Egyptian hieroglyphs facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Egyptian hieroglyphs |

|

|---|---|

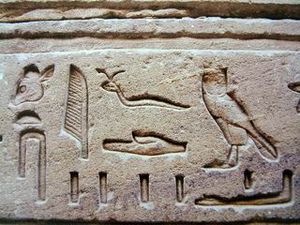

Hieroglyphs from the tomb of Seti I (KV17), 13th century BC

|

|

| Type | Logographic |

| Spoken languages | Egyptian language |

| Time period | c. 3250 BC – c. 400 AD |

| Parent systems |

(Proto-writing)

|

| Child systems |

|

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | |

Egyptian hieroglyphs were a special writing system used in Ancient Egypt. They were like a mix of pictures, symbols, and sounds. Imagine writing with tiny drawings! There were over 100 different characters.

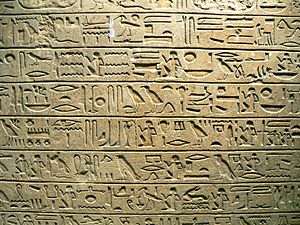

Ancient Egyptians used hieroglyphs for important things. You can see them carved on temple walls and monuments. They also had simpler versions called hieratic and demotic scripts. These were used for writing on papyrus (an early form of paper).

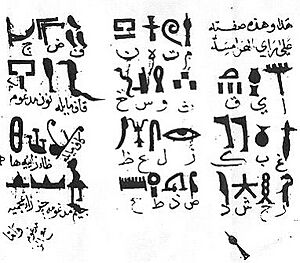

Did you know that Egyptian hieroglyphs are the great-grandparents of many alphabets we use today? The Phoenician alphabet came from them. Then, the Greek and Aramaic alphabets came from Phoenician. Finally, our own Latin alphabet (which English uses) and the Cyrillic script (used in Russian) came from Greek. The Arabic and Brahmic scripts (used in India) came from Aramaic. So, hieroglyphs are super important in the history of writing!

Hieroglyphs started around 3300 BC. The first full sentence written in Egyptian hieroglyphs was found from about 2800 BC. This writing system was used for thousands of years. It was used during the Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom. It even continued into the Ptolemaic and Roman periods, until about 400 AD.

Sadly, by the 5th century AD, people forgot how to read and write hieroglyphs. It was a lost language for over 1,400 years! Many people tried to figure them out, but they couldn't. Then, in the 1820s, a smart French scholar named Jean-François Champollion finally cracked the code. He did it with the help of the famous Rosetta Stone.

Contents

What Does "Hieroglyph" Mean?

The word hieroglyph comes from ancient Greek words. Hieros means 'sacred' or 'holy'. Glypho means 'to carve' or 'to engrave'. So, hieroglyph means "sacred carving."

The Egyptians themselves called their writing mdw.w-nṯr. This means "god's words." They believed their writing was a gift from the gods.

How Hieroglyphs Began

Early Signs and Symbols

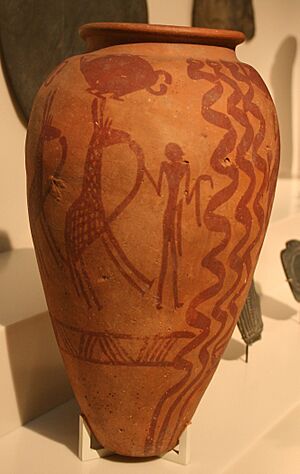

Hieroglyphs might have grown out of early Egyptian art. For example, some symbols on pottery from around 4000 BC look a bit like hieroglyphs.

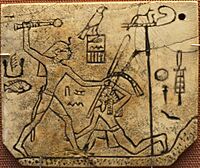

Very early writing systems appeared in Egypt around 3400 BC. These include clay labels found at Abydos. Another famous early example is the Narmer Palette, from about 3100 BC.

The first complete sentence written in hieroglyphs was found in a tomb from the Second Dynasty (around 2800 BC). About 800 hieroglyphs were known during the Old Kingdom, Middle Kingdom, and New Kingdom. By the time of the Greeks and Romans, there were over 5,000!

For a long time, people wondered if Egyptians invented hieroglyphs on their own. Or did they get the idea from another ancient culture, like Sumer in Mesopotamia? Today, many experts believe that writing developed independently in Egypt. The earliest Egyptian symbols are very old, challenging the idea that Mesopotamia was first.

Also, the pictures used in hieroglyphs are all Egyptian. They show plants, animals, and scenes from Egypt's own land. So, even if the idea of writing came from somewhere else, the look of hieroglyphs is totally Egyptian.

-

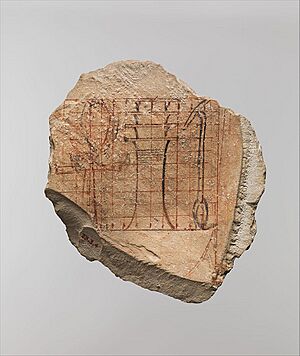

Labels with early writing from the tomb of Menes (3200–3000 BCE)

-

An ivory label with King Den’s name on it, around 2985 BCE

How Hieroglyphs Worked

Egyptian hieroglyphs are a clever system. They use three main types of signs:

- Phonetic glyphs: These are signs that represent sounds, like letters in our alphabet. Some signs stood for one sound, others for two or three sounds.

- Logograms: These are signs that represent a whole word or idea. For example, a picture of a sun could mean "sun."

- Determinatives: These signs were not spoken. They were placed at the end of a word to help explain its meaning. Imagine if you had a picture of a walking person after the word "run" to show it's about movement.

Most hieroglyphic signs are pictures. They look like real things, even if they are simplified. But the same picture could mean different things depending on how it was used. For example, a picture of a duck might mean "duck" (a logogram). Or it might just represent the sounds in the word "duck" (a phonogram).

The Egyptians didn't usually write down vowels (like A, E, I, O, U). This is similar to how some modern languages like Arabic are written. When we read hieroglyphs today, we often add an "e" sound between consonants to make them easier to say. For example, the word for "good" was nfr, but we often say nefer.

The End of Hieroglyphs and Their Rediscovery

Later Egyptian Scripts

As writing became more common, simpler forms of hieroglyphs appeared. These were the hieratic (used by priests) and demotic (used by everyday people) scripts. They were faster to write and better for papyrus. But hieroglyphs didn't disappear! They were still used for important carvings on temples and monuments.

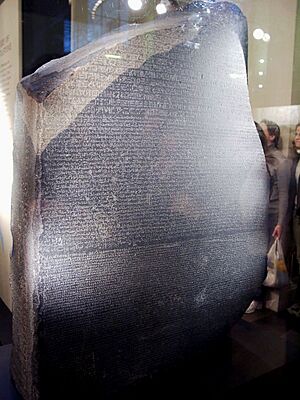

A great example is the Rosetta Stone. It has the same message written three ways: in hieroglyphs, in demotic, and in ancient Greek. This stone was key to understanding hieroglyphs again.

The Last Hieroglyphs

Hieroglyphs continued to be used even when Egypt was ruled by Persians, Greeks, and Romans. Some people think hieroglyphs became a way for Egyptians to show their identity. They wanted to stand out from their foreign rulers.

By the 4th century AD, very few Egyptians could read hieroglyphs. The last known hieroglyphic inscription was made in 394 AD. This was after the Roman Emperor Theodosius I closed all non-Christian temples. After that, the knowledge of hieroglyphs was lost for a very long time.

Cracking the Code: Deciphering Hieroglyphs

For over a thousand years, no one could understand Egyptian hieroglyphs. People tried, but they made a big mistake. They thought hieroglyphs were only pictures that represented ideas, not sounds. So, they couldn't figure out how to read them.

The big breakthrough came in 1799. Napoleon's soldiers found the Rosetta Stone in Egypt. This stone had the same text written in three different scripts: hieroglyphs, demotic, and ancient Greek. Since scholars could read Greek, they now had a way to compare the texts!

In the early 1800s, many smart people studied the Rosetta Stone. Finally, Jean-François Champollion made the complete decipherment in the 1820s. He realized that hieroglyphs were a mix of things: pictures, symbols, and sounds, all used together. This was the key to understanding ancient Egypt's written history!

How Hieroglyphs Were Written

Hieroglyphs are always pictures. They might be simple or detailed, but you can usually tell what they are. A single sign could be read in different ways:

- As a phonogram: This means it represents a sound, like a letter. For example, a picture of a pintail duck was read as sꜣ. This came from the main sounds in the Egyptian word for that duck.

- As a logogram: This means it represents a whole word. The duck picture could mean "duck."

- As a determinative: This sign wasn't spoken. It was added to the end of a word to help clarify its meaning. For example, if you had the sounds sꜣ, a duck determinative would tell you it means "duck." But if you had sꜣ followed by a picture of a child, it would mean "son."

There were 24 single-sound signs, which are like a hieroglyphic alphabet. Egyptian hieroglyphs usually didn't write vowels, just consonants.

Hieroglyphs were written in rows or columns. They could be read from left to right, or from right to left. How do you know which way to read? Look at the people or animals in the pictures! They almost always face the direction you should start reading from. For example, if they face left, you read from left to right.

Unlike our writing, ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs didn't use spaces between words or punctuation marks. But some hieroglyphs often appeared at the end of words, which helped readers know where one word ended and the next began.

See also

In Spanish: Jeroglíficos egipcios para niños

In Spanish: Jeroglíficos egipcios para niños

- List of Egyptian hieroglyphs

- Gardiner's sign list

- Egyptian numerals

- Egyptian language

- Proto-Sinaitic script

- Manuel de Codage

- Champollion Museum

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |