Hasekura Tsunenaga facts for kids

Hasekura Rokuemon Tsunenaga (支倉 六右衛門 常長 (1571–1622)) was a Japanese samurai and a loyal follower of Date Masamune. Date Masamune was a powerful daimyō (a feudal lord) who ruled the Sendai area in northern Japan. Hasekura came from a family with ancient ties to the Japanese emperors. In European records from his time, he was also known by names like Philip Francis Faxicura or Felipe Francisco Faxicura.

From 1613 to 1620, Hasekura led an important diplomatic trip called the Keichō Embassy. His main goal was to meet Pope Paul V in Rome. On his journey, he visited New Spain (which is now Mexico) and several places in Europe. On his way back, Hasekura and his group traveled through New Spain again in 1619. They sailed from Acapulco to Manila and then north to Japan, arriving in 1620. Many people consider him the first Japanese ambassador to visit the Americas and Spain.

Even though Hasekura's embassy was welcomed warmly in Spain and Rome, Japan was starting to crack down on Christianity at that time. European leaders also refused to agree to the trade deals Hasekura was hoping for. He returned to Japan in 1620 and sadly passed away from an illness a year later. His mission seemed to have few results, as Japan became more and more isolated from the rest of the world.

Japan would not send another embassy to Europe for more than 200 years. This was after two centuries of isolation, when the "First Japanese Embassy to Europe" finally took place in 1862.

Contents

Hasekura's Early Life

Hasekura Tsunenaga was born in 1571 in a place that is now part of Yonezawa in Yamagata Prefecture. His father, Yamaguchi Tsuneshige, also had family connections to Emperor Kanmu. Hasekura was a samurai of middle rank in the Sendai Domain. He served the powerful lord Date Masamune directly and received a good yearly payment. He spent his younger years at Kamitate Castle, which his grandfather had built. The name Hasekura comes from Hasekura Village, now a part of Kawasaki City.

Hasekura and Date Masamune were about the same age. Records show that Hasekura was often chosen for important missions as Masamune's representative. He also served as a samurai during the Japanese invasion of Korea in 1597.

In 1612, Hasekura's father was accused of corruption and was executed in 1613. His family's land was taken away. Normally, Hasekura would have been executed too. However, Date Masamune gave him a chance to regain his family's honor by putting him in charge of the important trip to Europe. Soon after, he also gave Hasekura back his family's lands.

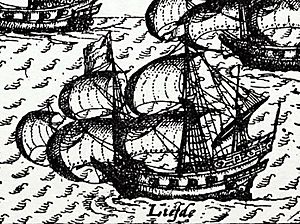

Japan's First Contacts with Spain

Spanish ships began sailing across the Pacific Ocean between New Spain (today's Mexico and California) and the Philippines in 1565. These famous ships, called Manila galleons, carried silver from Mexican mines to Manila. In Manila, the silver was used to buy spices and goods from all over Asia, including Japan. The return route for these ships took them northeast, following the Kuroshio Current (also known as the Japan Current) off the coast of Japan. From there, they sailed across the Pacific to the west coast of Mexico, landing in Acapulco.

Sometimes, Spanish ships were shipwrecked on the coasts of Japan due to bad weather. This led to some early meetings between the two countries. The Spanish wanted to spread the Christian faith in Japan. However, they faced strong opposition from the Jesuits, who had already started spreading Christianity in Japan in 1549. The Portuguese and Dutch also didn't want Spain to get involved in Japanese trade. Still, some Japanese, like Christopher and Cosmas, are known to have traveled across the Pacific on Spanish ships as early as 1587.

In 1609, a Spanish ship called the San Francisco was badly damaged in a storm near Japan. Its captain, Rodrigo de Vivero, was a former governor of the Philippines. He was granted a meeting with the retired shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu. De Vivero created a treaty that allowed Spaniards to build a trading post in eastern Japan. It also said that Spanish ships could visit Japan if needed, and that Japan would send an embassy to the Spanish court.

Early Japanese Trips to the Americas

A Franciscan friar named Luis Sotelo was teaching Christianity near what is now Tokyo. He convinced Tokugawa Ieyasu and his son Tokugawa Hidetada to send him to New Spain (Mexico) on a Japanese ship. This was to help with the trade treaty. In 1610, Rodrigo de Vivero, some Spanish sailors, Friar Sotelo, and 22 Japanese representatives sailed to Mexico. They traveled on the San Buenaventura, a ship built by the English sailor William Adams for the shōgun.

In New Spain, Friar Sotelo met with the Viceroy. The Viceroy agreed to send an ambassador to Japan. This ambassador was the famous explorer Sebastián Vizcaíno. Vizcaíno also had the job of looking for "Gold and Silver islands" that people thought were east of Japan.

Vizcaíno arrived in Japan in 1611. He had many meetings with the shōgun and other lords. However, his visit was difficult because he didn't respect Japanese customs. Also, the Japanese were becoming more resistant to Christianity, and the Dutch were working against Spanish plans. Vizcaíno eventually left to search for the "Silver island." He faced bad weather and had to return to Japan because his ship was badly damaged.

The San Sebastian in 1612

Before Vizcaíno returned, another ship was built in Japan. It was called the San Sebastian. This ship left for Mexico on September 9, 1612, with Luis Sotelo and two representatives from Date Masamune. Their goal was to move forward with the trade agreement with New Spain. However, the ship sank a few miles from Uraga, and the trip had to be called off.

The 1613 Embassy Plan

The shōgun decided to have a new large ship, called a galleon, built in Japan. This ship would take Vizcaíno back to New Spain. It would also carry a Japanese embassy, joined by Luis Sotelo. The galleon, named San Juan Bautista, was built in just 45 days. Many skilled workers helped, including 800 shipbuilders, 700 metalworkers, and 3,000 carpenters.

Date Masamune, the lord of Sendai, was put in charge of this project. He chose Hasekura to lead the mission. The ship left Ishinomaki-Tsukinoura on September 15, 1613. On board were Hasekura Rokuemon Tsunenaga and many other Japanese, including samurai, merchants, sailors, and servants. There were also about 40 Spaniards and Portuguese, including Sebastián Vizcaíno, who was just a passenger. In total, there were about 180 people.

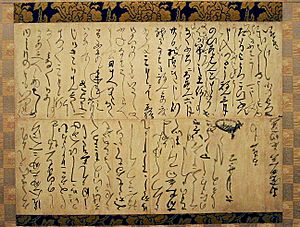

The Japanese embassy had two main goals: to discuss trade agreements with the Spanish king in Madrid and to meet with the Pope in Rome. Date Masamune was very keen to welcome the Catholic religion to his lands. He invited Sotelo and allowed Christianity to be taught there in 1611. In his letter to the Pope, which Hasekura carried, he wrote: "I'll offer my land for your missionary work. Send us as many priests as possible."

Sotelo later wrote about the journey, saying that the main reason for the mission was to spread Christianity in northern Japan. The embassy was likely also part of a plan to increase trade with other countries. However, this was before Christians took part in the Siege of Osaka. This event caused the shogunate to ban Christianity in the areas it controlled in 1614.

Journey Across the Pacific

After the ship was finished, it left on October 28, 1613, heading for Acapulco. There were about 180 people on board. This included 10 samurai from the shōgun's government, 12 samurai from Sendai, 120 Japanese merchants, sailors, and servants. There were also about 40 Spaniards and Portuguese, including Sebastián Vizcaíno, who was just a passenger.

Arrival in Acapulco, New Spain

The ship spotted Cape Mendocino on December 26, 1613. It then sailed along the California coast and landed at Zacatula on January 22, 1614. The group arrived in Acapulco on January 25, after three months at sea. The Japanese were welcomed with a grand ceremony. However, they had to wait in Acapulco for instructions on how to continue their journey.

There were some arguments between the Japanese and the Spaniards, especially Vizcaíno. These arguments seemed to be about how to handle gifts from the Japanese ruler. A journal from that time says that Vizcaíno was seriously hurt in one of these fights.

To bring peace, orders were given on March 4 and 5. These orders stated that "the Japanese should not be attacked in this Land." They were asked to give up their weapons until they left, except for Hasekura Tsunenaga and eight of his followers. The orders also said: "The Japanese will be free to go where they want, and should be treated properly. They should not be abused in words or actions. They will be free to sell their goods." These rules applied to everyone, and those who didn't follow them would be punished.

Mexico City, New Spain

The embassy stayed in Acapulco for two months. They then entered Mexico City on March 24, where they were again welcomed with a big ceremony. The main goal for the embassy was to travel on to Europe. The embassy spent some time in Mexico. Then, they went to Veracruz to board ships that would take them across the Atlantic.

A local historian named Chimalpahin wrote about Hasekura's visit:

"This is the second time that the Japanese have landed one of their ships on the shore at Acapulco. They are bringing iron goods, writing desks, and some cloth to sell here."

"It became known here in Mexico that their ruler, the Emperor of Japan, sent this lordly ambassador here to go to Rome. He was to see the Holy Father Paul V and show their respect to the holy church, because all the Japanese want to become Christians."

Hasekura stayed in a house next to the Convent of San Francisco. He met with the Viceroy. Hasekura explained that he also planned to meet King Philip III to offer peace and allow Japanese people to trade in Mexico. On April 9, 20 Japanese people were baptized, and 22 more on April 20. The archbishop in Mexico performed these baptisms at the Convent of San Francisco. In total, 63 of them received confirmation on April 25. Hasekura himself decided to wait until he reached Europe to be baptized.

Chimalpahin noted that Hasekura left some of his people behind before leaving for Europe:

"The Ambassador of Japan set out and left for Spain. He divided his followers; he took some Japanese, and he left an equal number here as merchants to trade and sell things."

The fleet left for Europe on the San Jose on June 10. Hasekura had to leave most of the Japanese group behind. They were to wait in Acapulco for the embassy to return.

Some of these Japanese, along with those from an earlier trip, returned to Japan that same year. They sailed back on the San Juan Bautista.

Stop in Cuba

The embassy stopped and changed ships in Havana, Cuba, in July 1614. They stayed in Havana for six days. A bronze statue of Hasekura was put up on April 26, 2001, at the entrance of Havana Bay.

Hasekura's Mission to Europe

Hasekura led the Keichō Embassy, a diplomatic mission to Pope Paul V and Europe from 1613 to 1620. This mission was important because it followed an earlier one, the Tenshō embassy of 1582. After crossing the Pacific on the San Juan Bautista, Hasekura traveled to New Spain (Mexico). He arrived in Acapulco and then left from Veracruz. He visited several other places in Europe on his journey. On the way back, Hasekura and his group returned through New Spain in 1619. They sailed from Acapulco to Manila and then north to Japan in 1620. He is often seen as the first Japanese ambassador to the Americas and Spain.

Spain

The fleet arrived safely in Sanlúcar de Barrameda, Spain, on October 5, 1614.

A local record states: "The Japanese ambassador Hasekura Rokuemon, sent by Joate Masamune, king of Boju, entered Seville on Wednesday, October 23, 1614. He was joined by 30 Japanese men with swords, their guard captain, and 12 archers and guards with painted spears and ceremonial blades. The guard captain was Christian and was called Don Thomas, the son of a Japanese martyr."

The Japanese embassy met with King Philip III in Madrid on January 30, 1615. Hasekura gave the King a letter from Date Masamune and offered a treaty. The King replied that he would do his best to help with these requests.

Hasekura was baptized on February 17 by the royal chaplain. He was renamed Felipe Francisco Hasekura in honor of the king and Sotelo's religious order. The Duke of Lerma, who was a very powerful official, became Hasekura's godfather.

The embassy traveled across Spain during the summer of 1615, with all expenses paid by the king. They finally received permission to travel to Rome in August and left at the beginning of that month.

France

After traveling through Spain, the embassy sailed across the Mediterranean Sea on three Spanish ships towards Italy. Due to bad weather, they had to stop for a few days in the French port of Saint-Tropez. There, they were welcomed by local nobles and caused quite a stir among the people.

The visit of the Japanese Embassy is written in the city's old records. It says the embassy was led by "Philip Francis Faxicura, Ambassador to the Pope, from Date Masamune, Lord of the Sendai Domain, Mutsu Province, Japan."

Many interesting details about their visit were written down:

- "They never touch food with their fingers. Instead, they use two small sticks that they hold with three fingers."

- "They blow their noses in soft silky papers the size of a hand. They never use a paper twice, so they throw them on the ground after use. They were amused to see our people around them rush to pick them up."

- "Their swords cut so well that they can cut a soft paper just by putting it on the edge and blowing on it."

Hasekura Tsunenaga's visit to Saint-Tropez in 1615 is the first recorded meeting between France and Japan.

Italy

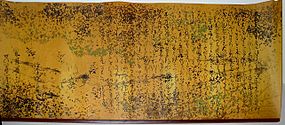

The Japanese Embassy arrived in Rome on September 20, 1615. They were welcomed by a Cardinal. The delegation met Pope Paul V on November 3. Hasekura gave the Pope two gold-decorated letters, one in Japanese and one in Latin. These letters asked for a trade agreement between Japan and Mexico and for Christian missionaries to be sent to Japan. These letters are still kept in the Vatican archives today.

The Latin letter, likely written by Luis Sotelo for Date Masamune, said in part:

"Kissing the Holy feet of the Great, Universal, Most Holy Lord of The Entire World, Pope Paul, in deep respect, I, Idate Masamune, King of Wōshū in the Empire of Japan, humbly say:

The Franciscan Padre Luis Sotelo came to our country to spread the faith of God. At that time, I learned about this faith and wanted to become a Christian. However, I haven't been able to do so yet because of some small problems. Still, to encourage my people to become Christians, I wish that you send missionaries from the Franciscan church. I promise that you will be able to build a church and that your missionaries will be safe. I also wish that you choose and send a bishop. Because of this, I have sent one of my samurai, Hasekura Rokuemon, as my representative to go with Luis Sotelo across the seas to Rome, to show you our obedience and to kiss your feet. Also, since our country and New Spain are close, could you help us talk with the King of Spain, so that missionaries can be sent across the seas?"

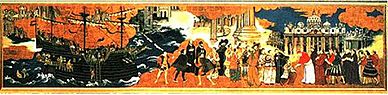

Bottom (left to right): (a) Hasekura talking with the Franciscan Luis Sotelo, surrounded by other embassy members, in a fresco showing the "glory of Pope Paul V". Sala Regia, Quirinal Palace, Rome, 1615.

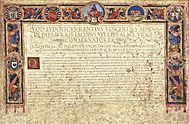

(b) Document granting Roman Noble and Roman Citizen titles to "Faxecura Rokuyemon".

The Pope agreed to send missionaries. However, he left the decision about trade to the King of Spain.

The Roman Senate also gave Hasekura the special titles of Roman Noble and Roman Citizen. He brought this document back to Japan, and it is still kept in Sendai today.

Second Visit to Spain

In April 1616, Hasekura met with the King of Spain again. This time, the King refused to sign a trade agreement. He said that the Japanese Embassy did not seem to be an official embassy from the true ruler of Japan, Tokugawa Ieyasu. In fact, Ieyasu had issued an order in January 1614 to expel all Christian missionaries from Japan and had begun persecuting Christians.

Two years later, after their trip around Europe, the mission left Seville for New Spain (Mexico) in June 1616. Some records suggest that some Japanese might have stayed in Spain. This is possible because they made their last stop in villages near Seville. Today, there are families in Spain with the surname "Japón," which means "Japan." These families are believed to be descendants of the members of Hasekura Tsunenaga's group.

Return to Mexico

Hasekura stayed in Mexico for five months on his way back to Japan. The San Juan Bautista had been waiting in Acapulco since 1616. It had made a second trip across the Pacific from Japan to Mexico. The ship, captained by Yokozawa Shōgen, was loaded with valuable pepper and lacquerware from Kyoto, which were sold in Mexico. To prevent too much silver from leaving Mexico for Japan, the Spanish king asked that the money from the sales be spent on Mexican goods. However, Hasekura and Yokozawa were allowed to take some silver back with them.

Philippines

In April 1618, the San Juan Bautista arrived in the Philippines from Mexico, with Hasekura and Luis Sotelo on board. The Spanish government there bought the ship. They wanted to use it to defend against attacks from Protestant countries. In Manila, the archbishop wrote to the king of Spain about the deal in a letter dated July 28, 1619.

During his time in the Philippines, Hasekura bought many goods for Date Masamune. He also built a ship, as he explained in a letter to his son. He finally returned to Japan in August 1620, arriving at the port of Nagasaki.

Return to Japan

By the time Hasekura came back, Japan had changed a lot. An effort to get rid of Christianity had been happening since 1614. Tokugawa Ieyasu had died in 1616 and was replaced by his son, Tokugawa Hidetada, who was more suspicious of foreigners. Japan was also moving towards a policy of "Sakoku" or isolation. Because news of these persecutions reached Europe during Hasekura's trip, European rulers, especially the King of Spain, became very unwilling to agree to Hasekura's trade and missionary requests.

Hasekura reported his travels to Date Masamune when he arrived in Sendai. Records show that he gave Masamune a portrait of Pope Paul V, a painting of himself praying, and a set of daggers from Sri Lanka and Malaysia/Indonesia that he bought in the Philippines. All these items are now kept in the Sendai City Museum. The "Records of the House of Masamune" describe his report briefly. They end with a surprising phrase, "奇怪最多シ" (meaning "most strange and extraordinary"), about Hasekura's stories.

Christianity Banned in Sendai

Just two days after Hasekura returned to Sendai, an order against Christians was announced in the Sendai area. This order had three main points:

- First, all Christians were told to give up their faith, following the shōgun's rules. If nobles refused, they would be sent away. If common people, farmers, or servants refused, they would be killed.

- Second, a reward would be given to anyone who reported hidden Christians.

- Third, those who spread the Christian faith had to leave the Sendai area or give up their religion.

We don't know exactly what Hasekura said or did to cause this. Later events suggest that he and his family remained faithful Christians. Hasekura might have given a very enthusiastic, and perhaps unsettling, account of the power of Western countries and the Christian religion. He might also have suggested an alliance between the Church and Date Masamune to take over Japan. This idea was promoted by the Franciscans in Rome, but it would have been totally unrealistic in Japan in 1620. Finally, hopes for trade with Spain disappeared when Hasekura reported that the Spanish King would not make a deal as long as Christians were being persecuted in Japan.

Date Masamune suddenly decided to distance himself from the Western faith. The first executions of Christians began 40 days later. However, the anti-Christian actions taken by Date Masamune were relatively mild compared to other areas. Japanese and Western Christians often said that he only took these actions to please the shōgun.

One month after Hasekura's return, Date Masamune wrote a letter to the shōgun Tokugawa Hidetada. In it, he tried very hard to avoid responsibility for the embassy. He explained in detail how it was organized with the shōgun's approval and even help.

Spain, with its colony and army in the nearby Philippines, was a concern for Japan at that time. Hasekura's firsthand stories about Spanish power and their colonial methods in New Spain (Mexico) might have made the shōgun Tokugawa Hidetada decide to cut off trade relations with Spain in 1623 and diplomatic relations in 1624. Other events, like Spanish priests secretly entering Japan and a failed Spanish embassy, also contributed to this decision.

Hasekura's Death

What happened to Hasekura after his return is not fully known. There are many stories about his last years. Christian writers at the time only had rumors. Some said he gave up Christianity, others that he was killed for his faith, and some that he practiced Christianity in secret. The fact that his children and servants were later executed for being Christians suggests that Hasekura remained a strong Christian and passed his faith on to his family.

Sotelo, who returned to Japan but was caught and burned at the stake in 1624, said before his execution that Hasekura returned to Japan as a hero who spread the Christian faith.

Hasekura also brought several Catholic items back to Japan. He did not give them to his lord but kept them on his own property.

Hasekura Tsunenaga died of an illness in 1622, according to both Japanese and Christian sources. The exact location of his grave is not known for sure. Three graves in Miyagi are claimed to be Hasekura's. The most likely one is in the town of Ōsato at the Saikō-ji temple. Another is at the Buddhist temple of Enfuku-ji in Kawasaki town. A third is clearly marked (along with a memorial to Sotelo) in the cemetery of the Kōmyō-ji temple in Sendai.

His Family's Fate

Hasekura had a son named Rokuemon Tsuneyori. In 1637, two of his son's servants were found to be Christian. They refused to give up their faith even under torture and died. In the same year, Rokuemon Tsuneyori himself was suspected of being Christian. However, he avoided being questioned because he was the head of a Zen temple.

In 1640, two more of Tsuneyori's servants were found to be Christian. One of them, Tarōzaemon, had traveled with Hasekura to Rome. They also refused to give up their faith under torture and died. This time, Tsuneyori was held responsible and executed on the same day, at age 42. He was punished for not reporting Christians living in his home, even though it was not confirmed if he was Christian himself. Two Christian priests had mentioned his name under torture. Tsuneyori's younger brother, Tsunemichi, was also found to be Christian but managed to escape and disappear.

The Hasekura family's special rights were taken away by the Sendai lord, and their property and belongings were seized. It was at this time, in 1640, that Hasekura's Christian items were taken. They were kept in Sendai until they were rediscovered in the late 1800s.

About fifty Christian items were found in Hasekura's estate in 1640. These included crosses, rosaries, religious robes, and religious paintings. These items were taken and stored by the Date family. An inventory was made again in 1840, describing the items as belonging to Hasekura Tsunenaga. Nineteen books were also mentioned, but they have since been lost. Today, the items are kept in the Sendai City Museum and other museums in Sendai.

Tsuneyori's son, Tsunenobu, who was Hasekura Tsunenaga's grandson, survived. He started a line of the Hasekura family that continues to this day. The first ten heads of the Hasekura Family lived in Osato City. The eleventh head moved to Sendai City, where the current 13th head, Tsunetaka Hasekura, lives.

Hasekura's Legacy

The story of Hasekura's travels was largely forgotten in Japan until the country reopened after its long period of isolation. In 1873, a Japanese embassy to Europe, led by Iwakura Tomomi, first learned about Hasekura's journey when they were shown documents during their visit to Venice, Italy.

Today, there are statues of Hasekura Tsunenaga in several places. You can find them near Acapulco in Mexico, at the entrance of Havana Bay in Cuba, in Coria del Río in Spain, in the Church of Civitavecchia in Italy, in Tsukinoura near Ishinomaki, and two in Osato town in Miyagi. About 700 people in Coria del Río have the last name Japón (meaning "Japan"). They are believed to be descendants of the members of Hasekura Tsunenaga's group. A theme park that tells the story of the embassy and has a replica of the San Juan Bautista was built in the harbor of Ishinomaki, where Hasekura first started his voyage.

Stories Based on His Life

Shūsaku Endō wrote a novel in 1980 called The Samurai. It's a fictional story about Hasekura's travels. In 2005, a Spanish animated film called Gisaku told the adventures of a young Japanese samurai named Yohei who visited Spain in the 17th century. This story was loosely inspired by Hasekura's journey. Yohei survives to the present day thanks to magic powers and becomes a superhero in modern Europe.

The 2017 historical novel The Samurai of Seville by John J. Healey tells the story of Hasekura and his group of 21 samurai. A sequel in 2019, The Samurai's Daughter, tells the story of a young woman born to one of the samurai and a Spanish lady, and her journey to Japan with her father.

The 2018 French movie Un samouraï au Vatican, directed by Stéphane Bégoin, is also based on the diplomatic mission to Europe led by Hasekura Tsunenaga.

See also

In Spanish: Hasekura Tsunenaga para niños

In Spanish: Hasekura Tsunenaga para niños

- Bernardo the Japanese, the first Japanese to visit Europe, in 1553.

- William Adams, the first Englishman who traveled to Japan.

- Edo period

- Nanban trade

- Tenshō embassy (天正遣欧少年使節) – an earlier embassy sent by Japanese lords to Europe in the 1580s.

- Itō Mancio – leader of the Tenshō embassy.

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |