gogh collected ukiyo-e prints. He even painted copies of prints by Hiroshige and Eisen. Degas and Cassatt showed everyday moments in their art. Their compositions and perspectives were influenced by Japan.

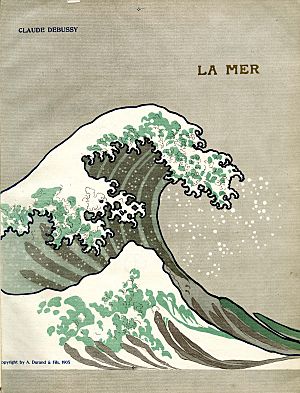

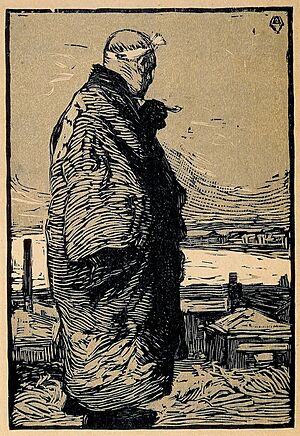

Ukiyo-e's flat perspective and solid colors especially influenced graphic designers. Toulouse-Lautrec's lithographs showed his interest in ukiyo-e's flat colors and outlined shapes. He also liked their subjects. He signed much of his work with his initials in a circle, like Japanese seals. Other artists influenced by ukiyo-e included Monet and Gauguin. French composer Claude Debussy was inspired by Hokusai and Hiroshige's prints for his music. This is clear in La mer (1905). Poets like Amy Lowell and Ezra Pound also found inspiration in ukiyo-e. Lowell published a poetry book called Pictures of the Floating World (1919).

- Ukiyo-e influence on Western art

-

Bamboo Yards, Kyōbashi Bridge Hiroshige, c. 1857–58

-

Nocturne: Blue and Gold – Old Battersea Bridge Whistler, c. 1872–75

-

Bridge in the Rain (after Hiroshige) van Gogh, 1887

-

Mary Cassatt at the Louvre: The Paintings Gallery Degas, c. 1779–80

-

Woman Bathing Cassatt, c. 1890–91

New Print Traditions (1900s)

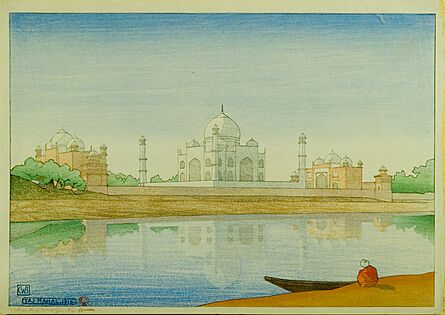

Travel sketchbooks became popular around 1905. The Japanese government encouraged travel to help citizens learn about their country. In 1915, publisher Shōzaburō Watanabe started using the term shin-hanga ("new prints"). These prints showed traditional Japanese subjects. They were made for foreign and wealthy Japanese buyers. Famous artists included Goyō Hashiguchi, known for his women portraits. Shinsui Itō brought modern ideas to images of women. Hasui Kawase made modern landscapes. Watanabe also published works by non-Japanese artists. Other publishers followed Watanabe's success. Some shin-hanga artists like Goyō and Hiroshi Yoshida even published their own work.

Artists of the sōsaku-hanga ('creative prints') movement controlled every step of printmaking. They designed, carved, and printed their own works. Kanae Yamamoto (1882–1946) is credited with starting this approach. In 1904, he made Fisherman using woodblock printing. This technique was not favored by the Japanese art world at the time. The Japanese Woodcut Artists' Association started in 1918. This marked the beginning of this movement. The movement valued artists' individual styles. So, there were no main themes or styles. Works ranged from abstract art by Kōshirō Onchi (1891–1955) to traditional scenes by Un'ichi Hiratsuka (1895–1997). These artists made prints for their own creative expression, not for a mass audience. They used more than just woodblocks.

Prints from the late 1900s and 2000s have continued this focus on individual expression. Artists use Screen printing, etching, mezzotint, and mixed media. These Western methods are now used alongside traditional woodcutting.

- Descendants of ukiyo-e

-

Glittering Sea, by Hiroshi Yoshida, 1926

Ukiyo-e Art Style

Early ukiyo-e artists knew a lot about classical Chinese painting. Over time, they developed a unique Japanese style. A key feature of most ukiyo-e prints is a clear, bold, flat line. The first prints were black and white, and these lines were the only printed part. Even with color, these lines remained important. In ukiyo-e, shapes are arranged in flat spaces. Figures are usually on a single depth level. Artists paid attention to vertical and horizontal lines, and details like patterns on clothes. Pictures were often not perfectly balanced. The view was often from unusual angles, like from above. Parts of images were often cut off, making them feel spontaneous. In color prints, the edges of most color areas are sharp, usually defined by lines. This style of flat colors is different from Western art. It is also different from other Japanese art styles for the rich, like subtle ink paintings.

Ukiyo-e's colorful, bold patterns and focus on changing fashions are different from traditional Japanese aesthetics. For example, wabi-sabi values simplicity and imperfection. shibui values subtlety and restraint. Ukiyo-e is more in line with the stylishness of iki.

Ukiyo-e uses a unique way of showing depth. It can look less developed than European paintings from the same time. Western-style perspective was known in Japan. Chinese methods also created depth using parallel lines. Sometimes, ukiyo-e works used both techniques. Western perspective gave an illusion of depth in the background. Chinese perspective was used more expressively in the foreground. Artists learned these techniques from Chinese Western-style paintings. Even after learning them, artists mixed them with traditional methods. They did this to fit their artistic needs. Other ways to show depth included a Chinese method. A large shape is in the foreground, a smaller one in the middle, and an even smaller one in the background. You can see this in Hokusai's Great Wave. There is a large boat in front, a smaller one behind it, and a small Mount Fuji behind them.

From early ukiyo-e, artists often posed women in a "serpentine posture." This means their bodies twisted unnaturally while facing backward. Some art historians think this came from traditional Japanese dance. Others say artists took artistic freedom. They made poses that looked relaxed but were physically impossible. This happened even when realistic perspective was used in other parts of the picture.

Themes and Types of Ukiyo-e

Common subjects were beautiful women ("bijin-ga"), kabuki actors ("yakusha-e"), and landscapes. The women shown were often entertainers at leisure. They promoted the fun found in entertainment areas. Artists paid less attention to how the women really looked. They followed the fashion of the time. Faces were standard, and bodies were tall and thin in one period, then small in another. Portraits of famous people were very popular. Especially those from kabuki and sumo, two of the most popular entertainments. While landscapes are now famous in ukiyo-e, they became popular later in its history.

Ukiyo-e prints started as book illustrations. Many of Moronobu's first single-page prints were originally from books he illustrated. Illustrated books (E-hon) were popular. They continued to be important for ukiyo-e artists. Later, Hokusai made the three-volume One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji. He also made the 15-volume Hokusai Manga. This was a collection of over 4,000 sketches of many real and imaginary subjects.

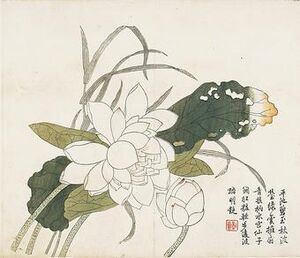

Nature scenes have always been important in Asian art. Artists carefully studied plants and animals. Ukiyo-e nature prints are called kachō-e, meaning "flower-and-bird pictures." But the style included more than just flowers or birds. Hokusai's detailed nature prints are known for making kachō-e a distinct art style.

The Tenpō Reforms of the 1840s stopped artists from showing actors and entertainers. So, artists turned to historical scenes. They showed ancient warriors or scenes from legends, literature, and religion. Famous warriors like Miyamoto Musashi (1584–1645) were often subjects. Artists also depicted monsters, supernatural beings, and heroes from Japanese and Chinese myths.

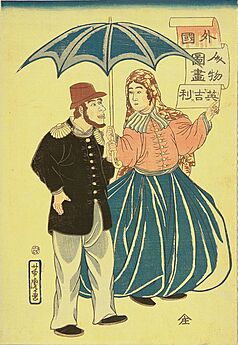

From the 1600s to the 1800s, Japan was isolated from most of the world. Trade was limited to a small island near Nagasaki. Strange pictures called Nagasaki-e were sold to tourists. These showed foreigners and their goods. In the mid-1800s, Yokohama became the main foreign settlement. Western knowledge spread from there. From 1858 to 1862, Yokohama-e prints showed the growing community of foreigners. They often showed Westerners and their technology.

Special prints included surimono. These were fancy, limited-edition prints for art lovers. They usually included a five-line poem. uchiwa-e were prints made for hand fans. These often show wear from being handled.

- Ukiyo-e genres

-

Yakusha-e print of two kabuki actors Sharaku, 1794

-

How Ukiyo-e Was Made

Paintings

Ukiyo-e artists often made both prints and paintings. Some focused on one or the other. Unlike older art styles, ukiyo-e painters used bright, sharp colors. They often outlined shapes with black ink, similar to print lines. Painters had more freedom than printmakers. They could use more techniques, colors, and surfaces. They painted with colors made from minerals or plants. Later, they used synthetic dyes from the West. Common surfaces were silk or paper hanging scrolls, handscrolls, or folding screens.

- Ukiyo-e paintings

Print Production

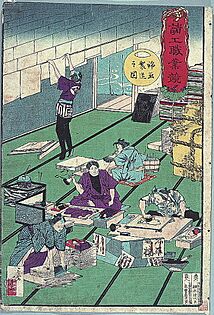

Ukiyo-e prints were made by teams of skilled workers. It was rare for artists to carve their own woodblocks. The work was divided into four parts:

- The publisher ordered, promoted, and sold the prints.

- The artists created the design.

- The woodcarvers prepared the woodblocks.

- The printers made the impressions on paper.

Usually, only the artist's and publisher's names were on the finished print.

Ukiyo-e prints were made by hand, not by machines. The artist drew the design on thin paper. This paper was glued to a cherry wood block. Oil was rubbed on it until the top layers of paper could be removed. This left a clear layer of paper for the carver to follow. The carver cut away the parts that were not black, leaving raised areas. These raised areas were inked to make the print. The original drawing was destroyed in this process.

Printers placed the blocks face up. This allowed them to change the pressure for different effects. They could also watch the paper soak up the water-based ink. Printers had many tricks. They could emboss the image by pressing an uninked woodblock onto the paper. This created textures, like patterns on clothing. Other effects included polishing the paper to make colors brighter. They also used varnish, overprinting, and dusting with metal or mica. Sprays could imitate falling snow.

Ukiyo-e prints were a commercial art form. The publisher was very important. Publishing was very competitive. Over a thousand publishers are known from this period. The number peaked around 250 in the 1840s and 1850s. Publishers owned the woodblocks and copyrights. From the late 1700s, they enforced copyrights through a guild. Prints that sold many copies were very profitable. Publishers could reuse the woodblocks without paying the artist again. Woodblocks were also traded or sold to other publishers. Publishers usually sold each other's goods in their shops. Besides the artist's seal, publishers put their own seals on the prints. Some were simple logos, others were detailed.

Print designers had to train before they could sign their own works. Young designers often had to pay for some or all of the woodblock carving costs. As artists became famous, publishers usually paid these costs. Artists could then ask for higher fees.

In old Japan, people could have many names. An artist's name included a family name and a personal art name. The family name often came from the art school they belonged to, like Utagawa or Torii. The personal art name often took a Chinese character from their master's name. For example, many students of Toyokuni (豊国) used the character "kuni" ((国)). This included Kunisada (国貞) and Kuniyoshi (国芳). Artists sometimes changed names during their careers. This can make it confusing. Hokusai used over a hundred names in his 70-year career.

Prints were sold widely. By the mid-1800s, thousands of copies of a print could be made. Shops and traveling sellers sold them at prices that wealthy townspeople could afford. Sometimes, the prints advertised kimono designs by the artist. From the late 1600s, prints were often sold as part of a series. Each print had the series name and its number. This was a good marketing idea. Collectors bought every new print to complete their sets. By the 1800s, series like Hiroshige's Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō had dozens of prints.

- Making ukiyo-e prints

-

The woodblock printing process, Kunisada, 1857. This is a fantasy version, showing only well-dressed "beauties" working. In reality, few women worked in printmaking.

Color Print Production

While colour printing in Japan started in the 1640s, early ukiyo-e prints only used black ink. Color was sometimes added by hand. Red lead ink was used in tan-e prints. Later, pink safflower ink was used in beni-e prints. Color printing came to books in the 1720s and to single prints in the 1740s. A different block was used for each color. Early colors were limited to pink and green. Over the next two decades, techniques allowed up to five colors. The mid-1760s brought full-color nishiki-e prints. These were made from ten or more woodblocks. To keep the blocks aligned, registration marks called kentō were used.

Printers first used natural dyes from minerals or plants. These dyes were clear. This allowed many colors to be mixed from red, blue, and yellow. In the 1700s, Prussian blue became popular. It was very noticeable in the landscapes of Hokusai and Hiroshige. Also popular was bokashi. This is where the printer created color gradients or blended colors. Cheaper, more consistent synthetic dyes arrived from the West in 1864. These colors were harsher and brighter than traditional ones. The Japanese government promoted their use as part of Westernization.

Collecting and Caring for Ukiyo-e

The government limited the size of homes for common people. Ukiyo-e works were small, perfect for these homes. We do not know much about who bought ukiyo-e paintings. They cost much more than prints, so wealthy merchants likely bought them. Most surviving prints are from later periods. This is because more were made in the 1800s. The older a print is, the less likely it is to have survived. Ukiyo-e was mostly linked to Edo. Visitors to Edo often bought them as souvenirs. Shops might specialize in items like fans or offer many different prints.

The ukiyo-e print market was very diverse. It sold to many different people, from day workers to rich merchants. We do not have much exact information about how many were made or sold. Experts have to guess about who bought ukiyo-e.

It is hard for experts to know the exact prices of prints. Records are scarce, and there was a lot of variety in quality, size, and demand. Prices also changed over time. In the 1800s, records show prints sold for as low as 16 mon to 100 mon for special editions. For comparison, a bowl of soba noodles in the early 1800s usually cost 16 mon.

The colors in ukiyo-e prints can fade easily in light. So, displaying them for a long time is not good. The paper also gets damaged by acidic materials. Storage boxes and folders must be acid-free. Prints should be checked regularly for problems. They should be stored in a humidity of 70% or less to prevent mold.

The paper and colors in ukiyo-e paintings are sensitive to light and humidity changes. Mounts must be flexible. In the Edo era, paintings were mounted on long-fibered paper. They were kept rolled up in wooden boxes. In museums, display times are very limited to protect them from light and pollution. Scrolls are unrolled and re-rolled carefully. Humidity levels for scrolls are usually between 50% and 60%. If it is too dry, scrolls become brittle.

Because ukiyo-e prints were mass-produced, collecting them is different from collecting paintings. There are big differences in condition, rarity, cost, and quality. Prints might have stains, wormholes, tears, or creases. Colors might have faded. Carvers might have changed colors or designs in later printings. If cut after printing, the paper might be trimmed. The value of prints depends on the artist's fame, the print's condition, how rare it is, and if it is an original printing. Even good later printings are worth less than originals.

Ukiyo-e prints often had many editions. Sometimes, changes were made to the blocks in later editions. Prints made from re-cut woodblocks also exist. These can be legitimate copies or fakes. Takamizawa Enji (1870–1927) made ukiyo-e copies. He developed a way to re-cut woodblocks to print fresh color on faded originals. He then used tobacco ash to make the new ink look old. He sold these refreshed prints as originals. American architect Frank Lloyd Wright was one of the collectors he tricked.

Ukiyo-e artists are referred to in the Japanese style, with the family name first. Famous artists like Utamaro and Hokusai are often called by their personal name alone. Dealers usually refer to ukiyo-e prints by their standard sizes. The most common are the 34.5-by-22.5-centimetre (13.6 in × 8.9 in) aiban, the 22.5-by-19-centimetre (8.9 in × 7.5 in) chūban, and the 38-by-23-centimetre (15.0 in × 9.1 in) ōban. Exact sizes vary, and paper was often trimmed after printing.

Many of the best ukiyo-e collections are outside Japan. The National Library of France started a collection in the early 1800s. The British Museum began a collection in 1860. By the late 1900s, it had 70,000 items. The largest collection, over 100,000 items, is at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Ernest Fenollosa donated his collection there in 1912. The first ukiyo-e exhibition in Japan was likely in 1925. Kōjirō Matsukata collected his prints in Paris during World War I. He later donated them to the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. The largest collection in Japan is at the Japan Ukiyo-e Museum in Matsumoto. It has 100,000 pieces.

Images for kids

-

Early woodblock print, Hishikawa Moronobu, late 1670s or early 1680s

See also

In Spanish: Ukiyo-e para niños

In Spanish: Ukiyo-e para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |