Captaincy General of the Philippines facts for kids

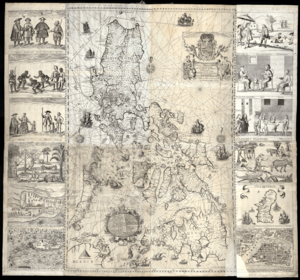

The Captaincy General of the Philippines (called Capitanía General de Filipinas in Spanish) was a special area of the Spanish Empire in Southeast Asia. It was ruled by a governor-general. For a long time, it was connected to the Viceroyalty of New Spain in Mexico City.

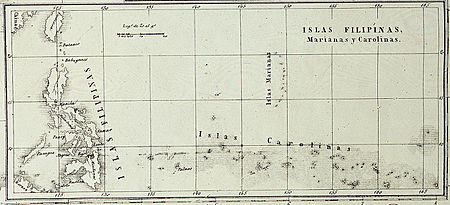

After Mexican independence in 1821, the Philippines was ruled directly from Madrid, Spain. This area included the Philippine Islands, the Mariana Islands, and the Caroline Islands. Spain set up its first lasting forts here in 1565. The Captaincy General ended in 1898 when the First Philippine Republic was formed after the Philippine Revolution.

Quick facts for kids

Captaincy General of the Philippines

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1565–1898 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Motto: Plus Ultra

"Further Beyond" |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Captaincy General | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Spanish (official) Tagalog (common) Philippine languages, Micronesian languages |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism (state religion), Islam, Philippine traditional religion | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1565–1598 (first)

|

Philip II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1886–1898 (last)

|

Alfonso XIII | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor-General | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1565–1572 (first)

|

Miguel López de Legazpi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1898 (last)

|

Diego de los Ríos | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Cortes Generales | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• European rule

|

27 April 1565 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15 March 1646 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24 September 1762 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 January 1872 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19 August 1896 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Declaration of Independence

|

12 June 1898 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 December 1898 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Spanish dollar, Spanish peseta | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC-16, -15, -14, -13, and -12 (1565-1844) +8, +9, +10, +11, and +12 (1845 onwards) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | PH | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Contents

History of Spanish Rule

Early Explorations

After a very long trip across the Pacific Ocean, Ferdinand Magellan reached the island of Guam on March 6, 1521. He then sailed to the Philippines. Magellan died during the Battle of Mactan. Antonio Pigafetta, who wrote down the details of the trip, was one of the few who survived Magellan's journey around the world.

In 1565, Miguel López de Legazpi arrived in Guam and claimed it for Spain. He then went to the Philippines. There, his group quickly took control of Cebu, Samar, Leyte, and Bohol. They later conquered Manila.

In 1569, Legazpi moved the Spanish base from Cebu to Panay. They found allies there. These allies were not conquered by force but became partners through agreements. From Panay, the Spanish planned to conquer Luzon. This plan started on May 8, 1570. Two of Legazpi's commanders, Martín de Goiti and Juan de Salcedo, conquered Luzon's northern areas.

Spain claimed several other Pacific islands in the 1500s. These included the Caroline Islands, Palau, and New Guinea. However, Spain did not try to build permanent towns on these islands until the 1700s.

Spanish Settlement and Government

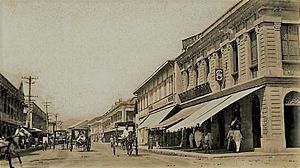

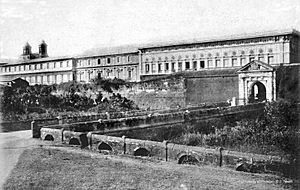

In 1574, the Captaincy General of the Philippines was officially created. It was part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. In 1584, King Felipe II set up the Real Audiencia of Manila, which was like a high court. The Captaincy General's capital was in Cebu from 1565 to 1595. After that, it moved to Manila and stayed there until 1898.

Over time, the way the government worked changed. After 1822, all Governor-Generals were military leaders. Many local government offices and military bases were set up in the 1800s. This was because there were many islands and large areas to control.

How the Philippines Was Governed

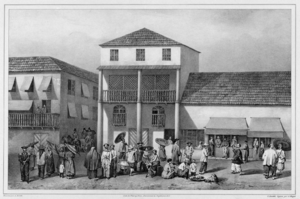

The Spanish quickly set up their government system in the new colony. One of the first things they did was to move native Filipinos into new settlements. These settlements were usually built around a central plaza.

Early Local System

The first system used was called the encomienda system. This was similar to the feudal system in old Europe. Spanish leaders, priests, and local nobles were given large areas of land. In return, they had to serve the King. They could also collect taxes from the people living on their land.

The person who received the encomienda was called an encomendero. They had to protect the people, provide justice, and govern the area. In times of war, they had to provide soldiers for the King. This was especially important to defend against attacks from the Dutch or British. However, encomenderos often abused their power. By 1700, this system was mostly replaced by provinces. Each province was led by an alcalde mayor, who was a provincial governor.

National Government

At the top level, the King of Spain ruled through his special council, the Council of the Indies. In the Philippines, the King's main representative was the Governor-General of the Philippines. The Governor-General's main office was in Intramuros, Manila.

The Governor-General had many important jobs:

- He was the head of the supreme court, called the Royal Audiencia of Manila.

- He was the commander of the army and navy.

- He planned the country's economy.

- He oversaw all local government decisions.

- He also supervised church activities and appointments.

The Governor-General was usually a peninsular Spaniard, meaning someone born in Spain. This was to make sure they were loyal to the Spanish King.

Provincial Government

At the local level, the peaceful provinces were led by a provincial governor, called an alcalde mayor. Military zones, like Mariveles, were led by corregidores. City governments were also led by an alcalde mayor.

These leaders had many powers. They acted as judges, police chiefs, and tax collectors. They also led the provincial military. They could even engage in trade, which sometimes led to unfair practices. Alcaldes mayores were often Insulares, Spaniards born in the Philippines. Later, Spaniards from Spain started taking these jobs, which caused some unrest.

Town Government

The pueblo, or town, was led by the Gobernadorcillo, meaning "little governor." His jobs included:

- Making lists for collecting taxes.

- Finding and organizing men for public work and military service.

- Working as a postal clerk.

- Acting as a judge for small legal problems.

His yearly salary was small, but he did not have to pay taxes. Any native Filipino or Chinese mestizo (mixed race) who was 25 years old and could speak Spanish could become a gobernadorcillo. They also had to have been a cabeza de barangay for four years.

These officials came from the Principalía, which was the noble class before the Spanish arrived. Many famous Filipino families today have names that come from these old noble families.

Village Government

Each barangay was divided into "barrios" (villages or districts). The barrio government was run by the barrio administrator, called a cabeza de barangay. He was in charge of keeping peace and order. He also found men for public works and collected taxes for the barrio. Cabezas had to be able to read and write Spanish. They also needed to have good character and own property. If a cabeza served for 25 years, they were excused from forced labor.

Checking Officials

To prevent royal officials from abusing their power, two old Spanish systems were used:

- The Residencia: This was a public review of an official's actions at the end of their term.

- The Visita: This was a secret inspection by a special visitor from Spain. It could happen at any time without warning.

Maura Law

The Maura Law was passed on May 19, 1893. It was named after Antonio Maura, the Spanish Minister of Colonies. This law reorganized town governments in the Philippines. The goal was to make them more effective and independent. This law created the local government structure that was later used and improved by American and Filipino governments.

Economy During Spanish Rule

The Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade

Manila was a very important trading center in Asia during the 1600s and 1700s. The Manila galleons were large ships built in places like Bicol and Cavite. These ships sailed between Manila and Acapulco, Mexico. From Mexico, goods were sent across the Atlantic Ocean to Spain.

Many products from China, Japan, and India came to Manila. They were sold for silver coins that arrived from Acapulco. These goods, like silk, porcelain, and spices, were then sent to Acapulco. From there, they went to other parts of New Spain, Peru, and Europe.

The Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade was the main way the colony earned money in its early years. It started in 1565 and lasted until the early 1800s. This trade brought silver from Mexico to buy Asian goods. It also brought new crops and animals to the Philippines, such as tomatoes, avocado, guava, and horses. This trade helped the colony earn its first real income. It stopped in 1815.

Royal Society of Friends of the Country

In 1780, the Spanish Royal Economic Society of Friends of the Country was created. This group was made up of smart people who wanted to come up with new, helpful ideas. They helped with farming and set up a design academy. They also helped create the first paper mill in the Philippines in 1825. This society existed on and off until the 1890s.

Royal Company of the Philippines

On March 10, 1785, King Charles III of Spain approved the Royal Philippine Company. This company had a special right to bring Chinese and Indian goods into the Philippines. It could also ship goods directly to Spain around the Cape of Good Hope. Other countries like the Dutch and British did not like this company because it competed with their trade. This company, along with the Galleon trade, eventually ended in the early 1800s.

Taxes and Forced Labor

People in the Philippines had to pay taxes. One tax was called bandalâ. This was a forced sale of goods like rice to the government each year. There were also customs duties and income taxes. By 1884, the main tax was replaced by the cedula personal. Everyone over 18 had to pay for this personal identification. Local gobernadorcillos were in charge of collecting these taxes. If someone could not show their cedula receipt, they could be arrested.

Besides paying taxes, all Filipino men and Chinese immigrants aged 16 to 60 had to do forced labor, called "polo." This labor lasted for 40 days a year, but later it was reduced to 15 days. They built and repaired roads and bridges, constructed public buildings and churches, cut timber, worked in shipyards, and served as soldiers. People who did this labor were called "polistas." They could be excused by paying a fee called "falla." By law, polistas were supposed to get a daily rice meal, but they often did not receive it.

Resistance Against Spanish Rule

Spanish rule in the Philippines was often challenged by local rebellions. There were also invasions from the Dutch, Chinese, Japanese, and British. Many local groups resisted Spanish rule because they did not want to pay taxes or accept Spanish control. However, most of these rebellions were put down by the Spanish and their Filipino allies by 1597. In some areas, the Spanish let local groups manage their own affairs, but still under Spanish control.

At first, the Philippines was governed from Mexico City. But after Mexico became independent in 1821, Spain ruled the Philippines directly from Madrid. This made it harder for Spain to send supplies and manage the Philippines.

Early Resistance

Resistance against Spain did not stop after the first conquests. Many Filipino nobles fought against Spanish rule. Throughout their time in power, the Spanish faced many revolts across the country. Most of these were stopped, but some ended with agreements between the Spanish and the rebel leaders.

The Spanish–Moro conflict lasted for hundreds of years. In the late 1800s, Spain took control of parts of Mindanao and Jolo. The Moro Muslims in the Sultanate of Sulu then officially accepted Spanish rule.

During the British occupation of Manila (1762–1764), Diego Silang was made governor of Ilocos by the British. After he was killed, his wife Gabriela continued to lead the fight against Spanish rule. Resistance was often based on different local groups. Spanish culture did not spread to the mountainous parts of northern Luzon or the inland areas of Mindanao.

Freemasonry and Revolution

Freemasonry became popular in Europe and the Americas in the 1800s. It also came to the Philippines. Many people in the Western world wanted less political control from the Catholic Church.

The first Filipino Masonic lodge was Revolución, started by Graciano López Jaena in Barcelona in 1889. Later, Marcelo H. del Pilar started the Solidaridad in Madrid. Famous Filipinos like José Rizal joined this group.

In 1891, a Masonic lodge called Nilad was set up in the Philippines. By 1893, there were many Masonic lodges across the islands. The first Filipino woman Freemason was Rosario Villaruel. Many other women also joined.

Freemasonry was important during the Philippine Revolution. It helped push for reforms and spread new ideas. Many people who wanted a full revolution, like Andrés Bonifacio, were Freemasons. The way Bonifacio organized the Katipunan (a revolutionary group) was based on Masonic structures. Joining Masonry was something that both reformers and revolutionaries shared, even if they had different ideas about how to achieve change.

Territorial Divisions

By the second half of the 1700s, the Philippines was divided into 24 provinces. These included 19 alcaldías mayores (major provinces) and five corregimientos (military districts).

Some of the main provinces were:

- Albay

- Camarines

- Tayabas

- Cagayán

- Ilocos

- Pangasinán

- Pampanga

- Bulacan

- Tondo

- Laguna

- Balayán

- Leyte

- Panay

- Cebú

- Marianas

Over time, new provinces were created by dividing existing ones. For example, Bataan was separated from Pampanga in 1754. Ilocos was divided into Ilocos Norte and Ilocos Sur in 1818.

By the late 1800s, the main administrative units included:

- Luzon Island (20 areas)

- Mindoro, Marinduque, Luban, Ilin (one area)

- Batán (one area)

- Panay Island (three areas)

- Negros (one area)

- Samar (one area)

- Leite (one area)

- Calamianes (one area)

- Cebú (one area)

- Mindanao (four areas)

- Sultanate of Sulu and Joló

- Marianas (with capital Agaña, Guam)

- Palau

- Bonin Islands (now part of Japan)

- Spratly Islands

- Caroline Islands

- Marshall Islands (later sold to Germany)

Spanish rule in the Philippines ended in 1898 after a war with the United States. The U.S. took control of most territories. The remaining Pacific islands were sold to Germany in 1899.

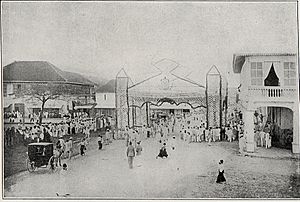

Images for kids

Gallery

See also

In Spanish: Capitanía General de Filipinas para niños

In Spanish: Capitanía General de Filipinas para niños

- History of the Philippines (1565–1898)

- Spanish East Indies

- Spanish Filipino

- New Spain

- Governor-General of the Philippines

- Royal Audience of Manila

- Spanish Empire

- Viceroyalty of New Spain

- History of the Philippines

Sources