Bakumatsu facts for kids

|

|---|

|

The Bakumatsu (meaning "End of the bakufu") was the final period of Japan's Edo period. It was a time when the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate came to an end. This era lasted from 1853 to 1867. During these years, Japan faced strong pressure from foreign countries. This led Japan to stop its isolationist foreign policy, called sakoku. Japan then changed from a feudal system under the Tokugawa shogunate to a modern empire during the Meiji era.

A big disagreement during this time was between those who supported the Emperor, called ishin shishi, and the forces loyal to the shogun. The shogun's forces included skilled swordsmen known as shinsengumi. Besides these main groups, many others tried to gain power during this chaotic time. There were also two other important reasons for unrest. First, some powerful lords, called tozama daimyō, felt angry because they had been kept out of important government jobs for a long time. Second, many Japanese people disliked Westerners after Matthew C. Perry arrived. This feeling was summed up in the phrase sonnō jōi, which meant "revere the Emperor, expel the barbarians." The major turning point of the Bakumatsu was the Boshin War and the Battle of Toba–Fushimi, where the shogun's supporters were defeated.

Contents

Japan's Early Encounters with Foreigners

Dealing with Western Ships

From the early 1800s, Japan started to take steps to protect itself from foreign ships. Western ships, especially those involved in whaling and trade with China, were appearing more often near Japan. They hoped Japan could become a supply base or at least help shipwrecked sailors.

A big shock for the Tokugawa government happened in 1808. A British warship, HMS Phaeton, entered Nagasaki Harbour and demanded supplies. This made the government order even stricter port security. In 1825, the shogun issued a rule called the Edict to expel foreigners. This rule completely banned any contact with foreigners and stayed in place until 1842.

Meanwhile, Japan tried to learn about Western science through rangaku (meaning "Western studies"). To better repel Westerners, some Japanese, like Takashima Shūhan in Nagasaki, managed to get weapons from the Dutch at Dejima. These weapons included cannons and firearms. Many lords sent students to Nagasaki to learn from Takashima. This happened after an American warship entered Kagoshima Bay in 1837. Lords from Satsuma Domain, Saga Domain, and Chōshū Domain, all in the south and more exposed to Western ships, also studied how to make Western weapons. By 1852, Satsuma and Saga had special furnaces to produce the iron needed for guns.

After the Morrison incident in 1837, where an American ship was turned away, Egawa Hidetatsu was put in charge of defending Tokyo Bay. After China's defeats in the First Opium War and Second Opium War, many Japanese leaders realized their old ways of fighting would not work against Western powers. To deal with Westerners as equals, they studied Western guns. Takashima Shūhan even showed the Tokugawa government how these weapons worked in 1841.

There was a big debate in Japan about how to avoid foreign invasions. Some, like Egawa, believed Japan needed to use Western techniques to fight them off. Others, like Torii Yōzō, argued that only traditional Japanese methods should be used. Egawa pointed out that Confucianism and Buddhism had come from abroad, so it made sense to adopt useful Western techniques too. Later, thinkers like Sakuma Shōzan and Yokoi Shōnan suggested combining "Western knowledge" with "Eastern morality" to "control the barbarians with their own methods."

However, after 1839, those who favored traditional ways often won the debates. Students of Western sciences were sometimes accused of treason. Some were put under house arrest, forced to take their own lives, or even killed, like Sakuma Shōzan.

-

The American merchant ship Morrison was turned away from Edo Bay in 1837.

Perry's Arrival (1853–1854)

When Commodore Matthew C. Perry arrived in Edo Bay with his four ships in July 1853, the shogun's government was in chaos. Perry was ready to fight if his talks with the Japanese failed. He even threatened to open fire if they refused to negotiate. He gave them two white flags, telling them to raise them if they wanted his fleet to stop firing and surrender. To show how powerful his weapons were, Perry ordered his ships to attack some buildings near the harbor. Perry's ships had new Paixhans shell guns, which could destroy buildings with explosive shells.

Big Earthquakes

The years 1854 and 1855 saw many strong earthquakes, known as the Ansei great earthquakes. Over a period of less than two years, 120 large and small tremors were recorded. These included a huge 8.4 magnitude earthquake on December 23, 1854, and another 8.4 magnitude earthquake the next day. A 6.9 magnitude earthquake hit what is now Tokyo on November 11, 1855.

Shimoda, a port that was just chosen for a US consulate, was hit by an earthquake and a tsunami. Some people thought these natural disasters showed the gods were angry. Many Japanese blamed the earthquakes on a giant catfish (Namazu) thrashing around. Pictures of namazu became very popular at this time.

Treaties with Foreign Nations

After Townsend Harris became the U.S. Consul in 1856, he spent two years negotiating. The Treaty of Amity and Commerce was signed in 1858 and began in mid-1859. During the talks, Harris convinced the Japanese that this was the best deal any Western country would offer.

The most important parts of the Treaty were:

- Japan and the U.S. would exchange diplomats.

- The ports of Edo, Kobe, Nagasaki, Niigata, and Yokohama would open for foreign trade.

- U.S. citizens could live and trade freely in these ports.

- A system called extraterritoriality meant foreign residents would follow their own country's laws, not Japanese laws.

- Import and export taxes were set low and controlled by international agreements.

- Japan could buy American ships and weapons. (Three American steamships were delivered to Japan in 1862.)

Japan also had to give the United States any special conditions it gave to other foreign nations in the future. This was called the "most favored nation" rule. Soon, several other countries signed similar treaties with Japan. These were called the Ansei Five-Power Treaties. They included treaties with the Netherlands, Russia, the United Kingdom, and France in 1858.

Trading companies quickly set up businesses in the newly opened ports.

-

A view of Yokohama in 1859.

Time of Crisis

Economic Problems

Opening Japan to uncontrolled foreign trade caused huge economic problems. While some people became rich, many others lost everything. Unemployment went up, and so did inflation (prices rising). At the same time, major famines made food prices go up even more. There were also many incidents between rude foreigners and Japanese people.

Japan's money system, based on Tokugawa coinage, also broke down. Japan's gold-to-silver exchange rate was 1:5, but international rates were around 1:15. This meant foreigners bought huge amounts of gold in Japan. This forced Japanese authorities to lower the value of their money. A lot of gold left Japan as foreigners quickly exchanged their silver for Japanese silver coins, and then exchanged those for gold, making a 200% profit. In 1860, about 70 tons of gold left Japan. This destroyed Japan's gold standard system. The government had to reduce the gold content of its coins to match international rates.

Foreigners also brought cholera to Japan, which caused hundreds of thousands of deaths.

-

A picture showing inflation and rising prices during the Bakumatsu era.

Political and Social Troubles

Hotta Masayoshi, a key official, lost the support of important lords. When Tokugawa Nariaki opposed the new treaty, Hotta asked the Emperor for approval. The Emperor's officials, seeing the shogun's weakness, refused Hotta's request. This suddenly brought the Emperor and Kyoto into Japan's politics for the first time in centuries. When the shogun died without a child to take his place, Nariaki asked the Emperor to support his own son, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, to become shogun. Yoshinobu was a reform-minded candidate favored by some powerful lords. However, the shogun's loyal officials won the power struggle. They installed 12-year-old Tokugawa Iemochi as shogun, believing that Ii Naosuke would control him. Nariaki and Yoshinobu were put under house arrest, and Yoshida Shōin, a leader who opposed the American treaty, was executed. This event was known as the Ansei Purge.

Ii Naosuke, who had signed the Harris Treaty and tried to stop opposition to Western ways, was himself killed in March 1860 in the Sakuradamon incident. Foreigners were often attacked. In January 1861, Henry Heusken, an American diplomat's secretary, was murdered. In July 1861, samurai attacked the British Legation, killing two people. During this time, about one foreigner was killed every month. The Richardson Affair in September 1862 forced foreign nations to act to protect their citizens. In May 1863, the US legation in Edo was burned down.

In the 1860s, peasant uprisings and city riots increased. A "World renewal" movement appeared, along with religious festivals and protests like the Eejanaika.

From 1859, the ports of Nagasaki, Hakodate, and Yokohama opened to foreign traders because of the treaties. Many foreigners arrived in Yokohama and Kanagawa, causing trouble with the samurai. Violence against foreigners and Japanese who worked with them grew. Murders of foreigners and Japanese helpers soon followed. In August 1859, a Russian sailor was killed in Yokohama. In early 1860, two Dutch captains were also killed in Yokohama. Chinese and Japanese servants of foreigners were also murdered.

-

The killing of Ii Naosuke in the Sakuradamon incident (1860).

Efforts to Change the Treaties

The shogun's government sent several groups abroad to try and change the trade treaties. However, these efforts mostly failed. A Japanese Embassy went to the United States in 1860. A First Japanese Embassy went to Europe in 1862. A Second Japanese Embassy was sent in December 1863. Their goal was to get European support to close Japan to foreign trade again, especially to stop foreigners from using the port of Yokohama. This embassy completely failed because European powers saw no benefit in agreeing to Japan's demands.

-

Members of the First Japanese Embassy to Europe (1862) visiting the 1862 International Exhibition in London.

"Revere the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians" (1863–1866)

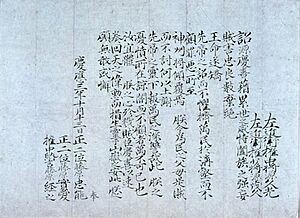

Strong opposition to Western influence turned into open conflict when Emperor Kōmei broke with centuries of tradition. He started to take an active role in state matters. On March 11 and April 11, 1863, he issued his Order to expel barbarians.

The Mōri clan of Chōshū, led by Lord Mōri Takachika, followed this order. They began to act to expel all foreigners by the deadline of May 10 (Lunar calendar). Openly defying the shogun, Mōri ordered his forces to fire without warning on any foreign ships passing through Shimonoseki Strait.

Under pressure from the Emperor, the Shogun also had to announce an end to relations with foreigners. This order was sent to foreign embassies on June 24, 1863.

Edward Neale, the head of the British Legation, responded very strongly. He said this move was like a declaration of war by Japan against all treaty powers. He warned of severe punishment if it wasn't stopped.

-

Japanese cannons firing on foreign ships at Shimonoseki in 1863.

Foreign Military Actions

American influence, which was very important at first, decreased after 1861. This was because of the American Civil War (1861–1865), which used up all of America's resources. British, Dutch, and French influence then grew.

The two main groups opposing the shogun were from the Satsuma (now Kagoshima prefecture) and Chōshū (now Yamaguchi prefecture) provinces. These were two of the strongest anti-shogun domains in Japan. Satsuma military leaders Saigō Takamori and Okubo Toshimichi joined forces with Katsura Kogoro of Chōshū, thanks to the efforts of Sakamoto Ryōma. Since Satsuma was involved in the murder of Richardson, and Chōshū in the attacks on foreign ships in Shimonoseki, and the shogun's government said it couldn't control them, Allied forces decided to take direct military action.

On July 16, 1863, the U.S. warship USS Wyoming entered the strait. It fought the Choshu fleet for almost two hours. The Wyoming sank one Japanese ship and badly damaged two others, causing about forty Japanese casualties. The Wyoming itself was also heavily damaged.

Two weeks after the Wyoming's battle, a French force of two warships and 250 men attacked Shimonoseki. They destroyed a small town and at least one cannon position.

In August 1863, the Bombardment of Kagoshima happened. This was in response to the Namamugi incident and the murder of an English trader named Richardson. The Royal Navy bombarded Kagoshima and sank several ships. Satsuma later negotiated and paid 25,000 pounds. They did not hand over Richardson's killers. In return, Great Britain agreed to supply steam warships to Satsuma. This conflict actually started a close relationship between Satsuma and Great Britain. They became major allies in the later Boshin War. Satsuma had generally supported opening and modernizing Japan. The Namamugi Incident was seen as an unfortunate event, not typical of Satsuma's policy. It was used as an example of anti-foreign sentiment to justify a strong Western show of force.

-

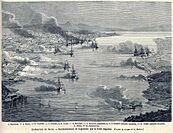

A bird's-eye view of the bombardment of Kagoshima by the Royal Navy, August 15, 1863.

-

Early talks between the Bakufu and the British.

Naval forces from Great Britain, France, the Netherlands, and the United States planned a military response to Japanese violence against their citizens. This led to the Bombardment of Shimonoseki. The Allied attack happened in September 1864. The naval forces of the four nations combined against the powerful lord Mōri Takachika of the Chōshū Domain in Shimonoseki. This conflict was difficult for America, which was fighting its American Civil War in 1864.

-

The Bombardment of Shimonoseki, 1863–1864.

-

French Navy troops taking Japanese cannons at Shimonoseki.

After these victories against the anti-foreign movement in Japan, the shogun's government regained some power by the end of 1864. The traditional policy of sankin-kōtai (where lords had to spend time in Edo) was brought back. Rebellions from 1863–64 and the Shishi movement were harshly put down across the country.

The military actions by foreign powers also showed that Japan was no match for the Allied forces. The sonnō jōi movement lost its original strength. However, the shogun's government still had weaknesses. The focus of opposition then shifted to creating a strong government under a single ruler.

Mito Rebellion

On May 2, 1864, the Mito rebellion broke out. It was against the shogun's power and supported the sonnō jōi idea. The shogun's government sent an army to stop the revolt, which ended with the rebels surrendering on January 14, 1865.

First Chōshū Expedition

In the Kinmon Incident on August 20, 1864, troops from Chōshū Domain tried to take control of Kyoto and the Imperial Palace. They wanted to push for the Sonnō Jōi goal. This also led to a punishment expedition by the Tokugawa government, called the First Chōshū expedition.

The shogun's government couldn't pay the $3,000,000 demanded by foreign nations for the Shimonoseki attack. So, foreign nations agreed to lower the amount. In return, they wanted the Emperor to approve the Harris Treaty, lower customs taxes to a flat 5%, and open the ports of Hyōgo (modern Kōbe) and Osaka to foreign trade. To push their demands harder, a squadron of warships from Britain, the Netherlands, and France was sent to Hyōgo in November 1865. Other shows of force were made by foreign powers. Finally, the Emperor agreed to change his complete opposition to the treaties. He formally allowed the shogun to handle talks with foreign powers. An agreement to revise the tariffs was signed in June 1866.

These conflicts made Japan realize that fighting Western nations directly was not the answer. As the shogun's government continued to modernize, Western lords (especially from Satsuma and Chōshū) also worked hard to modernize. They wanted to build a stronger Japan and create a more rightful government under the Emperor.

Second Chōshū Expedition

The shogun's government led a second punishment expedition against Chōshū starting in June 1866. But the shogun's forces were defeated by Chōshū's more modern and better organized troops. The new shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, managed to arrange a ceasefire because the previous shogun had died. However, the shogun's reputation was greatly damaged.

This defeat encouraged the shogun's government to take big steps towards modernization.

The End of the Tokugawa Shogunate (1867–1869)

Modernization Efforts

In the final years of the shogun's rule, the government took strong actions to try and regain its power. However, its efforts to modernize and deal with foreign powers made it a target of anti-Western feelings across the country.

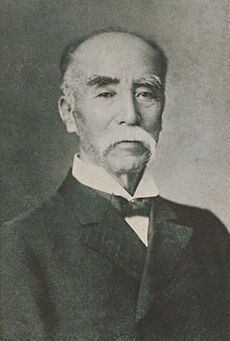

Japanese naval students were sent to study in Western naval schools for several years. This started a tradition of future leaders being educated abroad, like Admiral Enomoto Takeaki. A French naval engineer, Léonce Verny, was hired to build naval shipyards, such as those in Yokosuka and Nagasaki. By the end of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1868, the shogun's navy already had eight Western-style steam warships. Their main ship was the Kaiyō Maru. These ships were used against the Emperor's forces during the Boshin War, under the command of Admiral Enomoto. A French Military Mission was also sent to Japan to help modernize the shogun's armies. Japan even sent a group to and took part in the 1867 World Fair in Paris.

Tokugawa Yoshinobu (also known as Keiki) reluctantly became the head of the Tokugawa family and shogun after Tokugawa Iemochi died unexpectedly in mid-1866. In 1867, Emperor Kōmei died and his second son, Mutsuhito, became Emperor Meiji. Tokugawa Yoshinobu tried to reorganize the government under the Emperor while keeping the shogun's leading role. This system was known as kōbu gattai. Fearing the growing power of the Satsuma and Chōshū lords, other lords called for the shogun's political power to be returned to the Emperor. They also wanted a council of lords led by the former Tokugawa shogun. With the threat of military action from Satsuma and Chōshū, Yoshinobu acted first by giving up some of his authority.

Boshin War

After Keiki had temporarily avoided the growing conflict, anti-shogun forces caused widespread trouble in the streets of Edo using groups of masterless samurai (rōnin). Satsuma and Chōshū forces then moved strongly into Kyoto. They pressured the Imperial Court for a final order to destroy the shogunate. After a meeting of lords, the Imperial Court issued such an order, taking away the shogun's power in late 1867. However, the Satsuma, Chōshū, and other domain leaders, along with radical court officials, rebelled. They seized the imperial palace and announced their own restoration on January 3, 1868. Keiki formally accepted the plan, leaving the Imperial Court for Osaka and resigning as shogun. Fearing that the shogun was only pretending to give up power to gain more, the dispute continued. It led to a military fight between Tokugawa and allied domains against Satsuma, Tosa, and Chōshū forces in Fushimi and Toba. When the battle turned against the shogun's forces, Keiki left Osaka for Edo. This basically ended both the power of the Tokugawa family and the shogunate that had ruled Japan for over 250 years.

After the Boshin War (1868–1869), the shogun's government was abolished. Keiki was reduced to the rank of a common lord. Resistance continued in the North throughout 1868. The shogun's naval forces under Admiral Enomoto Takeaki continued to hold out for another six months in Hokkaidō. There, they founded the short-lived Republic of Ezo. This defiance ended in May 1869 at the Battle of Hakodate, after one month of fighting.

Images for kids

-

Samurai of the Shimazu clan

See also

Shoguns

Daimyōs (Lords)

- Tokugawa Nariaki

- Ii Naosuke

- Kuroda Nagahiro

- Date Munenari

- Matsudaira Yoshinaga

- Yamauchi Toyoshige

- Shimazu Nariakira

- Hachisuka Narihiro

- Hotta Masayoshi

Matsudaira Yoshinaga, Date Munenari, Yamauchi Toyoshige and Shimazu Nariakira are together known as Bakumatsu no Shikenkō (Four Wise Lords of Bakumatsu).

Other Important People

- Matsudaira Katamori

- Ōmura Masujirō

- Sakamoto Ryōma

- Kondō Isami

- Hijikata Toshizō

- Takasugi Shinsaku

- Saigō Takamori

- Yoshida Shōin

- Katsura Kogorō

- Four Hitokiri of the Bakumatsu

- Katsu Kaishu

- Okita Sōji

- Hayashi Akira

- Kawakami Gensai (a famous assassin during this time)

- Takano Chōei – A scholar of Western studies

- Iinuma Sadakichi

Foreign Observers:

- Ernest Mason Satow in Japan 1862–69

- Edward and Henry Schnell

- Robert Bruce Van Valkenburgh, American diplomat

- Matthew C. Perry

- Joel Abbot

International Relations

- Gaikoku bugyō

- Franco-Japanese relations

- Anglo-Japanese relations

- German-Japanese relations

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |