Intramuros facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Intramuros

|

||

|---|---|---|

|

District

|

||

|

Clockwise, from top left: Intramuros entrance (Parian gate), Baluarte de San Diego, Fort Santiago, Ayuntamiento de Manila, Plaza San Luís Complex, San Agustin Church, Tranvía, Manila Cathedral.

|

||

|

||

| Nicknames:

Old Manila; the Walled City

|

||

| Motto(s):

Insigne y siempre leal

Distinguished and ever loyal |

||

| Country | Philippines | |

| Region | National Capital Region | |

| City | Manila | |

| Congressional District | 5th District of Manila | |

| Barangays | 5 | |

| Settled | June 12, 1571 | |

| Founded by | Miguel López de Legazpi | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 0.67 km2 (0.26 sq mi) | |

| Population

(2024 census)

|

||

| • Total | 7,437 | |

| • Density | 11,100/km2 (28,750/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | UTC+08:00 (Philippine Standard Time) | |

| Zip codes |

1002

|

|

| Area codes | 2 | |

Intramuros means "within the walls" or "inside the walls." It is a historic walled area in Manila, the capital of the Philippines. This special district covers about 0.67 square kilometers (0.26 square miles). The Intramuros Administration manages it with help from the city government.

Intramuros is a very old district completely surrounded by strong walls. During the time of the Spanish Empire, it was considered the entire City of Manila. Other towns outside the walls were called extramuros, meaning "outside the walls." These towns became part of Manila much later.

Intramuros was once the main government center for the Spanish colony in the Philippines. The governor-general lived there from 1571 until 1865. It was also a major hub for religion, education, and trade. Goods were shipped to and from Acapulco, Mexico, through the Manila galleon trade.

In the early 1900s, under American rule, the coastline changed. The walls and fort became hidden from the bay. The moat around the walls was drained and turned into a golf course. Sadly, during the Battle of Manila in 1945, World War II completely destroyed Intramuros. Even though rebuilding started right after the war, many original buildings are still gone. Today, the Intramuros Administration is working to restore its cultural heritage.

While Intramuros is no longer the main seat of the Philippine government, some government offices are still there. It also remains an important education center, home to several universities. Many offices of the Philippine Catholic Church are also in the district.

Intramuros was named a National Historical Landmark in 1951. Its fortifications are considered National Cultural Treasures because of their history and culture. San Agustín Church, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is located inside the walled district. Intramuros is even being considered for future UNESCO World Heritage Site status as "The Walled City and Historic Monuments of Manila."

Contents

Exploring Intramuros' Past

Early Beginnings: Before the Spanish Arrived

Manila's location was perfect for trade. It was on Manila Bay and at the mouth of the Pasig River. This made it a great spot for Tagalog tribes to trade with merchants from places like China and India. The old settlement of Maynila was exactly where Intramuros stands today.

In 1564, Spanish explorers led by Miguel López de Legazpi sailed from Mexico. They reached Cebu in 1565, setting up the first Spanish settlement in the Philippines. Legazpi heard about the rich resources in Maynila. He sent his commanders, Martín de Goiti and Juan de Salcedo, to explore Luzon island.

The Spanish arrived in Luzon in 1570. After some conflicts, the Spanish defeated the local Muslim leaders. They then made a peace agreement with Rajah Sulaiman III, Lakan Dula, and Rajah Matanda. These leaders handed over the city to the Spanish.

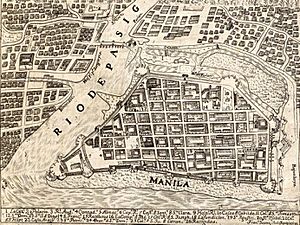

Spanish Rule: Building the Walled City (1571–1898)

Legazpi made Manila the new capital of the Spanish colony on June 24, 1571. He chose it for its great location and resources. He also declared that the Monarchy of Spain now ruled the entire group of islands. King Philip II of Spain was very happy with Legazpi's success. He gave the city a special coat of arms and called it: Ciudad Insigne y Siempre Leal (meaning "Distinguished and Ever Loyal City"). Intramuros became the main political, military, and religious center for Spain in Asia.

The city faced constant dangers from natural disasters and attacks. In 1574, Chinese pirates led by Limahong attacked and destroyed the city. The Spanish eventually drove them away, and the survivors had to rebuild. These attacks showed the need for strong walls.

Building the stone city began under Governor-General Santiago de Vera. A Jesuit priest, Antonio Sedeno, planned the city. King Philip II approved the plans. The next governor-general, Gómez Pérez Dasmariñas, brought royal orders to build stone walls and a fort. Leonardo Iturriano, a Spanish military engineer, led the project. Chinese and Filipino workers built the walls.

Fort Santiago was rebuilt. A round fort, Nuestra Senora de Guia, was built to protect the city from the southwest. Money for construction came from taxes and fines. Work on the walls started in 1590 and continued until 1872. By 1592, the walls and forts were developing well. Because construction happened over many years, the walls didn't follow one single plan.

Improvements continued with later governor-generals. The Baluarte de San Diego was finished in 1644. This bastion, shaped like an "ace of spades," was the first large addition to the walls. Ravelins and reductos (outer defenses) were added to strengthen weak spots. A moat was built around the city, with the Pasig River as a natural barrier on one side. By the 1700s, the city was fully enclosed. The last parts of the walls were finished in the early 1800s.

Life Inside Colonial Intramuros

The main square of Manila was Plaza Mayor, now called Plaza de Roma. It was in front of the Manila Cathedral. To the east was the Ayuntamiento (City Hall). Across from it was the Palacio del Gobernador, where the Spanish governor-general lived. An earthquake in 1863 destroyed these three buildings and much of the city. The governor-general's home moved to Malacañang Palace. The City Hall and Cathedral were rebuilt, but not the Governor's Palace.

Inside the walls were many Roman Catholic churches. The oldest is San Agustin Church, built in 1607. Other churches were built by different religious orders. These included San Nicolas de Tolentino, San Francisco, Third Venerable Order, Santo Domingo, Lourdes, and San Ignacio churches. This made the small walled city known as the City of Churches.

Intramuros was also a major center for education. Convents and schools were set up by religious orders. The Dominicans founded the Universidad de Santo Tomás in 1611 and the Colegio de San Juan de Letrán in 1620. The Jesuits started the Universidad de San Ignacio in 1590, which was the first university in the Philippines. It closed in 1768 when the Jesuits were expelled. When the Jesuits returned, they founded the Ateneo Municipal de Manila in 1859.

In the early days of Spanish rule, about 1,200 Spanish families lived near Intramuros. About 600 lived inside the walls, and 600 lived in the suburbs. There were also about 400 Spanish soldiers stationed in the walled city.

American Period: Changes and War (1898–1946)

After the Spanish–American War, Spain gave the Philippines to the United States in 1898. The American flag was raised at Fort Santiago, marking the start of American rule. The Ayuntamiento became the seat of the Philippine Commission in 1901. Fort Santiago became the headquarters for the United States Army.

The Americans made big changes to Manila. In 1903, parts of the walls were removed to improve the wharves along the Pasig River. The stones were used for other construction projects.

The walls were also opened in four places to make it easier to enter the city. The two moats around Intramuros were filled in with mud from Manila Bay. These moats were then turned into a municipal golf course.

New land was created for the Port of Manila, the Manila Hotel, and Rizal Park. This hid the old walls and city skyline from Manila Bay. The Americans also opened the first public high school, Manila High School, in 1906 on Victoria Street. In 1936, a law was passed requiring all new buildings in Intramuros to look like Spanish colonial architecture.

World War II and Japanese Occupation

In December 1941, the Imperial Japanese Army invaded the Philippines. The Santo Domingo Church and the original University of Santo Tomas campus in Intramuros were destroyed. General Douglas MacArthur declared Manila an "open city" because it could not be defended.

In January 1945, American troops returned to free Manila. Fierce fighting happened between American and Filipino soldiers against 30,000 Japanese defenders. Both sides caused huge damage to the city. Japanese troops also carried out the Manila massacre.

The Japanese army was pushed back into Intramuros. General MacArthur approved heavy bombing of the walled city. This bombing killed over 16,665 Japanese soldiers inside Intramuros. Two of the eight gates were badly damaged by American tanks. The bombings destroyed most of Intramuros, leaving only 5% of its buildings standing. About 40% of the walls were also destroyed. Over 100,000 Filipinos died during the Battle of Manila from February 3 to March 3, 1945.

By the end of World War II, almost all buildings in Intramuros were destroyed. Only the damaged San Agustin Church remained standing.

Modern Times: Rebuilding and Revival (1946–Present)

In 1951, Intramuros was declared a historical monument. Fort Santiago became a national shrine. The goal was to restore and rebuild Intramuros. However, a later law in 1956 allowed new development that didn't always respect the area's history. Many laws followed, but progress was slow due to limited money.

In 1979, the Intramuros Administration (IA) was created. Its job is to restore, manage, and develop the historic walled area. Since then, the IA has been slowly restoring the walls, forts, and buildings. The five remaining original gates have been restored or rebuilt. These include Isabel II Gate, Parian Gate, Real Gate, Santa Lucía Gate, and Postigo Gate. Walkways now connect the areas where the Americans breached the walls.

Buildings destroyed during the war have been rebuilt. The Manila Cathedral reopened in 1958. The Ayuntamiento de Manila was rebuilt in 2013. The San Ignacio Church and Convent is currently being rebuilt as the Museo de Intramuros, a museum.

In January 2015, Pope Francis visited the Philippines. He led a mass at the Manila Cathedral. In 2016, Anthology, an architecture and design festival, started using Fort Santiago as a venue. The Department of Tourism and the Intramuros Administration also launched a project for the 2018 Lenten season. For the first time since World War II, people could visit seven religious sites in Intramuros for Visita Iglesia. These included the Manila Cathedral and San Agustin Church.

In March 2018, the iMake History Fortress opened at the Baluarte de Santa Barbara in Fort Santiago. It's the world's first history-based Lego education center. In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic caused the Intramuros Administration to temporarily close sites like Fort Santiago and Museo de Intramuros.

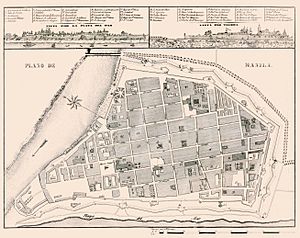

The Mighty City Walls

The stone walls of Intramuros have an uneven shape. They follow the curves of Manila Bay and the Pasig River. The walls covered an area of about 64 hectares (158 acres). They were made of stones about 8 feet (2.4 meters) thick and rose up to 22 feet (6.7 meters) high. The walls stretched for about 3 to 5 kilometers (1.9 to 3.1 miles). An inner moat surrounded the wall, and an outer moat faced the city.

Defense Structures: Protecting the City

Many bulwarks (baluarte), ravelins (ravellin), and redoubts (reductos) were placed along the walls. These followed medieval fort designs. There are seven main bastions, including Tenerias, Aduana, San Gabriel, San Lorenzo, San Andres, San Diego, and Plano. They were built at different times, so they look a bit different. The oldest is the Bastion de San Diego, built in 1587.

The fortifications had different parts. The side facing the sea and river was simpler. The three-sided land front had more bastions. Fort Santiago was built at the northwest tip where the sea and river meet. It served as a citadel (a strong fortress). Fort Santiago was a military headquarters for Spanish, British, American, and Japanese forces throughout history.

Inside Fort Santiago, there are bastions at each corner. The Baluarte de Santa Bárbara faces the bay and Pasig River. The Baluarte de San Miguel faces the bay. The Medio Baluarte de San Francisco faces the Pasig River.

City Gates: Entrances to the Past

Before the American Era, there were eight gates or Puertas to enter the city. These included Puerta Almacenes, Puerta de la Aduana, Puerta de Santo Domingo, Puerta Isabel II, Puerta del Parian, Puerta Real, Puerta Sta. Lucia, and Puerta del Postigo. Three of these gates were destroyed. The Almacenes Gate and the Santo Domingo/Customs Gate were removed by American engineers to make way for wharves.

The Banderas Gate was destroyed by an earthquake and never rebuilt. In the past, drawbridges were raised, and the city was closed from 11:00 pm to 4:00 am. Sentinels guarded the gates. This continued until 1852, when an earthquake led to a rule that the gates should stay open day and night.

Intramuros Today

Intramuros is the only district in Manila where you can still see many old Spanish-era influences. Fort Santiago is now a beautiful park and a popular place for tourists. Next to Fort Santiago is the rebuilt Maestranza Wall. This wall was removed by the Americans in 1903 to make the wharves wider. One day, the Intramuros Administration hopes to complete all the perimeter walls. This would allow people to walk all the way around the city on top of the walls.

There isn't much commercial development inside the district. A few fast-food places opened in the early 2000s, mainly for the students. Shipping companies also have offices there. Concerts, tours, and exhibitions are often held in Intramuros to attract visitors.

Building Styles: The Intramuros Register of Styles

The Intramuros Register of Styles is like a rulebook for how buildings should look in Intramuros. It's part of a national law, Presidential Decree No. 1616. The Intramuros Administration makes sure these rules are followed.

Intramuros is unique in the Philippines. For cultural reasons, the size, height, and look of all new buildings are strictly controlled by law. The Register of Styles guides how to build in the old Spanish colonial style.

This document is the first to describe the historical building styles of Intramuros in detail. It was written by Rancho Arcilla. It is the only architectural stylebook in the Philippines that is also a national law.

Most buildings in Intramuros used to be rowhouses without much space between them. Courtyards and backyards were common because they were good for the climate. The style was a mix of local and European. Churches and government buildings looked European but were adapted for the Philippines. Most other buildings, like the Bahay na bato, used local tropical designs. The Register of Styles usually requires new buildings to follow the Bahay na bato style. If a non-Bahay na Bato building (like a Neoclassical one) was known to exist in a specific spot, then a new building there can follow that older style.

Education: A Hub for Learning

Intramuros has been a center for education since colonial times. It was home to some of the oldest universities in the Philippines. These included the University of Santo Tomas (founded 1611), Colegio de San Juan de Letran (1620), and Ateneo de Manila University (1859). The University of Santo Tomas moved to a new campus in 1927. Ateneo moved out of Intramuros in 1952.

After World War II, new schools were built on the ruins. The Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila, founded in 1965, was built where the old Spanish Barracks stood. The Lyceum of the Philippines University, founded in 1952, was built on the site of the old San Juan de Dios Hospital.

The Mapúa University, founded in 1925, moved to Intramuros after the war. Its campus was built where the San Francisco Church and the Third Venerable Order Church once stood. These three new schools, along with Colegio de San Juan de Letran, formed a group called the Intramuros Consortium.

Churches: Places of Worship and History

Intramuros was a center of religious power during the Spanish colonial period. It had eight grand churches built by different religious orders. All but one of these churches were destroyed in the Battle of Manila. Only San Agustin Church, completed in 1607, survived the war. The Manila Cathedral, the main church for the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Manila, was rebuilt in 1958.

Other religious orders rebuilt their churches outside Intramuros after the war. The Dominicans rebuilt Santo Domingo Church in Quezon City. The Augustinian Recollects moved to their other church, the San Sebastian Church. The Capuchins moved the Lourdes Church to Quezon City in 1951. The San Ignacio Church and Convent is now being rebuilt as Museo de Intramuros, a museum about church history.

Monuments and Statues: Remembering the Past

Many historical monuments and statues were destroyed during World War II and other disasters. However, some have survived, and new ones have been added. You can still visit these important statues in Intramuros today.

| Name | Image | Location | Designers | Year | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolfo López Mateos Statue | Plaza Mexico 14°35′39″N 120°58′28″E / 14.59417°N 120.97444°E |

Luis A. Sanguino- Sculptor | This is a statue of Adolfo López Mateos, who was the President of Mexico from 1958 to 1964. | ||

| Anda Monument | Anda Circle | 1871 | It was first located near Fort Santiago. In 1957, it moved to Bonifacio Drive, where it stands today. | ||

| Benavides Monument | Plaza Santo Tomas | Tony Noël | 1889 | This is a copy. The original statue moved to the Sampaloc Campus in 1946. Its original base was destroyed in the Battle of Manila. | |

| Carlos IV monument | Plaza de Roma 14°35′32″N 120°58′23″E / 14.59222°N 120.97306°E |

A monument to Charles IV. | |||

| King Philip II Statue | Plaza de España 14°35′36″N 120°58′28″E / 14.59333°N 120.97444°E |

A monument to Philip II, after whom the Philippines is named. | |||

| Legazpi-Urdaneta Monument | Bonifacio Drive opposite the Manila Hotel | Agustí Querol Subirats | 1929 | Some of its metal decorations were stolen in 2012. | |

| Memorare – Manila 1945 Memorial (Shrine of Freedom) | Plazuela de Santa Isabel | 1995 | The words on the memorial were written by National Artist for Literature Nick Joaquin. | ||

| Queen Isabel II Statue | Puerta Isabel II | Ponciano Ponzano | 1860 | It was first located in front of Malate Church. The statue moved to the front of Puerta Isabel II in 1975. | |

| Rizal Statue | Rizal Shrine | This depicts Jose Rizal, the National Hero of the Philippines. | |||

| Rizal sa loob ng piitan | Rizal Shrine | This depicts Jose Rizal inside his prison cell. |

How Intramuros is Managed

The Intramuros Administration

The Intramuros Administration (IA) is part of the Department of Tourism. Its job is to carefully restore, manage, and develop the historic walled area of Intramuros. It also makes sure that buildings follow the 16th to 19th-century Philippine-Spanish architectural style. The IA handles daily tasks like giving out building permits and managing traffic. Its office is in the Palacio del Gobernador in Plaza Roma.

Barangays: Local Communities

Intramuros has five local communities called barangays, numbered 654 to 658. These barangays help with the well-being of the people living there. They do not have their own executive or legislative powers.

Barangays 654, 655, and 656 are in Zone 69 of Manila. Barangays 657 and 658 are in Zone 70.

| Barangay | Land area (km2) | Population (2024 census) |

|---|---|---|

| Zone 69 | ||

| Barangay 654 | 0.08678 | 1,492 |

| Barangay 655 | 0.2001 | 1,714 |

| Barangay 656 | 0.3210 | 519 |

| Zone 70 | ||

| Barangay 657 | 0.3264 | 919 |

| Barangay 658 | 0.2482 | 2,793 |

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Intramuros para niños

In Spanish: Intramuros para niños

- Spanish colonial fortifications in the Philippines

- Intramuros Consortium

- History of Manila