José Rizal facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

José Rizal

|

|

|---|---|

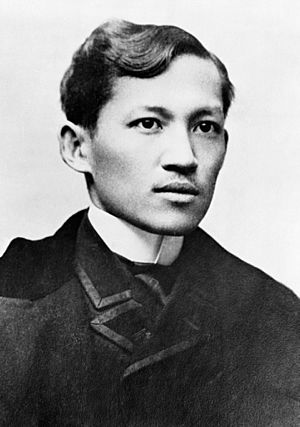

Rizal c. 1890s

|

|

| Born |

José Protasio Rizal Mercado y Alonso Realonda

June 19, 1861 |

| Died | December 30, 1896 (aged 35) Bagumbayan, Manila, Captaincy General of the Philippines, Spanish Empire

|

| Cause of death | Execution by firing squad |

| Resting place | Rizal Monument, Manila |

| Monuments |

|

| Other names | Pepe, Jose (nicknames) |

| Alma mater | |

| Organization | La Solidaridad, La Liga Filipina |

|

Notable work

|

|

| Movement | Propaganda Movement |

| Spouse(s) |

Josephine Bracken

(m. 1896) |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

José Rizal (born June 19, 1861 – died December 30, 1896) was a Filipino hero, writer, and a very talented person. He lived during the end of the Spanish rule in the Philippines. Many people consider him the national hero of the Philippines.

Rizal was an eye doctor. He also became a writer and an important member of the Propaganda Movement. This group wanted peaceful changes for the Philippines under Spain.

The Spanish government executed him because they thought he was involved in a rebellion. This rebellion was inspired by his writings. Even though he wasn't directly involved in planning the revolution, he agreed with its goals. These goals eventually led to Philippine independence.

Rizal is seen as one of the greatest heroes of the Philippines. He wrote two famous novels, Noli Me Tángere (1887) and El filibusterismo (1891). These books are like a national story for the Philippines. He also wrote many poems and essays.

Contents

Early Life and Family

José Rizal was born on June 19, 1861. His parents were Francisco Rizal Mercado y Alejandro and Teodora Alonso Realonda y Quintos. They lived in the town of Calamba in Laguna province. José had nine sisters and one brother.

His family rented land from the Dominicans, a religious group. In 1849, his parents' families added the surnames Rizal and Realonda. This was because the Spanish government wanted Filipinos to have Spanish surnames for counting people.

Like many families in the Philippines, the Rizals had mixed backgrounds. José's father's family came from China. His ancestor, Lam-Co, was a Chinese merchant who moved to the Philippines in the late 1600s. He changed his name to Domingo Mercado and became Catholic to avoid anti-Chinese feelings.

On his mother's side, Rizal had Chinese and Tagalog ancestors. He also had some Spanish ancestry. From a young age, José was very smart. He learned the alphabet from his mother at age 3. He could read and write by age 5.

When he started studying at the Ateneo Municipal de Manila, he used only "José Protasio Rizal." His brother, Paciano, advised him to drop the other names. This was so José could travel freely. It also helped him avoid being linked to his brother, who was known for his connections to Filipino priests who were executed.

José, using the name "Rizal," quickly became known for his poetry. His teachers were impressed by how well he spoke Spanish and other languages. He also wrote essays that criticized the Spanish history of the Philippines before their arrival. By 1891, when he finished his second novel, his last name "Rizal" was very famous. He wrote to a friend, "All my family now carry the name Rizal instead of Mercado because the name Rizal means persecution! Good! I too want to join them and be worthy of this family name..."

Education and Skills

Rizal first studied in Biñan, Laguna, before moving to Manila. He passed the entrance exam for Colegio de San Juan de Letran. But he chose to enroll at the Ateneo Municipal de Manila. He was one of nine students in his class to graduate with "outstanding" honors.

He continued his studies at Ateneo to become a land surveyor. At the same time, he studied law at the University of Santo Tomas. He earned excellent grades in his philosophy course.

When he learned his mother was going blind, he decided to study medicine. He specialized in eye care (ophthalmology). He trained at a hospital in Intramuros. In his last year of medical school, he received excellent marks in his medical courses.

Without his parents knowing, but with his brother Paciano's help, he traveled to Madrid in May 1882. He studied medicine at the Universidad Central de Madrid. He also attended medical classes in Paris and Heidelberg. In Berlin, he became a member of important scientific societies. He even gave a speech in German about the Tagalog language. He wrote a poem called "A las flores del Heidelberg" (To the Flowers of Heidelberg). It was a prayer for his homeland and for understanding between East and West.

In Heidelberg, Rizal finished his eye specialization in 1887. He worked under a famous professor, Otto Becker. He used the newly invented ophthalmoscope to examine his mother's eye. He wrote the last chapters of his first novel, Noli Me Tángere, there. It was published in Spanish later that year.

Rizal was a polymath, meaning he was skilled in many different areas. He painted, sketched, and made sculptures. He was a great poet, essayist, and novelist. His most famous novels, Noli Me Tángere (1887) and El filibusterismo (1891), talked about life during Spanish rule. These books inspired people who wanted peaceful changes and those who wanted a revolution.

Rizal was also a polyglot, meaning he could speak many languages. He knew twenty-two languages! His German friend, Dr. Adolf Bernhard Meyer, called his skills "stupendous." Rizal was an eye doctor, sculptor, painter, teacher, farmer, historian, writer, and journalist. He also knew about architecture, maps, economics, theater, martial arts, fencing, and pistol shooting. He joined the Freemasons in Spain.

Personal Life and Relationships

We know a lot about José Rizal's life because he wrote many diaries and letters. These writings have survived. His biographers found it challenging to translate his writings because he often switched between languages.

His diaries tell us about his travels. He wrote about his first time seeing the West. He also wrote about his trips back home, and his time in Hong Kong.

When Rizal was 16, he met Segunda Katigbak, a 14-year-old girl. He called her his first love in his memoir. However, Segunda was already engaged to someone else.

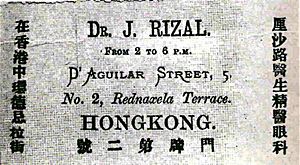

From December 1891 to June 1892, Rizal lived with his family in Hong Kong. He also had an eye clinic there. During his life, he was linked to several women. Two important relationships were with Leonor Rivera and Josephine Bracken.

Leonor Rivera

Leonor Rivera is believed to be the inspiration for the character of María Clara in Rizal's novels. They first met when Leonor was 14 and Rizal was 16. Their letters helped Rizal focus on his studies in Europe. They used codes in their letters because Leonor's mother did not like Rizal.

When Rizal returned to the Philippines in 1887, Leonor and her family had moved. Rizal's father told him not to see Leonor. This was to keep her family safe, as Rizal was already seen as a rebel because of his novel Noli Me Tángere. Rizal wanted to marry Leonor, but he never saw her again.

In 1888, Rizal stopped receiving letters from Leonor. Her mother wanted her to marry an Englishman named Henry Kipping. The news of Leonor's marriage made Rizal very sad.

Josephine Bracken

In February 1895, Rizal, then 33, met Josephine Bracken. She was an Irish woman from Hong Kong. She came with her blind adoptive father to have his eyes checked by Rizal. Rizal and Josephine fell in love. They wanted to marry, but the local priest would only allow it if Rizal got permission from the Bishop of Cebu. Rizal refused to change his beliefs, so the bishop did not give permission.

Josephine met Rizal's family in Manila. His mother suggested a civil marriage, which was a simpler ceremony. Rizal and Josephine lived together in Dapitan. They had a son, but he only lived for a few hours. Rizal named him Francisco, after his father.

Life in Europe and Writings

In 1890, Rizal moved to Brussels, Belgium. He was preparing to publish his notes on Antonio de Morga's book, Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas. He later moved to Madrid, Spain.

Rizal's most famous novels, Noli Me Tángere (published in Berlin in 1887) and El Filibusterismo (published in Ghent in 1891), made many people angry. These books criticized the Spanish friars and the power of the Church. Rizal's friend, Ferdinand Blumentritt, said that the characters in the novels were like real people. He said that the events in the books could happen any day in the Philippines.

Blumentritt warned that these books would cause Rizal to be seen as someone who started a revolution. Rizal was later tried by the military and executed. His books were thought to have helped start the Philippine Revolution of 1896.

Rizal was a leader of Filipino students in Spain. He wrote essays, poems, and articles for the Spanish newspaper La Solidaridad. He used pen names like "Dimasalang" and "Laong Laan." His writings focused on ideas of individual rights and freedom for Filipinos. He believed that the people of the Philippines were fighting against "a double-faced Goliath"—corrupt priests and bad government.

His writings asked for several changes:

- The Philippines to be a province of Spain.

- Filipinos to have representatives in the Spanish parliament.

- Filipino priests instead of Spanish friars in churches.

- Freedom to gather and speak.

- Equal rights for Filipinos and Spaniards under the law.

The Spanish rulers in the Philippines did not like these ideas.

Return to the Philippines and Exile

When Rizal returned to Manila in 1892, he started a group called La Liga Filipina. This group wanted peaceful social changes. But the governor quickly broke up the group. Rizal was already seen as an enemy by the Spanish because of his novels.

In July 1892, Rizal was sent away to Dapitan in Zamboanga. He lived there for four years. In Dapitan, he built a school, a hospital, and a water system. He also taught students and worked on farming.

His school taught in Spanish and included English. Rizal wanted to teach young men to be resourceful and self-sufficient. Many of his students later became successful farmers or honest government officials.

Rizal's best friend, Professor Ferdinand Blumentritt, kept in touch with him. They exchanged many letters in different languages. These letters confused the censors and delayed their delivery. Rizal's time in exile happened while the Philippine Revolution was starting. This made the Spanish court suspect he was involved.

Rizal did not support the uprising at first. He believed that peaceful change was better to avoid suffering. He said, "I consider myself happy for being able to suffer a little for a cause which I believe to be sacred [...]. I believe further that in any undertaking, the more one suffers for it, the surer its success."

Arrest and Execution

By 1896, the Philippine Revolution had become a full-blown uprising. Rizal had offered to work as a doctor in Cuba to help yellow fever victims. He was given permission to leave by Governor-General Ramón Blanco. Rizal and Josephine left Dapitan on August 1, 1896.

However, Rizal was arrested on his way to Cuba. He was imprisoned in Barcelona on October 6, 1896. He was sent back to Manila the same day to face trial. He was accused of being involved in the revolution. During his journey, he was not chained and had chances to escape, but he refused.

While in Fort Santiago, he wrote a statement. He said that Filipinos needed education and a strong national identity before they could be truly free. He did not support the current revolution.

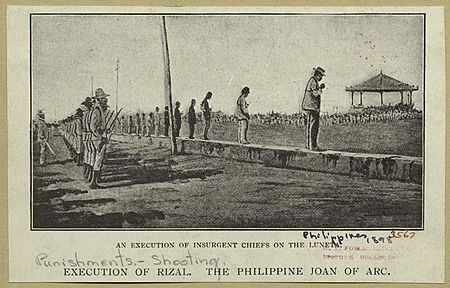

Rizal was tried by a military court. He was found guilty of rebellion, sedition, and conspiracy. He was sentenced to death. Governor Blanco, who was sympathetic to Rizal, was removed from office. A new governor, Camilo de Polavieja, took his place, which sealed Rizal's fate.

José Rizal was executed on December 30, 1896. He was shot by a squad of Filipino soldiers from the Spanish Army. Spanish troops stood ready to shoot the executioners if they didn't obey orders. A doctor checked Rizal's pulse just before he died, and it was normal. His last words were "consummatum est" – "it is finished."

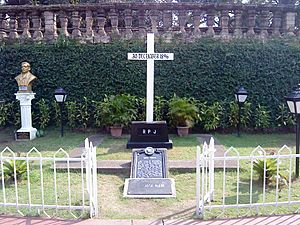

After the execution, Rizal was secretly buried in Pacò Cemetery (now Paco Park). His grave had no identification to prevent people from making him a martyr.

His poem Mi último adiós (My Last Farewell) was written a few days before his execution. It was later given to his family with his other belongings.

Exhumation and Re-burial

Rizal's sister, Narcisa, searched for his grave. She found guards at Paco Cemetery and saw a freshly dug grave. She believed it was her brother's. She asked the caretaker to place a marble slab with "RPJ" (Rizal's initials in reverse) on the grave.

In August 1898, after the Americans took Manila, Narcisa got permission to get Rizal’s remains. They found that Rizal was not buried in a coffin. He was wrapped in cloth and placed in the grave. His body was identified by his black suit and shoes.

His remains were taken to the Rizal family home. They were cleaned and placed in an ivory urn. The urn was later displayed to the public. On December 30, 1912, the urn was moved in a procession to its final resting place in Bagumbayan (now Rizal Park). The Rizal Monument was built there.

A year later, on December 30, 1913, the monument was officially opened. It was designed by Swiss sculptor Richard Kissling.

Works and Writings

Rizal mostly wrote in Spanish, which was the main language in the Philippines at that time. Some of his letters were in Tagalog. His works have been translated into many languages, including Tagalog and English.

Novels and Essays

- "El amor patrio" (Love of Country), 1882 essay

- "Toast to Juan Luna and Felix Hidalgo", 1884 speech

- Noli Me Tángere, 1887 novel (meaning 'touch me not')

- "Sa Mga Kababaihang Taga-Malolos" (To the Young Women of Malolos), 1889 letter

- Notes on Antonio de Morga's Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas, 1889

- "Filipinas dentro de cien años" (The Philippines a Century Hence), 1889–90 essay

- "Sobre la indolencia de los filipinos" (The Indolence of Filipinos), 1890 essay

- El filibusterismo, 1891 novel; the sequel to Noli Me Tángere

Poetry

- "El embarque" (The Embarkation, 1875)

- "Por la educación recibe lustre la patria" (1876)

- "Un recuerdo á mi pueblo" (1876)

- "A la juventud filipina" (To the Philippine Youth, 1879)

- "Canto de María Clara" (from Noli Me Tángere, 1887)

- "Himno al trabajo" (Hymn to Labor, 1888)

- "Mi retiro" (My Retreat, 1895)

- "Mi último adiós" (My Last Farewell, 1896)

Plays

- El Consejo de los Dioses (The Council of Gods)

- Junto al Pasig (Along the Pasig)

Other Works

Rizal also painted and sculpted. His most famous sculpture is The Triumph of Science over Death. It shows a young woman holding a torch, standing on a skull. The woman represents knowledge, and the torch represents how science brings light to the world. The skull represents death, showing how science helps overcome it.

The original sculpture is at the Rizal Shrine Museum in Fort Santiago, Manila. A large copy stands in front of the College of Medicine at the University of the Philippines Manila. Rizal was also a carver and sculptor who worked with clay, plaster, and wood. He made 56 sculptures, and 18 of them still exist today.

Reactions After Death

"Mi último adiós"

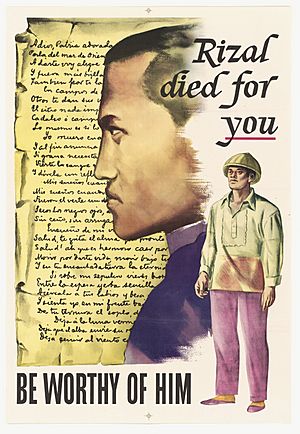

Rizal's famous farewell poem is also known as "Adiós, Patria Adorada" (Farewell, Beloved Fatherland). It was first printed in Hong Kong in 1897.

Six years after his death, the poem was translated into English and read in the United States Congress. This helped pass a law called the Philippine Organic Act of 1902. This law created the Philippine legislature and gave Filipinos more rights. It set the stage for the Philippines to become independent later. The poem has inspired people fighting for independence in other countries too.

Later Life of Josephine Bracken

Josephine Bracken, Rizal's partner, joined the Philippine Revolution after his death. She helped the revolutionary forces in Cavite province. She reloaded cartridges for General Pantaleón García. She later returned to Hong Kong and married another Filipino, Vicente Abad. Josephine died in Hong Kong in 1902 from tuberculosis. Rizal mentioned her in the last part of his poem, "Mi Ultimo Adios," calling her "Farewell, sweet stranger, my friend, my joy...".

Legacy and Remembrance

Rizal lived at the same time as other great leaders like Gandhi and Sun Yat Sen. Like them, he believed in achieving freedom peacefully. In his novel Noli Me Tángere, he suggested that if European rule had nothing better to offer, then colonialism in Asia was bound to fail.

As a political figure, José Rizal started La Liga Filipina. This group later led to the Katipunan, a secret society that began the Philippine Revolution against Spain. Rizal believed in peaceful self-government through reforms. He would only support "violent means" as a last resort. He said, "Why independence, if the slaves of today will be the tyrants of tomorrow?" This shows he wanted true freedom, not just a change of rulers.

Historians believe that Rizal gave the Philippine revolution a truly national spirit. His love for his country and his intelligence inspired others to value national identity.

Many honors have been given to him, such as "the First Filipino" and "Greatest Man of the Brown Race." The Knights of Rizal, a group that honors him, has chapters around the world. Some religious groups even see Rizal as a saint.

Animals Named After Rizal

When José Rizal was exiled in Dapitan, he spent time studying nature. He collected many different kinds of animals, insects, and plants. He sent these specimens to a museum in Dresden, Germany. He didn't want money; he only wanted scientific books and tools for his work.

Rizal even secretly sent some flying dragons to Europe. He thought they were a new species. A German zoologist named them Draco rizali after him. However, it was later found that this species had already been named.

Three animal species that Rizal collected were named after him:

- Draco rizali – a small lizard, also called a flying dragon.

- Apogonia rizali – a very rare beetle with five horns.

- Rhacophorus rizali – a unique frog species.

There are also at least five other species found in the Philippines that are named in his honor:

- Aedes rizali - a mosquito

- Conus rizali - a sea snail

- Hogna rizali - a spider

- Kalayaan rizali - a mite

- Spathomeles rizali - a beetle

Historical Commemoration

- After Rizal's death, the Anthropological Society of Berlin honored him. They read a German translation of his farewell poem.

- The Rizal Monument now stands near where he was executed in Luneta, which is now called Rizal Park in Manila. The monument also holds his remains. It has an inscription that says: "I want to show to those who deprive people the right to love of country, that when we know how to sacrifice ourselves for our duties and convictions, death does not matter if one dies for those one loves – for his country and for others dear to him."

- In 1901, a district was renamed the Province of Rizal in his honor. Today, many towns, streets, and parks in the Philippines are named after him.

- Republic Act No. 1425, known as the Rizal Law, was passed in 1956. It requires all high schools and colleges to teach about his life and writings.

- Monuments honoring Rizal can be found in many cities around the world, including Madrid, Tokyo, Chicago, and Toronto.

- In Wilhelmsfeld, Germany, where he lived, there is a small park and a street named after Rizal.

- In Heidelberg, Germany, a part of the Neckar River is named after Rizal.

- In 2011, many activities were held to celebrate Rizal's 150th birthday.

- The London Borough of Camden placed a "Blue Plaque" at 37 Chalcot Crescent, where Rizal once lived.

- A ship of the United States Navy, the USS Rizal (DD-174), was named after him in 1918.

- The José Rizal Bridge and Rizal Park in Seattle are also named after him.

- On June 19, 2019, Rizal's 158th birthday, he was honored with a Google Doodle.

- The Philippine Navy has a frigate (a type of warship) named BRP Jose Rizal, which arrived in the Philippines in 2020.

-

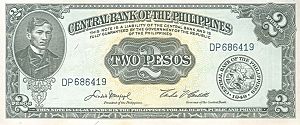

Rizal on the obverse side of a 1970 Philippine peso coin

-

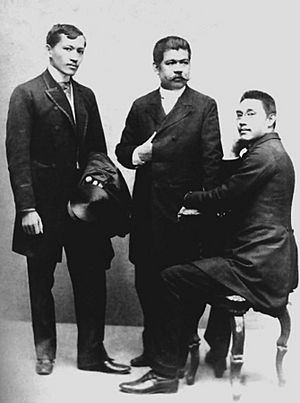

The Portrait of Rizal, painted in oil by Juan Luna

See also

In Spanish: José Rizal para niños

In Spanish: José Rizal para niños

- José Martí, Cuban national hero also executed by the Spanish in 1895