History of Cuba facts for kids

The history of Cuba shows how the island has often depended on powerful countries like Spain, the U.S., and the USSR. Before Europeans arrived, different Native American groups lived on the island. In 1492, the explorer Christopher Columbus arrived on a Spanish trip. Spain then took control of Cuba and appointed Spanish governors to rule from Havana.

From 1868 to 1898, there were many rebellions against Spanish rule, but they didn't succeed. However, the Spanish–American War in 1898 led to Spain leaving the island. After three and a half years of U.S. military rule, Cuba became officially independent in 1902.

After gaining independence, the Cuban republic grew economically. But it also faced political problems and harsh leaders. This ended when Fulgencio Batista was overthrown by the 26th of July Movement, led by Fidel Castro, during the Cuban Revolution (1953–1959). The new government became friends with the Soviet Union and adopted communism. In the early 1960s, Castro's government survived an invasion (the Bay of Pigs Invasion in April 1961) and faced a major nuclear crisis (October 1962). During the Cold War, Cuba also supported Soviet policies in other countries. For example, Cuba's help in Angola helped Namibia gain independence in 1990.

The Cuban economy relied heavily on money from the Soviet Union. When the Soviet Union broke apart in 1991, Cuba faced a severe economic crisis called the Special Period. This crisis ended around 2000 when Venezuela started providing Cuba with cheaper oil. In 2019, Miguel Díaz-Canel became President of Cuba. The United States has isolated Cuba politically and economically since the Revolution. However, Cuba has slowly started to connect more with other countries as diplomatic relations improve.

Contents

- Early History (Before 1500)

- Spanish Arrival and Early Rule (1492 - 1800)

- Arrival of African Slaves (1500 - 1820)

- Cuba Under Attack (1500 - 1800)

- Changes and Independence Efforts (1800 - 1898)

- Conflicts in the Late 19th Century (1886 - 1900)

- U.S. Occupation (1898 - 1902)

- Early 20th Century (1902 - 1959)

- Castro's Cuba (1959 - 2006)

- Recent History (from 1991)

- See also

Early History (Before 1500)

The first people known to live in Cuba arrived around 4,000 years BC. The oldest known site, Levisa, is from about 3100 BC. More sites from after 2000 BC show cultures like Cayo Redondo and Guayabo Blanco in western Cuba. These groups used tools made from stone and shells. They lived by fishing, hunting, and gathering wild plants.

Before Columbus arrived, the native Guanajatabey people were pushed to the far west of the island. This happened as new groups, like the Taíno and Ciboney, arrived. These people had traveled north through the Caribbean islands.

The Taíno and Siboney were part of a larger group called the Arawak. They lived in parts of South America before Europeans came. They first settled in eastern Cuba and then spread across the island. A Spanish writer, Bartolomé de las Casas, thought that about 350,000 Taíno lived in Cuba by the late 1400s. The Taíno grew yuca root and made cassava bread. They also grew cotton and tobacco, and ate maize and sweet potatoes.

Spanish Arrival and Early Rule (1492 - 1800)

Christopher Columbus arrived in Cuba on October 27, 1492, during his first trip to the Americas for Spain. He was looking for a route to India and thought Cuba was part of Asia. He landed on October 28, 1492, at Puerto de Nipe.

On a second trip in 1494, Columbus explored the southern coast of Cuba. The Pope, Pope Alexander VI, ordered Spain to conquer and convert the native people of the New World to Catholicism. Columbus described the Taíno homes as "looking like tents in a camp. All were of palm branches, beautifully constructed."

The Spanish started building settlements on the island of Hispaniola, east of Cuba, soon after Columbus arrived. But Europeans didn't fully map Cuba's coast until 1508. In 1511, Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar came from Hispaniola to create the first Spanish settlement in Cuba, in Baracoa. The local Taíno people fought back strongly, led by their chieftain Hatuey. Hatuey had moved from Hispaniola to escape harsh Spanish rule there. After a long fight, Hatuey and other leaders were captured and killed. Within three years, Spain controlled the island. Havana was founded in 1519.

The Spanish clergyman Bartolomé de las Casas saw many massacres by the Spanish. For example, near Camagüey, about three thousand villagers who came to greet the Spanish were killed without reason. The native groups who survived fled to the mountains or small islands. They were later captured and forced into reservations, like Guanabacoa, which is now part of Havana.

In 1513, King Ferdinand II of Aragon created the encomienda system. This system gave Spanish settlers land and the right to use native people for labor. Velázquez, who became Governor of Cuba, was in charge of this. However, the system didn't work well. Many native people died from diseases like measles and smallpox brought by the Spanish. Others refused to work and escaped into the mountains. The Spanish then looked for slaves from nearby islands and the mainland. But these new arrivals also died from disease or escaped.

Despite the difficulties, some cooperation happened. Native people taught the Spanish how to grow tobacco and smoke it as cigars. Many Spanish men also had families with native women. Today, some Cuban families still have DNA traces similar to Amazonian tribes. The native population and their culture largely disappeared after 1550. However, some indigenous Cuban families still live in eastern Cuba. About 400 Taíno words and place-names, like "Cuba" and "Havana," are still used today.

Arrival of African Slaves (1500 - 1820)

Spain made sugar and tobacco Cuba's main products. Cuba soon became Spain's most important base in the Caribbean. More workers were needed, so African slaves were brought to work on the plantations. However, strict Spanish trade laws made it hard for Cuba to keep up with new ways of processing sugar cane that were being used in other islands. Spain also limited Cuba's access to the slave trade.

In the 19th century, Cuban sugar plantations became the world's most important sugar producers. This was thanks to more slavery and new sugar technology. Modern refining techniques became very important because Britain abolished the slave trade in 1807. Under pressure from Britain, Spain agreed to end the slave trade from 1820. Cubans quickly imported over 100,000 new slaves between 1816 and 1820 before the ban. Even after 1820, a large illegal slave trade continued.

Many Cubans felt conflicted about slavery. They wanted the profits from sugar but disliked slavery, seeing it as morally wrong and dangerous for their society. Slavery was finally abolished by the end of the 19th century. Before that, Cuba became very rich from its sugar trade. New technology, like water mills and steam engines, helped produce sugar faster and better.

The growth of Cuba's sugar industry in the 19th century also led to better transportation. New roads and railroads were built to move sugar from plantations to ports quickly. This made it easier for plantations across the large island to ship their sugar.

Sugar Plantations

Cuba didn't grow much economically before the 1760s because Spain controlled trade very strictly. Spain wanted to protect its trade routes and slave trade routes. This stopped Cuba from trading with foreign ships.

Once Spain opened Cuba's ports to foreign ships, a huge sugar boom began, lasting until the 1880s. Cuba was perfect for growing sugar, with its flat lands, rich soil, and enough rain. By 1860, Cuba focused almost entirely on sugar, importing everything else it needed. Cuba relied especially on the United States, which bought 82% of its sugar.

Cuba Under Attack (1500 - 1800)

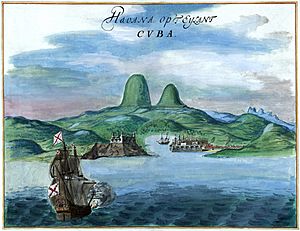

Colonial Cuba was often attacked by buccaneers, pirates, and French privateers who wanted Spain's riches. To stop these attacks, defenses were built across the island in the 16th century. In Havana, the Castillo de los Tres Reyes Magos del Morro fortress was built. Even the English privateer Francis Drake sailed near Havana but didn't land. However, Havana was still vulnerable. In 1628, a Dutch fleet attacked and robbed Spanish ships in the harbor. In 1662, the English pirate Christopher Myngs captured and briefly held Santiago de Cuba to open up trade.

Almost a century later, the British Royal Navy invaded again, taking Guantánamo Bay in 1741 during a war with Spain. The British admiral, Edward Vernon, had to withdraw his troops because of attacks by Spanish soldiers and a disease outbreak. The British also attacked Santiago de Cuba in 1741 and 1748, but failed.

The Seven Years' War reached the Spanish Caribbean in 1762. Spain was allied with France, putting them against Britain. A British force of warships and troops set out from Portsmouth to capture Cuba. They arrived on June 6 and besieged Havana by August. When Havana surrendered, the British admiral, George Keppel, became the new governor and took control of western Cuba. The British occupation quickly opened up trade with their North American and Caribbean colonies, changing Cuban society.

Havana, which was the third-largest city in the Americas, grew during this time. But the British occupation was short. Less than a year after Havana was taken, the Peace of Paris ended the Seven Years' War. Britain received Florida in exchange for Cuba. In 1781, Spanish General Bernardo de Gálvez recaptured Florida for Spain with help from Mexican, Puerto Rican, Dominican, and Cuban troops.

Changes and Independence Efforts (1800 - 1898)

In the early 1800s, three main political ideas emerged in Cuba: reformism (making changes while staying with Spain), annexation (joining the United States), and independence (becoming a separate country). There were also efforts to end slavery. The American and French Revolutions, and the successful slave revolt in Haiti in 1791, inspired early Cuban movements. One of the first, led by Nicolás Morales, aimed for equality and lower taxes. This plot was discovered in 1795.

Reform and Independence Movements

After Napoleon removed the Spanish king in 1808, a rebellion for independence started among wealthy Cubans in 1809-1810. One leader, Joaquín Infante, wrote Cuba's first constitution, declaring it a sovereign state. This plan also failed, and leaders were jailed or sent away. In 1812, a mixed-race group led by José Antonio Aponte planned to end slavery. They were executed.

The Spanish Constitution of 1812 brought some liberal policies, which Cubans liked. But the king, Ferdinand VII, ended these policies when he returned to power in 1814. This led to a rise in Cuban nationalism. Many secret societies formed, like the "Soles y Rayos de Bolívar" in 1821. This group wanted to create the free Republic of Cubanacán. Its leaders were arrested and exiled in 1823.

The king's harsh rule and the success of independence movements in other Spanish colonies in America made Cubans want their own country even more. Several independence plots happened in the 1820s and 1830s, but all failed.

Anti-Slavery and Independence Efforts

In 1826, the first armed uprising for independence happened in Puerto Príncipe. Its leaders, Francisco de Agüero and Andrés Manuel Sánchez, were executed. They became important figures in the Cuban independence movement.

In the 1830s, the reform movement grew, with leader José Antonio Saco criticizing Spain's harsh rule and the slave trade. But Spain increased its control.

Spain was under pressure to end the slave trade. In 1835, Spain signed a treaty promising to abolish slavery. This led to more slave revolts in Cuba, which were brutally put down. One major event was the "Ladder Conspiracy" in 1843-1844. Many people died from severe punishments or were executed, including the poet Gabriel de la Concepción Valdés.

After the Ten Years' War (1868–1878), slavery was completely abolished by 1886. Cuba was one of the last countries in the Western Hemisphere to do so. Instead of African slaves, workers were brought from China and Yucatán. Many Spanish-born people, called peninsulares, also lived in Cuba.

The Idea of Joining the United States

Some Cubans wanted Cuba to join the United States because slavery was still legal there, and they hoped for economic growth and freedom like in America. U.S. officials often suggested annexing Cuba. In 1805, President Thomas Jefferson thought about it for strategic reasons.

In 1823, U.S. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams said that Cuba, if it separated from Spain, would naturally join the United States. He also warned that Britain should not try to take Cuba. On December 2, 1823, President James Monroe's Monroe Doctrine warned European powers to stay out of the Americas. Cuba, being very close to Florida, was important to this idea.

General Narciso López tried four times to invade Cuba from the U.S. to achieve annexation. His first two attempts failed due to U.S. opposition. His third attempt landed in Cuba but failed due to lack of support. His fourth attempt in 1851 was defeated by Spanish troops, and López was executed.

The Fight for Independence

In the 1860s, Cuba had some more liberal governors. But then a strict governor, Francisco Lersundi, took away freedoms and supported slavery. On October 10, 1868, landowner Carlos Manuel de Céspedes declared Cuban independence and freedom for his slaves. This started the Ten Years' War (1868–1878). Many former Dominican soldiers who had served with Spain joined the Cuban rebels and helped train them.

With help, the Cuban rebels defeated Spanish groups, cut railway lines, and gained control of much of eastern Cuba. The Spanish government used harsh methods against the rebels, which only made more people join the fight. However, the revolution did not spread to western Cuba. Ignacio Agramonte was killed in 1873, and Céspedes was killed in 1874. In 1875, Máximo Gómez began to move westward, past a fortified line built by the Spanish to stop him.

Gómez was known for burning sugar plantations to hurt the Spanish. After American admiral Henry Reeve was killed in 1876, Gómez ended his campaign. By then, Spain had sent over 250,000 troops to Cuba. On February 10, 1878, Spanish General Arsenio Martínez Campos negotiated a peace treaty, the Pact of Zanjón, with the Cuban rebels. Rebel general Antonio Maceo surrendered on May 28, ending the war. Spain lost 200,000 soldiers, mostly to disease. The rebels lost 100,000–150,000 people. The treaty promised freedom to all slaves who fought for Spain, and slavery was legally abolished in 1880. However, unhappiness with the treaty led to the Little War in 1879–80.

Conflicts in the Late 19th Century (1886 - 1900)

Changes in Cuba

After the Ten Years' War, from 1878 to 1895, Cuban society changed a lot. When slavery ended in 1886, former slaves joined the working class. Many wealthy Cubans lost their land and became part of the urban middle class. The number of sugar mills decreased, but the remaining ones became more efficient. More farmers became tenants on land owned by others. Also, American money started flowing into Cuba, especially into sugar, tobacco, and mining. By 1895, these investments were worth $50 million. So, while Cuba was still politically Spanish, it became more economically dependent on the United States.

Labor movements also grew. The first Cuban labor organization, the Cigar Makers Guild, was created in 1878. At the same time, the U.S. became more interested in controlling Cuba. U.S. Secretary of State James G. Blaine believed that Cuba, if it ever stopped being Spanish, must become American.

Martí's Uprising and the War

After being sent away from Cuba a second time in 1878, pro-independence activist José Martí moved to the United States in 1881. He started gathering support from Cubans living in Florida. He wanted a revolution for Cuban independence from Spain. He also worked to prevent the U.S. from taking over Cuba.

On April 10, 1892, the Partido Revolucionario Cubano (Cuban Revolutionary Party) was officially formed to gain independence for Cuba and Puerto Rico. Martí was chosen as its leader. By late 1894, everything was ready for the revolution. Martí was eager to start because he feared the U.S. would annex Cuba before it could become free from Spain.

On December 25, 1894, three ships carrying armed men and supplies sailed for Cuba from Florida. Two were stopped by U.S. authorities in January, but the plans continued. The uprising began on February 24, 1895, with revolts across the island. Martí, on his way to Cuba, gave the Proclamation of Montecristi. This outlined the war's policy: blacks and whites would fight together, Spaniards who didn't oppose the war would be spared, and private property would not be damaged.

On April 1 and 11, 1895, the main rebel leaders, including Martí and Máximo Gómez, landed in eastern Cuba. At that time, Spain had about 80,000 soldiers in Cuba. By December, Spain had sent 98,412 regular troops, and the number of local volunteers grew to 63,000. By late 1897, there were 240,000 regular troops and 60,000 irregulars. The revolutionaries were greatly outnumbered.

The rebels were called "Mambis," a name they adopted with pride. Since weapons were banned for private citizens, the rebels faced a serious shortage of arms. They used guerrilla tactics, relying on the environment, surprise attacks, fast horses, and simple weapons like machetes. Most of their firearms were taken from the Spanish. Between 1895 and 1897, 60 attempts were made to bring weapons to the rebels from outside Cuba, but only one succeeded.

War Escalation

Martí was killed on May 19, 1895. But Máximo Gómez and Antonio Maceo continued the fight, spreading the war across eastern Cuba. Gómez used harsh tactics, like blowing up trains and burning Spanish loyalists' property and sugar plantations. By the end of June, all of Camagüey was at war. Gómez and Maceo moved west, joining other fighters and growing their forces. In September, rebel leaders met and approved the Jimaguayú Constitution, which set up a central government.

The rebels outsmarted the Spanish army many times. They defeated Spanish General Arsenio Martínez Campos, who had won the Ten Years' War. Campos tried to stop the rebels by building a large defensive line, called a trocha, across the island. This line had a railroad with armored cars, fortifications, posts, and barbed wire.

It was important for the rebels to bring the war to the western provinces, where the government and wealth were. The Ten Years' War had failed because it couldn't get past the eastern provinces. But in a successful campaign, the rebels crossed the trochas and invaded every province. They surrounded major cities and reached the westernmost tip of the island by January 22, 1896.

Unable to defeat the rebels with normal military tactics, the Spanish government sent General Valeriano Weyler (nicknamed The Butcher). He used severe methods: executions, mass exiles, and destroying farms and crops. On October 21, 1896, he ordered all countryside residents to gather in fortified areas. Hundreds of thousands of people had to leave their homes, leading to terrible overcrowding and conditions in towns. This was an early use of concentration camps to remove non-combatants and deprive the enemy of support. It's estimated that this policy caused the death of at least one-third of Cuba's rural population. This forced relocation lasted until March 1898.

Spain was also fighting an independence movement in the Philippines, which put a heavy strain on its economy. In 1896, Spain refused U.S. offers to buy Cuba.

Maceo was killed on December 7, 1896. The biggest challenge for the Cubans was getting weapons. Many weapons and funds came from the U.S., but these operations were often stopped by the U.S. Coast Guard.

By 1897, the rebels controlled much of Camagüey and Oriente. A Spanish leader admitted that Spain controlled little land on the island. The rebels, though outnumbered, defeated the Spanish in several battles. A new constitution was adopted in October 1897, placing military command under civilian rule. But with half the country out of its control, the new Spanish government was powerless and rejected by the rebels.

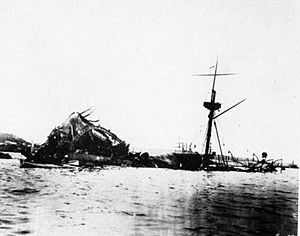

The USS Maine Incident

The Cuban fight for independence had captured American attention. Newspapers published sensational stories about Spanish actions against Cubans, making Americans believe Cuba's struggle was like their own Revolutionary War. Public opinion in the U.S. strongly favored helping the Cubans.

In January 1898, a riot by Cuban-Spanish loyalists broke out in Havana, destroying newspapers critical of the Spanish Army. The U.S. Consul-General worried about Americans in Havana. In response, the battleship USS Maine was sent to Havana. On February 15, 1898, the Maine was destroyed by an explosion, killing 268 crewmembers. The cause is still unclear, but the incident focused American attention on Cuba. President William McKinley could not stop Congress from declaring war to "liberate" Cuba.

To try and calm the U.S., the Spanish colonial government ended the forced relocation policy and offered to negotiate with the independence fighters. But the rebels rejected the truce, and the offers came too late. Spain asked other European powers for help, but they refused.

On April 11, 1898, McKinley asked Congress to send U.S. troops to Cuba to end the civil war. On April 19, Congress passed resolutions supporting Cuban independence and stating that the U.S. had no intention of annexing Cuba. It demanded Spain's withdrawal and allowed the president to use military force. This was known as the Teller Amendment, which said that Cuba "is, and by right should be, free and independent." It also said U.S. forces would leave once the war was over. War was declared on April 20/21, 1898.

Some historians suggest that the fierce competition between U.S. newspapers, like Joseph Pulitzer's New York World and William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal, played a big role in pushing for war. Others argue that the U.S. wanted to buy Cuba from Spain in 1896, and when that failed, war became an option.

The Spanish–American War in Cuba

The war began when U.S. forces blockaded several Cuban ports. The Americans decided to invade eastern Cuba, where Cubans had strong control and could help. The first U.S. goal was to capture Santiago de Cuba. Between June 22 and 24, 1898, Americans landed east of Santiago and set up a base. Nearby Guantánamo Bay was attacked on June 6 to provide a safe harbor for the U.S. fleet. The Battle of Santiago de Cuba on July 3, 1898, destroyed the Spanish Caribbean fleet.

Major battles between Spanish and American troops took place at Las Guasimas on June 24, and at El Caney and San Juan Hill on July 1. The Americans suffered many casualties. Spanish troops successfully defended Fort Canosa, stabilizing their lines. The Americans and Cubans then began a siege of Santiago, which surrendered on July 16. However, U.S. General Nelson A. Miles did not allow Cuban troops to enter Santiago, claiming he wanted to prevent clashes. Cuban General Calixto García protested this decision.

After losing the Philippines and Puerto Rico, Spain asked for peace on July 17, 1898. On August 12, the U.S. and Spain signed a peace agreement. On December 10, 1898, they signed the formal Treaty of Paris. This treaty recognized continued U.S. military occupation of Cuba. Even though Cubans fought for their freedom, the U.S. prevented them from attending the peace talks or signing the treaty. The treaty also didn't set a time limit for U.S. occupation and excluded the Isle of Pines from Cuba.

U.S. Occupation (1898 - 1902)

After the last Spanish troops left in December 1898, the U.S. temporarily took control of Cuba on January 1, 1899. The first governor was General John R. Brooke. The U.S. did not annex Cuba because of the Teller Amendment, which said the U.S. would not control Cuba permanently.

Political Changes

The U.S. administration was unsure about Cuba's future. They wanted to make sure Cuba stayed friendly to the U.S. Brooke set up a civilian government and appointed U.S. governors for new departments and provinces. Many Spanish colonial officials kept their jobs. The Cuban people were ordered to give up their weapons. Brooke created the Rural Guard and municipal police, ignoring the Mambi Army that fought for independence. Cuba's laws remained based on Spanish rules. Tomás Estrada Palma, a leader of the Cuban Revolutionary Party, dissolved the party after the Paris Treaty, saying its goals were met. The revolutionary assembly was also dissolved.

Economic Changes

Before officially taking over, the U.S. began lowering taxes on American goods entering Cuba, but not on Cuban goods going to the U.S. Government payments had to be made in U.S. dollars. Despite a rule against giving special privileges to American investors, the Cuban economy soon became dominated by American money. American sugar estates grew so fast that by 1905, nearly 10% of Cuba's land belonged to U.S. citizens. By 1902, American companies controlled 80% of Cuba's mineral exports and owned most sugar and cigarette factories.

After the war, there were some legal barriers for foreign businesses in Cuba. However, General Leonard Wood, the governor of Cuba, found a way around these rules. He granted many permits and concessions to American businesses.

Once these legal issues were solved, American investments changed Cuba's economy. Within two years, the Cuba Company built a 350-mile railroad connecting Santiago to central Cuba. This company became the largest foreign investment in Cuba. The improved transportation helped the sugar cane industry spread to eastern Cuba. Many small Cuban sugar producers were in debt after the war, so American companies could buy them cheaply. New large sugar mills, called centrales, could process huge amounts of cane, making large-scale operations very profitable. These large mills were mostly owned by American companies. Cuban cane farmers, who used to own land, became tenants on company land, supplying raw cane to the centrales. By 1902, Americans controlled 40% of Cuba's sugar production.

To strengthen trade, the U.S. lowered its tax on Cuban sugar by 20% in 1903. This made Cuban sugar more competitive in the American market. In return, Cuba gave similar benefits to most goods imported from the U.S. Cuban imports of American goods and exports to the U.S. grew significantly.

Elections and Independence

People soon demanded a Constituent Assembly to write a new constitution. In December 1899, the U.S. War Secretary promised that the occupation was temporary, and elections would be held. General Leonard Wood replaced Brooke to manage this change. New political parties were formed.

The first elections for mayors and other local officials were held on June 16, 1900. Only literate Cubans over 21 with property worth more than $250 could vote. Members of the Liberation Army were exempt. This meant only about 151,000 out of 418,000 men could vote, and women were excluded. The same elections were held again a year later.

Elections for 31 delegates to a Constituent Assembly were held on September 15, 1900, with the same voting rules. In all elections, pro-independence candidates won by a large margin. The Constitution was written from November 1900 to February 1901 and then passed. It created a republican government, guaranteed individual rights, freedom of religion, and separation of church and state.

On March 2, 1901, the U.S. Congress passed the Platt Amendment. This amendment set conditions for the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Cuba and defined future U.S.-Cuba relations. It greatly limited Cuba's independence:

- Cuba could not make treaties with foreign powers that would harm its independence or allow a foreign power to control any part of the island.

- Cuba could not take on foreign debt without being able to pay it back.

- The U.S. could intervene to protect Cuban independence, life, property, and individual liberty.

- The status of the Isle of Pines (now Isla de la Juventud) was not settled and would be decided by treaty.

- Cuba had to provide the U.S. with land for coaling or naval stations.

The U.S. demanded that Cuba approve this amendment as part of its new constitution before gaining independence. After much debate, it was approved. Governor Wood admitted that with the Platt Amendment, Cuba had "little or no independence."

In the presidential elections of December 31, 1901, Tomás Estrada Palma was the only candidate. His opponent, General Bartolomé Masó, withdrew in protest against U.S. favoritism towards Palma. Palma was elected Cuba's first President. The U.S. occupation officially ended when Palma took office on May 20, 1902.

Early 20th Century (1902 - 1959)

In 1902, the United States gave control to a Cuban government. But Cuba's constitution had to include the Platt Amendment, which gave the U.S. the right to intervene militarily. Havana and Varadero quickly became popular tourist spots. Although efforts were made to reduce ethnic tensions, racism against black and mixed-race Cubans remained common.

President Tomás Estrada Palma was elected in 1902. Cuba became independent, but Guantanamo Bay was leased to the U.S. The status of the Isle of Pines was unclear until 1925, when the U.S. recognized it as Cuban territory. Estrada Palma governed well for his four-year term. But when he tried to stay in office longer, a revolt started.

The Second Occupation of Cuba began in September 1906. U.S. President Roosevelt ordered an invasion to stop fighting, protect American businesses, and hold free elections. In 1906, U.S. representative William Howard Taft helped end a revolt. Estrada Palma resigned, and U.S. Governor Charles Magoon took temporary control until 1909. After José Miguel Gómez was elected in November 1908, U.S. troops left in February 1909.

For three decades, Cuba was led by former War of Independence leaders. They served no more than two terms. Under President Gómez, the participation of Afro-Cubans in politics was limited. A black political party was outlawed and violently suppressed in 1912, and American troops re-entered the country to protect sugar plantations. Gómez's successor, Mario Menocal, was a former manager for a sugar company. During his presidency, sugar income greatly increased. Menocal's re-election in 1916 led to a revolt, causing the U.S. to send Marines again to protect American interests.

In World War I, Cuba declared war on Germany in 1917, one day after the U.S. entered the war. Cuba couldn't send troops to Europe but helped protect the West Indies from German U-boat attacks. A draft law was put in place, and 25,000 Cuban troops were raised, but the war ended before they could fight.

Alfredo Zayas was elected president in 1920. When Cuba's financial system collapsed after sugar prices dropped, Zayas got a loan from the U.S. in 1922. Despite its official independence, Cuba was still heavily influenced by the U.S. military and economy.

After World War I

President Gerardo Machado was elected in 1925. He wanted to modernize Cuba and started many large public works projects, like the Central Highway. But at the end of his term, he held onto power. The U.S. decided not to intervene militarily. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, several Cuban groups tried to start uprisings, but they failed.

The Sergeants' Revolt weakened the government. Young revolutionaries, supported by workers and peasants, gained power. From September 1933 to January 1934, a group of activists, students, and soldiers formed a Provisional Revolutionary Government led by Dr. Ramón Grau San Martín. This government promised a "new Cuba" for all people and to end the Platt Amendment.

In the autumn of 1933, the government made many reforms. The Platt Amendment was ended, and political parties from Machado's time were dissolved. The University of Havana gained independence, women got the right to vote, an eight-hour day was set, and a minimum wage was established for sugar cane cutters. A Ministry of Labor was created, and a law said that 50% of workers in certain industries had to be Cuban citizens. The Grau government also aimed for agrarian reform, promising land titles to peasants. This was the first time Cuba was governed by people who didn't negotiate with Spain or the U.S. The Provisional Government lasted until January 1934, when it was overthrown by a group led by Sergeant Fulgencio Batista, with U.S. support.

1940 Constitution and the Batista Era

Batista's Rise

In 1940, Cuba held free and fair elections. Fulgencio Batista was supported by Communist leaders in exchange for legalizing their party and giving them influence in the labor movement. The 1940 Constitution was adopted, but it prevented Batista from running for president again in 1944.

Instead of Batista's chosen successor, Cubans elected Ramón Grau San Martín in 1944. Grau, a doctor, continued Batista's pro-labor policies. His presidency coincided with the end of World War II, and Cuba experienced an economic boom as sugar production and prices rose. He started public works, built schools, increased social security benefits, and encouraged economic growth. However, with prosperity came more corruption and violence. Cuba also gained a reputation as a base for organized crime.

Grau was followed by Carlos Prío Socarrás, who was also democratically elected. His government also faced increasing corruption and violence. Around this time, Fidel Castro became known at the University of Havana. Eduardo Chibás, a nationalist leader, was expected to win the 1952 election on an anti-corruption platform.

Batista, who was not expected to win the 1952 election, seized power in an almost bloodless coup three months before the election. President Prío did nothing to stop it and left the island. Many people initially accepted the coup because of the corruption in the previous governments. However, Batista soon faced strong opposition when he suspended elections and the 1940 constitution, trying to rule by decree. Elections were held in 1954, and Batista was re-elected under disputed conditions. Opposition parties strongly criticized him, using Cuba's free press.

Economic Growth

Despite corruption, Cuba's economy grew under Batista. Wages increased significantly. In 1958, the average industrial salary in Cuba was the world's eighth-highest. Cuba was one of the five most developed countries in Latin America by the end of Batista's rule, with 56% of people living in cities.

In the 1950s, Cuba's gross domestic product (GDP) per person was similar to Italy's and much higher than Japan's. Workers had good rights: an eight-hour day was set in 1933, and Cubans had paid holidays, sick leave, and maternity leave.

Cuba also had high rates of meat, vegetable, cereal, car, telephone, and radio use per person in Latin America. It had the fifth-highest number of televisions per person in the world. Havana was the world's fourth-most-expensive city and had more cinemas than New York. Cuba also had the highest number of telephones in Latin America.

Cuba's health service was very good. By the late 1950s, it had many doctors per person and one of the lowest adult mortality rates in the world. It also had the lowest infant mortality rate in Latin America. Cuba's education spending in the 1950s was the highest in Latin America compared to its GDP. Cuba had the fourth-highest literacy rate in the region, almost 80%.

Problems and Unhappiness

However, educated Cubans compared their country to the United States, not Latin America. They traveled to the U.S., read American newspapers, and watched American TV. Middle-class Cubans became frustrated with the economic gap between Cuba and the U.S. They grew unhappy with Batista's government.

Large differences in income appeared because unionized workers had many privileges. Cuban labor unions limited new machines and even banned firing workers in some factories. These privileges often came "at the cost of the unemployed and the peasants."

Cuba's labor rules eventually slowed down the economy. Investment declined. The World Bank also said that Batista's government raised taxes without thinking about the effects. Unemployment was high, and many university graduates couldn't find jobs. After its fast growth, Cuba's GDP grew by only 1% per year on average between 1950 and 1958.

Political Control and Human Rights

In 1952, Batista, with U.S. support, suspended the 1940 Constitution and took away most political freedoms, including the right to strike. He sided with the wealthiest landowners who owned the largest sugar plantations. The economy slowed, and the gap between rich and poor Cubans grew. Most of the sugar industry was controlled by the U.S., and foreigners owned 70% of the farmland. To stop growing unhappiness, Batista increased media censorship. He also used his secret police to carry out widespread violence and harsh punishments. These actions increased in 1957 as Fidel Castro gained more influence. Many people were killed.

Cuban Revolution (1952 - 1959)

In 1952, Fidel Castro, a young lawyer, tried to legally remove Batista's government, but the courts ignored him. Castro then decided to use armed force. He and his brother Raúl gathered supporters and attacked the Moncada Barracks near Santiago de Cuba on July 26, 1953. The attack failed, and Castro was captured and sentenced to 15 years in prison. However, Batista's government released him in 1955 as part of a general amnesty for political prisoners. Castro and his brother went to Mexico, where they met Ernesto "Che" Guevara. In Mexico, they formed the 26 July Movement to overthrow Batista. In December 1956, Fidel Castro led 82 fighters to Cuba on the yacht Granma. Batista's forces quickly killed or captured most of Castro's men.

Castro escaped into the Sierra Maestra mountains with only about 12 fighters, helped by local opposition groups. Castro and Guevara started a guerrilla campaign against Batista's government. Growing resistance against Batista, including a revolt by the Cuban Navy, led to chaos. Other guerrilla groups also became active in the Escambray Mountains. Castro tried to organize a general strike in 1958 but couldn't get support from Communists or labor unions. Batista's attempts to crush the rebels failed. Castro's forces captured weapons, including a government M4 Sherman tank, which they used in the Battle of Santa Clara.

The United States limited trade with Batista's government and sent an envoy to persuade Batista to leave. As the military situation became impossible, Batista fled on January 1, 1959, and Castro took over. Within months, Castro began to strengthen his power by removing other resistance groups and imprisoning or executing opponents. As the revolution became more radical, thousands of Cubans, especially the wealthy and landowners, fled the island. Over decades, they formed a large exile community in the United States.

Castro's Cuba (1959 - 2006)

Politics

On January 1, 1959, Che Guevara marched his troops into Havana without resistance. Fidel Castro's soldiers marched to the Moncada Army Barracks, where all 5,000 soldiers joined the revolutionary movement. On February 4, 1959, Fidel Castro announced a huge reform plan. This included public works, land reform for nearly 200,000 families, and taking control of various industries.

The new Cuban government soon faced opposition from militant groups and the United States. Fidel Castro quickly removed political opponents from the government. Loyalty to Castro and the revolution became the most important factor for all appointments. Large organizations like labor unions that opposed the revolutionary government were made illegal. By the end of 1960, all opposition newspapers were closed, and all radio and television stations were controlled by the state. Teachers who were involved in counter-revolution were removed. Fidel's brother Raúl Castro became the commander of the Revolutionary Armed Forces. In September 1960, a system of neighborhood watch networks, called Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDR), was created.

In July 1961, the Integrated Revolutionary Organizations (IRO) was formed, combining Castro's 26th of July Movement with other groups. On March 26, 1962, the IRO became the United Party of the Cuban Socialist Revolution (PURSC). This, in turn, became the Communist Party on October 3, 1965, with Castro as its leader. In 1976, a national vote approved a new constitution. This constitution confirmed the Communist Party's central role in governing Cuba. Other smaller parties exist but have little power and cannot campaign against the Communist Party's plans.

Break with the United States

Castro's Dislike of American Influence

The United States recognized Castro's government on January 7, 1959, six days after Batista fled. President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent a new ambassador. The Eisenhower administration believed that Cuba would "remain in the U.S. sphere of influence." If Castro had accepted this, he might have been allowed to stay in power.

However, Castro was part of a group that opposed U.S. influence. He did not forget that the U.S. had supplied weapons to Batista during the revolution. In June 1958, he wrote that Americans would "pay dearly" for their actions and that he would fight a "much longer and bigger war" against them. Castro had no intention of giving in to the United States. He dreamed of a revolution that would change Cuba's society and free it from U.S. control.

Relations Worsen

Just six months after Castro took power, the Eisenhower administration began planning to remove him. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) started arming guerrilla fighters inside Cuba in May 1959.

In March 1960, the French ship La Coubre exploded in Havana Harbor while unloading weapons, killing many people. The CIA blamed the Cuban government.

Relations between the U.S. and Cuba quickly got worse. In July 1960, the Cuban government took control of oil refineries owned by foreign companies because they refused to refine oil from the Soviet Union. The Eisenhower administration encouraged an oil company boycott of Cuba. Cuba responded by taking control of more U.S.-owned properties, including those of the International Telephone and Telegraph Company and the United Fruit Company. In May 1959, Cuba's first agrarian reform law aimed to limit land ownership and give land to small farmers. This law was used to take land owned by foreigners and give it to Cuban citizens.

Official Break

The United States ended diplomatic relations with Cuba on January 3, 1961. It then further limited trade in February 1962. The Organization of American States, pressured by the U.S., suspended Cuba's membership in January 1962. The U.S. government banned all U.S.-Cuban trade on February 7. The Kennedy administration extended this ban in February 1963, forbidding U.S. citizens from traveling to Cuba or doing business with the country.

At first, the embargo didn't stop other countries from trading with Cuba. But the U.S. later pressured other nations and American companies with foreign branches to limit trade with Cuba. The Helms–Burton Act of 1996 made it very difficult for foreign companies doing business with Cuba to also do business in the United States.

Bay of Pigs Invasion

In April 1961, the CIA carried out a plan developed under the Eisenhower administration. This military operation aimed to overthrow Cuba's government and establish a new one friendly to the U.S. The invasion was carried out by a CIA-backed group of over 1,400 Cuban exiles called Brigade 2506. They landed at Playa Girón but were defeated by April 20. President John F. Kennedy took full responsibility. The invasion helped increase popular support for the new Cuban government. Afterward, the Kennedy administration started Operation Mongoose, a secret CIA campaign of sabotage against Cuba, including arming militant groups and plotting to assassinate Castro. This increased Castro's distrust of the U.S. and led to the Cuban Missile Crisis.

The Cuban Missile Crisis

Tensions between the two governments reached their highest point during the October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. The U.S. had many more long-range nuclear weapons than the Soviet Union, and also medium-range missiles in Turkey. Cuba agreed to let the Soviets secretly place medium-range nuclear missiles on its territory. U.S. spy planes discovered the missiles. The U.S. responded by setting up a naval cordon (a type of blockade) to stop Soviet ships from bringing more missiles. At the last moment, the Soviets turned their ships back. They agreed to remove the missiles already in Cuba in exchange for a U.S. promise not to invade Cuba. It was later revealed that another part of the agreement was the removal of U.S. missiles from Turkey. It was also discovered that some Soviet submarines blocked by the U.S. Navy were carrying nuclear missiles, and communication with Moscow was poor, meaning the submarine captains could have decided to fire the missiles.

Military Growth

In 1961, the Communist government showed off Soviet tanks and other weapons in a parade. Cuban officers received military training in the Soviet Union, learning to use advanced Soviet weapons like MIG jet fighters and submarines. For about 30 years, Moscow provided the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces with almost all its equipment, training, and supplies, worth about $1 billion annually. By 1982, Cuba had the best-equipped and largest armed forces per person in Latin America.

Controlling Dissent

Military Units to Aid Production or UMAPs (Unidades Militares para la Ayuda de Producción) were set up in 1965. These were like forced labor camps meant to remove "bourgeois" and "counter-revolutionary" ideas from the Cuban population. The name "UMAP" was removed in 1968, but the camps continued.

By the 1970s, living standards in Cuba were very basic, and many people were unhappy. Castro changed economic policies. In the 1970s, unemployment became a problem again. A law in 1971 made unemployment a crime, and unemployed people could be jailed. One alternative was to fight in Soviet-supported wars in Africa.

Many people who disagreed with the government were held and treated harshly in prisons. Some groups faced severe treatment.

Emigration

The establishment of a socialist system in Cuba led many hundreds of thousands of upper- and middle-class Cubans to flee to the United States and other countries. By 1961, thousands had left for the U.S. On March 22, 1961, an exile council was formed to plan the overthrow of the Communist government.

Between 1959 and 1993, about 1.2 million Cubans left the island for the United States, often in small boats. It's estimated that between 30,000 and 80,000 Cubans died trying to flee during this time. Many also went to Spain if they had dual citizenship. Over decades, some Cuban Jews were allowed to move to Israel. By the time the Soviet Union collapsed, Cubans lived in many different countries, including Spain, Italy, Mexico, and Canada.

On November 6, 1965, Cuba and the U.S. agreed to an airlift for Cubans who wanted to move to the U.S. The first "Freedom Flight" left Cuba on December 1, 1965. By 1971, over 250,000 Cubans had flown to the U.S. In 1980, another 125,000 came to the U.S. during the Mariel boatlift, including some people who caused problems. It was found that the Cuban government used this event to send unwanted people out of Cuba. In 2012, Cuba removed its exit permit requirement, making it easier for citizens to travel abroad.

Involvement in Other Countries' Conflicts

From the start, the Cuban Revolution aimed to spread its ideas and gain allies abroad. Even though Cuba was a developing country, it supported African, Latin American, and Asian countries with military help, health care, and education. These "overseas adventures" sometimes caused disagreements with the Soviet Union.

Cuba openly supported the Sandinista insurgency in Nicaragua, which ended the Somoza dictatorship in 1979. However, Cuba was most active in Africa, supporting 17 liberation movements or leftist governments in countries like Angola, Ethiopia, and Mozambique. Cuba even offered to send troops to Vietnam, but Vietnam declined.

By the late 1970s, Cuba had about 39,000–40,000 military personnel abroad. Most were in Sub-Saharan Africa. Cuba's help in Angola was very important, providing strong support to the Marxist–Leninist MPLA in the Angolan Civil War.

Cuban soldiers in Angola helped defeat South African and Zairian troops. They also defeated other armies and helped the MPLA control most of Angola. In 1978, in Ethiopia, 16,000 Cuban fighters, along with the Ethiopian Army, defeated an invading force from Somalia. South African soldiers were involved in the Angolan Civil War again in 1987–88, and battles were fought between Cuban and South African forces. Cuban-piloted planes attacked South African forces.

Moscow used Cuban troops in Africa and the Middle East because they were well-trained, knew how to use Soviet weapons, were tough, and had a history of successful guerrilla warfare. Most Cuban forces in Africa were black and mixed-race.

An estimated 7,000–11,000 Cubans died in conflicts in Africa. Cuba could not pay for these military activities on its own. After losing Soviet support, Cuba withdrew its troops from Ethiopia (1989), Nicaragua (1990), Angola (1991), and other places.

Angola

Cuba's involvement in the Angolan Civil War began in the 1960s, supporting the MPLA. In 1975, the South African Defence Force (SADF) intervened in Angola. Cuban troops started arriving in Angola in October 1975. On November 4, Cubans stopped a South African column with rocket fire. Castro responded by sending a massive amount of supplies to Angola.

On November 10, an anti-Communist force attacked near Luanda. Cuban and MPLA troops heavily bombarded them, destroying many armored cars. The Cubans then moved forward, using rockets and anti-aircraft guns, killing hundreds. The South Africans could not help and retreated. The Cuba-MPLA victory largely ended the importance of the opposing force. Between December 9 and 12, Cuban and South African troops fought in the "Battle of Bridge 14." The Cubans suffered many casualties. Following these defeats, the number of Cuban troops sent to Angola more than doubled. Cuban forces launched a counter-offensive in January 1976, forcing South Africa to withdraw by the end of March.

In February 1976, Cuban forces fought against irregulars in Cabinda, encircling and cutting off their supplies. Many irregulars were killed or captured.

In 1987–88, South Africa again sent forces to Angola, leading to the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale. The SADF could not defeat the Angolan and Cuban forces.

At its peak, Cuba had up to 50,000 soldiers in Angola. On December 22, 1988, Angola, Cuba, and South Africa signed an agreement in New York. This arranged for the withdrawal of South African and Cuban troops and the independence of Namibia. Cuba's intervention made it a "global player" during the Cold War. Their presence helped the MPLA control large parts of Angola and helped secure Namibia's independence. The withdrawal of Cubans ended 13 years of foreign military presence in Angola. At the same time, Cuba removed its troops from the Republic of the Congo and Ethiopia.

Other Interventions

- Guinea-Bissau: Some Cubans fought against Portugal in Guinea-Bissau from 1966 to 1974, helping with military planning and artillery.

- Algeria: In October 1963, Cuba sent tanks and troops to Oran to help Algeria in a border dispute with Morocco. A truce was signed within the week.

- Congo: In 1964, Cuba supported a rebellion in Congo-Leopoldville (now Democratic Republic of the Congo). In Congo-Brazzaville (now Republic of the Congo), Cubans acted as military advisors and it served as a supply base for the Angola mission.

- Syria: In late 1973, 4,000 Cuban tank troops were in Syria as part of an armored brigade that fought in the Yom Kippur War until May 1974.

- Ethiopia: Fidel Castro supported the dictator Mengistu Haile Mariam. Cuba provided significant military support to Mariam during his conflict with Somalia in the Ogaden War (1977–1978), sending around 24,000 troops to Ethiopia. Cuban artillery crews helped defeat the Somali forces.

Cuba and Soviet Intelligence

As early as September 1959, a KGB agent was seen in Cuba. The East German Stasi trained personnel for Cuba's Interior Ministry. The relationship between the KGB and Cuba's Intelligence Directorate (DI) was complex. The Soviet Union saw Cuba's new government as a good partner in areas where direct Soviet involvement was not popular. Nikolai Leonov, the KGB chief in Mexico City, was one of the first Soviet officials to see Fidel Castro's potential. In 1963, 1,500 DI agents, including Che Guevara, were invited to the USSR for intensive training in intelligence operations.

Recent History (from 1991)

Starting in the mid-1980s, Cuba faced a crisis called the "Special Period". When the Soviet Union, Cuba's main trading partner, broke apart in 1991, Cuba lost a major supporter. Its economy, which relied on only a few products and buyers, was severely affected. Oil supplies were greatly reduced. Over 80% of Cuba's trade was lost, and living conditions worsened. A ""Special Period in Peacetime"" was declared, meaning cuts in transport, electricity, and even food rationing. The U.S. tightened its trade embargo, hoping it would lead to Castro's downfall. But the government opened the country to tourism, working with foreign companies for hotels and other projects. As a result, the use of U.S. dollars was made legal in 1994, and special stores sold goods only in dollars. This created two separate economies, causing social divisions. However, in October 2004, the Cuban government ended this policy. U.S. dollars were no longer legal tender and were exchanged for convertible pesos with a 10% tax.

Severe food shortages and power outages led to a brief period of unrest, including anti-government protests and increased crime. The Cuban Communist Party formed "rapid-action brigades" to confront protesters. In July 1994, 41 Cubans drowned trying to flee the country on a tugboat; the Cuban government was later accused of sinking the vessel.

Thousands of Cubans protested in Havana during the Maleconazo uprising on August 5, 1994. However, security forces quickly broke them up. This was the closest the Cuban opposition came to making a decisive stand.

Continued Isolation and Regional Engagement

Although contacts between Cubans and foreign visitors became legal in 1997, extensive censorship had isolated Cuba. In 1997, a group led by Vladimiro Roca asked the Cuban general assembly for democratic and human rights reforms. Roca and his associates were imprisoned but later released. In 2001, Cuban activists collected thousands of signatures for the Varela Project, asking for a vote on the island's political process. This was supported by former U.S. President Jimmy Carter during his 2002 visit. The petition had enough signatures but was rejected by the Cuban government. Instead, a vote was held that formally declared Castro's socialism would be permanent.

In 2003, Castro cracked down on independent journalists and other people who disagreed with the government in an event known as the "Black Spring". The government imprisoned 75 people, including journalists and human rights activists, claiming they were working for the U.S. government.

Despite being largely isolated from Western countries, Cuba built alliances in its region. After Hugo Chávez became president of Venezuela in 1999, Cuba and Venezuela formed a close relationship based on shared political ideas, trade, and opposition to U.S. influence. Cuba also continued its practice of sending doctors to help poorer countries in Africa and Latin America.

End of Fidel Castro's Presidency

In 2006, Fidel Castro became ill and stepped back from public life. The next year, Raúl Castro became Acting President, taking over from his brother. In a letter on February 18, 2008, Fidel Castro announced his formal resignation as President. In late 2008, Cuba was hit by three major hurricanes, causing over $5 billion in damage and leaving many homeless. In March 2012, the retired Fidel Castro met Pope Benedict XVI during the Pope's visit to Cuba.

Improving Foreign Relations

In July 2012, Cuba received its first American goods shipment in over 50 years, after the U.S. relaxed its embargo for humanitarian aid. In October 2012, Cuba announced it would end its disliked exit permit system, giving citizens more freedom to travel abroad. In February 2013, Raúl Castro said he would retire from government in 2018. In July 2013, Cuba was involved in a diplomatic issue when a North Korean ship illegally carrying Cuban weapons was seized by Panama.

Cuba and Venezuela remained allies after Hugo Chávez's death in March 2013. However, Venezuela's severe economic problems in the mid-2010s reduced its ability to support Cuba. This may have helped improve Cuban-American relations. In December 2014, after a public exchange of political prisoners, U.S. President Barack Obama announced plans to re-establish diplomatic relations with Cuba after over five decades. He said the U.S. would open an embassy in Havana and improve economic ties. In April 2015, the U.S. government removed Cuba from its list of state sponsors of terrorism. The U.S. embassy in Havana officially reopened in August 2015.

Economic Reforms

As of 2015, Cuba remains one of the few officially socialist states in the world. Despite being diplomatically isolated and having economic problems, major currency reforms began in the 2010s. Efforts to allow more domestic private enterprise are now underway. Living standards have improved significantly since the difficult Special Period. GDP per capita (how much money each person makes on average) has risen. Tourism has also become an important source of income for Cuba.

Despite reforms, Cuba still faces ongoing shortages of food and medicines. Electrical and water services are sometimes unreliable. In July 2021, the largest protests since 1994 happened because of these problems and the government's response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

After the Castro Era

Fidel Castro was succeeded by his brother, Raúl Castro, as leader of the Communist party in 2011 and as president in 2008. In 2018, Miguel Díaz-Canel took over from Raúl Castro as president. In April 2021, Miguel Díaz-Canel also succeeded Raúl Castro as the leader of the Communist Party, which is the most powerful position in Cuba. He is the first person to hold both the Cuban presidency and the leadership of the Communist Party without being a member of the Castro family.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Cuba para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Cuba para niños

- History of the Caribbean

- History of Cuban nationality

- History of Latin America

- List of colonial governors of Cuba

- List of Cuba hurricanes

- List of presidents of Cuba

- Politics of Cuba

- Spanish Empire

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

- Timeline of Cuban history

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |