Cuban War of Independence facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Cuban War of Independence |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

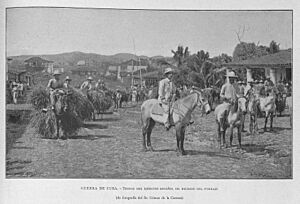

Photograph from the Battle of Ceja del Negro |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 53,774 | 196,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 5,480 killed 3,437 dead from disease |

9,413 killed 53,313 dead from disease |

||||||

| 300,000 Cuban civilians dead | |||||||

The Cuban War of Independence (Spanish: Guerra de Independencia cubana) was a major conflict fought from 1895 to 1898. It was the last of three wars where Cuba tried to gain freedom from Spain. The other two were the Ten Years' War (1868–1878) and the Little War (1879–1880). The final three months of this war turned into the Spanish–American War. During this time, the United States sent its forces to Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines to fight against Spain.

Historians still discuss why the United States got involved. Some say it was to help the Cuban people. Others agree that newspapers, especially those using "yellow journalism", made up or exaggerated stories about Spanish forces hurting Cuban civilians.

Contents

Why Did the War Happen?

After the Ten Years' War ended in 1878, Cuba had a period called the "Rewarding Truce" for 17 years. During this time, big changes happened in Cuban society. Slavery was ended in 1886, which meant many freed people became farmers or city workers. The economy struggled with these changes. Many rich Cubans lost their wealth and joined the middle class.

José Martí was a key Cuban leader. After being sent away from Cuba by Spain, he moved to the United States in 1881. There, he gathered support from Cubans living outside their homeland, especially in Florida. His main goal was to start a revolution to make Cuba independent from Spain. Martí also worked hard to stop the U.S. from taking over Cuba, which some politicians in both countries wanted.

Martí and other Cuban patriots formed "El Partido Revolucionario Cubano" (The Cuban Revolutionary Party). They worried that the U.S. might try to annex Cuba before they could free the island from Spain. Some U.S. leaders, like Secretary of State James G. Blaine, believed that Cuba should become part of the U.S. if it ever stopped being Spanish. Blaine wrote in 1881 that Cuba, being "the key to the Gulf of Mexico," should "necessarily become American." Martí saw this as a threat to a truly independent Cuba.

How the War Began

On December 25, 1894, three ships carrying soldiers and weapons left Florida for Cuba. Two of them were stopped by U.S. authorities. But this didn't stop Martí. On March 25, he wrote the Manifesto of Montecristi. This document explained the rules for Cuba's fight for independence:

- Everyone, both Black and White Cubans, should fight together.

- Black Cubans' involvement was very important for winning.

- Spaniards who did not oppose the war should not be harmed.

- Private farms and properties should not be destroyed.

- The revolution should bring new economic life to Cuba.

The rebellion officially started on February 24, 1895, with uprisings all over the island. The most important ones happened in the eastern part of Cuba, in places like Santiago de Cuba and Guantánamo. However, some uprisings in the central and western parts of the island failed because they were not well organized.

On April 1 and 11, 1895, important rebel leaders arrived in Cuba. Major General Antonio Maceo landed with 22 men, and José Martí landed with Máximo Gómez and four others. Spain had a large army in Cuba, about 80,000 soldiers, plus 60,000 local volunteers. By the end of 1897, Spain had 240,000 regular soldiers and 60,000 irregular troops on the island. The Cuban rebels were greatly outnumbered.

Who Were the Mambises?

The Cuban rebels were often called Mambises. The exact origin of this name is not fully known. Some say it came from a Dominican officer named Juan Ethninius Mamby who led rebels in the Dominican fight for independence in 1844. Others believe it comes from an African word, 'mbi', which meant 'outlaw'. At first, it might have been used as an insult, but the Cuban rebels proudly adopted the name for themselves.

From the beginning, the Mambises struggled because they didn't have many weapons. After the Ten Years' War, people were not allowed to own weapons. So, the rebels used guerrilla warfare. This meant they would attack quickly, surprise the Spanish troops, and then disappear into the environment. They often rode fast horses and used machetes against the Spanish soldiers. Most of their weapons and ammunition came from raids on the Spanish forces. It was very hard to get supplies from outside Cuba; out of 60 attempts between 1895 and 1897, only one succeeded.

Key Leaders and Strategies

José Martí was killed shortly after landing, on May 19, 1895. But Máximo Gómez and Antonio Maceo continued the fight, spreading the war across the eastern provinces. By the end of June, the entire region of Camagüey was involved in the war. These leaders made civilians choose sides: either move to areas controlled by the Cubans or be seen as supporting the Spanish.

In September, rebel leaders met in Jimaguayú, Camagüey. They created the "Jimaguayú Constitution" and set up a central government called the "Government Council." This council was led by Salvador Cisneros and Bartolomé Masó. The Cuban armies then moved west, tricking the Spanish army many times. They even defeated Spanish General Arsenio Martínez-Campos y Antón, who had won the Ten Years' War.

General Campos tried to stop the rebels by building a long defense line across the island called the trocha. This line was about 80 kilometers (50 miles) long and 200 meters (650 feet) wide. It had a railroad, fortifications, posts, barbed wire, and even booby traps. The idea was to keep the rebels stuck in the eastern provinces.

However, the rebels knew they had to take the war to the richer western provinces, where the government and wealth were. The Ten Years' War had failed partly because it stayed in the east. So, the revolutionaries launched a cavalry campaign, breaking through the trocha and invading every province. They reached the westernmost part of the island by January 22, 1896.

Spanish Response and Civilian Impact

General Campos was replaced by General Valeriano Weyler. Weyler tried to stop the rebels by forcing people to move. He ordered all people living in the countryside and their animals to gather in specific fortified towns controlled by his troops.

Hundreds of thousands of people had to leave their homes. They were forced into crowded towns and cities, living in terrible conditions. Historians estimate that between 155,000 and 170,000 civilians died because of these conditions, which was almost 10% of Cuba's population at the time.

During this period, Spain was also fighting a growing independence movement in the Philippines. These two wars put a huge strain on Spain's economy. In 1896, Spain refused secret offers from the United States to buy Cuba.

Antonio Maceo was killed on December 7, 1896, in Havana province. A big challenge for the Cuban rebels was getting enough weapons. Even though Cuban exiles and supporters in the U.S. sent weapons and money, many supply missions were stopped. Out of 71 missions, only 27 made it through.

By 1897, the Cuban liberation army controlled most of Camagüey and Oriente provinces, with Spain only holding a few cities. A Spanish leader admitted in May 1897 that even after sending 200,000 men, Spain didn't control much land on the island. The rebels, though fewer in number, won battles, like the Battle of La Reforma, and forced the surrender of Las Tunas, a well-defended town.

In October 1897, a second assembly of Cuban leaders met in La Yaya, Camagüey. They created a new constitution that stated military leaders would report to civilian leaders. Bartolomé Masó became President and Domingo Méndez Capote became Vice President.

Madrid tried to change its approach to Cuba. They replaced Weyler and offered Cuba and Puerto Rico a new colonial constitution and government. But by this point, the rebels controlled half the country and rejected these changes.

The Maine Incident

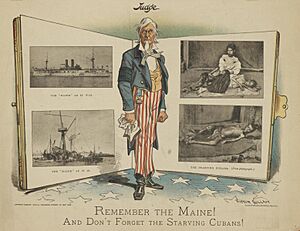

The Cuban fight for independence had caught the attention of many Americans for years. Some newspapers pushed for the U.S. to get involved, partly because of American businesses in Cuba. These newspapers often printed exciting, but sometimes exaggerated, stories about Spanish cruelty towards Cubans.

This kind of news continued even after Spain changed its policies and replaced Weyler. Many Americans felt strongly that the U.S. should help the Cubans.

In January 1898, a riot broke out in Havana by Cubans who supported Spain. They destroyed newspaper offices that had criticized the Spanish army. The U.S. Consul-General in Havana sent a message to Washington, worried about Americans living there. Because of this, the battleship USS Maine was sent to Havana in late January.

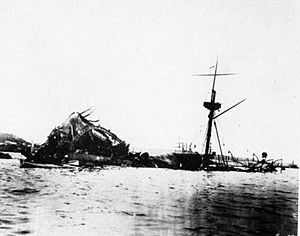

On February 15, 1898, the Maine exploded in Havana harbor, killing 260 crew members and sinking the ship. At the time, an investigation decided that a mine under the ship caused the explosion. However, later investigations suggested it might have been something inside the ship. The exact cause of the explosion is still not fully known today.

To try and calm the U.S., the Spanish government in Cuba agreed to two things President William McKinley had asked for: they stopped forcing people to move from their homes, and they offered to talk with the independence fighters. But the rebels refused this offer.

The Spanish–American War Begins

The sinking of the Maine made many Americans very angry. Newspaper owners like William Randolph Hearst quickly blamed Spanish officials in Cuba and spread this idea widely. In reality, Spain had no reason to want the U.S. to join the conflict. "Yellow journalism" (sensational news reporting) made American anger worse by publishing stories of "atrocities" by Spain in Cuba. One story says that when an artist told Hearst that conditions in Cuba weren't bad enough for war, Hearst replied, "You furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war."

President McKinley and many business leaders didn't want war. But public demand for war grew, fueled by the newspapers. The popular cry became, Remember the Maine, To Hell with Spain!

A key moment was a speech by Senator Redfield Proctor on March 17, 1898. He described the situation and said war was the only solution. After this, many businesses and religious groups changed their minds and supported war, leaving McKinley almost alone in opposing it.

On April 11, McKinley asked Congress for permission to send American troops to Cuba to end the civil war. On April 19, Congress passed a resolution supporting Cuban independence and saying the U.S. had no plans to take over Cuba. It demanded Spain leave Cuba and allowed the president to use military force to help the Cuban patriots. This resolution included the Teller Amendment, which stated that "the island of Cuba is, and by right should be, free and independent." It also said the U.S. would not control Cuba except to bring peace, and its armed forces would leave after the war. Congress officially declared war on April 25.

Some people believe a big reason for the U.S. war against Spain was the strong competition between Joseph Pulitzer's New York World and William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal. One historian wrote that the Spanish-American War might not have happened if Hearst hadn't started a fierce battle for newspaper sales in New York.

The fighting began hours after the declaration of war. U.S. Navy ships blocked several Cuban ports. The Americans decided to invade Cuba in the eastern part, where the Cubans had strong control. The Cubans helped by securing a landing spot for U.S. troops in Daiquiri. The first goal for the U.S. was to capture Santiago to defeat the Spanish army and navy there.

Between June 22 and 24, 1898, American troops under General William Rufus Shafter landed at Daiquirí and Siboney, east of Santiago, and set up a base. The port of Santiago became a main target for naval attacks. The U.S. fleet needed a safe harbor, so they attacked Guantánamo Bay on June 6. The Battle of Santiago de Cuba on July 3, 1898, was the biggest naval battle of the war, destroying the Spanish Caribbean fleet.

Major land battles between Spanish and American forces took place at Las Guasimas on June 24, and at El Caney and San Juan Hill on July 1, 1898, near Santiago. After these battles, the American advance slowed down. The Spanish troops defended Fort Canosa well, which helped them hold their ground and block entry to Santiago. The Americans and Cubans then began a difficult siege of the city, which finally surrendered on July 16.

With Oriente under American control, U.S. General Nelson A. Miles did not allow Cuban troops to enter Santiago. He said he wanted to prevent clashes between Cubans and Spaniards. Because of this, Cuban General Calixto García, who led the Mambi forces in the east, ordered his troops to stay in their areas. He resigned in protest, writing a letter to General Shafter about being excluded from entering Santiago.

Peace and Independence

After losing the Philippines and Puerto Rico, which the United States had also invaded, and with no hope of keeping Cuba, Spain decided to seek peace on July 17, 1898. On August 12, the United States and Spain signed a peace agreement. In this agreement, Spain agreed to give up all claims to Cuba. On December 10, 1898, the United States and Spain signed the Treaty of Paris. This treaty officially recognized Cuba's independence from Spain.

Even though Cubans had fought hard for their freedom, the United States did not allow Cuba to take part in the Paris peace talks or the signing of the treaty. The treaty did not set a time limit for the U.S. to occupy Cuba, and the Isle of Pines was not included as part of Cuba. The treaty officially granted Cuban independence, but U.S. General William Rufus Shafter did not allow Cuban General Calixto García and his rebel forces to participate in the surrender ceremonies in Santiago de Cuba.

See also

In Spanish: Guerra de Independencia cubana para niños

In Spanish: Guerra de Independencia cubana para niños

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |