Matthew C. Perry facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Commodore

Matthew C. Perry

|

|

|---|---|

Perry c. 1856–1858

|

|

| Commander of the East India Squadron | |

| In office November 20, 1852 – September 6, 1854 |

|

| Preceded by | John H. Aulick |

| Succeeded by | Joel Abbot |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Matthew Calbraith Perry

April 10, 1794 Newport, Rhode Island, U.S. |

| Died | March 4, 1858 (aged 63) New York City, U.S. |

| Spouse |

Jane Slidell Perry

(m. 1814) |

| Children | 10 |

| Parents |

|

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1809–1858 |

| Rank | Commodore |

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars |

|

Matthew Calbraith Perry (born April 10, 1794 – died March 4, 1858) was an important officer in the United States Navy. He was known as a commodore, which was a high rank at the time. Perry led ships in several wars, including the War of 1812 and the Mexican–American War (1846–1848).

His most famous achievement was playing a key role in the opening of Japan to the Western world. This happened with the signing of the Convention of Kanagawa in 1854. Perry also believed strongly in educating naval officers. He helped create a system to train new sailors and supported the curriculum at the United States Naval Academy. He was also a big supporter of using steam engines in the Navy. Because of his efforts, he is often called "The Father of the Steam Navy" in the United States.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Matthew Perry was born on April 10, 1794, in South Kingstown, Rhode Island. His father, Christopher Raymond Perry, was a Navy Captain. His older brother was Oliver Hazard Perry, who also became a famous naval officer.

Matthew Perry joined the Navy in 1809 as a midshipman, which was a junior officer rank. He served on several ships. One of his early assignments was on the USS President, where he was an aide to Commodore John Rodgers.

During the War of 1812, Perry was on the USS President when it fought against a British ship, HMS Belvidera. Later in the war, his ship was blocked in port, so he didn't see much more fighting. After the war ended, Perry served in the Mediterranean Sea and helped fight against pirates and the slave trade in the West Indies.

Claiming Key West

From 1821 to 1825, Perry commanded a schooner (a type of sailing ship) called the USS Shark. In 1822, he sailed to Key West, an island off the coast of Florida. He officially claimed the Florida Keys as United States territory by raising the U.S. flag. This was important because Key West was a good location for a naval base.

Perry spent some years working at the New York Navy Yard (now the Brooklyn Navy Yard). He was promoted to captain at the end of this time.

Perry was very interested in naval education and believed the Navy needed to modernize. He helped create a training system for sailors and supported the development of the United States Naval Academy.

He was a strong supporter of using steam-powered ships. He oversaw the building of the Navy's second steam frigate, the USS Fulton. He commanded this ship and organized America's first group of naval engineers. He also started the first U.S. naval gunnery school. Because of his work with steamships, he earned the nickname "The Father of the Steam Navy."

Becoming a Commodore

In June 1840, Perry was given the title of commodore. At that time, the U.S. Navy didn't have ranks higher than captain. So, being a commodore was a very important position. Even though it was a temporary title for a specific command, officers who received it, like Perry, usually kept the title for life.

From 1843 to 1844, Perry commanded the Africa Squadron. Their job was to stop the slave trade, as agreed upon in the Webster–Ashburton Treaty.

Mexican–American War Service

In 1845, Perry became the second-in-command of the Home Squadron during the Mexican–American War. He captained the USS Mississippi. Perry helped capture the Mexican city of Frontera and took part in capturing Tampico in November 1846.

He later returned to the fleet and supported the Siege of Veracruz from the sea. After Veracruz fell, Perry moved against other Mexican port cities. He gathered a group of smaller ships, called the Mosquito Fleet, and captured Tuxpan in April 1847. In July 1847, he personally led a large landing force to attack Tabasco, defeating the Mexican forces and taking the city of San Juan Bautista.

Perry Expedition: Opening Japan (1852–1854)

In 1852, U.S. President Millard Fillmore gave Perry a special mission. He was to go to Japan and convince them to open their ports to American trade. If needed, he was allowed to use "gunboat diplomacy," which meant showing off naval power to get what he wanted.

At this time, Japan had a strict policy of national seclusion, meaning they had very limited contact with the outside world for over 250 years. The U.S. wanted to trade with Japan, needed places for American whaling ships to stop, and wanted coaling stations for their steamships. They also wanted to ensure the safe return of any shipwrecked American sailors, who were often imprisoned or executed in Japan.

Perry left Virginia in November 1852, commanding the East India Squadron. He made several stops along the way, including in China, where he got his official letters translated into Chinese and Dutch. He then sailed to the Ryukyu Islands (now Okinawa) and demanded that the kingdom open to trade with the United States.

First Visit to Japan (1853)

On July 8, 1853, Perry's fleet arrived at Uraga, at the entrance to Edo Bay. He used his knowledge of Japanese culture to make a strong impression. He ordered his ships to steam past Japanese lines towards the capital city of Edo and point their guns towards Uraga. Perry refused to leave or go to Nagasaki, which was the only port open to foreigners.

To show his power, Perry presented the Japanese with a white flag and a letter that warned them of destruction if they chose to fight. He also fired blank shots from his 73 cannons, claiming it was a celebration of American Independence Day. His ships had powerful new cannons that could cause great damage. He also started surveying the coastline, even though Japanese officials objected.

The Japanese government was unsure how to handle this situation. On July 14, 1853, Perry was allowed to land at Kurihama. After giving his letter to the Japanese delegates, Perry left for Hong Kong. He promised to return the next year for their answer.

Second Visit to Japan (1854)

On his way back to Japan, Perry stopped in Formosa (now Taiwan) and explored its coal deposits. He thought Formosa could be a good trading location and a base for the U.S. to prevent European countries from controlling major trade routes. However, the U.S. government did not act on his suggestion to claim Formosa.

Perry returned to Japan on February 13, 1854, much sooner than he had promised. This time, he brought ten ships and 1,600 men, putting even more pressure on the Japanese. After some initial resistance, Perry was allowed to land at Kanagawa on March 8.

On March 31, the Convention of Kanagawa was signed. This treaty opened two Japanese ports, Hakodate and Shimoda, to American ships. Perry signed for the United States, and Hayashi Akira signed for Japan. Perry mistakenly believed he had signed with representatives of the Emperor, not fully understanding that the shōgun was the real ruler of Japan at the time.

Return to the United States

When Perry returned to the United States, Congress gave him a reward of $20,000 for his work in Japan. He used some of this money to write and publish a three-volume report about his expedition, called Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan. He was later promoted to rear admiral on the retired list because of his important service.

Later Years

In his later years, Perry's health declined. He suffered from severe arthritis, which caused him a lot of pain. He spent his last years finishing his report on the Japan expedition. Matthew Perry died on March 4, 1858, in New York City, from a heart condition caused by rheumatic fever.

He was first buried in New York City, but his remains were later moved to the Island Cemetery in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1866. An impressive monument was placed over his grave by his widow in 1873.

Family Life

Matthew Perry was married to Jane Slidell Perry on December 24, 1814. They had ten children together. His wife was the sister of U.S. Senator John Slidell.

Perry's Legacy

Matthew Perry is a very important figure in Japanese history. About 90% of schoolchildren in Japan can identify him. He was responsible for starting a "firm, lasting, and sincere friendship" between the United States and Japan.

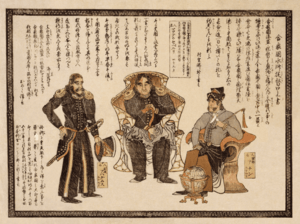

In the U.S., Perry was seen as a respected and authoritative figure. However, Japanese woodblock prints from the time often showed him with exaggerated features, making him look stern or even demonic. These images reflected the Japanese fear and dislike of Western influence and the control Perry was trying to gain over Japan.

A replica of Perry's U.S. flag is displayed on the USS Missouri memorial in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The original flag was brought to Japan for the surrender ceremony that ended World War II. Today, the original flag is preserved and displayed at the Naval Academy Museum in Annapolis, Maryland.

Memorials to Perry

Japan built a monument to Perry on July 14, 1901, at the exact spot where he first landed. This monument is now the center of a small park called Perry Park in Yokosuka, Japan. The park also has a small museum about the events of 1854. There is also a Matthew C. Perry Elementary and High School at Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni.

In his birthplace of Newport, Rhode Island, there is a memorial plaque and a statue of Perry in Touro Park. The statue was designed by John Quincy Adams Ward and dedicated in 1869 by Perry's daughter.

The U.S. Navy's Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigate ships, built in the 1970s and 1980s, were named after Perry's brother, Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry. The ninth ship of the Lewis and Clark class class, a type of supply ship, is named USNS Matthew Perry.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Matthew C. Perry para niños

In Spanish: Matthew C. Perry para niños