Maya script facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Maya script |

|

|---|---|

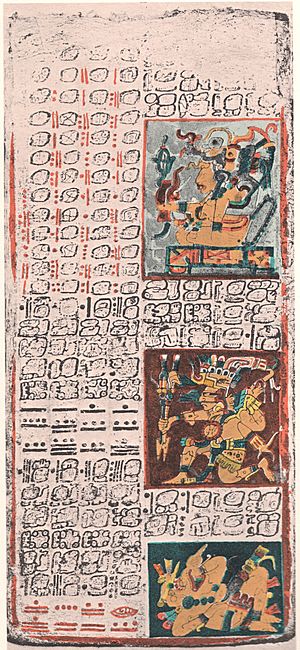

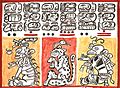

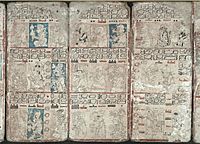

Pages 6, 7, and 8 of the Dresden Codex, showing letters, numbers, and the images that often accompany Maya writing

|

|

| Type | Logosyllabic |

| Spoken languages | Mayan languages |

| Time period | 3rd century BCE to 16th century CE |

| Unicode range | None (tentative range U+15500–U+159FF) |

| ISO 15924 | Maya |

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | |

The Maya script, also known as Maya glyphs, was the writing system used by the ancient Maya civilization in Mesoamerica. It is the only ancient writing system from this region that we can mostly understand today. The oldest Maya writings found are from around 300 BCE in San Bartolo, Guatemala.

Maya writing was used continuously until the Spanish conquest of the Maya in the 16th and 17th centuries. It used logograms (symbols for whole words) along with syllable signs. This is a bit like how modern Japanese writing works. Early European explorers called it "hieroglyphics" because it looked a little like Egyptian hieroglyphs. However, the two systems are not related.

Today, most Mayan languages are written using the Latin alphabet. But recently, there has been a growing interest in bringing back the Maya glyph system.

Contents

Languages of Maya Writing

Most ancient Maya books and texts were written by scribes. These scribes were usually part of the Maya priesthood. They wrote in a special language called Classic Maya. This was a fancy version of an old language called Chʼoltiʼ language.

It's possible that important Maya people spoke Classic Maya across the whole Maya area. But texts were also written in other Mayan languages. These languages were from places like the Petén and Yucatán, especially Yucatec. Sometimes, the script might have been used for Mayan languages from the Guatemalan Highlands.

How Maya Writing Works

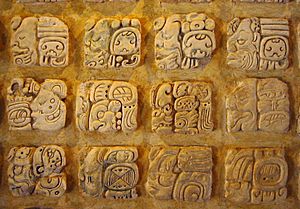

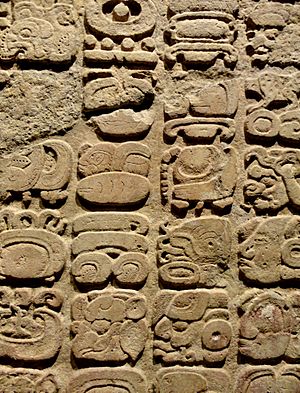

Maya writing used many detailed glyphs. These were carefully painted on pottery, walls, and paper books called codices. They were also carved into wood or stone, and shaped in stucco. Carved and shaped glyphs were painted, but the paint usually wore off.

Today, experts can read the sound of about 80% of Maya writing. They can understand the meaning of about 60% of it. This is enough to get a good idea of how it worked.

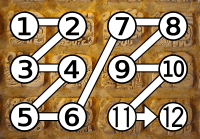

Maya texts were usually written in blocks. These blocks were arranged in columns that were two blocks wide. Each block often stood for a noun or a verb. You would read the blocks within the columns from left to right, then top to bottom. This continued until all columns were read. Inside a block, glyphs were arranged top-to-bottom and left-to-right. Sometimes, glyphs were combined into one symbol. Maya writing could also be in a single row or column, or in an 'L' or 'T' shape. These different layouts were used to fit the surface being written on.

The Maya script was a logosyllabic system. This means individual symbols could represent a whole word (a morpheme) or a syllable. Often, the same symbol could be used for both. For example, a calendar symbol could mean the word manikʼ or the syllable chi.

Syllable glyphs were originally symbols for single-syllable words. These words usually ended in a vowel or a soft consonant. For example, the symbol for 'fish fin' was read as [kah]. It then came to represent the syllable ka. These syllable glyphs had two main jobs. They helped to make clear which meaning a word symbol had if it had more than one. They also helped write grammar parts like verb endings that didn't have their own word symbols. For instance, bʼalam ('jaguar') could be written as one word symbol, bʼalam. It could also be written with added syllables, like ba-bʼalam or bʼalam-ma. Or it could be written completely with syllable signs as bʼa-la-ma.

Some syllable glyphs sounded the same but looked different. For example, there were six different glyphs for the common third person pronoun u-.

Emblem Glyphs: Royal Titles

An "emblem glyph" is a special royal title. It includes a place name followed by the word ajaw. Ajaw was a Classic Maya word for "lord." Sometimes, the title also included the word kʼuhul, meaning "holy" or "divine." So, it would be "holy [placename] lord."

It's important to know that an "emblem glyph" isn't just one single glyph. It could be spelled using many different syllable or word signs. The words kʼuhul and ajaw could also be spelled in several ways. The term "emblem glyph" was created when experts couldn't read Classic Maya writing yet. They used it to describe repeating parts of the written stories.

A scholar named Heinrich Berlin first identified this title in 1958. He noticed that these "emblem glyphs" had a main sign and two smaller signs. The smaller signs are now read as kʼuhul ajaw. Berlin saw that the main sign changed from one Maya city to another. He suggested that these main signs identified different cities, their ruling families, or the areas they controlled.

Later, other scholars debated if these glyphs referred to cities or to the rulers themselves. Today, we understand that "emblem glyphs" were titles for Maya rulers. They also had a connection to a specific place. These glyphs helped people understand who was in charge and where they came from.

Maya Numbers

The Maya used a number system based on twenty (vigesimal). This is different from our system, which is based on ten. They only used whole numbers. For simple counting, they used dots and bars. A dot meant 1, and a bar meant 5. A shell symbol was used for zero. Numbers from 6 to 19 were made by combining dots and bars. They could be written side-by-side or stacked up.

Numbers larger than 19 were written vertically, from bottom to top. Each level represented a power of 20. The bottom number showed values from 0 to 19. The second level from the bottom showed how many groups of 20 there were. So, that number was multiplied by 20. The third level showed how many groups of 400 (20 x 20) there were, so it was multiplied by 400. This system allowed the Maya to calculate very large numbers. This was important for their calendar and astronomy.

History of Maya Writing

For a long time, people thought the Maya might have learned writing from the Olmec or Epi-Olmec culture. These cultures used a script called the Isthmian script. However, in 2005, new murals were found. These murals showed that Maya writing is much older than previously thought. Now, it seems possible that the Maya were the first to invent writing in Mesoamerica. Most experts agree that the Maya developed the only complete writing system in Mesoamerica.

Knowledge of Maya writing continued into the early colonial period. Some early Spanish priests who came to Yucatán reportedly learned it. But a bishop named Diego de Landa ordered the destruction of written Maya works. He wanted to get rid of pagan practices. Because of this, many Maya codices (ancient books) were destroyed.

Later, Landa tried to create a Maya "alphabet" to help convert the Maya to Christianity. This was called the de Landa alphabet. The Maya didn't actually write with an alphabet. But Landa recorded a list of Maya sounds and symbols. For a long time, scholars thought this list was useless. However, it later became a very important tool for deciphering the Maya script. The problem was that the Spanish alphabet and Maya writing were very different. Landa's Maya scribe didn't understand the Spanish letter names. So, Landa would ask things like, "write 'ha': 'hache–a'." He then wrote down a part of the result as "H." In reality, it was written as a-che-a in Maya glyphs.

Landa also helped create a way to write the Yukatek Maya language using the Latin alphabet. This was the first time a Mayan language was written with Latin letters.

For many years, only three Maya codices were known to have survived the Spanish conquest. In 2015, a fourth one, the Grolier Codex, was confirmed as real. Most surviving Maya texts are found on pottery from tombs. They are also on monuments and stelae (carved stone slabs) found at ancient sites. These sites were often abandoned or buried before the Spanish arrived.

Knowledge of the Maya writing system was lost, probably by the end of the 16th century. People became interested in it again in the 19th century. This happened after published stories about ruined Maya sites came out.

Deciphering Maya Glyphs

Figuring out Maya writing has been a long and hard job. In the 1800s and early 1900s, researchers managed to decode the Maya numbers. They also understood parts of texts about astronomy and the Maya calendar. But most of the other texts remained a mystery for a long time.

In the 1930s, Benjamin Whorf suggested that Maya writing had phonetic (sound-based) elements. Even though some of his ideas were later proven wrong, his main point was right. Maya hieroglyphs were indeed phonetic, or more specifically, syllabic. This idea was later supported by Yuri Knorozov (1922–1999). Knorozov played a huge role in decoding Maya writing. In 1952, he published a paper saying that Landa's "alphabet" was made of syllabic symbols, not alphabetic ones. He kept improving his methods and published translations of Maya manuscripts.

In the 1960s, more progress was made. Scholars started to uncover the records of Maya rulers. Since the early 1980s, experts have shown that most of the unknown symbols are part of a syllabary. Because of this, reading Maya writing has moved forward very quickly.

A big breakthrough happened in 1959. A Russian-American scholar named Tatiana Proskouriakoff studied dates on stone monuments at Piedras Negras. She realized these dates showed events in a person's life, not just religious or astronomy facts. This was true for many Maya inscriptions. It showed that the Maya wrote down the actual histories of their rulers. Suddenly, the Maya had a written history, just like other cultures around the world.

Even though it was clearer what was on many inscriptions, they still couldn't be read word-for-word. But more progress came in the 1960s and 1970s. Scholars used many different ways to decode the script. This included looking for patterns, using Landa's "alphabet," and Knorozov's discoveries. Many different types of experts helped, like archaeologists, art historians, and linguists.

A new wave of discoveries happened in the early 1970s. This was especially true at the first Mesa Redonda de Palenque conference in December 1973. A group of scholars, including Linda Schele, Floyd Lounsbury, and Peter Mathews, worked together. In just one afternoon, they figured out most of the list of rulers for Palenque. They identified a sign as an important royal title. This helped them identify and "read" the life stories of six Palenque kings.

From that point on, progress was very fast. Scholars like J. Kathryn Josserand and Nick Hopkins found new words for the Maya vocabulary. Some older scholars resisted these new ideas for a while. But a major event in 1986 helped change minds. This was an art exhibition called "The Blood of Kings: A New Interpretation of Maya Art." It showed a wide audience the new understanding of Maya hieroglyphs. People could now read and understand a real history of ancient America. This new understanding also made sense of many Maya artworks whose meaning was unclear before. It showed that the Maya had a history like other human societies, with wars, power struggles, and complex beliefs.

Today, over 90 percent of Maya texts can be read quite accurately. As of 2020, we know at least one phonetic glyph for almost every syllable.

| (ʼ) | b | ch | chʼ | h | j | k | kʼ | l | m | n | p | s | t | tʼ | tz | tzʼ | w | x | y | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| e | Yes | Yes | Yes | ? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ? | Yes | ? | Yes | |

| i | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| o | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| u | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ? | Yes | Yes |

Maya Syllables

The table below shows Maya syllables. They are made of a consonant and a vowel. The top row has the vowels. The left column has the consonants and how to say them. The apostrophe (ʼ) means a glottal stop (a sound like the break in "uh-oh"). Some cells have many different pictures. This means there were different ways to write the same syllable. Empty cells mean we don't know those characters yet.

| a | e | i | o | u | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| b |    |

|

|

||

| ch /tš/ |

|

|

|

||

| ch’ |  |

|

|||

| h /h/ |

|

||||

| j /x/ |

|

|

|

|

|

| k |  |

|

|

|

|

| k’ |  |

|

|

|

|

| l |  |

|

|

||

| m |  |

|

|||

| n |   |

|

|

|

|

| p |   |

|

|

|

|

| s |   |

|

|||

| t |   |

|

|

|

|

| t’ |  |

||||

| tz /ts/ |

|

|

|

|

|

| tz’ |  |

||||

| w |  |

||||

| x /š/ |

|

|

|

||

| y /j/ |

|

|

|||

| a | e | i | o | u |

An Example of Maya Writing

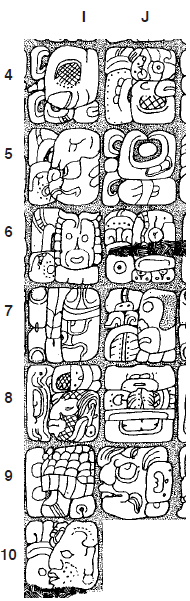

Here is an example of Maya writing from the Tomb of Kʼinich Janaabʼ Pakal.

| Row | Glyphs | Reading | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | J | I | J | |

| 4 | ya k’a wa | ʔu(?) K’UH hu lu | yak’aw | ʔuk’uhul |

| 5 | PIK | 1-WINAAK-ki | pik | juʔn winaak |

| 6 | pi xo ma | ʔu SAK hu na la | pixoʔm | ʔusak hunal |

| 7 | ʔu-ha | YAX K’AHK’ K’UH? | ʔuʔh | Yax K’ahk’ K’uh? |

| 8 | ʔu tu pa | K’UH? ? | ʔutuʔp | k’uh(ul)? ...l |

| 9 | ʔu KOʔHAW wa | ?[CHAAK] ...m | ʔukoʔhaw | Chaahk (‘GI’) |

| 10 | SAK BALUʔN | – | Sak Baluʔn | – |

Text: Yak’aw ʔuk’uhul pik juʔn winaak pixoʔm ʔusak hunal ʔuʔh Yax K’ahk’ K’uh(?) ʔutuʔp k’uh(ul)? ...l ʔukoʔhaw Chaahk (‘GI’) Sak Baluʔn. Translation: «He gave the god clothing, [which included] twenty-nine headgears, a white ribbon, a necklace, the First Fire God’s earrings, and the God’s quadrilateral badge helmet, to Chaahk Sak-Balun».

Bringing Maya Script Back

Recently, there has been more interest in using the Maya script again. Many old works have been written in the script, and new ones have been created. For example, the Popol Vuh, a religious book of the Kʼicheʼ, was written in the script in 2018.

Another example is a modern stele (carved stone) placed at Iximche in 2012. It tells the full history of the site using Maya glyphs. Modern poems, like "Cigarra" by Martín Gómez Ramírez, have also been written entirely in the script.

Images for kids

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |