Nanban trade facts for kids

|

|---|

|

The Nanban trade (南蛮貿易 (Nanban bōeki, "Southern barbarian trade")) was a special time in Japanese history. It started in 1543 when the first Europeans arrived in Japan. This period lasted until 1614, when Japan began to close itself off from the rest of the world. The word Nanban (南蛮) means "Southern barbarian." For a long time, the Japanese used this word for people from places like Southern China, the Ryukyu Islands, and Southeast Asia. For example, in 997, pirates from the Amami Islands were called Nanban when they attacked parts of Japan.

The Nanban trade really began when Portuguese explorers, missionaries, and merchants came to Japan during the Sengoku period (Warring States period). They set up long-distance trade routes across the seas. This led to a big exchange of technology and culture. Japan learned about new things like matchlock firearms, cannons, and how to build large galleon ships. Christianity was also introduced during this time. The Nanban trade started to slow down in the early Edo period. This was because the new government, the Tokugawa Shogunate, worried about the growing influence of Christianity, especially Roman Catholicism from the Portuguese. The Tokugawa government then created rules called Sakoku policies. These rules gradually isolated Japan from the outside world. European trade was limited to only Dutch traders on a small island called Dejima.

Contents

First Meetings with Europeans

How Japanese Saw Europeans

After the Portuguese arrived on Tanegashima island in 1543, the Japanese were quite careful around these new foreigners. It was a big culture shock for both sides. Europeans found it hard to understand the Japanese writing system. They also were not used to using chopsticks.

One Japanese account said about the Europeans:

They eat with their fingers instead of with chopsticks such as we use. They show their feelings without any self-control. They cannot understand the meaning of written characters.

How Europeans Saw Japan

The first detailed report by a European about Japan was by Luís Fróis. He wrote about Japanese life, including how men and women lived, what children did, Japanese food, weapons, and even their houses and gardens.

Later, when the Japanese samurai Hasekura Tsunenaga visited Europe in 1615, Europeans were fascinated by his customs. They noted things like:

- "They never touch food with their fingers, but instead use two small sticks that they hold with three fingers." (This refers to chopsticks.)

- "They blow their noses in soft silky papers... which they never use twice." (This describes Japanese tissue paper.)

- "Their Scimitar-like swords and daggers cut so well that they can cut a soft paper just by putting it on the edge and by blowing on it."

Europeans in the Renaissance period were very interested in Japan's wealth. They heard stories from Marco Polo about golden temples. Japan also had many precious metals like copper and silver. During this time, Japan became a major exporter of silver. At one point, about one-third of the world's silver came from Japan.

Early European visitors also noticed the excellent quality of Japanese craftsmanship and metalwork. Japanese blades and swords were known for being very good quality and having artistic value.

Portuguese Trade in the 16th Century

The Portuguese had been trading with China since 1514. After they first landed in Japan, trade began between Malacca, China, and Japan. The Chinese Emperor had stopped trade with Japan because of pirate attacks. This meant Chinese goods were hard to find in Japan. So, the Portuguese saw a great chance to make money by trading between China and Japan.

At first, anyone could trade with Japan. But in 1550, the Portuguese King made it a monopoly. This meant only one person, a fidalgo (a nobleman), was allowed to trade with Japan each year. This person was called the "captain-major of the voyage to Japan." They had special powers and could even sell their trading rights to someone else if they didn't have enough money. Their ship would sail from Goa, stop in Malacca and China, and then go to Japan and back.

In 1557, the Portuguese set up Macau to help with this trade. Japan was in a civil war, which was good for the Portuguese. Each Japanese lord wanted to attract trade to their land. They offered better conditions to the traders. In 1571, the fishing village of Nagasaki became the main port for the Portuguese. In 1580, the lord of Nagasaki, Omura Sumitada, who was the first Japanese lord to become Christian, gave the city to the Jesuits forever. Nagasaki grew from a small village into a busy, diverse city, and most of its people became Christian. It even got a painting school, a hospital, and a Jesuit college.

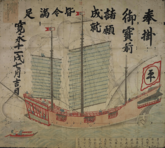

Trading Ships

The most famous ships used for trade between Goa and Japan were Portuguese carracks. These ships were slow but very large. They could carry a lot of goods and supplies for long, dangerous journeys. These ships were some of the biggest in the world at the time. They were often two or three times larger than common galleons. Many were built in India using strong Indian teakwood. Their quality was so good that the Spanish in Manila preferred Portuguese-built ships.

The Portuguese called these ships the nau da prata ("silver carrack") or nau do trato ("trade carrack"). The Japanese called them kurofune, meaning "black ships," because their hulls were painted black with pitch to make them waterproof. Later, this name was also used for Matthew C. Perry's black warships that reopened Japan in 1853.

After 1618, the Portuguese started using smaller, faster ships like pinnaces and galliots. This helped them avoid being attacked by Dutch raiders.

Goods Traded

The most valuable goods traded were Chinese silks for Japanese silver. The silver was then used in China to buy more silk. It's estimated that about half of Japan's yearly silver production was exported. This was about 18 to 20 tons of silver each year.

Many other items were also traded. These included gold, Chinese porcelain, and musk. From Europe, they brought items like Flemish clocks, Venetian glass, Portuguese wine, and rapiers. In return, Japan exported copper, lacquerware, and weapons. Japanese lacquerware was very popular with European nobles and missionaries. They even asked for Western-style chests and church furniture made with Japanese lacquer.

Japanese people captured in battles were sometimes sold by their own countrymen to the Portuguese as slaves. Also, some Japanese families sold their own members if they couldn't afford to support them during the civil war. These enslaved Japanese were valued for their skills and bravery. Some ended up in India or even Europe.

In 1571, King Sebastian of Portugal banned the enslavement of Chinese and Japanese people. He likely worried it would harm efforts to spread Christianity and affect trade. Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a powerful ruler in Japan, also stopped the enslavement of Japanese people starting in 1587. However, Hideyoshi later sold Korean prisoners of war, captured during his invasions of Korea, as slaves to the Portuguese.

The trade with Japan was very profitable. A captain-major who invested 20,000 cruzados could expect to make 150,000 cruzados in profit. The total value of Portuguese exports from Nagasaki in the 16th century was over 1,000,000 cruzados.

After 1600, other European nations like Spain, the Dutch, and the English tried to challenge Portugal's trade monopoly. However, Portugal had special access to Chinese markets through Macau, which made them hard to replace. The Portuguese were finally banned from Japan in 1638 after the Shimabara Rebellion. The Japanese believed the Portuguese were smuggling priests into the country.

Dutch Trade

The Dutch were called "Kōmō" (紅毛 (Red Hair)) by the Japanese. They first arrived in Japan in 1600 on a ship called the Liefde. Their pilot was William Adams, the first Englishman to reach Japan.

In 1609, a Dutchman named Jacques Specx arrived with two ships in Hirado. With Adams' help, he gained trading rights from Tokugawa Ieyasu, the new ruler of Japan.

The Dutch also fought against Portuguese and Spanish ships in the Pacific. Eventually, after 1639, they became the only Westerners allowed to trade with Japan. They were limited to a small trading post on the island of Dejima for the next two centuries.

New Technologies and Culture

The Japanese learned about many new technologies and cultural practices from the Europeans. Europeans also learned from the Japanese, which later led to a style called Japonisme. New things included military items like the arquebus (a type of gun), cannon, European-style armor, and ship designs like galleons. Christianity was also introduced. There were also changes in decorative art, language, and food. The Portuguese introduced tempura and European-style sweets. These sweets were called nanbangashi (南蛮菓子), or "southern barbarian confectionery." Examples include castella (a sponge cake), konpeitō (sugar candy), and bisukauto (biscuits). Other goods brought by Europeans included clocks, soap, and tobacco.

Tanegashima Guns

The Japanese were very interested in Portuguese hand-held guns. The first two Europeans to reach Japan in 1543 were Portuguese traders. They arrived on a Chinese ship at the southern island of Tanegashima and brought guns for trade. The Japanese already knew about gunpowder weapons from China. They had been using basic Chinese guns and cannons for about 270 years. However, the Portuguese guns were lighter, had a special firing system called a matchlock, and were easy to aim. Because these firearms were introduced on Tanegashima, the arquebus became known as Tanegashima in Japan. At that time, Japan was in the middle of a civil war called the Sengoku period.

Within a year, Japanese metalworkers learned how to copy the matchlock system. They began to mass-produce the Portuguese guns. Early problems were fixed with help from Portuguese blacksmiths. The Japanese quickly found ways to make their guns better. They even developed larger guns and ammunition to make them more deadly. Just fifty years later, Japanese armies had more guns than any European army at the time.

Oda Nobunaga, a powerful leader who started to unite Japan, used guns a lot. This was shown in the Battle of Nagashino, which was even featured in the movie Kagemusha. Guns were also very important for the unification efforts of Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu. They were also used in the invasions of Korea in 1592 and 1597.

Red Seal Ships

European ships, especially galleons, greatly influenced Japanese shipbuilding. This encouraged many Japanese voyages abroad.

The Japanese government created a system for licensed trading ships called red seal ships (朱印船, shuinsen). These ships sailed across East and Southeast Asia for trade. They used many parts of galleon design, like sails, rudders, and how cannons were placed. These ships brought many Japanese traders and adventurers to Southeast Asian ports. Some became very important in local affairs, like Yamada Nagamasa in Siam.

By the early 1600s, the Japanese government had built several ships using purely Nanban designs. They often had help from foreign experts. One example is the galleon San Juan Bautista, which crossed the Pacific Ocean twice on trips to Mexico.

Catholicism in Japan

When the leading Jesuit Francis Xavier arrived in 1549, Catholicism slowly grew into a major religion in Japan. At first, the acceptance of Western "padres" (priests) was linked to trade. By the end of the 16th century, about 200,000 people had converted to Catholicism, mostly on the southern island of Kyūshū. The Jesuits even gained control over the trading city of Nagasaki.

The powerful leader Toyotomi Hideyoshi first reacted in 1587. He announced that Christianity was forbidden and ordered all priests to leave. However, this order was not fully followed. Most Jesuits stayed in Japan and continued their work. Hideyoshi wrote:

- "1. Japan is a country of the Gods, and for the padres to come hither and preach a devilish law, is a reprehensible and devilish thing ...

- 2. For the padres to come to Japan and convert people to their creed, destroying Shinto and Buddhist temples to this end, is a hitherto unseen and unheard-of thing ... to stir the canaille to commit outrages of this sort is something deserving of severe punishment."

Hideyoshi's actions against Christianity became stronger in 1597. This happened after the Spanish galleon San Felipe was shipwrecked in Japan. This event led to the crucifixion of twenty-six Christians in Nagasaki on February 5, 1597. It seems Hideyoshi made this decision because the Jesuits encouraged him to expel rival religious orders. He was also told by the Spanish that military conquest often followed Catholic missionary work. He also wanted to take the ship's cargo. Although nearly a hundred churches were destroyed, most Jesuits remained in Japan.

The final ban came from Tokugawa Ieyasu in 1614. He firmly forbade Christianity, which forced Jesuits to work in secret. Some even joined a revolt by Toyotomi Hideyori in the siege of Osaka (1614–1615). The persecution of Catholics became very harsh after Ieyasu died in 1616. About 2,000 Christians were tortured and killed. The remaining 200,000 to 300,000 Christians were forced to give up their faith. The last major Christian uprising in Japan was the Shimabara rebellion in 1637. After this, Catholicism in Japan went underground, with followers known as "Hidden Christians."

Other Nanban Influences

The Nanban also brought other influences:

- Nanbandō (南蛮胴) is a type of armor that covers the body in one piece, a design from Europe.

- Nanbanbijutsu (南蛮美術) describes Japanese art with Nanban themes or designs.

- Nanbanga (南蛮画) refers to paintings of the new foreigners and is a style in Japanese art.

- Nanbannuri (南蛮塗り) describes lacquerware decorated in the Portuguese style, which was very popular.

- Namban-ryōri (南蛮料理) refers to dishes using ingredients introduced by the Portuguese and Spanish, like Spanish pepper or pumpkin. It also includes cooking methods like deep-frying (e.g., tempura).

- Nanbangashi (南蛮菓子) is a type of sweet from Portuguese or Spanish recipes. Popular ones are "Kasutera" (カステラ), named after Castile, and "Konpeitō" (金平糖 こんぺいとう), from the Portuguese word for "sugar candy."

- Nanbanji or Nanbandera (南蛮寺) was the first Christian church in Kyoto. It was built by the Jesuit Padre Gnecchi-Soldo Organtino in 1576 with support from Oda Nobunaga. It was destroyed by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in 1587.

- Nanbanzuke (南蛮漬) is a dish of fried fish marinated in vinegar, similar to a Portuguese dish called escabeche.

- Namban-ryū geka (南蛮流外科) was a Japanese "Southern Barbarian-style surgery." It used some wound plasters and ingredients like palm oil and tobacco from the Portuguese.

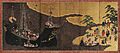

- Namban-byōbu (南蛮屏風), or "Southern Barbarian screens," are multi-panel screens. They often show a Portuguese ship arriving and foreigners walking through the port city.

- Chikin nanban (チキン南蛮) is a dish of fried chicken dipped in a vinegary sauce, similar to nanbanzuke. It's served with tartar sauce and is popular in Japan today.

Language Exchange

The close contact with the "southern barbarians" also influenced the Japanese language. Some words from Portuguese and Dutch are still used today:

- pan (パン, from pão, meaning bread)

- tempura (天ぷら, from tempero, meaning seasoning)

- botan (ボタン, from botão, meaning button)

- karuta (カルタ, from cartas de jogar, meaning playing cards)

- tabako (タバコ, from tabaco, meaning tobacco)

Some words are now only used in old texts or for historical reasons. For example, kirishitan (キリシタン, from christão, meaning Christian) or shabon (シャボン, from sabão, meaning soap).

End of Nanban Exchanges

After Japan was united by Tokugawa Ieyasu in 1603, the country slowly closed itself off from the outside world. This was mainly because of the growth of Christianity.

In 1639, trade with Portugal was completely forbidden. The Netherlands became the only European nation allowed in Japan. By 1650, except for the Dutch trading post on Dejima island in Nagasaki, foreigners faced the death penalty. Christians were also persecuted. Guns were almost completely removed from use, and people went back to using swords. Traveling abroad and building large ships were also forbidden. This began a period of isolation, peace, and progress known as the Edo period.

The "barbarians" would return about 250 years later. By then, they were much stronger due to industrialization. In 1854, an American military fleet led by Commodore Matthew C. Perry forced Japan to reopen for trade, ending its long isolation.

Meanings of the Word "Nanban"

Nanban is a Japanese word that comes from the Chinese term Nánmán. It originally referred to people from South and Southeast Asia. The Japanese started using Nanban in a new way when the first Portuguese arrived in 1543. Later, it was used for other Europeans who came to Japan. The term Nanban comes from an old Chinese idea of "Four Barbarians" from the 3rd century.

Strictly speaking, Nanban meant "Portuguese or Spanish" because they were the most common Westerners in Japan. Other Westerners were sometimes called "紅毛人" (Kō-mōjin), meaning "red-haired people." However, Nanban was more widely used.

Later, Japan decided to adopt Western ways to better resist Western powers. They stopped seeing the West as uncivilized. Words like "Yōfu" (洋風 "western style") and "Ōbeifu" (欧米風 "European-American style") replaced "Nanban" in most uses.

Today, the word "Nanban" is mostly used when talking about history. It is seen as a charming and old-fashioned term. It can sometimes be used playfully to refer to Western people or culture in a polite way.

One area where Nanban is still used is in cooking. Nanban dishes are not American or European. They are a unique mix that doesn't use soy sauce or miso. Instead, they use curry powder and vinegar for flavor. This is because when Portuguese and Spanish dishes came to Japan, dishes from Macau and other parts of China also arrived.

Timeline

- 1543 – Portuguese sailors arrive in Tanegashima and bring the arquebus.

- 1549 – Francis Xavier arrives in Kagoshima and introduces Christianity.

- 1557 – Macau is established by the Portuguese. Annual trading ships start going to Japan.

- 1571 – The Daimyō Ōmura Sumitada helps the Portuguese set up the port of Nagasaki.

- 1575 – Battle of Nagashino, where firearms are used a lot.

- 1580 – Ōmura Sumitada gives Nagasaki to the Society of Jesus forever.

- 1587 – Toyotomi Hideyoshi orders Portuguese missionaries to leave, but allows trade.

- 1592 – Japan invades Korea with a large army.

- 1597 – 26 Christians are crucified in Nagasaki.

- 1600 – William Adams arrives on the ship Liefde.

- 1603 – Edo becomes the seat of the Bakufu government.

- 1609 – The Dutch open a trading post in Hirado.

- 1613 – England opens a trading post in Hirado.

- 1614 – Jesuits are expelled from Japan. Christianity is forbidden.

- 1623 – The English close their trading post in Hirado because it's not profitable.

- 1624 – Japan stops diplomatic relations with Spain.

- 1634 – The artificial island Dejima is built to limit Portuguese merchants in Nagasaki.

- 1637 – Shimabara Rebellion by Christian peasants.

- 1639 – Trade with Portugal is permanently forbidden because of the Shimabara Rebellion.

- 1641 – The Dutch trading post is moved from Hirado to Dejima island.

See also

- History of the Catholic Church in Japan

- Nanban art

- Japanese–Portuguese conflicts

- Japan-Netherlands relations

- Japan-Spain relations

- Japan-Portugal relations

- Sengoku period

Images for kids

-

A Japanese lacquerware made for the Society of Jesus. 16th century.

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |