History of the Caribbean facts for kids

The history of the Caribbean shows how important this region was in the battles between European powers starting in the 1400s. Even today, it's still a key area for trade and strategy. In 1492, Christopher Columbus arrived in the Caribbean and claimed it for Spain. The first Spanish settlements were built there the next year. Even though Spain later focused on conquering the Aztec empire and the Inca empire (which had lots of gold), the Caribbean remained very important for Spain's plans.

From the 1620s and 1630s, other European countries like France, England, and the Netherlands started building their own colonies and trading posts. They settled on islands that Spain hadn't fully controlled. These colonies spread from the Bahamas to Tobago. Also, during this time, French and English buccaneers (a type of pirate) settled on Tortuga, parts of Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic), and later in Jamaica.

After the Spanish American War in 1898, Cuba and Puerto Rico were no longer part of the Spanish Empire. In the 1900s, the Caribbean was important again during World War II. It also played a role in the wave of countries gaining independence after the war, and during the tensions between Communist Cuba and the United States. Many islands have become independent countries, while others still have ties with major powers like the U.S. The early ways the Caribbean connected to the world economy still affect the region today.

Contents

Life Before Europeans Arrived

When Europeans first arrived in 1492, many different native groups lived on the Caribbean islands. Scientists have studied how these populations started and changed over time. Thousands of years ago, the northern part of South America was home to groups who hunted small animals, fished, and gathered food. They moved around a lot to find different plants and animals, but sometimes stayed in one place for a while.

Archaeological finds suggest that Trinidad was the first Caribbean island settled, as early as 9000 to 8000 BCE. These first settlers probably arrived when Trinidad was still connected to South America by land bridges. Around 7000 to 6000 BCE, Trinidad became an island because sea levels rose a lot, possibly due to climate change. This means Trinidad was the only Caribbean island that could be reached by land from South America. The oldest major settlement sites found in Trinidad are shell piles called middens at Banwari Trace and St. John. These date back to 6000 to 5100 BCE. These shell piles show that people ate a lot of shellfish and used stone and bone tools.

Scholars have tried to divide Caribbean history before Europeans into different "ages." This is a tricky and debated topic. In the 1970s, archaeologist Irving Rouse suggested three "ages" based on archaeological finds: the Lithic, Archaic, and Ceramic Ages. These terms are still used today, but their exact meanings are often discussed.

- The Lithic Age is seen as the first period of human development in the Americas, when people first started shaping stone tools.

- The Archaic Age often describes groups who specialized in hunting, fishing, gathering, and managing wild food plants.

- Ceramic Age communities made pottery and practiced small-scale farming.

Except for Trinidad, the first Caribbean islands were settled between 3500 and 3000 BCE, during the Archaic Age. Sites from this time have been found in Barbados, Cuba, Curaçao, and St. Martin. Soon after, Hispaniola and Puerto Rico were also settled.

Between 800 and 200 BCE, a new group of people, called the Saladoid, spread through the Caribbean islands. They are known for their unique pottery, often painted with white-on-red designs. People used to think the Saladoid groups brought pottery and farming to the Caribbean, starting the Ceramic Age. However, recent studies show that some older Caribbean groups already had crops and pottery before the Saladoid arrived. While many islands were settled during the Archaic and Ceramic Ages, some were visited much later. Jamaica has no known settlements until around 600 CE, and the Cayman Islands show no signs of settlement before Europeans arrived.

After Trinidad was settled, it was thought that Saladoid groups moved from island to island all the way to Puerto Rico. But new research suggests a different idea: that the northern islands were settled directly from South America, and then people moved south into the Lesser Antilles. This idea is supported by carbon dating and computer models of sea travel. One reason people might have moved from the mainland to the northern islands was to find good quality materials like flint. Flinty Bay on Antigua was a famous source of high-quality flint, and flint from Antigua has been found on many other Caribbean islands.

From 650 to 800 CE, big cultural and social changes happened in the Caribbean. The Saladoid way of life changed quickly. This period also saw a shift in climate, with long droughts and more hurricanes. The Caribbean population generally grew, and communities changed from small, scattered villages to larger groups of settlements. Farming increased. Studies of cultural items also show that islands became more connected during this time.

After 800 CE, societies started to become more organized, with leaders gaining more power. After about 1200 CE, many Caribbean settlements became part of the larger societies forming in the Greater Antilles. This changed how local communities developed and led to bigger social and political changes.

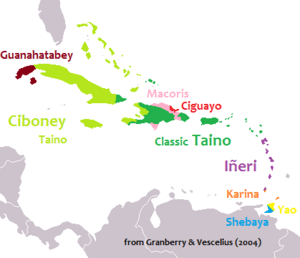

When Europeans arrived, three main groups of native peoples lived on the islands:

- The Taíno (also called Arawak) lived in the Greater Antilles, the Bahamas, and the Leeward Islands.

- The Kalinago and Galibi lived in the Windward Islands.

- The Ciboney lived in western Cuba.

Scholars divide Taínos into Classic Taínos (Hispaniola and Puerto Rico), Western Taínos (Cuba, Jamaica, Bahamas), and Eastern Taínos (Leeward Islands). Trinidad had both Carib-speaking and Arawak-speaking groups.

DNA studies have changed some old ideas about native Caribbean history. In 2003, a scientist named Juan Martínez Cruzado found that 61% of Puerto Ricans have Native American DNA, 27% have African DNA, and 12% have European DNA. According to National Geographic, "Most of the Caribbean’s original inhabitants may have been wiped out by South American newcomers a thousand years before the Spanish invasion that began in 1492. Also, the native populations of islands like Puerto Rico and Hispaniola were likely much smaller when the Spanish arrived than previously thought."

Early European Control

Soon after Christopher Columbus's trips to the Americas, both Portugal and Spain started claiming lands in Central and South America. These colonies brought back gold. Other European powers, especially England, the Netherlands, and France, wanted to set up their own profitable colonies. This competition between empires made the Caribbean a battleground during European wars for centuries. In the early 1800s, most of Spanish America broke away from Spain. However, Cuba and Puerto Rico stayed under Spanish rule until the Spanish–American War in 1898.

Spain's Early Settlements

Spain's contact with new lands and peoples began with Columbus's first voyage in 1492. Permanent Spanish settlements started in 1493. The first 25 years of Spanish settlement in the Caribbean set patterns that would be repeated across the Americas. After Spain conquered the Aztec Empire and the Inca Empire, which had many native people and rich gold and silver deposits, the Caribbean became less of a main focus for Spain. But the ways Spain organized its government, society, and culture in the Caribbean lasted a long time.

Spanish contact with native peoples in the Caribbean had terrible effects. Many natives died from diseases and overwork. This led Spanish settlers to look for native labor on other islands, forcing natives into slavery and moving them to Spanish settlements. The Spanish crown tried to protect the native population and stop settlers from mistreating them by creating new laws.

During his first trip in 1492, Columbus met the Lucayans in the Bahamas and the Taíno in Cuba and northern Hispaniola. Starting with his second trip in 1493, Spaniards came to live permanently in the region. Spaniards saw gold ornaments on natives, which made them eager to find wealth. Spain claimed the entire Caribbean and signed the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) with Portugal, dividing the world between them. However, Spaniards only settled the larger islands: Hispaniola (1493), where they founded Santo Domingo; Puerto Rico (1508); Jamaica (1509); Cuba (1511); and Trinidad (1530). They also settled the small 'pearl islands' of Cubagua and Margarita Island off Venezuela, which had valuable pearl beds.

Spaniards settled permanently in the Caribbean, hoping to live lives similar to or better than what they had in Spain. They wanted to build Spanish-style cities with lasting residents. They expected to use forced labor from the native population to make their settlements profitable. Spaniards made natives grow food for them, which was hard on farming that didn't usually produce much extra. Spaniards felt it was their right to force natives to work for them, often far from their homes. This labor was given to individual Spanish settlers through grants called encomiendas. The holders of these grants, encomenderos, made natives search for and mine gold. The most famous account of these abuses was by a friar named Bartolomé de las Casas, who convinced the Spanish crown to create laws to stop the mistreatment and the rapid decline of native populations. To add to and then replace the shrinking native workforce, the Spanish brought enslaved Africans to the Caribbean to work on plantations growing cane sugar, a very valuable product.

Spaniards continued exploring islands and the lands around the Caribbean Sea, looking for more native populations and wealth. The expedition of Hernán Cortés from Cuba led to the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire in 1521. This shifted Spain's main focus to Mexico.

Other European Powers Arrive

Even though the Caribbean was still important for Spain, other European powers started to arrive after Spain focused on Mexico and Peru. These areas had many native people who could be forced to work and rich silver mines. The Dutch, French, and English took over islands that Spain claimed but didn't fully control. For European powers without colonies in the Americas, these islands offered chances to grow sugar on plantations, just like Spain did, using enslaved African workers. The islands also served as bases for trade and piracy. Piracy was common in the Caribbean during the colonial era, especially from 1640 to 1680. The term "buccaneer" often describes a pirate in this region.

- Francis Drake was an English privateer (a legal pirate) who attacked many Spanish settlements. He famously captured the Spanish Silver Train at Nombre de Dios in 1573.

- British colonization of Bermuda began in 1612. British West Indian colonization started with Saint Kitts in 1623 and Barbados in 1627. St. Kitts was used as a base to colonize nearby islands like Nevis (1628), Antigua (1632), Montserrat (1632), Anguilla (1650), and Tortola (1672).

- French colonization also began on St. Kitts, with the British and French sharing the island in 1625. It was used as a base to colonize larger islands like Guadeloupe (1635) and Martinique (1635), St. Martin (1648), St Barts (1648), and St Croix (1650). France lost St. Kitts to Britain in 1713. From Martinique, the French colonized St. Lucia (1643), Grenada (1649), Dominica (1715), and St. Vincent (1719).

- English admiral William Penn captured Jamaica in 1655, and it remained under British rule for over 300 years.

- In 1625, French buccaneers settled on Tortuga, north of Hispaniola. Spain tried many times but could never permanently destroy this settlement. Tortuga was officially established in 1659 under King Louis XIV. In 1670, Cap François (now Cap-Haïtien) was built on the mainland of Hispaniola. By the Treaty of Ryswick in 1697, Spain officially gave the western third of Hispaniola to France.

- The Dutch took over Saba, Saint Martin, Sint Eustatius, Curaçao, Bonaire, Aruba, Tobago, St. Croix, Tortola, Anegada, Virgin Gorda, and Anguilla in the 1600s. These were called the Dutch West Indies.

- Denmark-Norway ruled parts, then all, of the present U.S. Virgin Islands from 1672. Denmark sold these islands to the United States in 1917.

Early French Attacks

French pirate attacks started in the early 1520s, as soon as France declared war on Spain in 1521. At this time, huge treasures from Mexico began to cross the Atlantic to Spain. French King Francis I challenged Spain's claim to the Americas and its wealth. He famously asked to see "the clause in Adam’s will which excluded me from my share when the world was being divided." Giovanni da Verrazzano (also known as Jean Florin) led the first recorded French pirate attack against Spanish ships carrying treasures from the New World. In 1523, off the coast of Portugal, his ships captured two Spanish vessels loaded with gold, silver, pearls, and 25,000 pounds of sugar, which was a very valuable item then.

The first recorded attack in the Caribbean happened in 1528. A French pirate ship appeared off Santo Domingo and its crew robbed the village of San Germán on the western coast of Puerto Rico. In the mid-1530s, pirates, some Catholic but most Protestant, began regularly attacking Spanish ships and raiding Caribbean ports and towns. The most desired targets were Santo Domingo, Havana, Santiago, and San Germán. Pirate raids on ports in Cuba and elsewhere often followed a "ransom" model. The attackers would seize villages and cities, kidnap local residents, and demand money for their release. If there were no hostages, pirates demanded ransoms to prevent towns from being destroyed. Whether ransoms were paid or not, pirates looted and often committed violence, damaged churches, and left behind burning reminders of their attacks.

In 1536, France and Spain went to war again, and French pirates launched many attacks on Spanish Caribbean settlements and ships. The next year, a pirate ship appeared in Havana and demanded a ransom. Spanish warships arrived and scared off the ship, but it soon returned to demand another ransom. Santiago was also attacked that year, and both cities were raided again in 1538. The waters off Cuba's northwest became very attractive to pirates because merchant ships returning to Spain had to pass through the narrow strait between Key West and Havana. In 1537–1538, pirates captured and robbed nine Spanish ships. Even when France and Spain were at peace until 1542, pirate activity continued. When war started again, it affected the Caribbean once more. A particularly brutal French pirate attack happened in Havana in 1543, killing 200 Spanish settlers. In total, between 1535 and 1563, French pirates carried out about sixty attacks against Spanish settlements and captured over seventeen Spanish ships in the region.

European Rivalries and Their Impact

While France and Spain fought in Europe and the Caribbean, England sided with Spain, mostly because of family alliances. Spain's relationship with England worsened when the Protestant Elizabeth I became Queen in 1558. She openly supported the Dutch rebellion against Spain and helped Protestant forces in France. After decades of growing tensions, Anglo-Spanish fighting broke out in 1585. Queen Elizabeth sent over 7,000 troops to the Netherlands and gave many licenses for privateers to attack Spain's Caribbean possessions and ships. Tensions grew even more in 1587 when Elizabeth I ordered the execution of Mary Queen of Scots and ordered an attack on the Spanish Armada in Cadiz. In response, Spain organized the famous naval attack that ended badly for Spain with the destruction of the "invincible" Armada in 1588. Spain rebuilt its navy, largely with ships built in Havana, and continued to fight England until Elizabeth's death in 1603. However, Spain had been severely weakened, ending its position as Europe's most powerful nation and undisputed master of the Americas.

After the French-Spanish peace treaty of 1559, official French pirate activities decreased, but Protestant pirate attacks continued. In one case, this led to a temporary Protestant settlement on the Isle of Pines, off Cuba. English piracy increased during the rule of Charles I, King of England (1625–1649), and became more aggressive as Anglo-Spanish relations worsened during the Thirty Years' War. Although Spain had been dealing with the Dutch rebellion since the 1560s, the Dutch arrived late to the Caribbean. They appeared in the region only after the mid-1590s, when the Dutch Republic was no longer on the defensive against Spain. Dutch privateering became more widespread and violent starting in the 1620s.

English attacks in the Spanish-claimed Caribbean grew during Queen Elizabeth's rule. These actions first appeared as large-scale smuggling trips led by pirate-smugglers like John Hawkins, John Oxenham, and Francis Drake. One of their main goals was smuggling enslaved Africans into Spain's Caribbean colonies in exchange for tropical products. The first English merchant piracy happened in 1562–63, when Hawkins’ men raided a Portuguese ship off Sierra Leone, captured 300 enslaved people, and smuggled them into Santo Domingo for sugar, hides, and valuable woods. Hawkins and other slave traders found ways to pack as many enslaved Africans as possible onto a ship, forcing them to lie on their sides, spooned against each other. For example, Hawkins's ship Jesus of Lübeck carried hundreds of enslaved Africans. In 1567 and 1568, Hawkins led two more smuggling trips. The last one ended badly; he lost almost all his ships and three-fourths of his men were killed by Spanish soldiers at San Juan de Ulúa, off Veracruz. Hawkins and Drake barely escaped, but Oxenham was captured, found guilty of heresy by the Mexican Inquisition, and burned alive.

Many battles of the Anglo-Spanish war were fought in the Caribbean, not by regular English forces, but by privateers licensed by Queen Elizabeth to attack Spanish ships and ports. These were former pirates who now had a more respected status. During those years, over seventy-five documented English privateering trips targeted Spanish possessions and ships. Drake terrorized Spanish vessels and ports. In early 1586, his forces captured Santo Domingo, holding it for about a month. Before leaving, they robbed and destroyed the city, taking a huge amount of loot. Drake's men also destroyed religious images and decorations in Catholic churches.

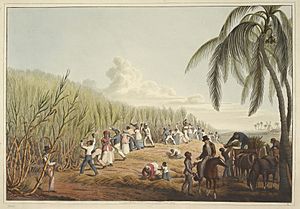

The Enslavement of Africans

Growing crops in the Caribbean needed a huge number of workers. Europeans met this need by forcing millions of enslaved Africans to move to the Americas. The Atlantic slave trade brought these enslaved people to Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, English, and French colonies. Enslaved Africans were brought to the Caribbean from the early 1500s until the late 1800s, with most arriving between 1701 and 1810.

Here's a table showing how many enslaved people were brought to some Caribbean colonies:

| Caribbean colonizer | 1492–1700 | 1701–1810 | 1811–1870 | Total number of slaves imported |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Caribbean | 263,700 | 1,401,300 | — | 1,665,000 |

| Dutch Caribbean | 40,000 | 460,000 | — | 500,000 |

| French Caribbean | 155,800 | 1,348,400 | 96,000 | 1,600,200 |

People who wanted to end slavery, called abolitionists, spoke out against the slave trade throughout the 1800s. Importing enslaved people was often outlawed years before slavery itself ended. It took until the late 1800s for many enslaved people in the Caribbean to become legally free. The trade in enslaved people was stopped in the British Empire in 1807. However, enslaved people in the British Empire remained enslaved until the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833. When this Act took effect in 1834, about 700,000 enslaved people in the British West Indies became free immediately. Others were freed a few years later after a period of apprenticeship. Slavery was abolished in the Dutch Empire in 1814. Spain abolished slavery in its empire in 1811, except for Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Santo Domingo. Spain ended the slave trade to these colonies in 1817, after Britain paid them £400,000. Slavery itself was not abolished in Cuba until 1886. France abolished slavery in its colonies in 1848.

Family Life and Sales

Plantation owners often tried to deny that enslaved people had loving bonds or lasting relationships. This made it easier to justify separating families by selling them. From the very beginning of slavery, sales and separations severely disrupted the home lives of enslaved individuals. Enslaved spouses could be sold separately. They lived as single people or with their mothers or extended families, but still considered themselves 'married'. Selling plantations with "stock" (including enslaved people) to pay debts, which became more common later in slavery, was criticized for separating enslaved spouses.

Some argued for families to be sold together or kept as close as possible. Laws were passed later in slavery to try and prevent families from being broken up by sale, but these laws were often ignored. Enslaved people often reacted strongly to being separated from their loved ones, feeling "sorrow and despair." Sometimes, this distress even led to death. Some argued against separation because it caused enslaved people to feel "despair," "utter despondency," or even "put a period to their lives." Separated enslaved people often used their free time to travel long distances to reunite for a night. Sometimes, runaway enslaved people were married couples. However, the sale of enslaved people and the breakup of families decreased as sugar plantations became less profitable.

Colonial Laws About Slavery

European plantations needed laws to control the plantation system and the many enslaved people brought to work there. This legal control was harshest for enslaved people in colonies where they outnumbered their European masters and where rebellions were common, such as Jamaica.

Each European colony in the Caribbean had to create laws about slavery. British West Indian colonies could make their own laws through local governments, with the approval of the colony's governor. In contrast, French, Danish, Dutch, and Spanish colonies were strictly controlled by their home countries, including how they enforced slave codes. The French regulated enslaved people under the Code Noir (Black Code), which was used in all French colonies and was based on early French slavery practices in the Caribbean.

As historian Jan Rogozinski noted, "All [Caribbean] islands sought to protect the planter and not the slave." Slave codes in the British West Indies often did not recognize marriage for enslaved people, family rights, education for enslaved people, or the right to religious practices or holidays. The Code Noir did recognize slave marriages, but only with the master's permission. Like Spanish colonial law, it also legally recognized marriages between European men and black or Creole women. These laws were also more generous than British ones in allowing enslaved people to gain their freedom.

Slave Rebellions

The plantation system and the slave trade that supported it led to regular resistance from enslaved people on many Caribbean islands throughout the colonial era. Resistance included escaping from plantations and seeking safety in areas without European settlements. Communities of escaped enslaved people, known as Maroons, gathered in heavily forested and mountainous areas of the Greater Antilles and some of the Lesser Antilles. As plantations and European settlements spread, many Maroon communities ended. However, they survived on Saint Vincent and Dominica, and in the more remote mountains of Jamaica, Hispaniola, Guadeloupe, and Cuba.

Violent resistance broke out regularly on the larger Caribbean islands. Many more plans for rebellions were discovered and stopped by Europeans before they could happen. But actual violent uprisings, involving dozens to thousands of enslaved people, were common. Jamaica and Cuba especially had many slave uprisings. These uprisings were brutally crushed by European forces.

Caribbean Slave Uprisings (1522–1844)

Here are some slave rebellions that led to actual violent uprisings:

| Caribbean island | Year of slave uprising |

|---|---|

| Antigua | 1701, 1831 |

| Bahamas | 1830, 1832–34 |

| Barbados | 1816 |

| Cuba | 1713, 1729, 1805, 1809, 1825, 1826, 1830–31, 1833, 1837, 1840, 1841, 1843 |

| Curaçao | 1795 |

| Dominica | 1785–90, 1791, 1795, 1802, 1809-14 |

| Grenada | 1765, 1795 |

| Guadeloupe | 1656, 1737, 1789, 1802 |

| Jamaica | 1673, 1678, 1685, 1690, 1730–40, 1760, 1765, 1766, 1791–92, 1795–96, 1808, 1822–24, 1831–32 |

| Marie Galante | 1789 |

| Martinique | 1752, 1789–92, 1822, 1833 |

| Montserrat | 1776 |

| Puerto Rico | 1527 |

| Saint Domingue | 1791 |

| Saint John | 1733-34 |

| Saint Kitts | 1639 |

| Saint Lucia | 1795-96 |

| Saint Vincent | 1769–73, 1795–96 |

| Santo Domingo | 1522 |

| Tobago | 1770, 1771, 1774, 1807 |

| Tortola | 1790, 1823, 1830 |

| Trinidad | 1837 |

How Colonialism Changed the Caribbean

Economic Control and Dependency

The process of taking wealth from the Caribbean started with the Spanish colonists in the 1490s. They forced native peoples to mine for gold. Gold wasn't the long-term main driver of the Caribbean economy. Instead, it was the growing of sugarcane. Christopher Columbus noticed that the islands were perfect for growing sugarcane, which was a very valuable export. The history of Caribbean farming for export is directly linked to European colonialism. Spaniards copied the idea of sugar plantations from other Atlantic islands, using forced labor.

Before the 1700s, sugar was a luxury in Europe. But with more production and lower prices, it became very popular in the 1700s and a necessity in the 1800s. This change in taste and demand for sugar caused big economic and social shifts. Caribbean islands, with lots of sunshine, rain, and no long frosts, were ideal for growing sugarcane and building sugar factories. However, the native population sharply declined during early Spanish colonization, leading to a lack of workers. Spaniards needed a large and strong workforce for sugar farming, which led to the large-scale forced migration of enslaved Africans.

The success of Spanish Caribbean sugar plantations became a model for other European powers. The Portuguese colony of Brazil also developed large sugar plantations. The high demand for sugar in Europe attracted other European powers to claim Caribbean islands that Spain claimed but didn't fully control. In the 1600s, the Dutch, English, and French took Caribbean islands and started plantation farming. By the mid-1700s, sugar was Britain's largest import, making the Caribbean islands even more important as colonies. The islands also became bases for European trade that bypassed Spain's rules on its trade monopoly.

After slavery was abolished in the 1800s across the Atlantic World, many freed Africans left their former masters. This caused economic problems for the owners of Caribbean sugarcane plantations. The hard work in hot, humid farms needed strong, low-paid workers. Plantation owners looked for cheap labor. They first found it in China and then in India. The plantation owners then created a new legal system of forced labor, which was very similar to slavery. These were indentured laborers, technically not enslaved, but their working conditions were very harsh. Migrants from India began to replace Africans who had been brought as slaves. The first ships carrying indentured laborers for sugarcane plantations left India in 1836. Over the next 70 years, many more ships brought indentured laborers to the Caribbean as cheap labor for difficult work. Millions of enslaved and indentured laborers were brought to the Caribbean, as in other European colonies worldwide.

Farming for export controlled the island economies, with few cities and no industries. Farm workers had no other jobs in cities. Their wages were extremely low with no chance of growing, because producers wanted to keep labor costs low and their profits high. Profits from Caribbean farming were not used for industrial development or to improve conditions for farm workers. As industrialized nations looked for cheap food for their factory workers, Caribbean islands continued to produce sugarcane. Sugarcane was no longer a high-value item only for the rich; Caribbean sugar was cheap enough for factory workers to consider it a basic part of their diet. It would be very hard for Caribbean producers to escape this economic relationship with the developed world that started during the colonial era. Caribbean nations became among the world's poorest.

Wars Affecting the Caribbean

The Caribbean region experienced violence and war throughout much of its colonial history. However, these wars often started in Europe, with only smaller battles fought in the Caribbean.

- The Eighty Years' War was fought between the Netherlands and Spain.

- The First, Second, and Third Anglo-Dutch Wars were battles for control.

- The Nine Years' War involved many European powers.

- The War of Spanish Succession (European name) or Queen Anne's War (American name) led to a generation of famous pirates.

- The War of Jenkins' Ear (American name) or The War of Austrian Succession (European name) involved Spain and Britain fighting over trade rights. Britain invaded Spanish Florida and attacked Cartagena de Indias in present-day Colombia.

- The Seven Years' War (European name) or the French and Indian War (American name) was the first "world war" between France, its ally Spain, and Britain. France lost and was willing to give up all of Canada to keep a few very profitable sugar-growing islands in the Caribbean. Britain captured Havana near the end and traded that single city for all of Florida in the Treaty of Paris in 1763. France also gave Grenada, Dominica, and Saint Vincent (island) to Britain.

- The American Revolution saw large British and French navies fighting in the Caribbean again. American independence was secured by French naval victories in the Caribbean. However, all British islands captured by the French were returned to Britain at the end of the war.

- The French Revolutionary War led to the creation of the newly independent Republic of Haiti. Also, in the Treaty of Amiens in 1802, Spain gave Trinidad to Britain.

- After the Napoleonic War ended in 1814, France gave Saint Lucia to Britain.

- The Spanish–American War (1898) ended Spanish control of Cuba (which soon became independent) and Puerto Rico (which became a U.S. colony). This war marked the beginning of U.S. influence in the islands.

Piracy in the Caribbean was often used by European empires to fight unofficial wars against each other. Gold stolen from Spanish ships and brought to other European nations greatly increased European interest in colonizing the region.

Gaining Independence

Haiti, formerly the French colony of Saint-Domingue on Hispaniola, was the first Caribbean nation to gain independence from European powers in 1804. This happened after 13 years of war, which began as a slave uprising in 1791 and quickly became the Haitian Revolution led by Toussaint Louverture. Black Haitian revolutionaries overthrew the French colonial government. Haiti became the world's first and oldest black republic, and the second-oldest republic in the Western Hemisphere after the United States. This is also notable as the only successful slave uprising in history. The remaining two-thirds of Hispaniola were conquered by Haitian forces in 1821. In 1844, the newly formed Dominican Republic declared its independence from Haiti.

The nations bordering the Caribbean in Central America gained independence with Mexican independence from Spain in 1821. This led to the First Mexican Empire, which included what are now Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. The nations bordering the Caribbean in South America also gained independence from Spain in 1821, forming Gran Colombia, which included the modern states of Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, and Panama.

The islands of Cuba and Puerto Rico remained Spanish colonies until the Spanish–American War in 1898. They were very important to the Spanish Empire, which was much smaller by then. Spain also lost the Philippine Islands to the U.S. in this war. A long civil conflict in Cuba, known as the Ten Years' War, was influenced by the U.S. The treaty ending the war, signed between the U.S. and Spain, did not include Cuban independence fighters. Cuba became independent in 1902 but came under U.S. supervision and economic control. The 1959 Cuban Revolution ended this economic dependency when Cuba allied with the Soviet Union. Puerto Rico became an unincorporated territory of the United States, being the last of the Greater Antilles under Spanish colonial control. Today, there are people who advocate for Puerto Rican independence.

Between 1958 and 1962, most of the British-controlled Caribbean islands joined together as the new West Indies Federation. This was an attempt to create a single independent state, but it failed. The following former British Caribbean island colonies then gained independence on their own: Jamaica (1962), Trinidad and Tobago (1962), Barbados (1966), Bahamas (1973), Grenada (1974), Dominica (1978), St. Lucia (1979), St. Vincent (1979), Antigua and Barbuda (1981), and St. Kitts and Nevis (1983).

In addition, British Honduras in Central America became independent as Belize (1981). British Guiana in South America became independent as Guyana (1966). Dutch Guiana, also in South America, became independent as Suriname (1975).

Islands Still Under Colonial Rule

Not all Caribbean islands have become independent. As of the early 2000s, several islands still have government ties with European countries or with the United States.

French overseas departments and territories include several Caribbean islands. Guadeloupe and Martinique are French overseas regions, a status they have had since 1946. Their citizens are considered full French citizens with the same legal rights. In 2003, the people of St. Martin and St. Barthélemy voted to separate from Guadeloupe to form their own overseas communities of France. After a law was passed in the French Parliament, their new status began on February 22, 2007.

Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands are officially territories of the United States. They are sometimes called "protectorates" of the United States. They govern themselves but are subject to the U.S. Congress.

British overseas territories in the Caribbean include: Anguilla, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Montserrat, and Turks and Caicos.

Aruba, Curaçao, and Sint Maarten are now separate countries within the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Along with the Netherlands, they form the four countries of the Kingdom. Citizens of these islands have full Dutch citizenship.

The United States and the Caribbean

In 1823, President James Monroe's speech included a major change to U.S. foreign policy, which became known as the Monroe Doctrine. A key part of this policy, called the Roosevelt Corollary, gave the United States the right to step in if any nation in the Western Hemisphere was seen as causing "chronic wrongdoing." This new expansionism, combined with the colonial nations losing power, allowed the United States to become a major influence in the region. In the early 1900s, this influence grew through involvement in The Banana Wars. Areas not controlled by Britain or France became known in Europe as "America's tropical empire."

Victory in the Spanish–American War and the signing of the Platt amendment in 1901 gave the United States the right to interfere in Cuba's political and economic affairs, even with military force if needed. After the Cuban revolution of 1959, relations quickly worsened. This led to the Bay of Pigs Invasion, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and repeated U.S. attempts to destabilize the island. The U.S. invaded and occupied Hispaniola (present-day Dominican Republic and Haiti) for 19 years (1915–34). Afterward, it controlled Haiti's economy through aid and loan repayments. The U.S. invaded Haiti again in 1994 to remove a military government and bring back elected President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. In 2004, Aristide was overthrown in a coup, and flown out of the country by the U.S. Aristide later accused the U.S. of kidnapping him.

In 1965, 23,000 U.S. troops were sent to the Dominican Republic to intervene in the Dominican Civil War. The goal was to end the war and prevent supporters of the removed left-wing president Juan Bosch from taking over. This was the first U.S. military intervention in Latin America in over 30 years. President Lyndon Johnson ordered the invasion to stop what he called a "Communist threat." However, the mission seemed unclear and was criticized across the hemisphere as a return to "gunboat diplomacy" (using military power to get what you want). On October 25, 1983, the United States invaded Grenada to remove left-wing leader Hudson Austin, who had taken power nine days earlier. Austin had ordered the execution of Maurice Bishop three days before the invasion. The United States still has a naval military base in Cuba at Guantanamo Bay. This base is part of a command responsible for Latin America and the Caribbean, with its headquarters in Miami, Florida.

The United States' influence goes beyond military actions. Economically, the U.S. is the main market for Caribbean goods. This is a more recent trend. After World War II, as colonial powers started to leave the region, the U.S. began to increase its influence. This pattern is seen in economic programs like the Caribbean Basin Initiative (CBI), which aimed to strengthen alliances with the region due to a perceived threat from the Soviet Union. The CBI shows that the Caribbean Basin became a strategically important area for the U.S.

This relationship continues into the 21st century, as shown by the Caribbean Basin Trade Partnership Act. The Caribbean Basin is also important for trade routes. It's estimated that nearly half of U.S. foreign cargo and oil imports come through Caribbean waterways. During wartime, these numbers would likely increase. It's also important to note that the U.S. is strategically important to the Caribbean. Caribbean foreign policy aims to increase its participation in the global free market economy. Because of this, Caribbean states do not want to be cut off from their main market in the United States. They also don't want to be left out of larger trade agreements that could greatly change trade and production in the Caribbean. So, the U.S. has played a big role in shaping the Caribbean's place in this market. Building trade relationships with the U.S. has always been a key goal for economic security in independent Caribbean states.

Economic Changes in the 1900s

Sugar, the main crop of the Caribbean economy, has slowly declined since the early 1900s. However, it is still a major crop in the region. Caribbean sugar production became relatively expensive compared to other parts of the world that developed their own sugar industries. This made it hard for Caribbean sugar products to compete. So, Caribbean islands had to find new economic activities.

Tourism Grows

By the early 1900s, the Caribbean islands became more politically stable. Large-scale violence was no longer a threat after slavery ended. The British-controlled islands especially benefited from money invested in their infrastructure. By the start of World War I, all British-controlled islands had their own police force, fire department, doctors, and at least one hospital. Sewage systems and public water supplies were built, and death rates on the islands dropped sharply. Literacy also increased a lot during this time, as schools were set up for students descended from enslaved Africans. Public libraries were established in large towns and capital cities.

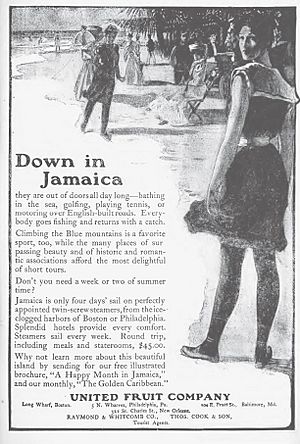

These improvements made the islands much more attractive for visitors. Tourists started to visit the Caribbean in larger numbers by the early 1900s, though some tourism existed as early as the 1880s. The U.S.-owned United Fruit Company ran a fleet of "banana boats" in the region that also carried tourists. The United Fruit Company also built hotels for tourists. However, it soon became clear that this industry was like a new form of colonialism. The hotels were fully staffed by Americans, from chefs to waitresses, and owned by Americans. This meant local people saw little economic benefit. The company also practiced racial discrimination on its ships. Black passengers were given worse cabins, sometimes denied bookings, and expected to eat meals early before white passengers. The most popular early destinations were Jamaica and the Bahamas. The Bahamas remains the most popular tourist destination in the Caribbean today.

After gaining independence, especially when old agricultural trade ties with Europe ended, there was a boom in the tourism industry in the 1980s and beyond. Large luxury hotels and resorts have been built by foreign investors on many islands. Cruise ships also visit the Caribbean regularly.

Some islands have gone against this trend, like Cuba and Haiti, whose governments chose not to focus on foreign tourism. However, Cuba has recently started to develop its tourism industry. Other islands without sandy beaches, like Dominica, missed out on the 1900s tourism boom. But they have recently started to develop eco-tourism, which adds variety to the Caribbean tourism industry.

Financial Services

The development of offshore banking services began in the 1920s. The Caribbean islands are close to the United States, making them an attractive location for branches of foreign banks. Clients from the United States use offshore banking services to avoid U.S. taxes. The Bahamas was the first to enter the financial services industry and continues to be a leader in the region. The Cayman Islands, British Virgin Islands, and Netherlands Antilles have also developed strong financial services industries. In recent years, lower interest rates and higher costs related to fighting money laundering have led many banks outside the region to close their correspondent banking arrangements.

Shipping Industry

Ports of all sizes were built across the Caribbean during the colonial era. The large-scale export of sugar made the Caribbean one of the world's most important shipping areas, and it still is today. Many key shipping routes still pass through the region.

Developing large-scale shipping to compete with other ports in Central and South America faced several challenges in the 1900s. Large-scale operations, high port fees, and Caribbean governments' hesitation to privatize ports put Caribbean shipping at a disadvantage. Many places in the Caribbean are suitable for building deepwater ports for commercial container ships or large cruise ships. The deepwater port at Bridgetown, Barbados, was finished by British investors in 1961. A more recent deepwater port project was completed by Hong Kong investors in Grand Bahama in the Bahamas.

Some Caribbean islands benefit from "flag of convenience" policies used by foreign merchant fleets. This means ships register in Caribbean ports. Registering ships at "flag of convenience" ports is protected by the Law of the Sea and other international agreements. These agreements leave the enforcement of labor, tax, health and safety, and environmental laws to the country where the ship is registered. In practice, this often means such rules rarely lead to penalties against the merchant ship. The Cayman Islands, Bahamas, Antigua, Bermuda, and St. Vincent are among the top 11 flags of convenience in the world. However, this practice has also been a disadvantage for Caribbean islands because it applies to cruise ships too. Cruise ships register outside the Caribbean and can therefore avoid Caribbean enforcement of local laws and regulations.

Timeline of Key Events

- 1492: Spanish arrive on the Lucayan Archipelago, Hispaniola, and Cuba.

- 1493: Spanish arrive on Dominica, Guadeloupe, Montserrat, Antigua, Saint Martin, Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, Jamaica.

- 1496: Spanish found Santo Domingo; colonization of Hispaniola begins.

- 1498: Spanish arrive on Trinidad, Tobago, Grenada, Margarita Island.

- 1499: Spanish arrive on Curaçao, Aruba, Bonaire.

- 1502: Spanish arrive on Martinique.

- 1508: Spanish colonization of Puerto Rico and Aruba begins.

- 1509: Spanish colonization of Jamaica begins.

- 1511: Spanish found Baracoa; colonization of Cuba begins.

- 1520: Spaniards remove the last native people from the Lucayan Archipelago (population of 40,000 in 1492).

- 1525: Spanish colonization of Margarita Island begins.

- 1526: Spanish colonization of Bonaire begins.

- 1527: Spanish colonization of Curacao begins.

- 1536: Portuguese arrive on Barbados.

- 1592: Spanish colonization of Trinidad begins.

- 1623: English colonization of Saint Kitts begins.

- 1627: English colonization of Barbados begins.

- 1628: English colonization of Nevis begins.

- 1631: Dutch colonization of Saint Martin begins.

- 1632: English colonization of Montserrat and Antigua begins.

- 1634: Dutch conquer Spanish Curaçao.

- 1635: French colonization of Guadeloupe and Martinique begins.

- 1636: Dutch conquer Spanish Aruba and Bonaire.

- 1648: English colonization of The Bahamas begins.

- 1649: French colonization of Grenada begins.

- 1650: English colonization of Anguilla begins.

- 1654: Dutch colonization of Tobago begins.

- 1655: English conquer Spanish Jamaica.

- 1681: English colonization of Turks and Caicos begins.

- 1697: By the Peace of Ryswick, Spain gives the western third of Hispaniola (Haiti) to France.

- 1719: French colonization of Saint Vincent (Antilles) begins.

- 1734: English colonization of Cayman Islands begins.

- 1797: British conquer Spanish Trinidad.

|

See Also

In Spanish: Historia del Caribe para niños

In Spanish: Historia del Caribe para niños

- Cartography of Latin America

- General History of the Caribbean

- History of the British West Indies

- Influx of disease in the Caribbean

- Territorial evolution of the Caribbean