Battle of Santiago de Cuba facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Santiago de Cuba |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish–American War | |||||||

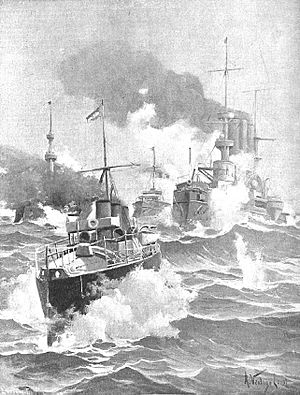

Combate en Santiago de Cuba, Ildefonso Sanz Doménech |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5 battleships 2 armored cruisers 2 armed yachts |

4 armored cruisers 2 destroyers |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1 killed 1 wounded 1 cargo ship sunk |

343 killed 151 wounded 1,889 captured 4 armored cruisers sunk 2 destroyers sunk |

||||||

The Battle of Santiago de Cuba was a major naval battle during the Spanish–American War. It happened on July 3, 1898, near Santiago de Cuba. The battle was fought between the United States Navy, led by Admirals William T. Sampson and Winfield Scott Schley, and the Royal Spanish Navy, led by Admiral Pascual Cervera y Topete.

The American fleet was much stronger. It had four battleships and two armored cruisers. The Spanish fleet had four armored cruisers and two destroyers. The American forces completely defeated the Spanish. All Spanish ships were sunk, and the Americans lost no ships. This huge victory helped the United States win the war in Cuba. It also helped Cuba become independent from Spanish rule.

Before the war, tensions grew between Spain and the United States. Many Americans were upset about how Spain was fighting the Cuban War of Independence. News reports, often exaggerated, talked about Spanish cruelty towards Cubans. In January 1898, the American ship USS Maine was sent to Havana to protect American interests. A month later, the Maine exploded in the harbor, killing 266 sailors. American newspapers blamed Spain, even though the real cause of the explosion was unclear. Two months later, the United States declared war on Spain.

American leaders knew they had to defeat the Spanish navy in Cuba to win the war. A fleet of six powerful American warships was sent to Cuba. On July 3, the Spanish fleet tried to escape from Santiago harbor. They were not ready for battle and were outgunned. The American battleships and cruisers chased them. The entire Spanish fleet was sunk. The Americans had very few casualties.

The Americans rescued 1,889 Spanish sailors, including Admiral Cervera. The captured Spaniards were treated with kindness. Admiral Cervera earned respect from American officers for his brave behavior. This battle secured the American victory in Cuba. It remains one of the most important naval battles in US maritime history.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

The Road to War

This battle was the end of a long struggle for Cuba's freedom from Spain. Cuba had been fighting for independence for many years. The United States had strong connections to Cuba through politics, business, and culture. Many American leaders and the public were upset by Spain's actions in Cuba.

Two main events made things worse. First, a private letter from a Spanish official, Enrique Dupuy de Lôme, was published. It criticized US President William McKinley. Americans saw this as an insult. Second, the American ship USS Maine exploded in Havana Harbor. Newspapers quickly blamed Spain. This fueled public anger and pushed the US towards war.

Spanish General Valeriano Weyler had created "reconcentrados" in Cuba. These were camps where Cubans from the countryside were forced to live. Many Cubans died there from disease and hunger. This policy made Spain look cruel to both Cubans and Americans.

Newspapers played a big role in shaping public opinion. In 1898, newspapers were the main source of news and entertainment. Journalists wrote exciting stories, often from the war zones. This made the public demand action.

In response to public outcry, President McKinley declared war on Spain on April 25. Some American leaders also saw the war as a chance to expand US territory. They wanted to show America's growing naval power. They also wanted to expand trade with Cuba, especially for sugar and tobacco.

Spain's Prime Minister, Práxedes Mateo Sagasta, did not want war. He knew Spain could not win against the US Navy. But he also knew his people would be angry if he gave in to American demands. Spanish naval leaders wanted to resist the US Navy as much as possible.

On May 1, 1898, the US Navy won a big victory against Spain at the Battle of Manila Bay in the Philippines. After this, Spain sent its fleet, led by Admiral Pascual Cervera y Topete, to Cuba. Their mission was to defend the island and keep supplies flowing to Spanish soldiers. Cervera thought his fleet was too weak for this mission. He wanted to fight near the Canary Islands or attack the American coast. But his leaders in Madrid overruled him. Cervera knew his fleet faced "total destruction."

The Spanish Fleet's Challenges

Admiral Cervera had been a military and political leader before the war. He was called back to lead the Spanish Caribbean Squadron. His fleet was supposed to reinforce Spanish forces in Cuba and defend the island. Before the war, Cervera had warned Spanish officials that their navy was weaker than the US Navy.

Another Spanish officer, Captain Fernando Villaamil, disagreed with Cervera. Villaamil thought Spain should spread out its fleet and attack quickly. But there was no clear plan, which made the Spanish navy's strategy uncertain.

On April 29, Cervera's fleet left Cape Verde. Americans worried about where his ships would go. They feared attacks on the US East Coast or American shipping. But Cervera managed to avoid the US fleet for weeks. He finally found safety in Santiago de Cuba harbor. On May 29, 1898, an American squadron found Cervera's newest ship, the cruiser Cristóbal Colón. The Americans immediately blocked the harbor entrance.

By early July, the Spanish were almost completely surrounded at Santiago. An American army of 16,000 soldiers was to the east. Cuban fighters were to the west. And the American fleet was to the south.

The Spanish squadron included the cruisers Almirante Oquendo, Vizcaya, Infanta Maria Teresa, and Cristóbal Colón. It also had the destroyers Plutón and Furor. These ships were about 7,000 tons each. But they were not heavily armored, and their weapons were not as strong as the Americans'.

Except for Cristóbal Colón, the cruisers had two 11-inch guns and ten 5.5-inch guns. Many Spanish guns had problems and would jam. Their ship boilers also needed repairs. Some ships, like Vizcaya, were slow because of biofouling (sea creatures growing on the hull). The Cristóbal Colón, the strongest Spanish ship, didn't even have its main guns installed. It sailed with wooden dummy guns instead!

Finally, Cervera's crews were not well trained. They lacked practice in shooting drills. Their training focused on firing quickly, while Americans aimed more carefully. The Spanish fleet was lightly armed due to budget cuts. This was also because Spain had focused on building smaller, faster ships to patrol its large empire.

With Cervera's fleet trapped, the top Spanish commander in Cuba, Ramon Blanco y Erenas, ordered them to leave the harbor. Cervera thought escape was almost impossible. He decided to sail out during the day to navigate the narrow channel safely. On July 3, 1898, Cervera, on his flagship Infanta Maria Teresa, led the Spanish fleet out of Santiago harbor.

The American Fleet's Strength

The American forces in Cuban waters were split into two groups. Rear Admiral William T. Sampson led the North Atlantic Squadron. Commodore Winfield Scott Schley commanded the "Flying Squadron." Together, they had more ships than the Spanish fleet. But their victory was also due to smart planning and better forces.

The American fleet had many types of ships. Sampson's flagship was the armored cruiser USS New York. Schley's flagship was the armored cruiser USS Brooklyn. These cruisers were well-armed. But the main power of the American fleet came from its battleships: USS Indiana, USS Massachusetts, USS Iowa, and USS Texas. These battleships were modern, steam-powered, and made of steel. They were built in the last ten years. The oldest was Texas, similar to the Maine that exploded in Havana.

These ships had 13-inch guns and could travel up to 17 knots (about 20 miles per hour). Off Santiago, Schley's "Flying Squadron" joined Sampson's larger fleet.

To make the fleet even stronger, US Navy Secretary John D. Long ordered the battleship USS Oregon to sail from California to the Caribbean. This ship traveled 14,500 nautical miles (about 16,700 miles) in 66 days. The Oregon had four 13-inch guns, eight 8-inch guns, and 18-inch thick steel armor. Its powerful engines made it very fast. Its speed and firepower earned it the nickname "bulldog of the Navy."

Besides battleships and cruisers, the Americans also used other ships. These included torpedo boats like USS Porter, light cruisers like USS New Orleans, and even a cargo ship called USS Merrimac. The Merrimac was sunk on June 3 to block the Spanish fleet inside the harbor.

The Standoff at Santiago

Sampson set up a semicircle blockade at the harbor entrance. An auxiliary ship waited nearby if a forced entry was needed. A torpedo boat guarded Sampson's flagship.

Life on blockade duty was long and boring. During the day, lookouts watched constantly. At night, a battleship shone a searchlight on the harbor entrance. This was to prevent the Spanish fleet from escaping in the dark. This routine went on for almost two months.

As long as Cervera stayed in Santiago Harbor, his fleet was relatively safe. The city's guns helped protect his ships. The area was also defended with sea mines and other obstacles. However, Cervera was still greatly outmatched. His ships were modern but too few. They also had many technical problems. There were no repair facilities in Santiago to fix his ships.

For over a month, the two fleets faced each other with only small fights. Cervera hoped bad weather would scatter the Americans, allowing him to escape. But US land forces began to attack Santiago de Cuba. By late June 1898, Cervera could no longer stay safely in the harbor. The Governor-General, Ramón Blanco y Erenas, ordered him to try to escape. He said it was "better for the honor of our arms that the squadron perish in battle."

The escape was planned for 9:00 a.m. on July 3. This seemed like the best time because the Americans would be at church services. Escaping at night would be too dangerous. By noon on July 2, the Spanish fleet was ready to go.

Around 8:45 a.m., Admiral Sampson and two of his ships, his flagship New York and the torpedo boat USS Ericsson, left their positions. They were going to a meeting with the US Army. This created a gap in the American blockade line. This gap gave Cervera a chance to escape. Sampson's New York was one of only two ships fast enough to catch Cervera if he broke through. Also, the battleship Massachusetts and the cruisers USS Newark and New Orleans had left that morning to get coal.

With Admiral Sampson gone, Commodore Schley on the armored cruiser Brooklyn took command. The blockade formation that morning included Schley's Brooklyn, followed by the battleships Texas, Oregon, Iowa, and Indiana. Also present were the armed yachts USS Vixen and Gloucester.

At 9:35 a.m., the navigator of Brooklyn saw smoke from the harbor mouth. He reported to Schley, "The enemy's ships are coming out!"

The Battle Begins

The Spanish ships started leaving the channel around 9:35 a.m. Admiral Cervera's flagship, Infanta Maria Teresa, led the way. It was followed by Vizcaya, Cristóbal Colón, and Almirante Oquendo. These ships were traveling at 8-10 knots (about 9-11 mph). The destroyers Plutón and Furor followed them. The Spanish ships then turned west towards the American fleet.

The battle started almost immediately. The American ships Texas, Iowa, Oregon, and Indiana fired heavily on the Spanish fleet. The first shot was fired by Iowa at 9:30 a.m. The Spanish fired back, supported by shore batteries.

Two things slowed the Spanish escape. First, Vizcaya had trouble keeping its speed. Second, most of the Spanish coal was of poor quality. They had expected good coal, but it was captured by an American ship earlier.

The Brooklyn first headed straight for Infanta Maria Teresa. But it looked like they would crash, so Commodore Schley ordered a sharp turn. This turn almost caused a collision with the Texas. The Infanta Maria Teresa and Vizcaya then turned west. Cristóbal Colón and Almirante Oquendo followed. The battle became a chase.

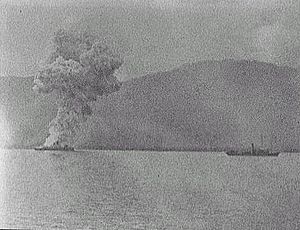

Admiral Cervera tried to protect his other ships. He engaged the Brooklyn directly while the rest of his fleet tried to escape. The Brooklyn was hit over 20 times but had only two casualties. Its return fire badly damaged Cervera's ship. The Infanta Maria Teresa caught fire. Cervera ordered it to run aground at 10:35 a.m. Admiral Cervera survived and was rescued by the crew of Gloucester.

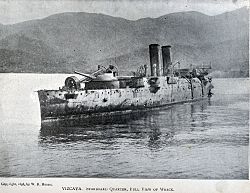

The rest of the Spanish fleet continued to flee. The Almirante Oquendo was hit 57 times. A shell exploding in a faulty gun turret destroyed it. A boiler explosion finished it off. It ran aground at 10:35 a.m., near the Infanta Maria Teresa.

Meanwhile, Plutón and Furor tried to escape in a different direction. The Gloucester fired heavily on them. The battleships Iowa, Indiana, and later New York also joined in. Furor sank at 10:50 a.m. Plutón ran aground at 10:45 a.m. Both destroyers lost two-thirds of their crew.

The Vizcaya fought a long gun battle with the Brooklyn for almost an hour. Even though they were close, most of the Spanish shots caused little damage. The Brooklyn pounded the Vizcaya with powerful fire. Historians later found that about 85% of Spanish ammunition was faulty or useless. The American ammunition worked perfectly. The Vizcaya was hit up to 200 times. A huge explosion happened, possibly from a torpedo being prepared. The Vizcaya was badly damaged and caught fire. It ran aground at 11:15 a.m.

American ships rescued Spanish survivors from the burning Vizcaya, Infanta Maria Teresa, and Almirante Oquendo. American sailors bravely went into danger to save the Spanish crews.

Only one Spanish ship, the fast armored cruiser Cristóbal Colón, was still afloat. It sped west, trying to escape. But it had a big problem: its main 10-inch guns had not been installed yet. It only had its smaller 6-inch guns. Speed was its only defense.

By the time Vizcaya was beached, Cristóbal Colón was almost six miles ahead of Brooklyn and Oregon. Cristóbal Colón could go about 15 knots (17 mph). The Brooklyn was slower because it only had two of its four engines running. The Oregon was the fastest American ship and began a long chase. The New York also raced to join the pursuit.

For 65 minutes, the Oregon chased Cristóbal Colón. The Spanish ship stayed close to the coast. It could not turn to the open sea because the Oregon was blocking its path.

Finally, three things ended the chase. Cristóbal Colón ran out of good coal and had to use lower quality coal. Also, a peninsula ahead would force it to turn south, right into Oregon's path. Lastly, the Oregon fired two 13-inch shells that landed right behind Cristóbal Colón.

The Cristóbal Colón turned towards the Turquino River and ran aground. Its crew opened valves to sink the ship and lowered their flag in surrender. Captain Cook of Brooklyn received the surrender. The Oregon tried to save the wreck of Cristóbal Colón, but it sank in shallow water.

American ships rescued as many Spanish survivors as possible. One Spanish officer, Captain Don Antonio Eulate of Vizcaya, was rescued by sailors from Iowa. He thanked his rescuers and offered his sword to Captain Robley Evans. Captain Evans returned the sword as a sign of respect.

By the end of the battle, the Spanish fleet was completely destroyed. Spain lost over 300 killed and 150 wounded out of 2,227 men. About 1,800 Spanish officers and men were taken prisoner. The American fleet lost only one killed and one wounded. Even though it was a huge victory, only 1-3% of American shots actually hit their targets.

After the Battle

The Battle of Santiago de Cuba marked a new beginning for the US Navy. It was a turning point in American and Spanish history. The defeat of the Spanish Navy gave the US control of the seas around Cuba. With no way to resupply their soldiers, Spain asked for peace and surrendered in August. The war was over.

Some of the surrender terms included:

- The United States would transport all Spanish forces in Cuba back to Spain.

- Spanish authorities would help the American Navy remove all mines and obstacles in Santiago de Cuba Bay.

- Spanish forces would leave Santiago de Cuba with military honors.

These terms were agreed upon in the Treaty of Paris (1898) in 1898. Spanish prisoners of war were sent to a camp in Maine. The Americans treated Spanish officers, soldiers, and sailors with great respect. They were later returned to Spain on American ships.

This battle ended Spain's important naval presence in the New World. It forced Spain to change its strategy in Cuba. The US control of the seas made it impossible for Spain to send supplies, leading to their surrender. Admiral Cervera was held in Annapolis, Maryland. He was welcomed with great enthusiasm there. The battle gave Cervera peace of mind that he had done his duty. His bravery earned respect from both Spanish and American sailors.

In the areas Spain left behind, the United States gained a lot of influence. The US took control of territories like Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. The US Navy grew stronger and became a global power. The Spanish–American War showed America's commitment to the Monroe Doctrine. This idea meant the US would act as a police force in the Western Hemisphere.

The victory also led to more American expansion. The US needed naval bases and coaling stations around the world. The Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico became US naval bases. However, local people in these new territories often resisted American rule. In the Philippines, this led to a war between local fighters and US forces. This was ironic because the US had fought to free Cuba from Spain, but now it was trying to control the Philippines. The Spanish–American War highlighted the conflict between American democracy and the desire for an empire.

Two of the Spanish ships, Infanta Maria Teresa and Cristóbal Colón, were later refloated by the US. Both eventually sank. The Reina Mercedes, left behind in Santiago Bay, was captured by the US Navy. It was used as a receiving ship until 1957.

Many flags and naval items from the Spanish ships are now at the U.S. Naval Academy Museum in Annapolis, Maryland. In 1998, for the 100th anniversary of the battle, the US Secretary of the Navy wanted to return the flag from the Spanish flagship Infanta Maria Teresa to the Spanish Navy. But the museum curator refused, citing a law from 1949 that gave the collection to the Naval Academy.

See also

In Spanish: Batalla naval de Santiago de Cuba para niños

In Spanish: Batalla naval de Santiago de Cuba para niños