Hernán Cortés facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hernán Cortés

|

|

|---|---|

18th-century portrait of Cortés based on the one sent by the conqueror to Paolo Giovio, which has served as a model for many of his representations since the 16th century

|

|

| 1st and 3rd Governor of New Spain | |

| In office 13 August 1521 – 24 December 1521 |

|

| Monarch | Charles I of Spain |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Cristóbal de Tapia |

| In office 30 December 1521 – 12 October 1524 |

|

| Preceded by | Cristóbal de Tapia |

| Succeeded by | Triumvirate: Alonso de Estrada Rodrigo de Albornoz Alonso de Zuazo |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Hernando Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano

1485 Medellín, Castile |

| Died | December 2, 1547 (aged 61–62) Castilleja de la Cuesta, Castile |

| Nationality | Castilian |

| Spouses |

Catalina Suárez

(m. 1516; died 1522)Juana de Zúñiga

(m. 1529) |

| Domestic partners | La Malinche Isabel Moctezuma |

| Children | Don Martín Cortés, 2nd Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca Doña María Cortés Doña Catalína Cortés Doña Juana Cortės Martín Cortés Leonor Cortés Moctezuma |

| Occupation | Conquistador |

| Known for | Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, Spanish conquest of Honduras |

| Signature | |

Hernán Cortés (born 1485 – died December 2, 1547) was a Spanish conquistador. This means he was a leader in the Spanish effort to explore and conquer new lands. He led an important expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire. This brought a large part of what is now Mexico under the rule of the King of Castile in the early 1500s. Cortés was part of the first group of Spanish explorers and conquerors who started the Spanish colonization of the Americas.

Born in Medellín, Spain, to a family of lesser nobles, Cortés decided to seek adventure and wealth in the New World. He first traveled to Hispaniola (an island now shared by Haiti and the Dominican Republic) and then to Cuba. In Cuba, he received an encomienda, which was a grant of land that included the right to use the labor of the native people living there. He also served as a magistrate (a type of judge) in a Spanish town.

In 1519, Cortés was chosen to lead an expedition to the mainland. He helped pay for this trip himself. However, the Governor of Cuba, Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, changed his mind and tried to stop the expedition at the last moment. Cortés ignored these orders and sailed anyway.

When he arrived on the continent, Cortés used a smart strategy. He made alliances with some indigenous people against others. He also used a native woman, Doña Marina, as an interpreter. She later had his first son. When the Governor of Cuba sent people to arrest Cortés, he fought them and won. He then added their troops to his own forces. Cortés wrote letters directly to the king, asking to be recognized for his successes instead of being punished for disobeying orders. After he defeated the Aztec Empire, Cortés was given the title of Marqués del Valle de Oaxaca. In 1541, Cortés returned to Spain, where he died six years later.

Contents

Early Life and Journey to the New World

Hernán Cortés was born in 1485 in a small town called Medellín, Spain. His father, Martín Cortés de Monroy, was a captain from a respected family, but they were not very wealthy. His mother was Catalína Pizarro Altamirano. Through his mother, Hernán was a distant cousin of Francisco Pizarro, who later conquered the Inca Empire in Peru.

As a child, Cortés was described as pale and often sick. At 14, he went to study Latin. He later spent time training as a notary, which gave him knowledge of legal rules. This legal knowledge helped him later when he needed to justify his actions in Mexico.

Cortés was described as determined and a bit rebellious. News of Christopher Columbus's discoveries in the New World made him want to seek adventure. He planned to sail to the Americas with Nicolás de Ovando, the new Governor of Hispaniola. However, Cortés was injured and couldn't go. He spent the next year traveling around Spain's southern ports. Finally, in 1504, he left for Hispaniola and became a colonist.

Life in Hispaniola and Cuba

When Cortés arrived in Santo Domingo, Hispaniola, at age 18, he registered as a citizen. This gave him land for farming and a building plot. The governor gave him an encomienda, which meant he had the right to use the labor of certain native people. He was also appointed as a notary. For the next five years, he worked to establish himself in the colony. In 1506, Cortés helped in the Spanish conquests of Hispaniola and Cuba. He was rewarded with a large estate and native workers.

In 1511, Cortés joined Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar's expedition to conquer Cuba. Velázquez later became the Governor of New Spain. Cortés became a clerk responsible for making sure the Spanish Crown received one-fifth of the expedition's profits. Velázquez was impressed with Cortés and gave him important political jobs. Cortés became the governor's secretary and was twice appointed as a municipal magistrate (a local official) in Santiago de Cuba.

Cortés became a wealthy man in Cuba, owning land and native workers for his mines and cattle. However, his relationship with Governor Velázquez became difficult. Cortés married Catalina Xuárez, who was Velázquez's sister-in-law. This marriage was somewhat forced by Velázquez.

Cortés missed the first two Spanish expeditions to Mexico. But in October 1518, Velázquez appointed him as Captain-General of a new expedition. Velázquez soon changed his mind because he was jealous of Cortés. However, Cortés quickly gathered more men and ships from other Cuban ports and left before Velázquez could stop him.

Conquering the Aztec Empire (1519–1521)

In February 1519, Cortés ignored Governor Velázquez's orders and sailed to Mexico. He had about 11 ships, 500 men, 13 horses, and some cannons. He landed on the Yucatán Peninsula in Maya territory. There, he met Gerónimo de Aguilar, a Spanish priest who had survived a shipwreck and lived with the Maya. Aguilar had learned the local language and could translate for Cortés.

Cortés was not an experienced military leader, but he was very effective. He won early battles against the native people along the coast. In March 1519, he officially claimed the land for the Spanish king. He then went to Tabasco, where he fought and won another battle. The defeated natives gave him twenty young indigenous women, who he converted to Christianity.

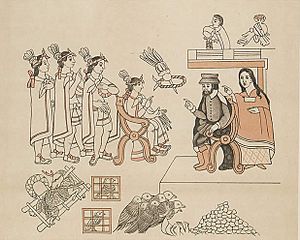

One of these women was La Malinche, who became his partner and the mother of his son, Martín. Malinche knew both the Nahuatl language (spoken by the Aztecs) and the Maya language. This allowed Cortés to communicate with the Aztecs through Aguilar and Malinche.

In July 1519, Cortés's men took over Veracruz. By doing this, Cortés declared that he was no longer under the authority of the Governor of Cuba, but directly under the King Charles. To make sure his men couldn't retreat, Cortés sank his own ships.

March to Tenochtitlán

In Veracruz, Cortés met some Aztec officials and asked to meet Moctezuma II, the ruler of the Aztec Empire. Moctezuma refused many times, but Cortés was determined. In mid-August 1519, Cortés marched towards Tenochtitlán, the Aztec capital. He had 600 soldiers, 15 horsemen, 15 cannons, and hundreds of native allies.

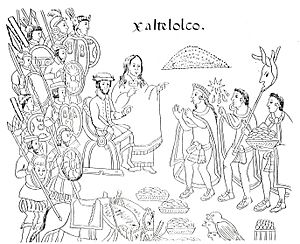

On the way, Cortés made alliances with other native groups, like the Totonacs and the Tlaxcalans. The Tlaxcalans first fought the Spanish, but after several battles, they realized the Spanish were enemies of Moctezuma. So, they decided to join forces with Cortés.

In October 1519, Cortés and his men, along with about 1,000 Tlaxcalan allies, marched to Cholula. This was the second-largest city in central Mexico. Cortés, fearing a trap, ordered a violent attack on thousands of unarmed nobles in the city's main plaza. He then partly burned the city.

By the time Cortés reached Tenochtitlán, his army was very large. On November 8, 1519, Moctezuma II welcomed them peacefully. Moctezuma allowed Cortés to enter the island city, hoping to learn their weaknesses and defeat them later.

Moctezuma gave the Spanish many gold gifts. This did not calm them, but instead made them want even more treasure. Cortés soon learned that some Spaniards on the coast had been killed by Aztecs. He decided to take Moctezuma hostage in his own palace, ruling Tenochtitlán indirectly through him.

Meanwhile, Governor Velázquez sent another expedition, led by Pánfilo de Narváez, to stop Cortés. Narváez arrived in Mexico in April 1520 with 1,100 men. Cortés left 200 men in Tenochtitlán and went to fight Narváez. Cortés won, even though he had fewer men, and convinced Narváez's soldiers to join him. Back in Tenochtitlán, one of Cortés's officers, Pedro de Alvarado, caused a violent event in the Great Temple, which started a rebellion.

Cortés quickly returned to Tenochtitlán. Facing an angry population, Cortés decided to escape to Tlaxcala. During the Noche Triste (Sad Night) on June 30 – July 1, 1520, the Spanish barely escaped Tenochtitlán. Many of their men were killed, and much of the treasure and artillery they had taken was lost.

The Fall of Tenochtitlán

After a battle in Otumba, Cortés and his men reached Tlaxcala, having lost 870 men. With help from their allies and new soldiers from Cuba, Cortés's forces finally gained the upper hand. Cortés began a strategy to weaken Tenochtitlán by cutting off its supplies and conquering the Aztecs' allied cities. During the siege, he built small ships (brigantines) on the lake and slowly destroyed parts of the city to avoid street fighting. The Aztec warriors fought bravely, but eventually, the city fell.

The siege of Tenochtitlán ended with a Spanish victory and the destruction of the city. This happened when Cuauhtémoc, the new ruler of Tenochtitlán, was captured on August 13, 1521. Cortés claimed the Aztec Empire for Spain and renamed the city Mexico City. From 1521 to 1524, Cortés personally governed Mexico.

Governing New Spain and Later Life

After his great success, King Charles appointed Cortés as governor, captain general, and chief justice of the new territory, which was called "New Spain". However, the king also appointed four royal officials to help govern, which meant Cortés was closely watched. Cortés began building Mexico City on the ruins of the Aztec capital. He destroyed Aztec temples and buildings and rebuilt them into what became the most important European city in the Americas.

Cortés oversaw the founding of new cities and extended Spanish rule across New Spain. He set up the encomienda system, giving land and native workers to his followers as rewards for their conquest. However, others who arrived later complained that Cortés showed favoritism.

In 1523, the Crown sent another military force to conquer a northern part of Mexico. This was a setback for Cortés, who felt he was a victim of a conspiracy by his enemies. He wrote to the King, who eventually stopped this interference.

Royal Recognition and Family Life

Even though Cortés had disobeyed the Governor of Cuba, his amazing success was rewarded by the king. In 1525, he was given a special coat of arms, a sign of great honor. This coat of arms showed symbols of the Spanish Empire, a lion (representing his efforts), three crowns for the Aztec emperors he defeated, and the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán. It also showed symbols of the seven city-states he conquered.

Cortés's first wife, Catalina Suárez, arrived in New Spain around 1522. Their marriage was difficult because she was related to Governor Velázquez, Cortés's enemy. Catalina died under mysterious circumstances in November 1522. She had no children with Cortés. Cortés had several children with indigenous women, including a son named Martín with Doña Marina.

In 1526, Cortés built a grand home, the Palace of Cortés in Cuernavaca. In 1529, he was given the noble title of don and, more importantly, Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca. He then married a Spanish noblewoman, Doña Juana de Zúñiga. They had three children, including another son also named Martín. This second Martín was his first legitimate son and became his heir, inheriting his title and estate.

Cortés and the "Spiritual Conquest"

Cortés believed that converting native peoples to Christianity was very important. He asked the Spanish king to send Franciscan and Dominican friars to Mexico to teach Christianity to the large native population. He preferred friars over other priests because he thought friars would set a better example and help the native people truly convert.

The Franciscans arrived in May 1524. There were twelve of them, known as the Twelve Apostles of Mexico. It is said that Cortés himself met them, kneeling at their feet. This story showed everyone, including the native people, that Cortés's earthly power was less important than the spiritual power of the friars. Cortés and the Franciscans had a strong alliance. Many Franciscans saw him as a "new Moses" for conquering Mexico and allowing Christianity to spread.

Expedition to Honduras and Return to Spain

From 1524 to 1526, Cortés led an expedition to Honduras. He defeated Cristóbal de Olid, who had claimed Honduras for himself. Fearing that Cuauhtémoc might start a rebellion in Mexico, Cortés brought him along to Honduras. Sadly, Cuauhtémoc was executed during this journey. Cortés also ordered the arrest of Governor Velázquez, believing he was behind Olid's actions. This made the Spanish Crown worried about Cortés's growing power.

The king appointed an official to investigate Cortés's actions and even arrest him. Cortés once said it was "more difficult to contend against [his] own countrymen than against the Aztecs."

In 1528, Cortés returned to Spain to speak directly to King Charles V. He presented himself with great style and answered all the accusations against him. He showed that he had given more than the required one-fifth of the gold to the Crown. He also explained how he had spent a lot of money to build Mexico City. The king received him with honor and gave him the order of Santiago.

Although he kept his land and titles, Cortés was not made governor again. He never held another important administrative job in New Spain.

Return to Mexico and Later Explorations

Cortés returned to Mexico in 1530 with new titles. While he still had military authority, Antonio de Mendoza was appointed as the first viceroy in 1535 to manage New Spain's civil affairs. This sharing of power often led to disagreements.

Cortés retired to his estates at Cuernavaca, south of Mexico City. There, he focused on building his palace and exploring the Pacific. He also acquired several silver mines.

In 1536, Cortés explored the northwestern part of Mexico and discovered the Baja California peninsula. The Gulf of California was originally named the Sea of Cortés by Francisco de Ulloa in 1539. This was Cortés's last major expedition.

Final Years and Death

After his exploration of Baja California, Cortés returned to Spain in 1541. He hoped to deal with lawsuits against him for debts and abuse of power. When he met the emperor, who asked who he was, Cortés famously replied, "I am a man who has given you more provinces than your ancestors left you cities."

The emperor allowed Cortés to join a large expedition against Algiers in 1541. During this campaign, Cortés almost drowned in a storm.

Cortés had spent a lot of his own money on expeditions and was now heavily in debt. He tried to claim money from the royal treasury in 1544, but his request was ignored for three years. Disappointed, he decided to return to Mexico in 1547. However, he fell ill with dysentery and died in Castilleja de la Cuesta, Spain, on December 2, 1547, at the age of 62.

In his will, Cortés made sure his many children, both those born in and out of marriage, and their mothers were well cared for. He asked that his remains eventually be buried in Mexico. Before he died, the Pope officially recognized four of his children, including Martín, the son he had with Doña Marina (La Malinche), who was said to be his favorite.

After his death, Cortés's body was moved more than eight times. He was first buried in Spain. In 1566, his body was sent to New Spain and buried in a church in Texcoco, Mexico. In 1629, his remains were moved to a Franciscan church in Mexico City. In 1794, his bones were moved to the "Hospital de Jesus" (which Cortés himself founded), where a statue and a tomb were made for him.

In 1823, after Mexico gained independence, there was concern that his body might be disrespected. So, his tomb was removed, and his bones were hidden. Many people thought they had been sent out of Mexico. It wasn't until November 24, 1946, that his bones were rediscovered. They were confirmed by the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) and placed back in the same hospital, with a bronze inscription and his coat of arms.

Children

Hernán Cortés had several children.

His children born outside of marriage:

- doña Catalina Pizarro, born around 1514-1515 in Cuba or New Spain. Her mother was an indigenous woman from Cuba, Leonor Pizarro.

- don Martín Cortés, born in Coyoacán in 1522. His mother was doña Marina (La Malinche). He was known as the "First Mestizo" (meaning of mixed European and indigenous heritage).

- don Luis Cortés, born in 1525. His mother was doña Antonia or Elvira Hermosillo.

- doña Leonor Cortés Moctezuma, born around 1527-1528 in Mexico City. Her mother was the Aztec princess Isabel Moctezuma, daughter of Moctezuma II.

- doña María Cortés de Moctezuma, also daughter of an Aztec princess.

Cortés married twice:

- First, in Cuba, to Catalina Suárez Marcaida. She died in 1522, and they had no children.

- Second, in 1529, to doña Juana Ramírez de Arellano de Zúñiga, a Spanish noblewoman. They had:

- don Luis Cortés y Ramírez de Arellano, born in 1530, died shortly after birth.

- doña Catalina Cortés de Zúñiga, born in 1531, died shortly after birth.

- don Martín Cortés y Ramírez de Arellano, born in 1532, became the 2nd Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca.

- doña María Cortés de Zúñiga, born between 1533 and 1536.

- doña Catalina Cortés de Zúñiga, born between 1533 and 1536, died unmarried.

- doña Juana Cortés de Zúñiga, born between 1533 and 1536.

Images for kids

-

Bust of Hernán Cortés in the General Archive of the Indies in Seville.

See also

In Spanish: Hernán Cortés para niños

In Spanish: Hernán Cortés para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |