José Martí facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

José Martí

|

|

|---|---|

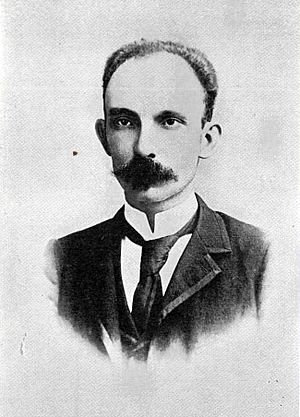

José Martí around 1892

|

|

| Born | José Julián Martí Pérez January 28, 1853 La Habana, Cuba (then ruled by Spain) |

| Died | May 19, 1895 (aged 42) Dos Ríos, Cuba (then ruled by Spain) |

| Occupation | Poet, writer, philosopher, nationalist leader |

| Nationality | Spanish and Cuban (after his death) |

| Literary movement | Modernismo (a literary style) |

| Spouse | Carmen Zayas Bazan Hidalgo |

| Children | José Francisco Martí Zayas Bazán (“Pepito”); María Mantilla |

| Relatives | Mariano Martí Navarro and Leonor Pérez Cabrera (Parents), 7 sisters (Leonor, Mariana, María de Carmen, María de Pilar, Rita Amelia, Antonia and Dolores) |

José Julián Martí Pérez (born January 28, 1853 – died May 19, 1895) was a Cuban nationalist, poet, philosopher, essayist, journalist, and publisher. He is known as a Cuban national hero because he played a big part in helping his country become free from Spain. He was also a very important person in Latin American literature.

Martí was very active in politics and is seen as a key philosopher and political thinker. Through his writings and political work, he became a symbol of Cuba's fight for independence from the Spanish Empire in the 1800s. People often call him the "Apostle of Cuban Independence." From a young age, he worked for liberty, Cuba's political independence, and for all Spanish American people to think freely. His death became a rallying cry for Cuban independence from Spain.

Born in Havana, which was then part of the Spanish Empire, Martí started his political work when he was young. He traveled a lot in Spain, Latin America, and the United States. He worked to make people aware of and support Cuba's independence. He brought together many Cubans living outside Cuba, especially in Florida. This was very important for the Cuban War of Independence against Spain. He helped plan and carry out this war. He also designed the Cuban Revolutionary Party and its ideas. He died in battle during the Battle of Dos Ríos on May 19, 1895. Martí is seen as one of the great thinkers of Latin America from the late 1800s. His writings include poems, essays, letters, speeches, a novel, and a children's magazine.

He wrote for many newspapers in Latin America and the United States. He also started several newspapers himself. His newspaper, Patria, was a key tool in his fight for Cuban independence. After he died, many of his poems from the book Versos Sencillos (Simple Verses) were used in the song "Guantanamera", which is now a famous Cuban song. Ideas like freedom, liberty, and democracy are big themes in all his works. His ideas influenced poets like Rubén Darío from Nicaragua and Gabriela Mistral from Chile. After the 1959 Cuban Revolution, Martí's ideas became a main force in Cuban politics. He is also known as Cuba's "martyr".

Contents

Life of a Cuban Hero

Early Years in Cuba: 1853–1870

José Julián Martí Pérez was born on January 28, 1853, in Havana, Cuba. His parents were from Spain. His father, Mariano Martí Navarro, was from Valencia, and his mother, Leonor Pérez Cabrera, was from the Canary Islands. José was the oldest of eight children, with seven younger sisters. When he was four, his family moved to Valencia, Spain, but they returned to Cuba two years later. José then went to a local public school.

In 1865, he joined a higher primary school led by Rafael María de Mendive. Mendive greatly influenced Martí's political ideas. His best friend, Fermín Valdés Domínguez, also helped him develop his social and political awareness. In April 1865, Martí and other students were very sad when they heard about the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, who had ended slavery in the United States. In 1866, Martí went to high school, with Mendive paying for his studies.

In September 1867, Martí enrolled in the Professional School for Painting and Sculpture in Havana to take drawing classes. He hoped to do well in art but did not find much success. In 1867, he also joined the San Pablo school, run by Mendive, where he continued his bachelor's degree and helped Mendive with school tasks. In April 1868, his poem for Mendive's wife appeared in a local newspaper.

When the Ten Years' War began in Cuba in 1868, groups supporting Cuban independence formed across the island. José and his friend Fermín joined them. Martí strongly desired Cuba's independence and freedom from a young age. He started writing poems about this dream and tried to make it happen. In 1869, he published his first political writings in a newspaper called El Diablo Cojuelo. That same year, he published "Abdala", a patriotic play in poetry form, in his own newspaper, La Patria Libre. "Abdala" is about a made-up country called Nubia that fights for freedom. His famous poem "10 de Octubre" was also written that year.

In March 1869, the Spanish authorities closed the school, stopping Martí's studies. He quickly grew to dislike Spanish rule in his homeland. He also hated slavery, which was still practiced in Cuba.

On October 21, 1869, when he was 16, Martí was arrested and put in jail. He was accused of treason after a letter he and Fermín wrote to a friend who joined the Spanish army was found. More than four months later, Martí admitted to the charges and was sentenced to six years in prison. His mother tried to free him by writing letters to the government, and his father sought legal help, but they failed. Martí became sick in prison, and his legs were badly hurt by the chains. Because of this, he was moved to another part of Cuba called Isla de Pinos. After that, the Spanish authorities decided to send him away to Spain. In Spain, Martí, who was 18, was allowed to continue his studies. The Spanish hoped that studying in Spain would make him loyal to Spain again.

Years in Spain: 1871–1874

In January 1871, Martí sailed from Havana to Cádiz, Spain. He settled in Madrid. There, he met Carlos Sauvalle, another Cuban who had been sent to Spain a year before. Sauvalle's house was a meeting place for Cubans living in exile. On March 24, a newspaper in Cádiz published Martí's article "Castillo," where he wrote about a friend's suffering in prison. This article was later printed in other cities like Sevilla and New York. At this time, Martí began studying law at the Central University of Madrid. While studying, Martí openly talked about Cuba's problems, writing in Spanish newspapers and sharing documents that protested Spain's actions in Cuba.

Martí's harsh treatment by the Spanish and his deportation to Spain in 1871 led him to write a pamphlet called Political Imprisonment in Cuba, published in July. This pamphlet aimed to make the Spanish public care about their government's cruelty in Cuba and support Cuban independence. In September, Martí and Sauvalle accused a newspaper of speaking badly about Cubans in Madrid. During his time in Madrid, Martí often visited libraries and cafes. In November, he became sick and had an operation.

On November 27, 1871, eight medical students were executed in Havana after being wrongly accused of disrespecting a Spanish grave. In June 1872, Fermín Valdés was arrested because of this event. His six-year prison sentence was pardoned, and he was sent to Spain, where he met Martí again. On November 27, 1872, a paper written by Martí and signed by Fermín Valdés Domínguez circulated in Madrid, remembering the executed students.

In 1873, Martí's poem "A mis Hermanos Muertos el 27 de Noviembre" (To My Brothers Dead on November 27) was published. In February, the Cuban flag appeared in Madrid for the first time, hanging from Martí's balcony. In the same month, the First Spanish Republic was declared, but it said Cuba was still part of Spain. Martí responded with an essay, The Spanish Republic and the Cuban Revolution. He sent it to the Prime Minister, pointing out that the new republic, which claimed to be based on democracy, was being unfair by not giving Cuba its independence. He sent his writings to Nestor Ponce de Leon, a member of the Central Revolutionary Committee of New York, showing his desire to help fight for Cuba's independence.

In May, he moved to Zaragoza with Fermín Valdés to continue his law studies. A newspaper in Sevilla published many of Martí's articles.

In June 1874, Martí earned his degree in Civil Law. In August, he began studying philosophy and literature, finishing his degree by October. In November, he returned to Madrid and then left for Paris. There, he met famous writers like Victor Hugo. In December 1874, he sailed from Le Havre to Mexico. Since he could not return to Cuba, Martí went to Mexico and Guatemala instead. During these travels, he taught and wrote, always speaking up for Cuba's independence.

Mexico and Guatemala: 1875–1878

In 1875, Martí lived in Mexico City. He became good friends with Manuel Antonio Mercado, a local official. On March 2, 1875, he published his first article for Revista Universal, a newspaper about politics, literature, and business. On March 12, his Spanish translation of Victor Hugo's book Mes Fils began to appear in the same newspaper. Martí then joined the newspaper's staff.

In his writings, he shared his thoughts on current events in Mexico. In May, he responded to anti-Cuban independence arguments in another newspaper. In December, a group of writers and artists accepted Martí as a member. Here, he met Carmen Zayas Bazán, who would become his wife.

In 1876, a civil war broke out in Oaxaca, Mexico. Martí and his Mexican friends started a group for writers and artists. Martí also began working with the newspaper El Socialista, supporting the government. In March, the newspaper suggested Martí as a delegate for a workers' congress. In December, Martí wrote an article criticizing the armed attack on the government. He then said goodbye to Mexico.

In 1877, Martí secretly went to Havana, hoping to move his family to Mexico City. He returned to Mexico, then traveled south to Guatemala City. He lived in a nice area where many artists lived. The government asked him to write a play called Patria y Libertad (Drama Indio) (Country and Liberty (an Indian Drama)). He met the president, Justo Rufino Barrios, about this project. In April, a newspaper published his article about new laws. In May, he was made head of the French, English, Italian, German Literature, History, and Philosophy Department at the National University. In July, he gave a speech at a literary society and was called "el doctor torrente" (Doctor Torrent) because of his powerful speaking style. Martí also taught free composition classes at a girls' academy. There, a young student named María García Granados y Saborío, the daughter of former president Miguel García Granados, fell in love with him. However, Martí went back to Mexico, where he met and later married Carmen Zayas Bazán.

In 1878, Martí returned to Guatemala and published his book Guatemala. On May 10, María García Granados died of lung disease. Her unrequited love for Martí led to her being sadly remembered as 'la niña de Guatemala, la que se murió de amor' (the Guatemalan girl who died of love). After her death, Martí returned to Cuba. He refused to sign the Pact of Zanjón, which ended the Cuban Ten Years' War but did not free Cuba from Spain. During this trip, he met Afro-Cuban revolutionary Juan Gualberto Gómez, who became his lifelong partner in the fight for independence. Martí married Carmen Zayas Bazán in Havana. In October, he was not allowed to practice law in Cuba. After this, he became deeply involved in revolutionary efforts. On November 22, 1878, his son José Francisco, known as "Pepito", was born.

Life in the United States and Venezuela: 1880–1890

In 1881, after a short time in New York, Martí went to Venezuela. In Caracas, he started the Revista Venezolana (Venezuelan Review). This journal angered Venezuela's leader, Antonio Guzmán Blanco, and Martí had to return to New York. There, Martí joined General Calixto García's Cuban revolutionary committee, made up of Cubans living in exile who wanted independence. Martí openly supported Cuba's fight for freedom. He worked as a journalist for La Nación in Buenos Aires and for several Central American newspapers. He also wrote poems and translated novels into Spanish. He worked for a publishing company and translated a book called Ramona. His own works included plays, a novel, poetry, a children's magazine called La Edad de Oro, and a newspaper called Patria. Patria became the official newspaper of the Cuban Revolutionary Party. He also served as a consul for Uruguay, Argentina, and Paraguay. Through all this work, he promoted "the freedom of Cuba with an enthusiasm that grew the number of people eager to work with him for it."

There was some tension within the Cuban revolutionary committee between Martí and the military leaders. Martí worried that a military dictatorship might take over Cuba after independence. He suspected General Máximo Gómez had such plans. Martí believed that Cuba's independence needed time and careful planning. In 1884, Martí refused to work with Máximo Gómez and Antonio Maceo Grajales, two Cuban military leaders from the Ten Years' War, when they wanted to invade Cuba right away. Martí knew it was too early to try to win back Cuba, and later events proved him right.

Travels and Organizing: 1891–1894

On January 1, 1891, Martí's important essay "Nuestra America" (Our America) was published in New York and Mexico. He also took part in the International Monetary Conference in New York. On June 30, his wife and son arrived in New York. After a short time, Carmen Zayas Bazán realized that Martí's dedication to Cuban independence was more important to him than supporting his family. She returned to Havana with their son on August 27. Martí never saw them again. It was a great personal sadness for Martí that his wife never shared his strong beliefs. He found comfort with Carmen Miyares de Mantilla, a Venezuelan woman who ran a boarding house in New York. It is believed he was the father of her daughter, María Mantilla, who later became the mother of actor Cesar Romero. In September, Martí became sick again. He spoke at events for Cuban independence, which led the Spanish consul in New York to complain to the Argentine and Uruguayan governments. Because of this, Martí resigned from his consul positions. In October, he published his book Versos Sencillos (Simple Verses).

On November 26, he was invited by the Club Ignacio Agramonte, a group of Cuban immigrants in Ybor City, Tampa, Florida. This was a fundraising event for Cuban independence. There, he gave a speech called "Con Todos, y para el Bien de Todos" (With All, and for the Good of All), which was printed in Spanish newspapers across the United States. The next night, Martí gave another speech, "Los Pinos Nuevos", in Tampa, honoring the medical students killed in Cuba in 1871. In November, an artist painted a portrait of José Martí.

On January 5, 1892, Martí attended a meeting of Cuban exile representatives in Cayo Hueso (Key West). There, the Bases del Partido Revolucionario (Basis of the Cuban Revolutionary Party) was approved. He began organizing this new party. To gain support and raise money for the independence movement, he visited tobacco factories. He gave speeches to the workers, uniting them for the cause. In March 1892, the first issue of the Patria newspaper, linked to the Cuban Revolutionary Party, was published. Martí funded and directed it. During Martí's years in Key West, his secretary was Dolores Castellanos, a Cuban-American woman born in Key West. She also led a Cuban women's political club that supported Martí's cause. Martí wrote a poem for her. On April 8, he was chosen as a delegate for the Cuban Revolutionary Party by clubs in Tampa and New York.

From July to September 1892, he traveled through Florida, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Jamaica. He was organizing Cubans living in exile. On this trip, Martí gave many speeches and visited various tobacco factories. On December 16, he was poisoned in Tampa.

In 1893, Martí continued traveling through the United States, Central America, and the West Indies, visiting different Cuban clubs. His visits were met with growing excitement and raised much-needed money for the revolution. On May 24, he met Rubén Darío, the Nicaraguan poet, in New York City. On June 3, he met with General Máximo Gómez in Montecristi, Dominican Republic, where they planned the uprising. In July, he met with General Antonio Maceo Grajales in San Jose, Costa Rica.

In 1894, he kept traveling to spread the word and organize the revolutionary movement. On January 27, he published "A Cuba!" in the Patria newspaper, where he spoke out against Spanish and American business interests working together. In July, he visited the president of Mexico, Porfirio Díaz, and traveled to Veracruz. In August, he prepared the armed expedition that would start the Cuban revolution.

Return to Cuba and Death: 1895

On January 12, 1895, U.S. authorities stopped three ships in Florida, seizing weapons and ruining the Fernandina Plan. On January 29, Martí wrote the order for the uprising, signing it with other leaders. Juan Gualberto Gómez was put in charge of preparing for war in Havana Province, working secretly under the Spanish authorities. Martí decided to go to Montecristi, Dominican Republic, to join Máximo Gómez and plan the uprising.

The uprising finally began on February 24, 1895. A month later, Martí and Máximo Gómez declared the Manifesto de Montecristi. This document explained the goals and ideas of the Cuban revolution. Martí had convinced Gómez to lead an expedition into Cuba.

Before leaving for Cuba, Martí wrote his "literary will" on April 1, 1895. He left his personal papers and writings to Gonzalo de Quesada y Aróstegui, with instructions on how to organize them. Martí knew that most of his newspaper writings would disappear over time. He asked Quesada to put his papers into volumes, organized by topic like North America, Hispanic America, literature, and poetry.

The expedition, including Martí, Gómez, and others, left Montecristi for Cuba on April 1, 1895. Despite delays, they landed at Playitas, Cuba, on April 11. Once there, they met with the Cuban rebels, led by the Maceo brothers, and began fighting against Spanish troops. The revolt did not go as planned because it did not get immediate support from many people. By May 13, the expedition reached Dos Rios. On May 19, Gómez's troops faced Spanish forces. Gómez told Martí to stay behind, but Martí got separated from the main Cuban forces and rode into the Spanish line.

Death in Battle

José Martí was killed in battle against Spanish troops at the Battle of Dos Ríos on May 19, 1895. Gómez saw that the Spanish had a strong position and ordered his men to pull back. Martí was alone and saw a young messenger ride by. He said: "Young man, charge!" It was around midday, and he was wearing a black jacket and riding a white horse, which made him an easy target for the Spanish. After Martí was shot, the young soldier, Angel de la Guardia, lost his horse and returned to report what happened. The Spanish took Martí's body, buried it nearby, then dug it up again when they realized who he was. He was buried in Santa Ifigenia Cemetery in Santiago de Cuba. Some people believe Martí rode into battle because others had criticized him for not fighting in combat. Some of his Versos Sencillos seem to predict his death:

"Do not bury me in darkness / to die like a traitor / I am good, and as a good man / I will die facing the sun."

Martí's death was a big blow to the hopes of the Cuban rebels, but the fighting continued until the United States entered the war in 1898.

Martí's Ideas and Beliefs

Fighting for Cuban Independence

Martí wrote a lot about Spain's control over Cuba and the danger of the United States expanding its power into Cuba. He believed it was wrong for Cuba to be controlled by Spain because Cuba had its own unique identity and culture. In his pamphlet from February 11, 1873, called "The Spanish Republic and the Cuban Revolution", he wrote that "Cubans do not live as Spaniards live.... They are fed by a different trade system, have links with different countries, and show their happiness through very different customs. There are no common hopes or goals linking the two peoples, or beloved memories to unite them."

Against Slavery

Martí was against slavery and criticized Spain for keeping it. In a speech to Cuban immigrants in New York on January 24, 1879, he said that the war against Spain had to be fought. He remembered the bravery and suffering of the Ten Years' War, which he said proved Cuba was a real nation with a right to independence. Spain had not kept its promises from the peace treaty, had rigged elections, continued to tax too much, and had not ended slavery. Cuba needed to be free.

Revolutionary Plans

In a letter to Máximo Gómez in 1882, Martí suggested forming a revolutionary party. He thought this was important to stop Cuba from falling back under Spanish rule after the Pact of Zanjón. He knew there were social divisions in Cuba, especially racial ones, that also needed to be fixed. He believed war was necessary to free Cuba, even though his main ideas were about peace, respect, and balance. He thought that creating a good government in Cuba would unite Cubans of all social classes and races.

Martí brought together many Cubans living outside Cuba, especially in Florida. This was key to planning and carrying out the invasion of Cuba. His speeches to Cuban tobacco workers in Tampa and Key West motivated and united them. This is seen as his most important political success. He developed his ideas, focusing on a Cuba united by pride in being Cuban, a society that would ensure "the well-being and success of all Cubans" no matter their class, job, or race. He believed the military should not take over. All Cubans who wanted independence would take part, with no group being more powerful than others. From these ideas, he started the Cuban Revolutionary Party in early 1892.

Martí and the Cuban Revolutionary Party secretly organized the war against Spain. Martí's newspaper, Patria, was a key part of this effort. In it, Martí explained his final plans for Cuba. He wrote against Spain's unfair control of Cuba, criticized other parties that did not want full independence, and warned against the U.S. taking over Cuba. He believed this could only be stopped if Cuba became truly independent. He described his plans for the future Cuban Republic: a democratic republic for all classes and races, based on fair voting, with an equal economy to develop Cuba's resources, and land shared fairly among citizens.

From Martí's diaries, it seems he would have held a very high position in the future Republic of Cuba. But he died before the Cuban Assembly was formed. Until his last moment, Martí worked to achieve full independence for Cuba. His strong belief in democracy and freedom for his homeland defined his political ideas.

Views on the United States

From a young age, Martí had an anti-imperialist view and believed that the United States could be a danger to Latin America. While he criticized the U.S. for its ideas about Latin Americans and its focus on capitalism, Martí also saw similarities between the American Revolution and Cuba's fight for independence. At the same time, he recognized good things about European and North American societies, which were open to changes that Latin American countries needed to break free from Spain's colonial past. Martí's distrust of U.S. politics grew in the 1880s because of threats of intervention in Mexico and Guatemala, which also affected Cuba's future. Over time, Martí became more worried about the United States' plans for Cuba. The U.S. needed new markets for its goods due to economic problems, and the media talked about buying Cuba from Spain. Cuba was a rich, fertile country with an important location in the Gulf of Mexico. Martí felt that Cuba's future should be with its sister nations in Latin America, not with the United States.

Martí also admired the strong work ethic in North American society. He often expressed deep respect for the immigrant society, which he saw as trying to build a truly modern country based on hard work and new ideas. Martí said he was "never surprised in any country of the world [he had] visited. Here [he] was surprised... [he] noticed that no one stood quietly on the corners, no door was shut an instant, no man was quiet. [He] stopped [him]self, [he] looked respectfully on this people, and [he] said goodbye forever to that lazy life and poetical uselessness of our European countries."

However, Martí did not admire everything in the United States. He wrote that U.S. politics had "become like a carnival... especially during election time." He saw corruption among candidates, such as bribing voters with beer, while big parades went through crowded streets. Martí criticized the powerful people in the United States who "pulled the main political strings behind the scenes." He believed these elites were the biggest threat to the "ideals with which the United States was first created."

Martí started to believe that the U.S. had misused its potential. Racism was common. Different races faced discrimination. Political life was seen as dishonest by the public and misused by "professional politicians." Rich business leaders and strong labor groups faced off against each other. All of this convinced Martí that a big social conflict was coming in the United States.

On the positive side, Martí was amazed by the "unbreakable right of freedom of speech that all U.S. citizens had." Martí praised the U.S. Constitution, which allowed freedom of speech to all its citizens, no matter their political beliefs. In May 1883, he attended political meetings where he heard "calls for revolution – and specifically the destruction of the capitalist system." Martí was surprised that the country allowed such speech, even if it could lead to its own destruction. Martí also supported the women's right to vote movements. He was "pleased that women here [took] advantage of this privilege to make their voices heard." According to Martí, free speech was essential for any nation to be civilized. He expressed his "deep admiration for these many basic freedoms and opportunities open to most U.S. citizens."

Martí's writings often compared life in North and Latin America. He saw North America as a "tough, 'soulless', and sometimes cruel society, but one that had been built on a strong foundation of liberty." Although North American society had its faults, they were "minor when compared to the widespread social inequality and abuse of power common in Latin America."

When it became clear that the United States planned to buy Cuba and make it more American, Martí "spoke out loudly and bravely against such actions." He shared the opinion of many Cubans about the United States.

Latin American Identity

José Martí believed that Latin American countries needed to understand their own history. He also saw the need for each country to have its own literature. These ideas began in Mexico in 1875. In his second "Boletin" published in Revista Universal (May 11, 1875), Martí's focus on Latin America was clear. His desire to build a national or Latin American identity was not new, but no other Latin American thinker at that time had approached it as clearly as Martí. He insisted on creating institutions and laws that fit each country's natural features. He pointed out that applying French and American laws to the new Latin American republics had failed. Martí believed that "el hombre del sur" (the man of the South) should choose a development plan that matched his character, unique culture, history, and nature.

Martí's Writings

Martí was a writer who worked in many different styles. Besides writing newspaper articles and many letters (which are part of his collected works), he wrote a novel that appeared in parts, composed poetry, wrote essays, and published four issues of a children's magazine, La Edad de Oro (The Golden Age, 1889). His essays and articles fill more than fifty volumes of his complete works. His prose was widely read and influenced the Modernist writers, especially the Nicaraguan poet Rubén Darío, whom Martí called "my son" when they met in New York in 1893.

Martí did not publish many books during his life. He only released two small poetry notebooks and some political papers. Most of his vast writings were spread across many newspapers and magazines, in letters, diaries, and personal notes. Some were never published, and some are now lost. Five years after his death, the first volume of his collected works was published. A novel, Amistad funesta, which Martí had published under a fake name in 1885, appeared in this collection in 1911. In 1913, his third poetry collection, Versos Libres, which he had kept private, was also published. His Diario de Campaña (Campaign Diary) was published in 1941.

Throughout his career, he wrote for many newspapers. He started with El Diablo Cojuelo (The Limping Devil) and La Patria Libre (The Free Fatherland), both of which he helped start in Cuba in 1869. These showed his strong political commitment. In Spain, he wrote for La Colonia Española, in Mexico for La Revista Universal, and in Venezuela for Revista Venezolana, which he founded. In New York, he wrote for Venezuelan, Argentine, and Mexican newspapers, as well as The Hour from the U.S.

The first full collection of Martí's complete works began to appear in 1983. The complete collection of his poems was published in 1985.

Volume two of his Obras Completas includes his famous essay 'Nuestra America'. This essay covers many topics about Spanish America that Martí studied and wrote about. It shows that after Cuba, he was most interested in Guatemala, Mexico, and Venezuela. The different parts of this work cover general topics, international meetings, economic, social, and political issues, literature and art, farming and industry, immigration, education, relations with the United States and Spanish America, and travel notes.

Martí explained that he published "La edad de oro" (The Golden Age) "so that American children may know how people used to live, and how they live nowadays, in the United States and in other countries; how many things are made, such as glass and iron, steam engines and bridges and electric light; so that when a child sees a colored stone he will know why the stone is colored. ... We shall tell them about everything which is done in factories, where things happen which are stranger and more interesting than the magic in fairy stories. These things are real magic, more marvelous than any. ... We write for children because it is they who know how to love, because it is children who are the hope for the world."

Martí's "Versos Sencillos" was written "in the town of Haines Falls, New York, where his doctor sent him to get stronger 'where streams flowed and clouds gathered'." The poems in this work are "in many ways about his own life and allow readers to see Martí the man and the patriot and to understand what was important to him at a crucial time in Cuban history."

Martí's writings showed his social and political views. "Cultivo Una Rosa Blanca" (I Cultivate a White Rose) is one of his poems that highlights his hopes for a better society:

I cultivate a white rose

In July as in January

For the sincere friend

Who gives me his hand frankly

And for the cruel person who tears

out the heart with which I live,

I cultivate neither nettles nor thorns:

I cultivate a white rose

This poem clearly describes Martí's hopes for his homeland. In the poem, he says that no matter if a person is kind or cruel, he cultivates a white rose, meaning he remains peaceful. This matches his idea of bringing people together in Cuba through a shared identity, without caring about ethnic or racial differences. He believed this could happen if one treated an enemy with peace, just as one would treat a friend. The kindness of one person should be shared with everyone, regardless of personal disagreements. By following the message in "Cultivo Rosa Blanca", Martí's dream of Cuban unity could become real, creating a more peaceful society for future generations.

After his success in Cuban literature, José Martí continued to contribute his works to newspapers, magazines, and books that showed his political and social views. Because he died young, Martí could not publish a large collection of poetry. Even so, his literary contributions have made him a famous figure in literature, inspiring many writers and people in general to follow his path.

Writing Style

Martí's writing style is hard to put into one category. He used many aphorisms—short, wise sayings—and long, complex sentences. He is seen as a major contributor to the Spanish American literary movement called Modernismo. His articles combined elements of literary description, dramatic storytelling, and a wide view of events. His poetry contained "fresh and surprising images along with seemingly simple feelings." As a speaker, he was known for his flowing structure, powerful sayings, and detailed descriptions. More important than his style is how he used it to share his ideas, making "advanced" notions convincing. Throughout his writing, he referred to historical figures and events, and constantly used references to literature, news, and cultural matters. Because of this, he can be difficult to read and translate.

His desire to teach led him to create a magazine for children, La Edad de Oro (1889). It included a short essay called "Tres Heroes" (Three Heroes), which shows his talent for adapting his writing to his audience. In this case, he wanted to make young readers aware of and amazed by the great bravery of three men: Bolivar, Hidalgo, and San Martín. This was his way of teaching in a delightful manner.

Translation Work

José Martí is honored as a great poet, patriot, and hero of Cuban Independence. But he was also a notable translator. While he translated literary works for enjoyment, much of his translation work was done out of financial need during his many years of exile in the United States. Martí learned English at a young age and began translating at thirteen. He continued translating throughout his life, including his time as a student in Spain. However, he was most productive during his stay in New York from 1880 until he returned to Cuba in 1895.

In New York, he worked as a freelancer and also as an "in-house" translator. He translated several books for the publishing house D. Appleton, and did many translations for newspapers. As a revolutionary activist in Cuba's long fight for independence, he translated many articles and pamphlets supporting the movement into English. Besides fluent English, Martí also spoke French, Italian, Latin, and Classical Greek fluently. He learned Greek so he could read the Greek classical works in their original language.

Martí had mixed feelings about the type of work he translated. Like many professionals, he took on translation jobs for money that he didn't find intellectually or emotionally appealing. Although Martí never wrote a full theory of translation, he did occasionally write down his thoughts on the subject. He was aware of the translator's challenge of being faithful to the original versus making it beautiful. He stated that "translation should be natural, so that it appears that the book was written in the language to which it has been translated."

Martí's Lasting Impact

Symbol of Cuban Independence

Martí's dedication to Cuban independence and his strong belief in democracy and justice have made him a hero for all Cubans. He is a symbol of unity, known as the "Apostle" and a great leader. His writings have created a record of all he experienced during that time. His main goal was to build a democratic, fair, and stable republic in Cuba. His focus on making this goal happen led him to become the most inspiring leader of the 1895 revolution against colonial rule. His work in rallying the Cuban community, raising money, settling disagreements among important revolutionary leaders, and creating the Cuban Revolutionary Party to organize this effort, started the Cuban War of Independence. His ability to see into the future, shown in his warnings against American political interests in Cuba, was proven right by the quick occupation of Cuba by the United States after the Spanish–American War. His belief that Cuban and Latin American freedom were connected, and how he expressed this in his writings, has helped shape the modern Latin American identity. Because of his beliefs, Cuba fought for its independence. His works are a key part of Latin American and political literature, and his many contributions to journalism, poetry, and prose are highly praised.

Influence on Cuban Politics

Martí was a classical liberal whose main goal was to free Cuba from Spain and create a democratic republican government. His writings about Cuban nationalism fueled the 1895 revolution. They have continued to shape different ideas about the Cuban nation.

Because the Cuban people greatly admired Martí, the communist government and Fidel Castro tried to connect themselves to the hero as much as possible. They supported his anti-imperialist views but ignored his writings that promoted individual freedom and criticized dictatorships. Even though Martí never supported communism or single-party systems, Cuban leaders often said Martí inspired them. They claimed that Martí's Partido Revolucionario Cubano was a "forerunner of the Communist Party." A clear example of this forced connection is that after his death in 2016, former Cuban leader Fidel Castro was buried next to Martí in Santiago.

Martí is seen as Cuba's "martyr" and "apostle." Many landmarks in Cuba are named after him. During Castro's time, Martí's politics and death were used to justify some government actions. The Cuban government claimed that Martí had supported a single-party system, creating a reason for a communist government. However, such claims are more about the communist government wanting to justify its actions by linking them to the national hero's ideas, rather than based on real evidence. There is no proof that Martí wanted a one-party system for Cuba. Instead, he admired democracy and the American republican system, and throughout his life, he strongly criticized any type of dictatorial government. He also criticized Karl Marx and warned about the dangers of socialism.

Martí's complex and sometimes mixed views on the important issues of his time have led some to see a class struggle in his works. Others have found a focus on liberal-capitalist ideas. Cubans who oppose the communist government honor Martí as a defender of freedom and democracy, and a symbol of hope for the Cuban nation. They criticize Castro's government for changing his works and creating a "Castroite Martí" to justify its "intolerance and limits on human rights." His writings therefore remain a key tool in the debate over Cuba's future.

Memorials and Tributes

José Martí International Airport, Havana's international airport, is named after Martí. A statue of Martí was revealed in Havana on his 123rd birthday, with President Raúl Castro attending. The José Martí Memorial in Havana includes a 109-meter tower and is the largest monument in the world dedicated to a writer.

The National Association of Hispanic Publications gives out the José Martí Awards each year for excellent Hispanic media.

In Cap-Haïtien, Haiti, a city José Martí visited three times, a power station is named after him. The house where he stayed during his last visit in 1895 has a marble plaque. Place José Martí (José Martí Square), with a bust of the poet, was opened in 2014.

Parque Amigos de José Martí is a small park in the Ybor City neighborhood of Tampa, FL. In 1956, the land was given to Cuba, and the park was officially opened in 1960. The park features a statue of Martí and a plaque from 1998. Near the park's entrance is another plaque marking the site of a boarding house where Martí recovered after being poisoned. About a block away is another historical marker remembering his unplanned speech to Cuban cigar workers from the steps of the Ybor Factory Building in 1893. The parks and markers are within the Ybor City Historic District.

The "White Rose" name of Germany's anti-Nazi resistance group (led by Sophie and Hans Scholl) from Munich university was reportedly inspired by Jose Martí's poem "Cultivo Una Rosa Blanca".

In Romania, a public school in Bucharest and the Romanian-Cuban Friendship Association in Targoviste are both named "Jose Martí".

In Shively, Kentucky, a bronze bust on a marble monument honors José Martí.

Selected Works by Martí

Martí's main works published during his life

- 1869: Abdala

- 1869: "10 de octubre"

- 1871: El presidio político en Cuba (Political Imprisonment in Cuba)

- 1873: La República Española ante la revolución cubana (The Spanish Republic and the Cuban Revolution)

- 1875: Amor con amor se paga (Love is Paid with Love)

- 1882: Ismaelillo (a poetry collection)

- 1882: Ryan vs. Sullivan

- 1882: Un incendio (A Fire)

- 1882: El ajusticiamiento de Guiteau (The Execution of Guiteau)

- 1883: "Batallas de la Paz" (Battles of Peace)

- 1883: "Que son graneros humanos" (That They Are Human Granaries)

- 1883: Karl Marx ha muerto (Karl Marx is Dead)

- 1883: El Puente de Brooklyn (The Brooklyn Bridge)

- 1883: "En Coney Island se vacía Nueva York" (New York Empties into Coney Island)

- 1883: "Los políticos de oficio" (Professional Politicians)

- 1883: "Bufalo Bil" (Buffalo Bill)

- 1884: "Los caminadores" (The Walkers)

- 1884: Norteamericanos (North Americans)

- 1884: El juego de pelota de pies (The Game of Football)

- 1885: Amistad funesta (Fatal Friendship)

- 1885: Teatro en Nueva York (Theater in New York)

- 1885: "Una gran rosa de bronce encendida" (A Great Bronze Rose Lit Up)

- 1885: Los fundadores de la constitución (The Founders of the Constitution)

- 1885: "Somos pueblo original" (We Are an Original People)

- 1885: "Los políticos tiene sus púgiles" (Politicians Have Their Fighters)

- 1886: Las revueltas anarquistas de Chicago (The Anarchist Riots of Chicago)

- 1886: "La ensenanza" (Teaching)

- 1886: "La Estatua de la Libertad" (The Statue of Liberty)

- 1887: El poeta Walt Whitman (The Poet Walt Whitman)

- 1887: El Madison Square (Madison Square)

- 1887: Ejecución de los dirigentes anarquistas de Chicago (Execution of the Anarchist Leaders of Chicago)

- 1887: La gran Nevada (The Great Snowfall)

- 1888: El ferrocarril elevado (The Elevated Railway)

- 1888: Verano en Nueva York (Summer in New York)

- 1888: "Ojos abiertos, y gargantas secas" (Open Eyes, and Dry Throats)

- 1888: "Amanece y ya es fragor" (Dawn Breaks and There is Already Roar)

- 1889: 'La edad de oro' (The Golden Age, a children's magazine)

- 1889: El centenario de George Washington (The Centennial of George Washington)

- 1889: Bañistas (Bathers)

- 1889: "Nube Roja" (Red Cloud)

- 1889: "La caza de negros" (The Hunting of Blacks)

- 1890: "El jardín de las orquídeas" (The Orchid Garden)

- 1891: Versos Sencillos (Simple Verses)

- 1891: "Nuestra América" (Our America)

- 1894: "¡A Cuba!" (To Cuba!)

- 1895: Manifiesto de Montecristi (Montecristi Manifesto) - co-authored with Máximo Gómez

Martí's major works published after his death

- Versos libres (Free Verses)

Images for kids

-

A monument of Jose Martí in Mexico City.

See also

In Spanish: José Martí para niños

In Spanish: José Martí para niños

- International José Martí Prize

- Radio y Televisión Martí

- José Rizal, a Philippine national hero also executed by the Spanish in 1896

- Bust of José Martí, Houston, Texas

- Monument to José Martí, Madrid, Spain

- Guantanamera

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |