1872 Cavite mutiny facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Cavite mutiny |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Philippine revolts against Spain and the aftermath of Spanish Revolution of 1868 | |||||||

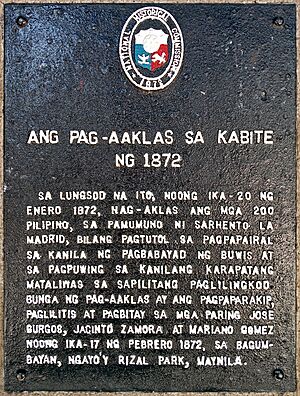

A historical marker installed in 1972 by the National Historical Commission at Samonte Park to commemorate the mutiny |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| One regiment, four cannons | Around 200 soldiers and laborers | ||||||

The Cavite Mutiny was a short uprising by Filipino soldiers and workers at Fort San Felipe, a Spanish military base in Cavite, Philippine Islands. This event happened on January 20, 1872. About 200 local soldiers and laborers took part. They hoped their actions would inspire a bigger movement across the country.

However, the uprising failed. Spanish government soldiers quickly stopped it. Many participants faced severe consequences. This event is seen by many as an important spark for Filipino nationalism, which later led to the Philippine Revolution.

Contents

Understanding the Cavite Mutiny

Many different reasons led to the Cavite Mutiny. Historians have looked at various accounts to understand what happened.

What Filipinos Said About the Mutiny

Trinidad Pardo de Tavera's View

According to Trinidad Pardo de Tavera, a Filipino scholar, the event was a simple uprising. He believed Filipinos at that time did not want to break away from Spain. They only wanted better living conditions and more educational opportunities.

However, Spanish friars saw the mutiny as a chance to regain power. The Spanish government in Madrid had reduced the friars' influence in local government and schools. Fearing they would lose all their power, the friars told the Spanish Governor-General that the mutiny was a large plot. They claimed it was a plan to end Spanish rule in the Philippines. The government in Madrid believed this story without fully investigating.

What the Spanish Said About the Mutiny

Spanish historian José Montero y Vidal believed the mutiny was a plan to remove Spanish rulers. His view was similar to that of Governor-General Rafael Izquierdo. Izquierdo was the Spanish governor of the Philippines during the mutiny. Both believed that Filipino priests were behind the uprising.

José Montero y Vidal's View

Montero y Vidal wrote that the mutiny was a plan by Filipinos to overthrow the Spanish government. He said it happened because workers at the Cavite arsenal lost special benefits. These benefits included not having to pay taxes and being free from forced labor (called polo y servicio).

He also mentioned that new ideas about democracy and freedom from Spain and America influenced Filipinos. These ideas, combined with the harsh rules of the Spanish governor, encouraged Filipinos to seek independence.

Governor-General Izquierdo's View

Governor-General Izquierdo claimed that Filipino priests, mixed-race individuals (mestizos), and lawyers started the mutiny. He said it was a protest against unfair government actions. These actions included not paying for tobacco crops, forcing people to pay taxes, and making them do forced labor.

Izquierdo believed the rebels planned to put a priest in charge of a new government. He thought José Burgos or Jacinto Zamora would be chosen as the leader, or 'pinuno'.

Other Views on the Mutiny

Edmund Plauchut's Account

Edmund Plauchut, a French writer, believed the immediate cause was a new order from Governor-General Izquierdo. This order made Filipino workers at the Cavite arsenal pay personal taxes. It also required them to perform forced labor, which they had previously been excused from.

On January 20, 1872, payday arrived. The workers found that taxes and fees for avoiding forced labor were taken from their salaries. This was the final straw. That night, they rebelled. About 60 soldiers and artillerymen took control of Fort San Felipe. They fired cannons to celebrate their success.

However, their victory was short-lived. The mutineers expected other Filipino soldiers in Cavite to join them. But these soldiers did not. Instead, they attacked the rebels. The mutineers then closed the fort gates, hoping for support from Manila.

Plauchut also noted that a revolution in Spain and new ideas about freedom reaching the Philippines contributed to the unrest. He mentioned that Filipino priests, who disliked the Spanish friars, were thought to have supported the rebels.

The Battle at Fort San Felipe

The leader of the mutiny was Fernando La Madrid, a sergeant of mixed Filipino and Spanish heritage. The rebels took over Fort San Felipe and killed eleven Spanish officers.

The mutineers thought Filipino soldiers in Manila would join their uprising. They planned to use rockets fired from Manila's city walls as a signal. Unfortunately, what they saw as a signal was actually fireworks for a religious festival in Sampaloc, Manila.

News of the mutiny quickly reached Manila. Spanish authorities became worried about a large Filipino uprising. The next day, a Spanish regiment led by General Felipe Ginovés surrounded the fort. The mutineers soon surrendered. General Ginovés then ordered his troops to fire at those who surrendered, including La Madrid. The remaining rebels were imprisoned.

Aftermath and Consequences

After the mutiny, some Filipino soldiers were disarmed. Many were sent away to the southern island of Mindanao. Those believed to have supported the mutineers were arrested.

The Spanish colonial government and friars used the mutiny to accuse three Filipino priests: Mariano Gomez, José Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora. They were known together as Gomburza.

The Execution of Gomburza

On February 15, 1872, Spanish authorities accused Fathers Burgos, Gomez, and Zamora of serious crimes against the government. They were sentenced to death by garrote (a method of execution) at Bagumbayan (now Luneta) in the Philippines. They were executed two days later, on February 17, 1872.

The accusation against the three priests was their supposed involvement in the uprising of workers at the Cavite Naval Yard. Governor-General Izquierdo believed that Filipinos planned to create their own government. He thought these three priests were nominated to lead it, aiming to break free from Spanish rule.

The deaths of Gomburza deeply angered many Filipinos. They demanded changes from the Spanish authorities. The execution of these three priests, though tragic, helped spark the Propaganda Movement. This movement aimed to seek reforms and inform the Spanish people about the unfair treatment of Filipinos in the Philippine Islands.

Other Punishments

On January 27, 1872, Governor-General Izquierdo approved death sentences for 41 mutineers. Later, 28 of them were pardoned, but the rest faced their sentences. On February 6, 1872, eleven more mutineers were sentenced to death, but their sentences were changed to life imprisonment.

Many other Filipinos were exiled to places like Guam in the Mariana Islands. Among them were Joaquin Pardo de Tavera, Antonio M. Regidor y Jurado, Pio Basa, and José María Basa. This group of exiled Filipinos formed communities in Europe, especially in Madrid and Barcelona, Spain. There, they started groups and published writings that helped push for the Philippine Revolution.

A new rule was also made, stopping further appointments of Filipinos as Catholic parish priests. Despite the mutiny, the Spanish authorities continued to use many Filipino troops, police, and civil guards in their forces until the Spanish–American War in 1898.

The Story Behind the Accusations

During the trials, some captured mutineers spoke against Father Burgos. A witness named Francisco Zaldua claimed that Father Burgos's "government" would bring a navy fleet to help a revolution. He also said Ramón Maurente was funding it with 50,000 pesos.

The leaders of the friar orders held a meeting. They decided to get rid of Burgos by linking him to the plot. One Franciscan friar reportedly pretended to be Burgos and suggested a mutiny to the rebels. The senior friars used a large sum of money or a banquet to convince Governor-General Izquierdo that Burgos was the main planner of the uprising. Since Gómez and Zamora were close to Burgos, they were also included in the accusations. Zaldua, the main informer against the three priests, was promised a pardon for his testimony. However, he was also executed along with them on February 17, 1872.

The Spanish government in Madrid wanted to reduce the friars' power in civil government and schools. The friars feared losing their influence. The mutiny gave them an opportunity to justify keeping their power. The Spanish government also introduced the Philippine Institute, aiming to improve education by requiring competitive exams for teaching jobs. This was a positive step welcomed by most Filipinos.

See also

In Spanish: Motín de Cavite para niños

In Spanish: Motín de Cavite para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |