Toyohara Chikanobu facts for kids

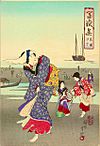

Toyohara Chikanobu (1838–1912), also known as Yōshū Chikanobu, was a famous Japanese artist. He was well-known for his many woodblock prints during the Meiji period in Japan. His art often showed the changes happening in Japan as it moved from the old samurai ways to a more modern time.

Artist's Names

Chikanobu used the art name "Yōshū Chikanobu" when he signed his artworks. An art name is like a stage name for an artist. His real name was Hashimoto Naoyoshi, which was shared after he passed away.

Some of his first artworks were signed "studio of Yōshū Chikanobu," and a few were just signed "Yōshū." One artwork from 1879 even has the signature "Yōshū Naoyoshi."

A portrait of Emperor Meiji in the British Museum says it was "drawn by Yōshū Chikanobu by special request." You won't find any works signed "Toyohara Chikanobu" or "Hashimoto Chikanobu."

Military Life

Before becoming a full-time artist, Chikanobu was a warrior. He was a loyal follower of the Sakakibara family in a place called Takada. When the Tokugawa Shogunate (Japan's old military government) ended, he joined a group called the Shōgitai. He even fought in a battle in Ueno.

Later, he joined other loyal warriors in Hakodate, Hokkaidō. He fought bravely in the Battle of Hakodate at a special star-shaped fort called Goryōkaku. He was known for his courage during these battles. After his group surrendered, he was sent back to his home area.

Artistic Journey

In 1875, Chikanobu decided to become a full-time artist and moved to Tokyo. He started working as an artist for a newspaper called Kaishin Shimbun. He also created many nishiki-e artworks, which are colorful woodblock prints.

When he was younger, he studied a painting style called Kanō. But he became very interested in ukiyo-e, which means "pictures of the floating world." This art style often showed everyday life, famous actors, and beautiful women. He learned from different teachers, including a student of Keisai Eisen and then joined the school of Ichiyūsai Kuniyoshi. After Kuniyoshi passed away, he continued his studies with Kunisada.

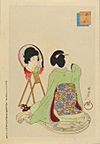

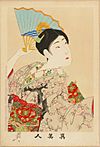

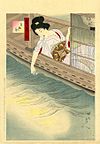

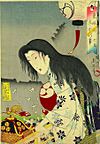

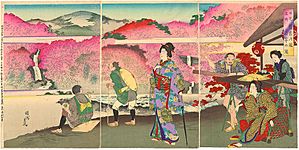

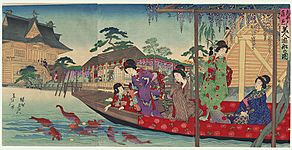

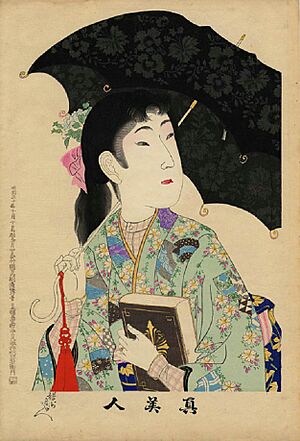

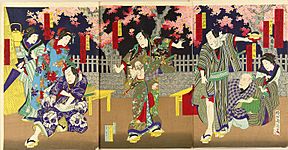

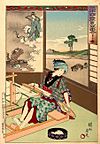

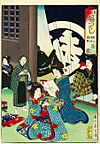

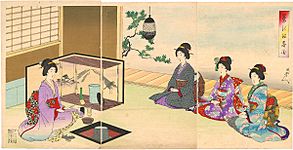

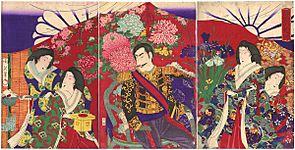

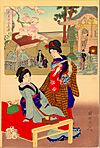

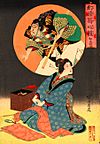

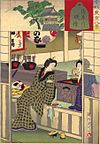

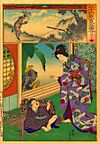

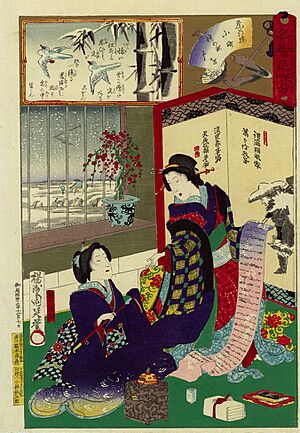

Like many ukiyo-e artists, Chikanobu drew many different things. His art showed everything from Japanese myths to battle scenes from his own time, and even women's fashion. He also drew famous kabuki actors in their roles, capturing their dramatic poses. Chikanobu was especially good at bijinga, which are pictures of beautiful women. He showed how women's clothes, hairstyles, and makeup changed over time, including both traditional Japanese and new Western styles. His art truly captured the shift from the samurai era to modern Meiji Japan.

Chikanobu is known as a Meiji period artist, but he also drew scenes from older Japanese history. For example, one print shows an event from the 1855 Ansei Edo earthquake. He also created many prints about the Satsuma Rebellion and Saigō Takamori, showing the unrest in Japan during that time. He even made prints about current events, like the 1882 Imo Incident in Korea.

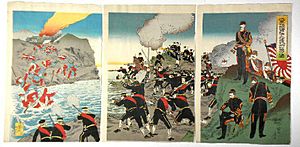

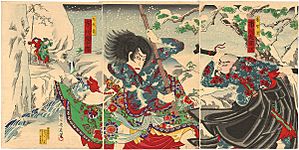

Many of Chikanobu's war prints, called sensō-e, were made as triptychs (three-panel prints). These prints documented events like the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895). For instance, his "Victory at Asan" print was released with a story about the battle that happened on July 29, 1894.

Other artists, like Yōsai Nobukazu and Yōdō Gyokuei, were influenced by Chikanobu's work.

Art Styles and Topics

Battle Scenes

Chikanobu created many exciting battle scenes, known as sensō-e. Here are some examples:

- The Boshin War (1868–1869)

- The Satsuma Rebellion (1877)

- The Jingo Incident in Korea (1882)

- The First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895)

- The Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905)

Warrior Prints

Chikanobu also made Musha-e, which are prints showing brave warriors.

Beauty Pictures

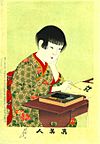

His "beauty pictures," called Bijin-ga, show beautiful women and their daily lives.

Historical Pictures

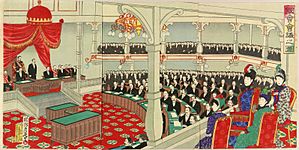

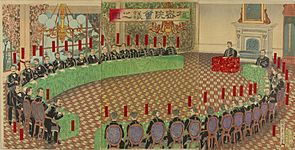

Chikanobu also drew Reshiki-ga, which are historical scenes. These include both recent events from the Meiji era and stories from ancient history.

Recent (Meiji era) history:

Ancient history:

Famous Places

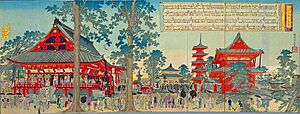

His Meisho-e prints show beautiful scenic spots in Japan.

Portraits

Chikanobu also created Shōzō-ga, which are portraits of important people.

Enlightenment Pictures

These "enlightenment pictures," or Bunmei kaika-e, show how Japan was adopting new Western ideas and styles during the Meiji era.

Theatre Scenes

Chikanobu made many Yakusha-e, which are scenes from kabuki plays or portraits of kabuki actors. Kabuki is a traditional Japanese theater known for its dramatic makeup and costumes.

Memorial Prints

Shini-e are "memorial prints" made to honor people who have passed away, often famous actors or artists.

Women's Pastimes

These prints, called joreishiki, show "Etiquette and Manners for Women" and depict women engaged in various daily activities and traditional pastimes.

Emperor Meiji Pictures

Chikanobu also created prints showing Emperor Meiji in relaxed settings.

Contrast Pictures

Mitate-e, or "contrast prints," often compare old and new ideas, or show a modern scene in a traditional way.

Glorification of the Geisha

This type of print celebrates the beauty and grace of geisha, who were traditional Japanese entertainers.

Print Formats

Chikanobu mostly worked in the ōban tate-e format, which is a large print size that is taller than it is wide. He made many single prints and series in this format.

He also created some series in the ōban yoko-e format, which is a large print size that is wider than it is tall. These were often folded to be put into albums.

While he is famous for his triptychs (three-panel prints), he also made diptychs (two-panel prints) and a few polyptychs (prints with more than three panels).

You can also find his signature on drawings and illustrations in ehon (picture books), which were usually about history. He also designed uchiwa-e (fan prints) and sugoroku (a type of board game). In his later years, he made some kakemono-e, which are prints designed to be hung like scrolls.

See also

- List of works by Toyohara Chikanobu

- List of ukiyo-e terms

- War artist

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |