History of Mexico facts for kids

The history of Mexico goes back more than 3,000 years. People first lived in Mexico over 13,000 years ago. In central and southern Mexico, known as Mesoamerica, many complex native civilizations grew and fell. Mexico later became a unique country with many different cultures.

Ancient Mesoamerican civilizations created writing systems using symbols. They used these to record the history of their leaders and conquests. The time before Europeans arrived in Mexico is called the prehispanic or pre-Columbian era.

After Mexico became independent from the Spanish Empire in 1821, the country faced a lot of political trouble. France even took control in the 1860s, with help from some Mexicans, but was later defeated. The late 1800s saw peaceful growth, but the Mexican Revolution in 1910 led to a difficult civil war. After peace returned in the 1920s, Mexico's economy grew steadily, and its population increased quickly.

Contents

- Ancient Civilizations of Mexico

- Major Ancient Civilizations

- Spanish Conquest of the Aztec Empire

- New Spain: The Colonial Period

- Independence Era (1808–1829)

- The Age of Santa Anna (1829–1854)

- Liberals and Conservatives Fight (1855–1876)

- Porfiriato (1876–1910)

- Mexican Revolution (1910–1920)

- Revolutionary Consolidation (1920–1940)

- "Revolution to Evolution" (1940–1970)

- Recent History (1970–1994)

- Contemporary Mexico

- See also

Ancient Civilizations of Mexico

Large and advanced civilizations grew in central and southern Mexico, a region called Mesoamerica. These civilizations, which rose and fell over thousands of years, shared some common features:

- They had big cities.

- They built huge structures like temples, palaces, and ball courts.

- Society was divided into important groups like religious leaders, political leaders, warriors, and merchants. Most people were commoners who farmed.

- Commoners gave goods and labor to the leaders.

- They relied on farming, and sometimes hunting and fishing. They did not have animals like cows or horses for herding before Europeans arrived.

- They had trade networks and markets.

These civilizations developed in an area without big rivers for travel, without animals to carry heavy loads, and with tough land that made moving people and goods difficult. Native civilizations created complex calendars for rituals and tracking the sun. They also had a strong understanding of astronomy and developed writing systems using symbols.

We know about Mexico's history before the Spanish arrived thanks to archaeologists and experts who study ancient writings and native histories. They look at old native books, especially those from the Aztec, Maya, and Mixtec cultures.

Writings by Spanish conquerors and native historians from after the conquest are also important sources of information about Mexico at that time.

Only a few picture books, called codices, from the Maya, Mixtec, and Mexica cultures of the later Post-Classic period still exist. However, much progress has been made in understanding Maya archaeology and their writings.

Early Settlements in Mexico

People were once thought to have been in Mesoamerica as far back as 40,000 years ago, based on ancient footprints found in the Valley of Mexico. However, later studies using radiocarbon dating showed this date might not be correct. It is still unclear if 23,000-year-old campfire remains found in the Valley of Mexico are the oldest human traces in Mexico.

The first people in Mexico found a climate much milder than today's. The Valley of Mexico had several large ancient lakes, like Lake Texcoco, surrounded by thick forests. Deer lived there, but most animals were small land creatures, fish, and other lake animals. These conditions encouraged early people to live by hunting and gathering.

Native peoples in western Mexico started to grow maize (corn) from wild grasses between 5,000 and 10,000 years ago.

The diet of ancient central and southern Mexico was very diverse. It included domesticated corn, squashes like pumpkin, common beans, tomatoes, peppers, pineapples, chocolate, and tobacco. Corn, squash, and beans, often called "The Three Sisters," were the main foods.

Religion and Beliefs

Mesoamericans had gods and religious beliefs, but they were very different from what we might think of today. They believed that everything in the world—the earth, sun, moon, stars, animals, plants, water, and mountains—was a sign of the supernatural. Gods and goddesses were often shown in stone carvings, pottery, wall paintings, and in their special books called Maya, Aztec, and Mixtec codices.

Their spiritual world was huge and very complex. However, many gods were shared across different civilizations and were worshipped for a long time. They often had different names or features in different places, but their meaning was the same across cultures and time. Large masks with open jaws and scary faces, made of stone or stucco, were often placed at temple entrances. These symbolized a cave or opening in the mountains, allowing access to Mother Earth's depths and the shadowy paths to the underworld.

Beliefs connected to the jaguar and jade were very important throughout Mesoamerica. Jade, with its green color, was seen as a symbol of life and fertility, just like water. The jaguar, being quick, strong, and fast, was especially linked to warriors and as spirit guides for shamans (spiritual healers). Even with differences in time or location, the main parts of this religious system were shared among ancient Mesoamerican people.

This openness to accepting new gods alongside existing ones might have helped Christianity spread in Mesoamerica. New gods didn't immediately replace the old ones; they first joined the growing family of deities or blended with existing ones that seemed similar. The Christianization of Europe also followed similar patterns of taking in and changing existing beliefs.

We know a lot about the Aztec religion because early friars (religious brothers) worked to convert native peoples to Christianity. Writings by Franciscans Fray Toribio de Benavente Motolinia and Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, and Dominican Fray Diego Durán, recorded much about Nahua religion. They believed understanding old practices was key to successfully converting the native populations.

Ancient Writing Systems

Mesoamerica is the only place in the Americas where native writing systems were created and used before Europeans arrived. These writing systems ranged from simple "picture-writing" to complex systems that could record speech and stories. They all shared some key features that made them look and work differently from other writing systems around the world.

Many native books (codices) were lost or destroyed. However, texts from Aztec codices, Mayan codices, and Mixtec codices still exist. These are very important to scholars studying the prehispanic era.

Because there was already a tradition of writing before the Spanish arrived, when Spanish friars taught Mexican natives to write their own languages, especially Nahuatl, an alphabet-based writing system took hold. This was used in official documents for legal cases and other legal papers. The formal use of native language documents continued until Mexico's independence in 1821. Starting in the late 1900s, scholars have studied these native language documents to learn about the economy, culture, and language of the colonial period. This study is now called the "New Philology."

Major Ancient Civilizations

During the time before Columbus, many city-states, kingdoms, and empires in Mexico competed for power and fame. Five major civilizations emerged in ancient Mexico: the Olmec, Maya, Teotihuacan, Toltec, and Aztec. Unlike other native Mexican societies, these civilizations (except for the Maya, who were politically divided) spread their power and culture across Mexico and beyond.

They gathered power and influenced trade, art, politics, technology, and religion. Over 3,000 years, other regional powers formed alliances with them or went to war against them. But almost all found themselves under their influence.

Olmecs (1500–400 BCE)

The Olmec first appeared along the Atlantic coast in what is now the state of Tabasco between 1500 and 900 BCE. The Olmecs were the first Mesoamerican culture to have a clear artistic and cultural style. They may also have been the society that invented writing in Mesoamerica. By the Middle Preclassic Period (900–300 BCE), Olmec art styles were used as far away as the Valley of Mexico and Costa Rica.

Maya Civilization

Maya cultural features, like the rise of the ahau (king), can be seen from 300 BCE onward. In the centuries before the classical period, Maya kingdoms appeared in an area stretching from the Pacific coasts of southern Mexico and Guatemala to the northern Yucatán Peninsula. The Maya society, which was more equal in earlier centuries, slowly changed into one controlled by a wealthy elite. This elite began building large ceremonial temples and complexes.

The earliest known long-count date, 199 AD, marks the start of the classical period. During this time, Maya kingdoms supported millions of people. Tikal, the largest kingdom, had 500,000 residents, though most kingdoms were much smaller, with fewer than 50,000 people. The Maya speak a diverse group of languages called Mayan.

Teotihuacan Civilization

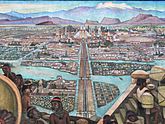

Teotihuacan is a huge archaeological site in the Basin of Mexico. It has some of the largest pyramid structures built in the Americas before Columbus. Besides its pyramids, Teotihuacan is known for its large living areas, the Avenue of the Dead, and many colorful, well-preserved murals. Teotihuacan also made a special thin orange pottery style that spread across Mesoamerica.

The city is thought to have been founded around 100 BCE and continued to be built until about 250 CE. It may have lasted until sometime between the 7th and 8th centuries CE. At its peak, perhaps in the first half of the 1st millennium CE, Teotihuacan was the largest city in the Americas before Columbus. At this time, it may have had more than 200,000 people, making it one of the world's largest cities. Teotihuacan even had multi-story apartment buildings for its large population.

The civilization and culture linked to the site are also called Teotihuacan or Teotihuacano. While it's debated if Teotihuacan was the center of an empire, its influence across Mesoamerica is clear. Evidence of Teotihuacano presence can be seen at many sites in Veracruz and the Maya region. The Aztecs may have been influenced by this city. The ethnic group of Teotihuacan's inhabitants is also debated. Possible groups include the Nahua, Otomi, or Totonac. Scholars have also suggested that Teotihuacan was a multi-ethnic state.

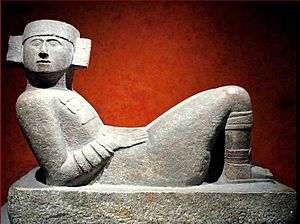

Toltec Civilization

The Toltec culture was an ancient Mesoamerican culture that ruled a state centered in Tula, Hidalgo, during the early post-classic period (around 800–1000 AD). The later Aztec culture saw the Toltecs as their smart and cultured ancestors. They described Toltec culture from Tollan (the Nahuatl word for Tula) as the best example of civilization. In fact, in the Nahuatl language, the word "Toltec" came to mean "artisan" or skilled craftsman.

Aztec oral stories and picture writings also described the history of the Toltec empire, listing rulers and their achievements. Among modern scholars, it's debated whether these Aztec stories about Toltec history should be trusted as real historical events. While all scholars agree there's a lot of myth in the stories, some believe that by carefully comparing sources, some historical truth can be found. Others think that continuing to analyze these stories as actual history is pointless and prevents true understanding of the culture of Tula, Hidalgo.

Another debate about the Toltecs is how to explain the similarities in architecture and art between the archaeological site of Tula and the Maya site of Chichén Itzá. There is no agreement yet on how much influence one had on the other, or in which direction.

Aztec Empire (1325–1521 AD)

The Nahua peoples started moving into central Mexico in the 6th century AD. By the 12th century, they had set up their main center at Azcapotzalco, the city of the Tepanecs.

The Mexica people arrived in the Valley of Mexico in 1248 AD. They had traveled from the deserts north of the Rio Grande, a journey traditionally said to have taken 100 years. They may have seen themselves as the inheritors of the great civilizations that came before them. What the Aztec initially lacked in political power, they made up for with their ambition and military skill. In 1325, they built what became the largest city in the world at that time, Tenochtitlan.

Aztec religion was based on the belief that their gods needed regular offerings, including human blood, to remain kind. To meet this need, the Aztec performed sacrifices. This belief was common among the Nahuatl people. To get captives during peaceful times, the Aztec used a special kind of ritual warfare called flower war. The Tlaxcalteca, among other Nahuatl nations, were forced into these wars.

In 1428, the Aztec led a war against their rulers from Azcapotzalco, who had controlled most of the Valley of Mexico's people. The revolt was successful, and the Aztecs became the rulers of central Mexico as leaders of the Triple Alliance. This alliance included the city-states of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan.

At their strongest, 350,000 Aztecs ruled over a rich empire that collected tribute from 10 million people. This was almost half of Mexico's estimated population of 24 million. Their empire stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific oceans and into Central America. The empire's expansion westward was stopped by a major military defeat by the Purepecha, who had weapons made of copper. The empire relied on a system of taxation (of goods and services). These were collected through a complex system of tax collectors, courts, and local officials loyal to the Triple Alliance.

By 1519, the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, where modern-day Mexico City now stands, was one of the world's largest cities. It had an estimated population of 200,000 to 300,000 people.

Spanish Conquest of the Aztec Empire

Mexico Before the Spanish Arrived

After exploring the coast, the Spanish began moving inland to conquer new lands. The Spanish crown continued its effort to conquer non-Catholic peoples, which had finished in Spain in 1492. In 1502, near the Gulf of Urabá in modern-day Colombia, Spanish explorers led by Vasco Núñez de Balboa explored and conquered the area near the Atrato River.

They conquered the Chibcha-speaking nations, mainly the Muisca and Tairona native people who lived there. The Spanish founded San Sebastian de Uraba in 1509, but abandoned it within a year. In 1510, they established the first permanent Spanish settlement on the American mainland, Santa María la Antigua del Darién.

The first Europeans to reach what is now Mexico were survivors of a Spanish shipwreck in 1511. Only two, Gerónimo de Aguilar and Gonzalo Guerrero, survived until more Spanish explorers arrived years later. On February 8, 1517, an expedition led by Francisco Hernández de Córdoba left Cuba to explore the southern coast of Mexico.

During this trip, many of Hernández's men were killed, mostly during a battle near Champotón against a Maya army. Hernández himself was injured and died a few days after returning to Cuba. This was the Europeans' first encounter with an American civilization that had buildings and complex societies similar to those in the Old World. Hernán Cortés led a new expedition to Mexico, landing at present-day Veracruz on April 22, 1519. This date marks the start of 300 years of Spanish rule over the region.

Generally, the "Spanish conquest of Mexico" refers to the conquest of central Mesoamerica, where the Aztec Empire was located. The fall of the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, in 1521 was a key event. However, the conquest of other parts of Mexico, like Yucatán, continued long after the Spanish controlled central Mexico. The Spanish conquest of Yucatán was a much longer campaign, from 1551 to 1697, against the Maya peoples in the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico and northern Central America.

After the Conquest

Tenochtitlan was almost completely destroyed by fire and cannon fire. It wasn't certain that Tenochtitlan would become the Spanish capital, but Cortés decided to make it so.

Cortés imprisoned the royal families of the valley. To prevent another revolt, he personally tortured and killed Cuauhtémoc, the last Aztec Emperor, along with Coanacoch, the King of Texcoco, and Tetlepanquetzal, King of Tlacopan.

The Spanish had no intention of giving Tenochtitlan to the Tlaxcalteca. While Tlaxcalteca troops continued to help the Spaniards, and Tlaxcala received better treatment than other native nations, the Spanish eventually broke their agreement. Forty years after the conquest, the Tlaxcalteca had to pay the same taxes as any other native community.

- Political Changes. A small group of Spaniards controlled central Mexico through the existing native rulers of local states (altepetl). These rulers kept their noble status after the conquest if they cooperated with Spanish rule.

- Religious Changes. Cortés immediately banned human sacrifice throughout the conquered empire. In 1524, he asked the Spanish king to send friars from religious orders like the Franciscan, Dominican, and Augustinian to convert the native people to Christianity. This is often called the "spiritual conquest of Mexico." Christian teaching began in the early 1520s and continued into the 1560s. Many friars, especially Franciscans and Dominicans, learned the native languages and recorded aspects of native culture. These records are a main source of our knowledge about them. One of the first 12 Franciscans in Mexico, Fray Toribio de Benavente Motolinia, wrote down his observations of the native people in Spanish. Important Franciscans involved in collecting and preparing native language materials, especially in Nahuatl, include Fray Alonso de Molina and Fray Bernardino de Sahagún.

- Economic Changes. The Spanish colonizers introduced the encomienda system of forced labor. In central Mexico, this built on native traditions of giving tribute and labor to local rulers and to the Aztec empire. Individual Spaniards were given the right to receive tribute and labor from specific native communities, with the local population paying tribute and working. Native communities were pressured for labor and tribute, but they were not enslaved. Their rulers remained native elites, who kept their status under colonial rule and served as useful go-betweens. The Spanish also used forced labor, often outright slavery, in mining.

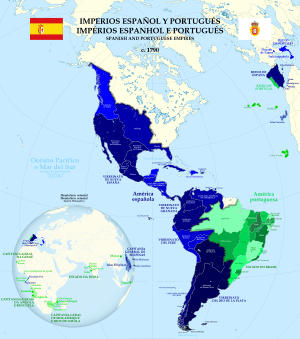

New Spain: The Colonial Period

The capture of Tenochtitlan began a 300-year colonial period. During this time, Mexico was known as "New Spain" and was ruled by a viceroy on behalf of the Spanish king. Colonial Mexico had two main things that attracted Spanish immigrants: (1) many native people, especially in the central area, who could be made to work, and (2) huge mineral wealth, particularly large silver deposits in the northern regions of Zacatecas and Guanajuato. The Viceroyalty of Peru also had these two important features. So, New Spain and Peru were the main centers of Spanish power and wealth until other viceroyalties were created in South America in the late 1700s.

This wealth made Spain the most powerful country in Europe, competing with England, France, and the Netherlands. Spain's silver mines and royal mints produced high-quality coins, the silver peso or Spanish dollar, which became a global currency.

Continued Conquests (1521–1550)

Spain did not immediately control all areas of the Aztec Empire. After Tenochtitlan fell in 1521, it took decades of occasional fighting to conquer the rest of Mesoamerica. This was especially true for the Mayan regions of southern New Spain and into what is now Central America. Spanish conquests in the Zapotec and Mixtec regions of southern Mesoamerica happened relatively quickly.

Outside the settled Mesoamerican civilizations were nomadic northern indios bárbaros ("wild Indians"). These groups fought fiercely against the Spaniards and their native allies, like the Tlaxcalans, in the Chichimeca War (1550–1590). The northern native populations gained mobility using horses that the Spaniards brought to the New World. This region was important to the Spanish because of its rich silver deposits. The Spanish mining towns and the main roads to Mexico City needed to be safe for supplies to go north and silver to go south.

Early Colonial Economy

The most important source of wealth was tribute from native people and forced labor. This was organized in the first years after the conquest of central Mexico through the encomienda system. An encomienda was a grant of labor from a specific native settlement to an individual Spaniard and his family. Conquerors expected to receive these awards. The first Spanish viceroy, Don Antonio de Mendoza, had an Aztec manuscript, the Codex Mendoza, named after him. This book lists the types and amounts of tribute goods from native towns under Aztec rule. The first people to hold encomiendas, called encomenderos, were the conquerors who fought to take Tenochtitlan. Later, their heirs and influential people who weren't conquerors also received them. Forced labor could be used to develop land and industries where the Spanish encomenderos' native workers lived. Land was a less important source of wealth during this early conquest period. Where native labor was scarce or needed extra help, the Spanish brought slaves, often as skilled workers or artisans.

Mixing of Cultures

Europeans, Africans, and native peoples mixed, creating a diverse population called casta in a process known as mestizaje. Mestizos, people of mixed European and native ancestry, make up most of Mexico's population today.

Life in Colonial Mexico (1521–1821)

Colonial Mexico was part of the Spanish Empire and was governed by the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The Spanish crown claimed all of the Western Hemisphere west of the line set between Spain and Portugal by the Treaty of Tordesillas. This included all of North and South America, except for Brazil. The Viceroyalty of New Spain ruled over Spain's northern empire in the Americas. When Spain set up a colony in the Philippines in the late 1500s, the Viceroyalty of New Spain also governed it, as there was more direct contact between Mexico and the Philippines than between the Philippines and Spain.

Hernán Cortés had conquered the Aztec Empire and made New Spain the largest and most important Spanish colony. During the 16th century, Spain focused on conquering areas with large populations that had developed advanced civilizations before Columbus. These populations provided a disciplined workforce and people to convert to Christianity.

Territories with nomadic peoples were harder to conquer. Although the Spanish explored much of North America, looking for the legendary "El Dorado" (a city of gold), they didn't make a big effort to settle the northern desert regions, now part of the United States, until the late 1500s (like Santa Fe in 1598).

Colonial laws, based on native customs but with Spanish history, were introduced. This created a balance between local rule (the Cabildos) and the Crown's power. Higher administrative jobs were closed to natives, even those of pure Spanish blood. The population of New Spain was divided into four main groups, or classes, based on race and birthplace. The most powerful group was the Spaniards, people born in Spain who were sent to rule the colony. Only Spaniards could hold high-level government jobs.

The second group, called criollos, were people of Spanish background but born in Mexico. Many criollos were rich landowners and merchants. But even the wealthiest creoles had little say in government.

The third group, the mestizos, were people with both Spanish and Native ancestors. The word mestizo means "mixed" in Spanish. Mestizos had a much lower position and were looked down upon by both Spaniards and creoles, who believed that people of full European background were superior.

The poorest and most marginalized group in New Spain was the Natives, descendants of the peoples who lived there before Columbus. They had less power and faced harsher conditions than other groups. Natives were forced to work as laborers on the ranches and farms (called haciendas) owned by Spaniards and creoles.

Besides these four main groups, there were also some Africans in colonial Mexico. These Africans were brought in as laborers and had a low status similar to the Natives. They made up about 4% to 5% of the population. Their mixed-race descendants, called mulattoes, eventually grew to represent about 9%.

Economically, New Spain was mainly managed for the benefit of the Empire and its military efforts. Mexico provided more than half of the Empire's taxes and supported the administration of all North and Central America. Competition with Spain was discouraged. For example, growing grapes and olives, which Cortés himself introduced, was banned because Spain feared these crops would compete with its own.

To protect the country from attacks by English, French, and Dutch pirates, and to secure the Crown's income, only two ports were open to foreign trade: Veracruz on the Atlantic and Acapulco on the Pacific. Pirates attacked and looted several cities like Campeche (1557), Veracruz (1568), and Alvarado (1667).

Education was supported by the Crown from the very beginning. Mexico boasts the first primary school (Texcoco, 1523), the first university, the University of Mexico (1551), and the first printing press (1524) in the Americas. Native languages were mainly studied by religious orders in the first centuries. They became official languages in the "Republic of Natives," only to be outlawed and ignored after independence by the dominant Spanish-speaking creoles.

Mexico achieved important cultural milestones during the colonial period. These include the literature of 17th-century nun Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz and Ruiz de Alarcón. There were also beautiful cathedrals, public buildings, forts, and colonial cities like Puebla, Mexico City, Querétaro, and Zacatecas. Many of these are now World Heritage sites.

The blending of native and Spanish cultures led to many of today's famous Mexican traditions. These include tequila (since the 16th century), mariachi music (18th century), jarabe dance (17th century), charros (Mexican cowboys, 17th century), and the highly valued Mexican cuisine, which combines European and native ingredients and cooking methods.

Mexicans born in America (creoles), mixed-race castas, and Natives often disagreed, but all resented the small group of Spaniards born in Spain who held all the political power. By the early 1800s, many American-born Spaniards believed Mexico should become independent from Spain, following the example of the United States. The person who started the revolt against Spain was the Catholic priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla. He is remembered today as the Father of the Nation.

Independence Era (1808–1829)

This period was marked by unexpected events that ended 300 years of Spanish colonial rule. The colony went from being ruled by the rightful Spanish king and his appointed viceroy to an illegitimate king and viceroy put in place by a sudden takeover. Later, Mexico saw the return of the rightful Spanish monarchy, followed by a stalemate with rebel guerrilla forces. Events in Spain again changed the situation in New Spain. Spanish military officers overthrew the absolute king and brought back the liberal Spanish constitution of 1812. Conservatives in New Spain, who had strongly supported the Spanish monarchy, now saw a reason to change course and seek independence. Royal army officer Agustín de Iturbide became a supporter of independence. He convinced rebel leader Vicente Guerrero to join forces, forming the Army of the Three Guarantees. Within six months of this alliance, Spanish rule in New Spain collapsed, and independence was achieved. The idea of a constitutional monarchy with a European royal on the throne did not happen. Instead, creole military officer Iturbide became Emperor Agustín I. His increasingly strict rule upset many, and a takeover overthrew him in 1823. Mexico became a federal republic and created a constitution in 1824. While General Guadalupe Victoria became the first president and served his full term, presidential transitions became less about elections and more about military force. Rebel general and important Liberal politician Guerrero was briefly president in 1829, then removed and killed by his Conservative opponents. In the 20 years since France invaded Spain, Mexico had faced political instability and violence, with more to come until the late 1800s. The presidency changed hands 75 times in the next 50 years. The new republic's situation did not help economic growth or development. Silver mines were damaged, trade was disrupted, and violence continued. Although British merchants set up businesses in major cities, the situation was grim. "Trade was stuck, imports didn't pay, illegal trade pushed prices down, debts went unpaid, merchants suffered many injustices, and operated at the mercy of weak and corrupt governments. Businesses were close to bankruptcy."

Road to Independence

Inspired by the American and French Revolutions, Mexican rebels saw a chance for independence in 1808. This happened when Napoleon invaded Spain and the Spanish king Charles IV was forced to give up his throne. Napoleon put his brother Joseph Bonaparte on the Spanish throne. For Spain and its empire, this created a crisis of who had the right to rule. In Spain, resistance to the French led to the Peninsular War. In New Spain, Viceroy José de Iturrigaray suggested forming a temporary self-governing body, with support from American-born Spaniards on the Mexico City city council. Spaniards born in Spain saw this as a threat to their own power. Gabriel J. de Yermo led a takeover against the viceroy, arresting him in September 1808. Spanish military officer Pedro de Garibay was named viceroy by the Spanish plotters. His time in office was short, from September 1808 to July 1809. He was replaced by Francisco Javier de Lizana y Beaumont, whose term was also brief, until Viceroy Francisco Javier Venegas arrived from Spain. Two days after entering Mexico City on September 14, 1810, Father Miguel Hidalgo called for people to fight in the village of Dolores. Spain was invaded by France, and the Spanish king was removed, with a French king put in his place. Like others in colonial Spanish America, New Spain's viceroy José de Iturrigaray, who sympathized with creoles, tried to create a legitimate government during this time. He was overthrown by powerful Peninsular Spaniards, and strict Spaniards cracked down on any idea of Mexican self-rule. Creoles who had hoped for a path to Mexican self-rule, perhaps within the Spanish Empire, now saw that their only path was independence through rebellion against the colonial government. There were several creole plots. In northern Mexico, Father Miguel Hidalgo, creole militia officer Ignacio Allende, and Juan Aldama met to plan a rebellion. When the plot was discovered in September 1810, Hidalgo called his church members to arms in the village of Dolores, starting a huge rebellion in the Bajío region. It even had support from Filipinos, like the Manila-born engineer and miner Ramon Fabié, who supported Miguel Hidalgo's revolt.

War of Independence, 1810–1821

In 1810, rebel plotters planned a rebellion against the royal government, which was again firmly controlled by Spaniards born in Spain. When the plot was discovered, Father Hidalgo called his parishioners in Dolores to action. This event on September 16, 1810, is now called the "Cry of Dolores" and is celebrated as Independence Day. Shouting "Independence and death to the Spaniards!" about 80,000 poorly organized and armed villagers formed a force that initially swept through Bajío unchecked. The viceroy was slow to react, but once the royal army engaged the untrained, poorly armed, and poorly led crowd, they defeated the rebels. Hidalgo was captured, removed from his priestly duties, and executed. His head was left on a pike in Guanajuato as a warning to other rebels.

Another priest, José María Morelos, took over and was more successful in his fight for a republic and independence. Spain's monarchy was restored in 1814 after Napoleon's defeat, and it fought back, executing Morelos in 1815. The scattered rebels formed guerrilla groups. In 1820, Spanish royal army general, Agustín de Iturbide, switched sides and proposed independence, issuing the Plan of Iguala. Iturbide convinced rebel leader Vicente Guerrero to join this new push for independence. He was impressed by Guerrero's strong personality and ideals, as well as the determination of his soldiers. This included General Isidoro Montes de Oca, a Mexican of Filipino descent, who, with few and poorly armed rebels, defeated the royalist Gabriel from Armijo. They also got enough equipment to properly arm 1,800 freedom fighters who would later earn Iturbide's respect. He was known for his bravery during the siege of Acapulco in 1813, under General José María Morelos y Pavón. Isidoro and his soldiers from Guerrero State, which was settled by immigrants from the Philippines, defeated the royalist army from Spain. Impressed, Iturbide joined forces with Guerrero and demanded independence, a constitutional monarchy in Mexico, continued religious control for the Catholic Church, and equality for Spaniards and those born in Mexico. Royalists who now followed Iturbide's change of sides and rebels formed the Army of the Three Guarantees. Within six months, the new army controlled all of Mexico except the ports of Veracruz and Acapulco. On September 27, 1821, Iturbide and the last viceroy, Juan O'Donojú, signed the Treaty of Córdoba, where Spain granted the demands. O'Donojú had been acting under instructions issued months before these latest events. Spain refused to formally recognize Mexico's independence, and the situation became even more complicated by O'Donojú's death in October 1821.

First Mexican Empire

When Mexico gained independence, the southern part of New Spain also became independent due to the Treaty of Córdoba. So, Central America, including present-day Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and part of Chiapas, were included in the Mexican Empire. Although Mexico now had its own government, there was no major change socially or economically. The formal, legal racial distinctions were removed, but power remained with the white elite. Monarchy was the type of government Mexicans knew, so it's not surprising they chose it initially. The political power of the royal government shifted to the military. The Roman Catholic Church was the other main institution. Both the army and the church lost members with the new government. A sign of the economic decline was the drop in church income from the tithe, a tax on farm output. Mining was especially hard hit. It had driven the colonial economy, but there was much fighting during the war of independence in Zacatecas and Guanajuato, the two most important silver mining sites. Despite Viceroy O'Donojú signing the Treaty of Córdoba granting Mexico its independence, the Spanish government did not recognize it as valid and claimed control over Mexico.

Spain started events that led to Iturbide, the son of a provincial merchant, becoming Emperor of Mexico. With Spain rejecting the treaty and no European royal accepting the offer to be Mexico's monarch, many creoles now decided that having a Mexican as their monarch was acceptable. A local army garrison declared Iturbide emperor. Since the church refused to crown him, the president of the constituent congress did so on July 21, 1822. His long-term rule was doomed. He did not have the respect of the Mexican nobility. Republicans wanted a republic, not a monarchy. The emperor set up all the symbols of a monarchy with a court and fancy robes of power. His increasingly dictatorial actions and silencing of criticism led him to shut down congress. Worried that a brilliant young colonel, Antonio López de Santa Anna, would start a rebellion, the emperor removed him from his command. Instead of obeying, Santa Anna declared a republic and quickly called for congress to meet again. Four days later, he changed his mind about republicanism and simply called for the emperor's removal, in the Plan of Casa Mata. Santa Anna secured the support of rebel general Guadalupe Victoria. The army supported the plan, and the emperor gave up his throne on March 19, 1823.

First Mexican Republic

Those who overthrew the emperor then cancelled the Plan of Iguala, which had called for a constitutional monarchy, as well as the Treaty of Córdoba. This left them free to choose any form of government they could agree on. It was decided to be a federal republic, and on October 4, 1824, the United Mexican States (Spanish: Estados Unidos Mexicanos) was established. The new constitution was partly based on the United States constitution. It guaranteed basic human rights and defined Mexico as a representative federal republic. In this system, government responsibilities were divided between a central government and several smaller units called states. It also declared Catholicism as the official and only religion of the republic. Central America did not join the federal republic and took a separate political path starting July 1, 1823.

Mexico's new, untested government did not bring stability. The army remained the main political power, and the Roman Catholic Church the only religious power. Both the army and the church kept special privileges in the new era. General Guadalupe Victoria was followed in office by General Vicente Guerrero. Guerrero gained the position through a takeover after losing the 1828 elections. The Conservative Party saw a chance to take control and led a counter-takeover under General Anastasio Bustamante, who served as president from 1830 to 1832, and again from 1837 to 1841.

The Age of Santa Anna (1829–1854)

Political Instability

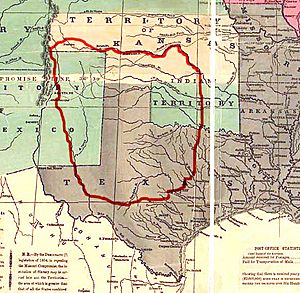

In many parts of Spanish America soon after independence, strong military leaders, or caudillos, controlled politics. This period is often called "The Age of Caudillismo." In Mexico, from the late 1820s to the mid-1850s, the period is often called the "Age of Santa Anna," named after the general and politician, Antonio López de Santa Anna. Liberals (federalists) asked Santa Anna to overthrow conservative President Anastasio Bustamante. After he did, he declared General Manuel Gómez Pedraza (who won the 1828 election) president. Elections were held afterward, and Santa Anna took office in 1832. He served as president 11 times. Constantly changing his political beliefs, in 1834 Santa Anna cancelled the federal constitution. This caused rebellions in the southeastern state of Yucatán and the northernmost part of the northern state of Coahuila y Tejas. Both areas sought independence from the central government. Negotiations and the presence of Santa Anna's army led Yucatán to recognize Mexican sovereignty (self-rule). Then Santa Anna's army turned to the northern rebellion.

The people of Tejas declared the Republic of Texas independent from Mexico on March 2, 1836, at Washington-on-the-Brazos. They called themselves Texans and were led mainly by recent Anglo-American settlers. At the Battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836, Texan militiamen defeated the Mexican army and captured General Santa Anna. The Mexican government refused to recognize Texas's independence.

Comanche Conflict

The northern states became increasingly isolated, economically and politically. This was due to long-lasting Comanche raids and attacks. The native peoples of the north had not recognized the Spanish Empire's claims to the region, nor did they when Mexico became an independent nation. Mexico tried to convince its citizens to settle in the region, but few were willing. Mexico negotiated a contract with Anglo Americans to settle in the area, hoping they would do so in Comanche territory, the Comancheria. In the 1820s, when the United States began to influence the region, New Mexico had already started to question its loyalty to Mexico. By the time of the Mexican–American War, the Comanches had raided and looted large parts of northern Mexico. This led to ongoing poverty, political division, and general frustration with the Mexican government's inability—or unwillingness—to control the Comanches.

In addition to Comanche raids, the First Republic's northern border was troubled by attacks from the Apache people. These groups were supplied with guns by American merchants. Goods like guns and shoes were sold to the Apache. Mexican forces discovered this when they found traditional Apache trails with American shoe prints instead of moccasin prints.

Texas Independence

Soon after gaining independence from Spain, the Mexican government tried to populate its northern territories. It gave large land grants in Coahuila y Tejas to thousands of families from the United States. The condition was that these settlers convert to Catholicism and become Mexican citizens. The Mexican government also banned importing slaves. These conditions were mostly ignored.

A key reason for the government to allow these settlers was the belief that they would (a) protect northern Mexico from Comanche attacks and (b) create a buffer for the northern states against US expansion westward. The policy failed on both counts: the Americans tended to settle far from the Comanche raiding zones and used the Mexican government's failure to stop the raids as an excuse to declare independence.

The Texas Revolution or Texas War of Independence was a military conflict between Mexico and settlers in the Texas part of the Mexican state Coahuila y Tejas.

The war lasted from October 2, 1835, to April 21, 1836. However, a naval war between Mexico and Texas continued into the 1840s. Bad feelings between the Mexican government and the American settlers in Texas, as well as many Texas residents of Mexican ancestry, began with the Siete Leyes (Seven Laws) of 1835. This was when Mexican President and General Antonio López de Santa Anna ended the federal Constitution of 1824 and announced the more centralizing 1835 constitution in its place.

War began in Texas on October 2, 1835, with the Battle of Gonzales. Early Texian Army successes at La Bahia and San Antonio were soon followed by crushing defeats at the same locations a few months later. The war ended at the Battle of San Jacinto where General Sam Houston led the Texian Army to victory over a part of the Mexican Army under Santa Anna, who was captured soon after the battle. The end of the war resulted in the creation of the Republic of Texas in 1836. In 1845, the U.S. Congress approved Texas's request to become a state.

Mexican-American War (1846–1848)

After a Mexican attack on a U.S. army group in disputed territory, the U.S. Congress declared war on May 13, 1846. Mexico followed on May 23. The Mexican–American War took place in two main areas: the western campaign (aimed at California) and the Central Mexico campaign (aimed at capturing Mexico City).

In March 1847, U.S. President James K. Polk sent an army of 12,000 volunteer and regular U.S. Army soldiers under General Winfield Scott to the port of Veracruz. The 70 ships of the invading forces arrived at the city on March 7 and began a naval attack. After landing his men, horses, and supplies, Scott began the Siege of Veracruz.

The city, which was still walled at that time, was defended by Mexican General Juan Morales with 3,400 men. Veracruz fought back as best it could with artillery from land and sea, but the city walls were destroyed. After 12 days, the Mexicans surrendered. Scott marched west with 8,500 men, while Santa Anna dug in with artillery and 12,000 troops on the main road halfway to Mexico City. At the Battle of Cerro Gordo, Santa Anna was outsmarted and defeated.

Scott pushed on to Puebla, Mexico's second-largest city, which surrendered without resistance on May 1. The citizens were against Santa Anna. After the Battle of Chapultepec (September 13, 1847), Mexico City was occupied. Scott became its military governor. Many other parts of Mexico were also occupied. Some Mexican units fought bravely. One of the well-remembered groups was six young Military College cadets (now considered Mexican national heroes), who fought to the death defending their college during the Battle of Chapultepec.

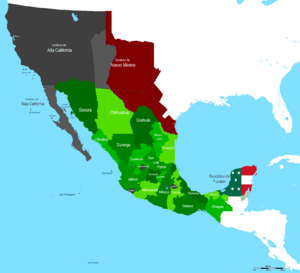

The war ended with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. This treaty stated that (1) Mexico must sell its northern territories to the US for US$15 million; (2) the US would give full citizenship and voting rights, and protect the property rights of Mexicans living in the given territories; and (3) the US would take on $3.25 million in debt owed by Mexico to Americans. The war was Mexico's first encounter with a modern, well-organized, and well-equipped army. Mexico's defeat has been blamed on its internal problems, including disunity and disorganization.

End of Santa Anna's Rule

Despite Santa Anna's role in the disaster of the Mexican–American War, he returned to power again. When the U.S. wanted an easier railroad route to California south of the Gila River, Santa Anna sold the Gadsden Strip to the US for $10 million in the Gadsden Purchase in 1853. This loss of more territory angered Mexicans, but Santa Anna claimed he needed the money to rebuild the army after the war. In the end, he kept or wasted most of it. Liberals finally united and successfully rebelled against his rule. They announced the Plan of Ayutla in 1854, forcing Santa Anna into exile. Liberals came to power and began making the reforms they had long planned.

Liberals and Conservatives Fight (1855–1876)

Liberals removed conservative Santa Anna in the Plan of Ayutla. They aimed to bring in liberal reforms through a series of separate laws, and then in a new constitution that included them. Mexico experienced a civil war and a foreign intervention that set up a monarchy with the support of Mexican conservatives. The fall of Maximilian of Mexico's empire and his execution in 1867 brought a period of relative peace, but the economy struggled during the Restored Republic. Historically, this era has often shown liberals as building a new, modern nation and conservatives as opposing that vision. Starting in the late 20th century, historians are writing more balanced analyses of both liberals and conservatives.

Important liberal politicians in the 1850s and 1860s included Benito Juárez, Juan Álvarez, Ignacio Comonfort, Miguel Lerdo de Tejada, Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada, Melchor Ocampo, José María Iglesias, Santiago Vidaurri, Manuel Doblado, and Santos Degollado. Key conservatives of that time were generals Félix Zuloaga, Miguel Miramón, Leonardo Márquez, Tomás Mejía, José Mariano Salas, as well as Juan N. Almonte, son of independence leader José María Morelos.

Plan of Ayutla

La Reforma began with the final overthrow of Santa Anna in the Plan of Ayutla in 1855. Moderate Liberal Ignacio Comonfort became president. The Moderados (Moderates) tried to find a middle ground between the nation's liberals and conservatives. There is less agreement on when the Reforma ended.

Common dates are 1861, after the liberal victory in the Reform War; 1867, after the republican victory over the French intervention in Mexico; and 1876 when Porfirio Díaz overthrew president Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada. Liberalism was a dominant intellectual force in Mexico into the 20th century. Liberals supported reform and favored republicanism, capitalism, and individualism. They fought to reduce the Church's role in education, land ownership, and politics. Also importantly, liberals aimed to end the special status of native communities by ending their communal ownership of land.

Constitution of 1857

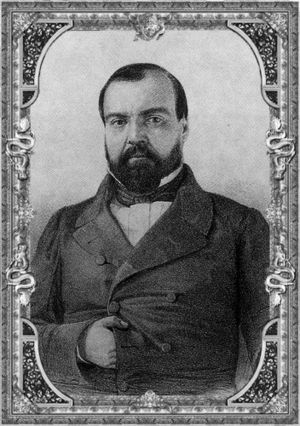

Liberal Colonel Ignacio Comonfort became president in 1855 after a revolt based in Ayutla overthrew Santa Anna. Comonfort was a moderate who tried and failed to keep a shaky alliance of radical and moderate liberals together. Radical liberals wrote the Constitution of 1857. This constitution reduced the power of the president, included the laws of the Reform, and limited the traditional powers of the Catholic Church. It granted religious freedom, only stating that the Catholic Church was the preferred faith. The anti-clerical radicals won a major victory with the constitution's approval because it weakened the Church and gave voting rights to men who didn't own property. The constitution was opposed by the army, the clergy, and other conservatives, as well as moderate liberals like Comonfort. With the Plan of Tacubaya in December 1857, conservative General Félix Zuloaga led a takeover in the capital in January 1858, creating a separate government in Mexico City. Comonfort resigned the presidency and was replaced by the President of the Supreme Court, Benito Juárez, who became President of the Republic, leading Mexican liberals.

War of Reform (1857–1861)

The revolt led to the Reform War (December 1857 to January 1861). This war became increasingly bloody and divided the nation's politics. Many Moderates, convinced that the Church's political power had to be limited, joined the Liberals.

For some time, the Liberals and Conservatives ran separate governments at the same time. The Conservatives were in Mexico City, and the Liberals were in Veracruz. The war ended with a Liberal victory, and liberal President Benito Juárez moved his government to Mexico City.

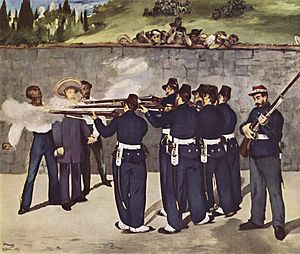

French Intervention and Second Mexican Empire (1861–1867)

In 1862, France invaded Mexico. They wanted to collect debts that the Juárez government had stopped paying. But their bigger goal was to put a ruler under French control on the throne. They chose a member of the Habsburg family, which had ruled Spain until 1700. Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian of Austria was made Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico. He had support from the Catholic Church, conservative wealthy people, and some native communities. Although the French lost an early battle (the Battle of Puebla on May 5, 1862, now celebrated as Cinco de Mayo), they eventually defeated the Mexican army and put Maximilian on the throne. The Mexican-French monarchy set up its government in Mexico City, ruling from the National Palace.

Maximilian's wife was Empress Carlota of Mexico, and they chose Chapultepec Castle as their home. Some historians praise Maximilian for his liberal reforms, his desire to help the people of Mexico, and his refusal to abandon his loyal followers. Others accused him of using the nation's resources for himself and his allies. This included favoring Napoleon III's plans to exploit mines in the northwest and grow cotton.

Maximilian was a liberal, a fact that Mexican conservatives seemingly didn't know when he was chosen to lead the government. He favored a limited monarchy that would share power with a democratically elected congress. This was too liberal for conservatives, while liberals refused to accept any monarch, seeing Benito Juárez's republican government as the rightful one. This left Maximilian with few strong allies in Mexico. Meanwhile, Juárez remained head of the republican government. He continued to be recognized by the United States, which was fighting its own Civil War (1861–65). At that point, the U.S. couldn't directly help Juárez against the French until 1865.

France never made a profit in Mexico, and its Mexican expedition became increasingly unpopular. Finally, in the spring of 1865, after the US Civil War ended, the US demanded that French troops leave Mexico. Napoleon III quietly agreed. In mid-1867, despite repeated Imperial losses in battle to the Republican Army and decreasing support from Napoleon III, Maximilian chose to stay in Mexico rather than return to Europe. He was captured and executed along with two Mexican supporters, an event famously shown in a painting by Édouard Manet. Juárez remained in office until his death in 1872.

Restored Republic (1867–1876)

In 1867, with the monarchy defeated and Emperor Maximilian executed, the republic was restored, and Juárez was reelected. He continued to carry out his reforms. In 1871, he was elected a second time, which upset his opponents within the Liberal party, who thought reelection was undemocratic. Juárez died the following year and was replaced by Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada.

Part of Juárez's reforms included making the country fully secular (non-religious). The Catholic Church was not allowed to own property other than places of worship and monasteries. Education and marriage were put under the control of the state.

Porfiriato (1876–1910)

The rule of Porfirio Díaz (1876–1911) focused on law and order, stopping violence, and modernizing the country. Diaz was a former muleteer (someone who drives mules) from Oaxaca who became a military commander for the liberals in the 1860s. Diaz took power in a sudden takeover in 1876, set up a dictatorship, and ruled with the help of wealthy landowners. He kept good relations with the United States and Great Britain, which led to a big increase in foreign investment, especially in mining. The general standard of living steadily improved. He followed a harsh "laissez-faire" (hands-off) economic idea that mainly benefited the already privileged social classes. Diaz was overthrown by the Mexican Revolution in 1911 and died in exile.

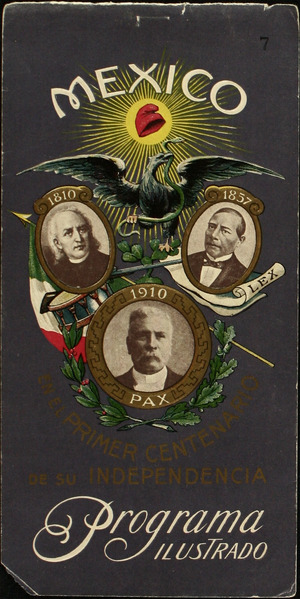

This time of relative prosperity is known as the Porfiriato. As old ways were challenged, city Mexicans debated national identity, rejecting native cultures, and embracing French culture after the French were removed from Mexico. They also faced the challenge of creating a modern nation-state through industrialization and scientific development. Díaz stayed in power by fixing elections and censoring the press. Possible rivals were removed, and popular generals were moved to new areas so they couldn't build a strong base of support. Banditry (robbery) on roads leading to major cities was largely stopped by the "Rurales", a police force controlled by Díaz. Banditry remained a major threat in more distant areas because the Rurales had fewer than 1,000 men. Díaz was a smart military leader and liberal politician who built a national network of supporters. He maintained a stable relationship with the Catholic Church by avoiding enforcing constitutional laws against the clergy. The country's infrastructure greatly improved through increased foreign investment from Britain and the US, and a strong, active central government. Increased tax money and better management greatly improved public safety, public health, railways, mining, industry, foreign trade, and national finances. Díaz modernized the army and stopped some banditry. After 50 years of slow growth, where income per person was only a tenth of developed nations like Britain and the US, the Mexican economy took off under Diaz. Under his rule, it grew at an annual rate of 2.3% (1877 to 1910), which was high by world standards.

Order, Progress, and Dictatorship

Díaz reduced the Army from 30,000 to under 20,000 men. This meant a smaller part of the national budget went to the military. The army was modernized, well-trained, and had some of the latest technology. The Army had too many high-ranking officers, with 5,000 officers, many of them elderly but politically well-connected veterans of the wars of the 1860s.

The political skills Díaz used so well before 1900 faded. He and his closest advisors were less open to talking with younger leaders. His announcement in 1908 that he would retire in 1911 made many people feel that Díaz was leaving and that new groups needed to be formed. He still ran for reelection. To show U.S. support, Díaz and William Taft planned a meeting in El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, for October 16, 1909. This was a historic first meeting between a Mexican and a U.S. president, and the first time an American president would cross into Mexico. Both sides agreed that the disputed Chamizal strip between El Paso and Ciudad Juárez would be neutral territory with no flags during the meeting. However, the meeting drew attention to this area and led to assassination threats and other serious security concerns. On the day of the meeting, Frederick Russell Burnham, a famous scout, and Private C. R. Moore, a Texas Ranger, found a man with a hidden palm pistol standing near the El Paso Chamber of Commerce building along the parade route. Burnham and Moore captured and disarmed the assassin just a few feet from Díaz and Taft. Both presidents were unharmed, and the meeting took place. At the meeting, Díaz told John Hays Hammond, "Since I am responsible for bringing several billion dollars in foreign investments into my country, I think I should continue in my position until a competent successor is found." Díaz was re-elected after a very controversial election. However, he was overthrown in 1911 and forced into exile in France after army units rebelled.

Economy During the Porfiriato

Financial stability was achieved by José Yves Limantour (1854–1935), Mexico's Secretary of Finance from 1893 to 1910. He led the well-educated experts known as Científicos, who believed in modernity and strong finances. Limantour increased foreign investment, supported free trade, balanced the budget for the first time, and created a budget surplus by 1894. However, he could not stop the rising cost of food, which angered the poor.

The American Panic of 1907 was an economic downturn that caused a sudden drop in demand for Mexican copper, silver, gold, zinc, and other metals. Mexico, in turn, reduced its imports of horses and mules, mining machinery, and railroad supplies. The result was an economic depression in Mexico in 1908–1909 that dampened optimism and increased unhappiness with the Díaz government.

Mexico had few factories by 1880, but then industrialization took hold in the Northeast, especially in Monterrey. Factories produced machinery, textiles, and beer, while smelters processed ores. Good rail links with the nearby US gave local business owners from seven wealthy merchant families an advantage over more distant cities. New federal laws in 1884 and 1887 allowed corporations to be more flexible. By the 1920s, American Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO), an American firm controlled by the Guggenheim family, had invested over 20 million pesos and employed nearly 2,000 workers smelting copper and making wire to meet the demand for electrical wiring in the US and Mexico.

Modernization Efforts

Those who wanted to modernize insisted that public schools and non-religious education should lead the way. They believed science should replace religious schooling by the Catholic Church. They reformed elementary schools by making them uniform, non-religious, and logical. These reforms matched international trends in teaching methods. To break old peasant habits that were seen as hindering industrialization, reforms emphasized children's punctuality, hard work, and health. In 1910, the National University opened as an elite school for the next generation of leaders.

Cities were rebuilt with modern architects favoring the latest Western European styles, especially the Beaux-Arts style. This was meant to symbolize a break with the past. A very visible example was the Federal Legislative Palace, built from 1897 to 1910.

Rural Unrest

Historian John Tutino studied the impact of the Porfiriato in the highland basins south of Mexico City. This area later became the heartland of the Zapatista movement during the Revolution. Population growth, railways, and land being owned by only a few families led to a business expansion that weakened the traditional power of villagers. Young men felt unsure about the traditional roles they expected to fill as heads of households. At first, this anxiety showed up as violence within families and communities. But, after Díaz's defeat in 1910, villagers expressed their anger in revolutionary attacks on local elites who had benefited most from the Porfiriato. The young men became more radical, fighting for their traditional roles concerning land, community, and family leadership.

Mexican Revolution (1910–1920)

Quick facts for kids

United Mexican States

Estados Unidos Mexicanos

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1911–1928 | |||||||||||

Map of zones of control during the Mexican Revolution as of 1915

|

|||||||||||

| Government | Revolutionary federal presidential republic | ||||||||||

| Constitutionalist president | |||||||||||

|

• 1911

|

Francisco León de la Barra | ||||||||||

|

• 1911–1913

|

Francisco Madero | ||||||||||

|

• 1913

|

Pedro Lascuráin | ||||||||||

| Conventionist president | |||||||||||

|

• 1914–1915

|

Eulalio Gutiérrez | ||||||||||

|

• 1915

|

Roque González Garza | ||||||||||

|

• 1915

|

Francisco Lagos Cházaro | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

|

• Mexican Revolution begins

|

20 November 1910 | ||||||||||

|

• Established

|

25 May 1911 | ||||||||||

| February 1913 | |||||||||||

| October 1914 | |||||||||||

| 5 February 1917 | |||||||||||

| 22 April 1920 | |||||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

30 November 1928 | ||||||||||

|

• Foundation of the National Revolutionary Party

|

4 March 1929 | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

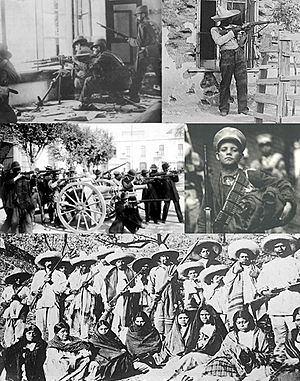

The Mexican Revolution is a general term for big political and social changes in the early 20th century. Most experts believe it lasted from 1910 to 1920. It started with the unfair election of Porfirio Díaz in 1910 and ended with the election of General Alvaro Obregón in December 1920. Other countries, especially the United States, had important economic and strategic interests in Mexico's power struggles.

The Revolution became more widespread, radical, and violent. Revolutionaries wanted big social and economic changes. They aimed to strengthen the government and weaken conservative groups like the Church, rich landowners, and foreign business owners.

Some scholars see the creation of the Mexican Constitution of 1917 as the end of the revolution. "Economic and social conditions improved according to revolutionary policies, so the new society took shape within official revolutionary institutions," with the constitution providing that framework. Organized labor gained significant power, as seen in Article 123 of the Constitution of 1917. Land reform in Mexico was made possible by Article 27. Economic nationalism was also enabled by Article 27, limiting foreign ownership of businesses. The Constitution also further restricted the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico. Putting these restrictions into practice in the late 1920s led to the Cristero War. A ban on presidents being re-elected was put into the Constitution and became practice. Political succession was achieved in 1929 with the creation of the Partido Nacional Revolucionario (PNR). This political party dominated Mexico's politics for the rest of the 20th century and is now called the Institutional Revolutionary Party.

A major result of the revolution was the end of the Federal Army in 1914. It was defeated by the revolutionary forces of different groups in the Mexican Revolution. The Mexican Revolution involved many ordinary people. At first, it was based on farmers who demanded land, water, and a more representative national government. Wasserman notes that:

- "Ordinary people participated in the revolution and its aftermath in three ways. First, they raised local issues like access to land, taxes, and village self-rule, often with the help of local leaders. Second, common people became soldiers to fight in the revolution. Third, the local issues raised by farmers and workers shaped national discussions on land reform, the role of religion, and many other topics."

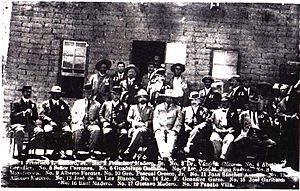

1910 Election and Popular Rebellion

Porfirio Díaz announced in an interview with a US journalist, James Creelman, that he would not run for president in 1910. At that point, he would be 80 years old. This started a lot of political activity by potential candidates, including Francisco I. Madero, a member of one of Mexico's richest families. Madero was part of the Anti-Reelectionist Party, whose main goal was to end the Díaz government. But Díaz changed his mind and ran again. He created the office of vice president, which could have helped with presidential transitions. But Díaz chose a running mate, Ramón Corral, who was not popular politically, instead of a popular military man, Bernardo Reyes, or a popular civilian, Francisco I. Madero. He sent Reyes on a "study mission" to Europe and jailed Madero. Official election results said Díaz won almost all votes, and Madero received only a few hundred. This fraud was too obvious, and riots broke out. Uprisings against Díaz happened in the fall of 1910, especially in northern Mexico and the southern state of Morelos. A political plan written by Madero, the Plan of San Luis Potosí, helped unite opposing forces. In it, he called on the Mexican people to take up arms and fight against the Díaz government. The uprising was set for November 20, 1910. Madero escaped from prison to San Antonio, Texas, where he began preparing to overthrow Díaz—an action now considered the start of the Mexican Revolution. Díaz tried to use the army to stop the revolts, but most of the high-ranking generals were old men close to his age. They did not act quickly or strongly enough to stop the violence. Revolutionary forces, led by Emiliano Zapata in the South, Pancho Villa and Pascual Orozco in the North, and Venustiano Carranza, defeated the Federal Army.

Díaz resigned in May 1911 "for the sake of the peace of the nation." The terms of his resignation were written in the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez. This treaty also called for a temporary president and new elections. Francisco León de la Barra served as interim president. The Federal Army, though defeated by the northern revolutionaries, was kept together. Francisco I. Madero, whose 1910 Plan of San Luis Potosí had helped gather forces against Díaz, accepted the political agreement. He campaigned in the presidential elections of October 1911, won clearly, and became president in November 1911.

Madero's Presidency and Opposition (1911–1913)

After Díaz resigned and a brief interim presidency by a high-level official from the Díaz era, Madero was elected president in 1911.

The revolutionary leaders had many different goals. Revolutionary figures ranged from liberals like Madero to radicals like Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa. Because of this, it was impossible to agree on how to organize the government that came from the successful first phase of the revolution. This disagreement over political ideas quickly led to a struggle for control of the government, a violent conflict that lasted more than 20 years.

Counter-Revolution and Civil War (1913–1915)

Madero was removed from power and killed in February 1913 during the Ten Tragic Days. General Victoriano Huerta, one of Díaz's former generals, and a nephew of Díaz, Félix Díaz, plotted with the US ambassador to Mexico, Henry Lane Wilson, to overthrow Madero and bring back Díaz's policies.

Within a month of the takeover, rebellions spread in Mexico. The most notable were led by the governor of Coahuila, Venustiano Carranza, along with old revolutionaries like Pancho Villa who had been demobilized by Madero. The northern revolutionaries fought under the name of the Constitutionalist Army, with Carranza as the "First Chief" (primer jefe).

In the south, Emiliano Zapata continued his rebellion in Morelos under the Plan of Ayala. This plan called for taking land from large owners and giving it to peasants. Huerta offered peace to Zapata, who refused it.

Huerta convinced Pascual Orozco, whom he had fought while serving the Madero government, to join Huerta's forces. The Huerta government was supported by business interests in Mexico (both foreign and local), wealthy landowners, the Roman Catholic Church, and the German and British governments. The Federal Army became a tool of the Huerta government, growing to about 200,000 men. Many were forced into service and most were poorly trained.

The US did not recognize the Huerta government. However, from February to August 1913, it placed an arms embargo (ban on weapons sales) on Mexico. This embargo exempted the Huerta government, thereby favoring it against the rising revolutionary forces. But President Woodrow Wilson sent a special envoy to Mexico to check the situation. Reports on the many rebellions convinced Wilson that Huerta could not keep order. Weapons stopped flowing to Huerta's government, which helped the revolutionary cause.

The US Navy entered the Gulf Coast, occupying Veracruz in April 1914. Although Mexico was in a civil war at the time, the US intervention united Mexican forces against the US. Foreign powers helped arrange the US withdrawal at the Niagara Falls peace conference. The US timed its pullout to support the Constitutionalist group under Carranza.

Initially, the forces in northern Mexico were united under the Constitutionalist banner. Talented revolutionary generals served the civilian First Chief Carranza. Pancho Villa began to break away from supporting Carranza as Huerta was leaving power. The split was not just personal; it was mainly because Carranza was too politically conservative for Villa. Carranza was not only a leftover from the Díaz era, but also a rich hacienda owner whose interests were threatened by Villa's more radical ideas, especially on land reform. Zapata in the south was also against Carranza due to his stance on land reform.

In July 1914, Huerta resigned under pressure and went into exile. His resignation marked the end of an era because the Federal Army, which was very ineffective against the revolutionaries, stopped existing.

With Huerta gone, the revolutionary groups decided to meet. They wanted to make "a last-ditch effort to avoid more intense warfare than what removed Huerta." Called to meet in Mexico City in October 1914, revolutionaries who opposed Carranza's influence successfully moved the meeting to Aguascalientes. The Convention of Aguascalientes did not bring together the different victorious groups, but it was a brief pause in the revolutionary violence. The break between Carranza and Villa became final during the convention. Instead of First Chief Carranza being named president of Mexico, General Eulalio Gutiérrez was chosen. Carranza and Obregón left Aguascalientes with much smaller forces than Villa's. The convention declared Carranza in rebellion against it, and civil war resumed. This time, it was between revolutionary armies that had fought together to remove Huerta.

Villa allied with Zapata to form the Army of the Convention. Their forces separately moved on the capital and captured Mexico City in 1914, which Carranza's forces had abandoned. The famous picture of Villa sitting in the presidential chair in the National Palace, and Zapata, is a classic image of the Revolution. Villa is reported to have told Zapata that the presidential "chair is too big for us." The alliance between Villa and Zapata did not work in practice beyond this first victory against the Constitutionalists. Zapata returned to his southern stronghold in Morelos, where he continued to fight a guerrilla war under the Plan of Ayala. Villa prepared to win a decisive victory against the Constitutionalist Army under Obregón.

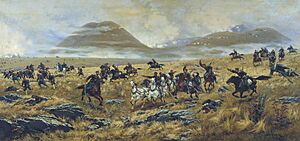

The two rival armies of Villa and Obregón met from April 6–15, 1915, in the Battle of Celaya. Villa's cavalry charges were met by Obregón's smart, modern military tactics. The Constitutionalist victory was complete. Carranza emerged in 1915 as Mexico's political leader with a victorious army to keep him in that position. Villa retreated north, seemingly fading from political importance. Carranza and the Constitutionalists solidified their position as the winning faction, with Zapata remaining a threat until his assassination in 1919.

Constitutionalists in Power (1915–1920)

Venustiano Carranza announced a new constitution on February 5, 1917. The Mexican Constitution of 1917, with important changes made in the 1990s, still governs Mexico.

On January 19, 1917, a secret message (the Zimmermann Telegram) was sent from the German foreign minister to Mexico. It suggested joint military action against the United States if war broke out. The offer included military aid to Mexico to reclaim territory lost during the Mexican–American War, specifically the American states of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. Carranza's generals told him that Mexico would lose to its much more powerful neighbor. Zimmermann's message was intercepted and published. This caused outrage in the US and helped lead to an American declaration of war against Germany in early April. Carranza then formally rejected the offer, and the threat of war with the US lessened.

Carranza was killed in 1920 during a conflict among his former supporters over who would replace him as president.

Revolutionary Consolidation (1920–1940)

Northern Generals as Presidents

Three generals from Sonora, Álvaro Obregón, Plutarco Elías Calles, and Adolfo de la Huerta, controlled Mexico in the 1920s. Their experiences in Mexico's northwest, described as a "savage pragmatism," came from a sparsely populated region with conflicts with native groups, a secular culture, and independent, business-focused ranchers and farmers. This was different from the traditional farming of the densely populated, strongly Catholic native and mestizo peasants of central Mexico. Obregón was the most powerful of the three, as the leading general in the Constitutionalist Army who had defeated Pancho Villa. All three were also skilled politicians and administrators. In Sonora, they had "formed their own professional army, supported and allied themselves with labor unions, and expanded government authority to promote economic development." Once in power, they applied this on a national level.

Obregón's Presidency (1920–1924)

Obregón, Calles, and de la Huerta rebelled against Carranza in the Plan of Agua Prieta in 1920. After the temporary presidency of Adolfo de la Huerta, elections were held, and Obregón was elected for a four-year presidential term. Besides being the Constitutionalists' most brilliant general, Obregón was a clever politician and a successful businessman. His government managed to include many parts of Mexican society, except for the most conservative clergy and wealthy landowners. He was a revolutionary nationalist, holding seemingly contradictory views as a socialist, a capitalist, a Jacobin, a spiritualist, and someone who admired America.

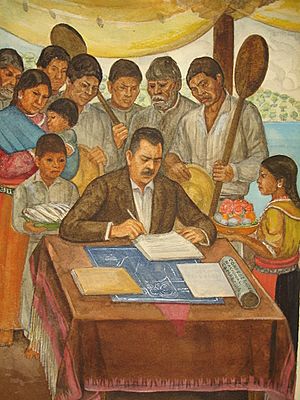

He was able to successfully put into action policies that came from the revolutionary struggle. In particular, successful policies included: bringing urban, organized labor into political life through CROM (a labor union), improving education and Mexican cultural production under José Vasconcelos, advancing land reform, and taking steps toward giving women civil rights. He faced several main tasks as president, mostly political. First was strengthening the central government's power and limiting regional strongmen (caudillos). Second was getting diplomatic recognition from the United States. Third was managing the presidential change in 1924 when his term ended. His administration began building what one scholar called "an enlightened despotism," meaning a ruling belief that the state knew what needed to be done and needed full power to achieve its mission. After nearly a decade of violence from the Mexican Revolution, reconstruction led by a strong central government offered stability and a path to renewed modernization.

Obregón knew his government needed to be recognized by the United States. With the Mexican Constitution of 1917, the Mexican government had the power to take control of natural resources. The U.S. had significant business interests in Mexico, especially oil. The threat of Mexican economic nationalism to big oil companies meant that diplomatic recognition might depend on Mexico compromising on how it applied the constitution. In 1923, as Mexican presidential elections approached, Obregón seriously began negotiating with the U.S. government. The two governments signed the Bucareli Treaty. This treaty resolved questions about foreign oil interests in Mexico, mostly in favor of U.S. interests. In return, Obregón's government gained U.S. diplomatic recognition. With that, weapons and ammunition began flowing to revolutionary armies loyal to Obregón.

Since Obregón had named his fellow Sonoran general, Plutarco Elías Calles, as his successor, Obregón was choosing someone "little known nationally and unpopular with many generals." This blocked the ambitions of other revolutionaries, especially his old comrade Adolfo de la Huerta. De la Huerta started a serious rebellion against Obregón. But Obregón again showed his brilliance as a military strategist. He now had weapons and even air support from the United States to brutally suppress the rebellion. Fifty-four former Obregonistas were shot during the event. Vasconcelos resigned from Obregón's cabinet as minister of education.

Although the Constitution of 1917 had stronger anti-clerical articles than the previous constitution, Obregón largely avoided direct conflict with the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico. Since political opposition parties were essentially banned, the Catholic Church "filled the political void and played the part of a substitute opposition."

Calles's Presidency (1924–1928)