Marcelo H. del Pilar facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Marcelo H. del Pilar

|

|

|---|---|

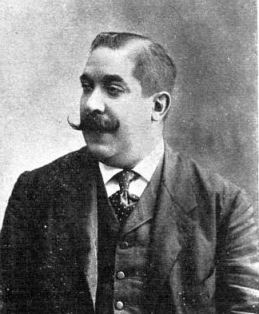

Del Pilar in Madrid, c. 1890

|

|

| Born |

Marcelo Hilario del Pilar y Gatmaitán

August 30, 1850 Bulakan, Bulacan, Captaincy General of the Philippines, Spanish Empire

|

| Died | July 4, 1896 (aged 45) |

| Resting place | Marcelo H. del Pilar Shrine, Bulakan, Bulacan |

| Nationality | Filipino |

| Other names | Pláridel (pen name) |

| Alma mater |

|

| Occupation |

|

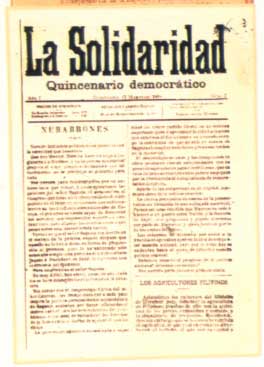

| Organization | La Solidaridad |

| Spouse(s) |

Marciana del Pilar

(m. 1878) |

| Children | 7 |

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

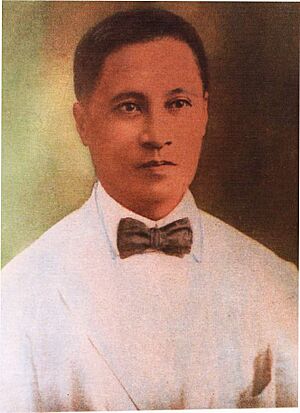

Marcelo Hilario del Pilar y Gatmaitán (Spanish: [maɾˈθe.lo iˈla.rjo ðel piˈlaɾ]; Tagalog: [maɾˈse.lo ɪˈla.rjo del pɪˈlaɾ]; August 30, 1850 – July 4, 1896), known as Marcelo H. del Pilar or by his pen name Pláridel, was a famous Filipino writer, lawyer, and journalist. He was also a freemason. Del Pilar, along with José Rizal and Graciano López Jaena, led the Reform Movement in Spain. This movement aimed to bring changes to the Philippines under Spanish rule.

Del Pilar was born in Bulakan, Bulacan. He was briefly jailed in 1869 after a disagreement with a priest about baptism fees. In the 1880s, he worked to expose problems with the friars (Spanish priests) in the Philippines. He moved to Spain in 1888 because he was ordered to leave the Philippines. A year later, he became the editor of La Solidaridad, a newspaper that promoted reforms. The newspaper stopped publishing in 1895 due to lack of money. Del Pilar began to lose hope in peaceful reforms and started to favor a revolution against Spain. He got tuberculosis in Barcelona while on his way home in 1896. He died in a public hospital and was buried in a simple grave.

In 1995, a government committee suggested that del Pilar be recognized as a National Hero. However, no official action has been taken yet.

Contents

Early Life and Education (1850–1880)

Marcelo H. del Pilar was born on August 30, 1850, in Bulacán, Bulacan. He was baptized a few days later. His family's original surname was "Hilario," but "del Pilar" was added later due to a Spanish naming rule.

Marcelo's parents were from the principalía, which meant they were a respected and wealthy family. They owned large farms and a mill. His father, Julián Hilario del Pilar, was a well-known writer and speaker. He also served as a town leader several times. Marcelo's mother, Blasa Gatmaitán, came from an old Tagalog noble family. Marcelo was one of their ten children.

From a young age, del Pilar learned to play musical instruments like the violin, piano, and flute. He also studied with his uncle and later at the Colegio de San Juan de Letran. He studied subjects like Poetry, Spanish grammar, and Latin grammar. He then went to the University of Santo Tomas to study Philosophy.

In 1869, del Pilar had an argument with a parish priest about high baptism fees. He was sent to prison for about a month but was later pardoned. After this, he continued his studies and earned his degree in Philosophy in 1871. He then began studying law.

While studying law, del Pilar also worked as a clerk in different towns. He finished his law degree in 1881. From 1882 to 1887, he worked as a defense lawyer. During this time, he actively spoke out about the problems in the Philippines. He attended many community events like weddings and fiestas. He used the Tagalog language to talk to ordinary people, including farmers and laborers. He shared his ideas about nationalism and love for the country. Many young students, like Mariano Ponce, listened to his talks and became his followers.

The Propaganda Movement in Spain (1888–1895)

Del Pilar arrived in Barcelona, Spain, on January 1, 1889. He became a leader in the Asociación Hispano-Filipina de Madrid, an organization of Filipinos and Spanish liberals. He wrote a letter to José Rizal, praising the brave young women of Malolos. These women had asked permission to open a night school to learn Spanish, even though a friar was against it. Del Pilar asked Rizal to write a letter to them in Tagalog to encourage them.

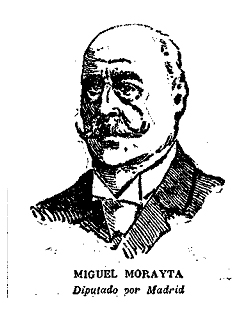

In April 1889, del Pilar met Miguel Morayta, a Spanish liberal who supported the Filipino cause. Morayta was a history professor and a Grand Master of Masons. Del Pilar and other Filipinos held a special dinner to honor Morayta.

Del Pilar worked to weaken the power of the friars in the Philippines. He supported a former friar, Nicolás Manrique Alonso Lallave, who had spoken out against the friars. Lallave wanted to open a Protestant church in Manila. Del Pilar tried to help him, but Lallave died of an illness. Some people believed the friars poisoned him.

On December 15, 1889, del Pilar took over from Graciano López Jaena as the editor of La Solidaridad. Under his leadership, the newspaper pushed for several goals:

- For the Philippines to become a province of Spain.

- To remove the friars and allow local priests to lead parishes.

- Freedom of assembly and speech.

- Equal rights for Filipinos under the law.

- For Filipinos to have representatives in the Spanish parliament (Cortes).

Del Pilar was a very active editor. He used many different pen names, like Pláridel, Dolores Manapat, and Piping Dilat, to write his articles.

In 1890, del Pilar worked with Francisco Calvo y Múñoz, a Spanish liberal, to get Philippine representation in the Cortes. Calvo y Múñoz proposed a change to a law that would allow Filipinos to elect three representatives. Important Spanish politicians like Manuel Becerra supported the idea but said it was too early to implement. Del Pilar continued to promote their speeches in La Solidaridad. However, the plan was put on hold when a new, more conservative Prime Minister took office in Spain.

In late 1890, a friendly competition arose between del Pilar and Rizal. This was because they had different ideas about how the Reform Movement should be led. In January 1891, Filipinos in Madrid decided to elect a leader. Rizal won the election, but he respectfully declined the position and gave it to del Pilar. Rizal then left Madrid and stopped writing for La Solidaridad.

Del Pilar apologized to Rizal for the disagreement. Rizal explained that he stopped writing to focus on his novel El filibusterismo and to allow other Filipinos to contribute. Del Pilar and Rizal continued to write to each other until Rizal was exiled to Dapitan in 1892.

Later in his life, del Pilar changed his mind about the Philippines becoming a province of Spain. He believed that assimilation was no longer the best path.

In 1892, a new Spanish government came to power. Del Pilar wrote articles in La Solidaridad, reminding the new leaders of their promises for reforms. While some laws were passed to improve local government in the Philippines, the idea of Filipino representation in the Spanish parliament was still ignored. Del Pilar then worked with Emilio Junoy, a friendly Spanish politician and newspaper editor. In 1895, Junoy presented a petition with thousands of signatures to the Cortes, asking for Philippine representation. He also gave a speech supporting a bill for this. Despite their efforts, the bill did not pass.

After years of publishing, La Solidaridad ran out of money. Del Pilar largely funded the newspaper himself. On November 15, 1895, he decided to stop its publication.

Later Years, Illness, and Death (1895–1896)

Del Pilar became very sick with tuberculosis in November 1895. The next year, he planned to return to the Philippines to lead a revolution. However, his illness got worse, and he couldn't travel. On June 20, 1896, he was taken to a hospital in Barcelona.

Del Pilar died on July 4, 1896, just over a month before the Cry of Pugad Lawin that started the Philippine Revolution. According to his friend Mariano Ponce, his last words were: "Please tell my family that I was not able to say goodbye, but that I died with my true friends around me… Pray to God for the good fortune of our country. Continue with your work to attain the happiness and freedom of our beloved country." He was buried the next day in a simple grave in Barcelona. Before he died, del Pilar left the Freemasons and received the last rites of the church.

Reactions After Death

- On July 15, 1896, a Spanish newspaper called La Politica de España en Filipinas praised del Pilar. They called him "the greatest journalist ever produced by the purely Filipino race."

- In 1897, former Governor-General Ramón Blanco described del Pilar as "the most intelligent leader, the real soul of the separatists, very superior to Rizal."

- In 1898, Mariano Ponce wrote that del Pilar was "a tireless propagandist" whose intelligence was respected even by his enemies.

Return of Del Pilar's Remains

In 1920, Norberto Romualdez was asked to find del Pilar's remains in Spain. With help, his body was dug up and placed in an urn. The ship carrying his remains arrived in Manila on December 3, 1920. His body was then taken to Malolos, Bulacan, and later to his birthplace in Bulakan, Bulacan.

A special service was held in Manila on December 12, 1920. Many important Filipino officials attended, including Manuel L. Quezon and Sergio Osmeña. Del Pilar's wife and two daughters were also there. After the service, del Pilar was buried in the Mousoleo de los Veteranos de la Revolución in the Manila North Cemetery.

On August 30, 1984, del Pilar's remains were moved again to his birthplace. They were laid to rest under his monument there.

Personal Life

Family

In February 1878, del Pilar married his second cousin, Marciana (Chanay), in Tondo. They had seven children: Sofía, José, María Rosario, María Consolación, María Concepción, José Mariano Leon, and Ana (Anita). Only Sofía and Anita, the oldest and youngest, lived to be adults. Anita later married Vicente Marasigan Sr. and had six children.

Challenges in Spain

Del Pilar faced extreme poverty during his last years in Spain. In a letter to his wife in 1892, he wrote that he had to borrow money for food every day. He even picked up cigarette butts to smoke. In another letter in 1893, he shared his frequent nightmares about his daughters, waking up in tears.

In June 1893, his relatives sent him money to return to the Philippines. However, his friends advised him to stay in Spain. He worried that a wrong move on his part could harm many people.

Health Issues

Before getting tuberculosis in 1895, del Pilar's health was already poor. He suffered from insomnia, dengue, influenza, rheumatism, and a neck tumor.

Connection with the Katipunan

Some historians believe that del Pilar played a direct role in the Katipunan's formation. This is because of his leadership in the Propaganda Movement and his high position in Philippine Masonry. Many of the Katipunan's founders and members were freemasons. The Katipunan even copied its initiation ceremonies from masonic rituals.

It is also said that Andrés Bonifacio, a leader of the Katipunan, was guided by del Pilar's letters. He considered them "sacred relics" of the revolution.

Testimonies from Katipuneros

Some members of the Katipunan claimed that del Pilar helped start the organization. However, some historians have questioned how accurate these statements are.

- Pío Valenzuela: On September 3, 1896, Pío Valenzuela stated that del Pilar was the President of the Katipunan's associates living in Spain.

- José Dizon: When the Katipunan was discovered, José Dizon was arrested. On September 23, 1896, he told Spanish authorities that Moisés Salvador brought instructions from Marcelo H. del Pilar in Madrid. He said Salvador passed these instructions to Deodato Arellano and Andrés Bonifacio.

- Águedo del Rosario: On June 28, 1908, Águedo del Rosario said that del Pilar had started the Katipunan. At that time, del Pilar was living in Barcelona.

Historical Remembrance

"Father of Philippine Journalism"

Marcelo H. del Pilar is widely known as the "Father of Philippine Journalism." This is because he wrote 150 essays and 66 editorials. Most of these were published in La Solidaridad and other anti-friar writings.

Samahang Plaridel, an organization for journalists, was founded in 2003. It honors del Pilar's ideas and helps Filipino journalists.

"Father of Philippine Masonry"

Del Pilar became a freemason in 1889. He was an active member of a lodge in Barcelona. He later became the leader of another lodge in Madrid.

Del Pilar worked to create Filipino Masonic lodges. In 1891, he sent someone to the Philippines to establish Nilad, the first Filipino Masonic lodge. In 1893, he also formed the Gran Consejo Regional de Filipinas, the first national group of Filipino Masons. Because of these efforts, he is called the "Father of Philippine Masonry."

The main building of the Masonic Grand Lodge of the Philippines in Manila is named Plaridel Masonic Temple after him.

Historical Commemoration

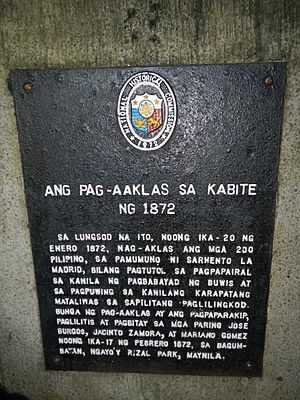

- The Marcelo H. del Pilar Shrine was built to honor him. It has a 10-foot monument and a museum library. The shrine is managed by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines.

- Monuments honoring del Pilar can be found in different places like Malolos, Paombong, and Parañaque.

- In 1969, a bronze statue of del Pilar was made by sculptor Anastacio Caedo.

- One corner of Plaza Miranda in Manila is named "Plaridel Corner" after him. It has a plaque with a famous quote: "I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it."

- Several towns in the Philippines are named "Plaridel" in his honor, including one in Bulacan, Misamis Occidental, and Quezon.

- A street in Manila, Marcelo H. del Pilar Street, is named after him. It used to be called Calle Real (Royal Street).

- The North Luzon Expressway (NLEX) was once known as the Marcelo H. del Pilar Superhighway.

- Marcelo H. del Pilar National High School in Malolos is named after him.

- A building at the Polytechnic University of the Philippines and the College of Mass Communication building at UP Diliman are also named after del Pilar.

- The U.P. Gawad Plaridel award, given to outstanding Filipino media professionals, is inspired by him.

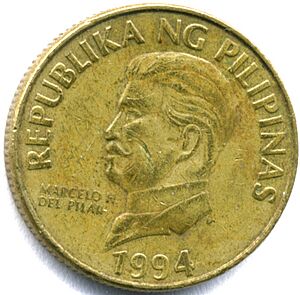

- Marcelo H. del Pilar was featured on the Philippine fifty centavo coin in different years.

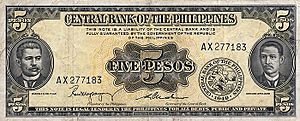

- Del Pilar and Graciano López Jaena appeared together on a five peso Philippine banknote from 1951 to 1974.

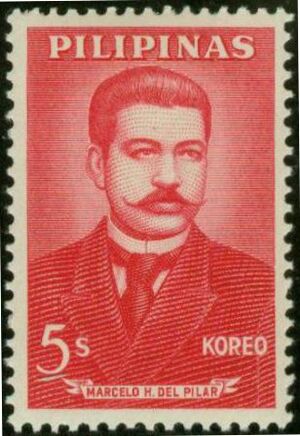

- A 5 centavo postage stamp featuring del Pilar was released in 1952.

- On April 27, 2022, President Rodrigo Duterte declared del Pilar's birth date as National Press Freedom Day.

Notable Works

Published During Del Pilar's Lifetime

- Ang Pagibig sa Tinubúang Lupà (Love for the Native Land, Tagalog translation of Rizal's El Amor Patrio, 1882)

- La Solídaridad (various articles and essays under pen names like Pláridel)

- En Filipinas Quien Manda? (Who is the Master in the Philippines?, 1887)

- El Monaquismo en Filipinas (Monasticism in the Philippines, 1888)

- Viva España! Viva el Rey! Viva el Ejército! Fuera los Frailes! (Long live Spain! Long live the King! Long live the Army! Throw the friars out!, 1888)

- Caiigat Cayó (Be as Slippery as an Eel, 1888)

- Ang Cadaquilaan nang Dios (The Greatness of God, 1888)

- Noli Me Tángere. Ante el Odio Monacal. (Noli Me Tangere. The Hatred of the Monks., 1888)

- Filipinas Ante la Opinion (The Philippines and Public Opinion, 1888)

- La Soberanía Monacal en Filipinas (Monastic Supremacy in the Philippines, 1888)

- Dasalan at Tocsohan (Prayers and Mockeries, 1888)

- Pasióng Dapat Ipag-alab nang Puso nang Tauong Babasa sa Calupitán nang Fraile (The Passion that Should Inflame the Hearts of Those Who Read About the Cruelty of the Friars, 1888)

- Relegacion Gubernativa (Governmental Relegation, 1889)

- La Asociación Hispano-Filipina (The Asociacion Hispano-Filipina, 1889)

- La Frailocracía Filipina (Friarocracy in the Philippines, 1889)

- Sagót nang España sa Hibíc nang Filipinas (Spain's Reply to the Cry of the Philippines, 1889)

- El Triunfo de la Remora en Filipinas (The Triumph of the Enemies of Progress in the Philippines, 1890)

- Prologo (Prologue of Filipinas en las Cortes, 1890)

- Arancel de los Derechos Parroquiales en las Islas Filipinas publicado con su traduccion tagala (Tagalog translation of Arancel de los Derechos Parroquiales en las Islas Filipinas, 1890)

- Exposicion de la Asociación Hispano-Filipina (Memorial of the Asociacion Hispano-Filipina, 1892)

- Para Rectificar (A Correction, 1892)

- Otro Peligro Colonial (Another Colonial Danger, 1895)

- Canal Bashi (The Bashi Channel, 1896)

- Ministerio dela República Filipina (Ministry of the Philippine Republic, 1896)

- La Patria (The Fatherland, 1896)

Published After His Death

- Dupluhan... Dalits... Bugtongs (A Poetical Contest in Narrative Sequence, Psalms, Riddles, 1907)

- Pagina Especial Para la Mujer Filipina (Special Page for the Filipino Woman, 1909)

Unpublished Works

- Sa Bumabasang Kababayan

- Discurso en El Meeting del Teatro Martin de Madrid (Speech at the Meeting in the Teatro Martin, Madrid)

- Esbozos de Un Codigo Internacional (Spanish translation of David Dudley Field's Outlines of an International Code)

- Proyecto de Estatutos de la Sociedad Financiera de Socorros Mutuos, Titulada la Paz (Proposed by-Laws of the Sociedad Financiera de Socorros Mutuos, Titulada la Paz)

- Reglas de Sintaxis Inglesa (Spanish translation of Rules of English Syntax)

- Progreso del Jefe Gomez: Rapida y Prontamente el Rebelde Principal Trastorna Todas las Combinaciones Españoles (The Progress of Chief Gomez: The Principal Rebel Leader Rapidly and Promptly Upsets All Spanish Combinations)

See also

In Spanish: Marcelo H. del Pilar para niños

In Spanish: Marcelo H. del Pilar para niños