Jean-François Champollion facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jean-François Champollion

|

|

|---|---|

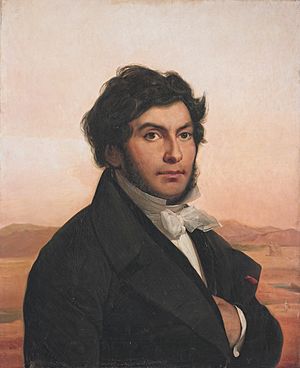

Jean-François Champollion, by Léon Cogniet

|

|

| Born | 23 December 1790 Figeac, France

|

| Died | 4 March 1832 (aged 41) Paris, France

|

| Alma mater | Collège de France Institut national des langues et civilisations orientales |

| Known for | Decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs |

| Spouse(s) | Rosine Blanc |

| Children | 1 |

| Relatives | Jacques Joseph Champollion-Figeac (brother) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Egyptian hieroglyphs |

Jean-François Champollion (born 23 December 1790 – died 4 March 1832) was a French expert in languages and ancient cultures. He is famous for figuring out how to read Egyptian hieroglyphs. This made him a key person in starting the study of Egyptology, which is the study of ancient Egypt. His older brother, Jacques Joseph Champollion-Figeac, who was also a scholar, helped raise him. Jean-François was a child genius when it came to languages. He gave his first public talk on deciphering an ancient Egyptian script called Demotic when he was still a teenager. As a young man, he was well-known among scientists. He could speak Coptic, Ancient Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and Arabic.

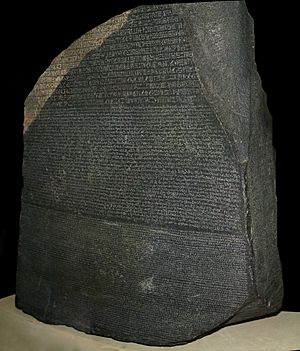

In the early 1800s, French people became very interested in Egypt. This was because of Napoleon's travels there (1798–1801). These trips also brought the famous Rosetta Stone to light. This stone had the same text written in three different scripts. Experts wondered how old Egyptian civilization was. They also debated what hieroglyphs were. Were they just pictures, or did they represent sounds like an alphabet? Many thought hieroglyphs were only for religious use. They believed they were too mysterious to ever be read. Champollion's great achievement was showing that these ideas were wrong. His work made it possible to understand the many stories and facts recorded by the ancient Egyptians.

Champollion lived during a time of big political changes in France. These changes often made his research difficult. During the Napoleonic Wars, he avoided being forced into the army. But his support for Napoleon made him a suspect when the new Royalist government took over. Sometimes, his own bold actions also caused problems for him. Important people like Joseph Fourier and Silvestre de Sacy helped him. Yet, at times, he was kept away from the scientific community.

In 1820, Champollion seriously began working on deciphering hieroglyphs. He soon went beyond the work of the British scientist Thomas Young. Young had made the first steps in understanding the script before 1819. In 1822, Champollion announced his first big discovery. He showed that the Egyptian writing system used a mix of phonetic signs (for sounds) and ideographic signs (for ideas). This was the first time such a writing system had been found. In 1824, he published a book called Précis. In it, he explained in detail how to read hieroglyphs. He showed the values of both their sound and idea signs. In 1829, he traveled to Egypt. There, he read many hieroglyphic texts that no one had studied before. He brought back many new drawings of these inscriptions. Back home, he became a professor of Egyptology. But he only taught a few times. His health, weakened by his trip to Egypt, forced him to stop. He died in Paris in 1832, at 41 years old. His book on Ancient Egyptian grammar was published after he died.

During his life and long after, people argued about how good his decipherment was. Some criticized him for not giving enough credit to Young's early work. They even accused him of copying. Others doubted if his readings were correct. But later discoveries and confirmations by other scholars proved his work was right. His decipherment is now accepted by everyone. It is the basis for all further studies in the field. Because of this, he is known as the "Founder and Father of Egyptology."

Contents

Jean-François Champollion's Life

Early Years and Learning

Jean-François Champollion was born on 23 December 1790. He was the youngest of seven children. Two of his siblings had died earlier. His family was not rich. His father, Jacques Champollion, was a book seller from Valjouffrey. He had settled in the small town of Figeac. Young Champollion was mostly raised by his older brother, Jacques-Joseph.

In March 1801, Jean-François moved to Grenoble. His brother Jacques-Joseph lived there in a small apartment. Jacques-Joseph worked as an assistant in a trading company. But he taught his brother to read and helped with his education. His brother might have also sparked Champollion's interest in Egypt. As a young man, Jacques-Joseph had wanted to join Napoleon's trip to Egypt. He often regretted not being able to go.

Jean-François was often called Champollion le Jeune (the young). This was to tell him apart from his older brother. Later, Jacques-Joseph became more famous. He added his hometown, Figeac, to his name. So he was called Champollion-Figeac. Jacques-Joseph was a hard worker and mostly taught himself. But he did not have Jean-François's amazing talent for languages. Still, he was good at making money. He supported Jean-François for most of his life.

Jacques-Joseph found it hard to educate his brother while working. So, in November 1802, he sent Jean-François to the Abbé Dussert's school. Champollion stayed there until summer 1804. Here, his gift for languages first became clear. He started with Latin and Greek. But he quickly moved on to Hebrew and other Semitic languages like Arabic. It was at this school that he became interested in Ancient Egypt. His teacher and brother, both interested in ancient cultures, likely encouraged him.

At age 11, he met Joseph Fourier. Fourier was the prefect of Grenoble. He had gone with Napoleon Bonaparte on the Egyptian trip. This trip had led to the discovery of the Rosetta Stone. Fourier was a skilled scholar and a famous scientist. Napoleon had asked him to publish the findings of the expedition. This was a huge series of books called Description de l'Égypte. One story says that Fourier invited 11-year-old Champollion to his home. He showed him his collection of Ancient Egyptian items and papers. Champollion was fascinated. When he saw the hieroglyphs and heard they could not be read, he said he would be the one to read them. Whether this story is true or not, Fourier became a very important helper for Champollion. He certainly played a big part in making Champollion interested in Ancient Egypt.

From 1804, Champollion studied at a school in Grenoble. But he disliked its strict rules. He could only study ancient languages one day a week. He begged his brother to move him to a different school. Still, at this school, he began studying Coptic. This language became his main interest for years. It was very important for his work on deciphering hieroglyphs. He got to practice his Coptic when he met Dom Raphaël de Monachis. Monachis was a former Coptic Christian monk. He was also an Arabic translator for Napoleon. He visited Grenoble in 1805. By 1806, Jacques-Joseph was planning to bring his younger brother to Paris for university. Jean-François already had a strong interest in Ancient Egypt. He wrote to his parents in January 1806: "I want to deeply and continuously study this ancient nation. The excitement I feel from studying their monuments, their power and knowledge, fills me with admiration. All of this will grow as I learn more. Of all the people I prefer, I must say none is as important to my heart as the Egyptians." To continue his studies, Champollion wanted to go to Paris. Grenoble offered few chances for such special subjects as ancient languages. So his brother stayed in Paris from August to September that year. He tried to get Jean-François into a special school. Before leaving, on 1 September 1807, Champollion presented his Essay on the Geographical Description of Egypt before the Conquest of Cambyses. He gave it to the Academy of Grenoble. Its members were so impressed that they accepted him into the Academy six months later.

From 1807 to 1809, Champollion studied in Paris. His teachers included Silvestre de Sacy, who was the first Frenchman to try to read the Rosetta Stone. He also studied with Louis-Mathieu Langlès and Raphaël de Monachis, who was now in Paris. Here, he became even better at Arabic and Persian. He also improved the other languages he knew. He was so focused on his studies that he started dressing in Arab clothes. He called himself Al Seghir, which is Arabic for the young. He spent his time between the College of France, the Special School of Oriental Languages, and the National Library. His brother was a librarian there. He also worked at the Commission of Egypt. This group was in charge of publishing the findings from the Egyptian trip. In 1808, he first started studying the Rosetta Stone. He worked from a copy made by the Abbé de Tersan. Working alone, he confirmed some of the Demotic readings made by Johan David Åkerblad in 1802. He finally matched fifteen Demotic signs on the Rosetta Stone to their Coptic equivalents.

In 1810, he went back to Grenoble. He became a joint professor of Ancient History at the newly reopened Grenoble University. His pay as an assistant professor was 750 francs. This was a quarter of what full professors earned.

He was never well-off and always struggled to make enough money. He also had poor health since he was young. His health first got worse during his time in Paris. The damp weather and unhealthy conditions there did not suit him.

Political Challenges

During the Napoleonic Wars, Champollion was a young single man. This meant he could be forced into the army. This would have been very dangerous, as many soldiers died in Napoleon's armies. With help from his brother and Joseph Fourier, he avoided being drafted. He argued that his work on deciphering Egyptian writing was too important to stop. At first, he was unsure about Napoleon's government. But after Napoleon fell in 1813, and Louis XVIII became king, Champollion saw Napoleon's rule as the better choice. He secretly wrote and shared songs that made fun of the king's government. These songs became very popular in Grenoble. In 1815, Napoleon escaped from his exile. He landed in France and marched to Grenoble. People welcomed him as a hero. He met Champollion there. Napoleon remembered Champollion's requests to avoid the army. He asked how his important work was going. Champollion replied that he had just finished his Coptic grammar and dictionary. Napoleon asked him to send the books to Paris to be published. His brother Jacques also supported Napoleon. This put both brothers in danger when Napoleon was finally defeated. Grenoble was the last city to fight against the king's army. Even though they were watched by the Royalists, the Champollion brothers helped a Napoleonic general. This general, Drouet d'Erlon, was sentenced to death. They gave him shelter and helped him escape. The brothers were then sent away to live in Figeac. Champollion lost his university job in Grenoble, and the department was closed.

Under the new Royalist government, the Champollion brothers worked hard to set up Lancaster schools. They wanted to provide education for everyone. This was seen as a revolutionary idea by the Ultra-royalists. They did not believe that lower classes should be educated. In 1821, Champollion even led a small uprising. He and a group from Grenoble stormed a fort. They raised the French flag instead of the king's flag. He was accused of serious actions and went into hiding. But he was later pardoned.

Family Life

In 1813, Champollion met Rosine Blanc (1794–1871). He married her in 1818, after being engaged for four years. They had one daughter, Zoraïde Chéronnet-Champollion (1824–1889). Rosine came from a wealthy family of glove makers in Grenoble. At first, her father did not approve of the marriage. Champollion was only an assistant professor. But as his reputation grew, her father finally agreed. Jacques-Joseph, his brother, was also against the marriage at first. He thought Rosine was not smart enough. He did not go to the wedding. But later, he grew to like his sister-in-law. Champollion loved his family, especially his daughter. But he was often away for months or even years. He traveled to Paris, Italy, and Egypt. His family stayed in Vif, near Grenoble, at his brother's home.

Deciphering Egyptian Hieroglyphs

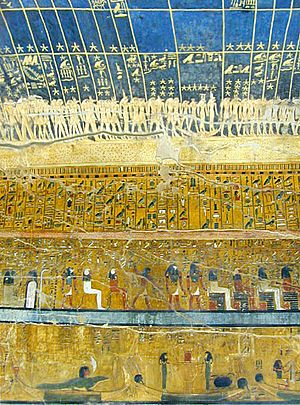

Scholars had known about Egyptian hieroglyphs for centuries. But few had tried to understand them. Many believed the symbols were just pictures, not representing a spoken language. For example, Athanasius Kircher said hieroglyphs "cannot be translated by words." He thought they were only expressed by "marks, characters and figures." This meant he believed they could never be deciphered. Others thought hieroglyphs were only used for religious purposes. They believed they represented secret ideas that were now lost. But Kircher was the first to suggest that modern Coptic was a simpler form of the ancient Egyptian language. He also correctly guessed the sound value of one hieroglyph, the one for mu, the Coptic word for water. When interest in Egypt grew in France, scholars looked at hieroglyphs again. But they still did not know if the script used sounds or ideas. They also did not know if the texts were about everyday life or sacred mysteries. Early work was mostly guesswork. There was no way to check if their ideas were right. The first real steps forward were Joseph de Guignes' discovery that oval shapes (cartouches) held the names of rulers. Also, George Zoëga collected many hieroglyphs. He found that the reading direction depended on which way the symbols faced.

Early Studies and Discoveries

Champollion became interested in Egyptian history and hieroglyphs at a young age. At sixteen, he gave a talk to the Grenoble Academy. He argued that the language of ancient Egypt was closely related to Coptic. This idea was very important for being able to read the texts. History has proven that his idea about Coptic and Ancient Egyptian was correct. This allowed him to suggest that the Demotic script represented the Coptic language.

In 1808, Champollion was worried. French archaeologist Alexandre Lenoir published the first of his books on hieroglyphs. Champollion feared his own work was already behind. But he was relieved to find that Lenoir still thought hieroglyphs were mystic symbols. Lenoir did not see them as a writing system for language. This experience made Champollion even more determined to be the first to decipher the language. He focused even more on studying Coptic. In 1809, he wrote to his brother: "I give myself up entirely to Coptic... I wish to know Egyptian like my French. This is because my great work on the Egyptian papyri will be based on that language." That same year, he got his first academic job. He became a professor of history and politics at the University of Grenoble.

In 1811, Champollion faced a problem. Étienne Marc Quatremère, another student of Silvestre de Sacy, published his own work on Egypt. Champollion felt forced to publish the "Introduction" to his ongoing work. This work was called L'Egypte sous les pharaons (1814). Because the topics were similar, and Champollion's work came out later, people accused him of copying Quatremère. Even Silvestre de Sacy, who had taught both of them, thought it was possible. This upset Champollion greatly.

Competing with Thomas Young

British scientist Thomas Young was one of the first to try to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs. He built on the work of Swedish diplomat Johan David Åkerblad. Young and Champollion first learned about each other's work in 1814. Champollion wrote to the Royal Society, where Young was a secretary. He asked for better copies of the Rosetta Stone. Young found this annoying. Champollion seemed to suggest he could quickly read the script if he just had better copies. Young had already spent months working on the Rosetta text without success. In 1815, Young replied no. He said the French copies were as good as the British ones. He added that he was sure "the collective efforts of savants, such as M. Åkerblad and yourself... might have already succeeded in giving a more perfect translation than my own." This was the first Champollion heard of Young's research. He did not like knowing he had a competitor in London.

Young worked on the Rosetta Stone like a math problem. He did not identify the language of the text. For example, he compared how many times a word appeared in the Greek text with the Egyptian text. This helped him find which hieroglyphs spelled "king." But he could not read the word itself. Using Åkerblad's decipherment of the Demotic letters p and t, he realized there were sound elements in the name Ptolemy. He correctly read the signs for p, t,m, i, and s. But he dismissed other signs as "unimportant" and misread others. This was because he lacked a systematic way of working. Young called the Demotic script "enchorial." He disliked Champollion's term "demotic." He thought it was bad form to invent a new name. Young talked with Sacy, who was now Champollion's rival. Sacy told Young not to share his work with Champollion. He called Champollion a trickster. So, for several years, Young kept important texts from Champollion. He shared little of his information.

When Champollion tried to publish his Coptic grammar and dictionary in 1815, Silvestre de Sacy blocked it. De Sacy disliked Champollion personally. He also disliked Champollion's support for Napoleon. During his forced stay in Figeac, Champollion spent his time fixing his grammar book. He also did local archaeological work. For a while, he could not continue his main research.

In 1817, Champollion read a review of his book "Égypte sous les pharaons." An anonymous Englishman wrote it. The review was mostly positive. It encouraged Champollion to go back to his research. Some people think Young wrote the review. Young often published anonymously. But others say it is unlikely, as Young had been very critical of that book elsewhere. Soon, Champollion returned to Grenoble. He looked for a job at the university again. It was reopening its Philosophy and Letters department. He succeeded. He got a job teaching history and geography. He used his time to visit Egyptian collections in Italian museums. Still, most of his time in the following years was spent teaching.

Meanwhile, Young kept working on the Rosetta Stone. In 1819, he published a big article on "Egypt" in the Encyclopædia Britannica. He claimed he had found the main idea behind the script. He had correctly identified only a few sound values for hieroglyphs. But he also made about eighty guesses about how hieroglyphic and Demotic signs matched up. Young also correctly identified several logographs (signs for whole words). He also understood the grammar rule for making words plural. He correctly told the difference between singular, dual, and plural forms of nouns. Young still believed that hieroglyphic, hieratic (cursive hieroglyphs), and a third script he called epistolographic or enchorial, belonged to different time periods. He thought they showed different stages of the script's development, with more phonetic signs appearing later. He did not tell the difference between hieratic and Demotic. He thought they were the same script. Young also correctly identified the hieroglyphic form of the name of Ptolemy V. Åkerblad had only found this name in the Demotic script. Still, Young only assigned the correct sound values to some signs in the name. He incorrectly ignored one hieroglyph, the one for o, as unnecessary. He also gave partly correct values to the signs for m, l, and s. He also read the name of Berenice. But here, he only correctly identified the letter n. Young was also sure that only in later times were some foreign names written entirely with phonetic signs. He believed that native Egyptian names and all older texts were written with idea-based signs. Several scholars have said that Young's real contribution was deciphering the Demotic script. He made the first big steps there. He correctly identified it as having both idea-based and sound-based signs. But for some reason, Young never thought the same might be true for hieroglyphs.

Later, British Egyptologist Sir Peter Le Page Renouf summarized Young's method. He said Young "worked mechanically." He was sometimes right, but often wrong. And no one could tell the difference until the right method was found. Still, at the time, it was clear that Young's work was better than anything Champollion had published on the script.

The Big Breakthrough

Even though he dismissed Young's work before reading it, Champollion got a copy of the Encyclopedia article. He was suffering from poor health. Also, political tricks made it hard for him to keep his job. But the article motivated him to seriously return to studying hieroglyphs. When the Royalist group finally removed him from his professorship, he finally had time to work on it full-time. While waiting for his trial for serious actions, he wrote a short book. It was called De l'écriture hiératique des anciens Égyptiens. In it, he argued that the hieratic script was just a changed form of hieroglyphic writing. Young had already published a similar idea anonymously years earlier. But Champollion, being cut off from academic life, probably had not read it. Champollion also made a big mistake. He claimed that the hieratic script was entirely based on ideas. Champollion was never proud of this work. He reportedly tried to stop it from spreading by buying copies and destroying them.

These mistakes were corrected later that year. Champollion correctly identified the hieratic script as being based on hieroglyphs. But hieratic was used only on papyrus. Hieroglyphs were used on stone. Demotic was used by the common people. Before, people had wondered if the three scripts even represented the same language. Hieroglyphic had been seen as a purely idea-based script. Hieratic and Demotic were thought to be alphabetic. Young, in 1815, was the first to suggest that Demotic was not alphabetic. He thought it was a mix of "imitations of hieroglyphics" and "alphabetic" signs. Champollion, on the other hand, correctly believed the scripts were almost entirely the same. They were essentially different formal versions of the same writing system.

In the same year, he realized that the hieroglyphic script on the Rosetta Stone was a mix of ideograms (idea signs) and phonetic signs (sound signs). This was just as Young had argued for Demotic. He reasoned that if the script was entirely idea-based, the hieroglyphic text would need as many separate signs as there were words in the Greek text. But there were fewer signs. This suggested the script mixed idea-based and sound-based signs. This understanding finally freed him from the idea that the different scripts had to be either fully idea-based or fully sound-based. He saw it was a much more complex mix of sign types. This realization gave him a clear advantage.

Names of Rulers

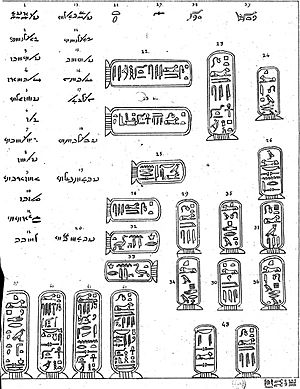

It was known that the names of rulers appeared in cartouches (oval shapes). Using this fact, Champollion focused on reading these names, as Young had tried earlier. Champollion managed to find several sound values for signs. He did this by comparing the Greek and Hieroglyphic versions of the names Ptolemy and Cleopatra. He corrected Young's readings in several places.

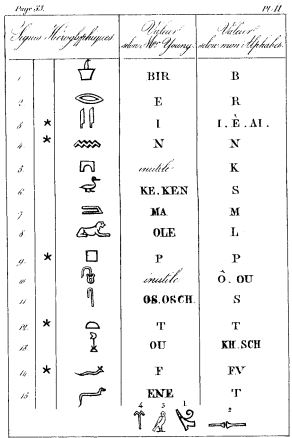

In 1822, Champollion received copies of the text from the recently found Philae obelisk. This allowed him to double-check his readings of the names Ptolemy and Cleopatra from the Rosetta Stone. The name "Cleopatra" had already been found on the Philae obelisk by William John Bankes. Bankes had scribbled the identification in the margin. But he did not actually read the individual hieroglyphs. Young and others later used the fact that Bankes had identified the Cleopatra cartouche. They claimed Champollion had copied his work. It is still unknown if Champollion saw Bankes's note or if he found it himself. In total, using this method, he figured out the sound value of 12 signs (A, AI, E, K, L, M, O, P, R, S, and T). By using these to decipher more sounds, he soon read dozens of other names.

Astronomer Jean-Baptiste Biot published his idea for deciphering the Dendera zodiac. He argued that the small stars next to certain signs referred to star groups. Champollion published a response. He showed that they were actually grammar signs. He called them "signs of the type," which are now called "determinatives." Young had found the first determinative, "divine female." But Champollion now found several others. He presented his progress to the academy. It was well received. Even his former teacher and rival, de Sacy, praised it warmly. This led to them becoming friends again.

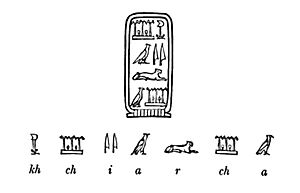

The main breakthrough in his decipherment came when he could also read the verb MIS. This verb was related to birth. He did this by comparing the Coptic verb for birth with the phonetic signs MS. He also looked at mentions of birthday celebrations in the Greek text. It was on 14 September 1822, while comparing his readings to new texts from Abu Simbel, that he made the discovery. He ran down the street to find his brother, yelling "Je tiens mon affaire!" (I've got it!). But he collapsed from the excitement. Champollion then spent the short period from 14 to 22 September writing down his findings.

The name Thutmose had also been identified (but not read) by Young. Young realized the first part of the name was spelled with a picture of an ibis representing Thoth. Champollion was able to read the phonetic spelling of the second part of the word. He checked it against mentions of births in the Rosetta Stone. This finally confirmed to Champollion that both ancient and more recent texts used the same writing system. And it was a system that mixed picture-based and sound-based principles.

The Letter to Dacier

A week later, on 27 September 1822, he published some of his findings. This was in his Lettre à M. Dacier. It was addressed to Bon-Joseph Dacier, secretary of the Paris Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. The handwritten letter was first meant for De Sacy. But Champollion crossed out his former teacher's name. He put Dacier's name instead, as Dacier had always supported him. Champollion read the letter to the assembled Académie. All his main rivals and supporters were there, including Young, who was visiting Paris. This was the first time the two met. The presentation did not go into great detail about the script. In fact, it was surprisingly careful in its suggestions. Even though he must have been sure, Champollion only suggested that the script was phonetic even in the oldest texts. This would mean Egyptians developed writing on their own. The paper still had some confusion about the roles of idea-based and sound-based signs. It still argued that hieratic and Demotic were mainly idea-based.

Scholars have guessed that he simply did not have enough time. He made his breakthrough and then collapsed. So he could not fully include the discovery in his thoughts. But the paper showed many new phonetic readings of rulers' names. It clearly showed he had made a big step in deciphering the phonetic script. And it finally settled the question of the Dendera zodiac's age. He read the cartouche that Young had wrongly read as Arsinoë. Champollion correctly read it as "autocrator" (Emperor in Greek).

The amazed audience, including de Sacy and Young, congratulated him. Young and Champollion got to know each other over the next few days. Champollion shared many of his notes with Young. He invited him to visit his house. The two parted on friendly terms.

Reactions to the Decipherment

At first, Young appreciated Champollion's success. He wrote to a friend: "If he [Champollion] did borrow an English key, the lock was so dreadfully rusty that no common arm would have had strength enough to turn it... You will easily believe that were I ever so much the victim of the bad passions, I should feel nothing but exultation at Mr. Champollion's success."

However, their relationship quickly worsened. Young began to feel he was not getting enough credit for his own "first steps" in decipherment. Also, because of the tension between England and France after the Napoleonic Wars, the English were not eager to accept Champollion's work. When Young later read the published lettre, he was offended. He was mentioned only twice, and one time he was sharply criticized for failing to decipher the name "Berenice." Young was further upset because Champollion never said that Young's work had helped him. He became increasingly angry with Champollion. He shared his feelings with friends, who told him to publish a new response. Later that year, by chance, he got a Greek translation of a well-known Demotic papyrus. He did not share this important finding with Champollion. In an anonymous review of the lettre, Young said that de Sacy discovered hieratic as a form of hieroglyphs. He described Champollion's decipherments as just an extension of Åkerblad and Young's work. Champollion knew Young was the author. He sent him a reply to the review, while pretending the review was anonymous. Also, in his 1823 book, Young complained that "however Mr Champollion may have arrived at his conclusions, I admit them... not by any means as superseding my system, but as fully confirming and extending it."

In France, Champollion's success also created enemies. Edmé-Francois Jomard was a main one. He often spoke badly of Champollion's achievements behind his back. He pointed out that Champollion had never been to Egypt. He suggested that Champollion's lettre was not much progress from Young's work. Jomard had been offended by Champollion's proof that the Dendera zodiac was not very old. Jomard himself had claimed it was 15,000 years old. This finding, however, made many Catholic Church priests happy. They had been upset by claims that Egyptian civilization might be older than their accepted timeline, which said the Earth was only 6,000 years old.

The Précis

Young claimed that the new decipherments only proved his own method. This meant Champollion had to publish more of his findings. He needed to show clearly that his progress was based on a systematic approach that Young's work lacked. He realized he had to make it clear to everyone that his was a complete system of decipherment. Young had only deciphered a few words. Over the next year, he published a series of small books about Egyptian gods. These included some decipherments of their names.

Building on his progress, Champollion now began to study other texts besides the Rosetta Stone. He studied a series of much older inscriptions from Abu Simbel. In 1822, he successfully identified the names of pharaohs Ramesses and Thutmose. These names were written in cartouches in these ancient texts. With help from a new friend, the Duke de Blacas, Champollion finally published the Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens in 1824. King Louis XVIII funded and dedicated the book. In it, he presented the first correct translation of the hieroglyphs. He also provided the key to the Egyptian grammar system.

This book was exactly what Champollion wanted to achieve. The whole argument was a reply to M. le docteur Young. Champollion dismissed Young's translation in his 1819 article as "a guessed translation."

In the introduction, Champollion explained his argument:

- His "alphabet" (meaning his phonetic readings) could be used to read inscriptions from all periods of Egyptian history.

- Finding the phonetic alphabet was the true key to understanding the entire hieroglyphic system.

- Ancient Egyptians used this system in all periods to write the sounds of their spoken language.

- Almost all hieroglyphic texts were made up of the phonetic signs he had discovered.

Champollion never admitted he owed anything to Young's work. However, in 1828, a year before his death, Young was appointed to the French Academy of Sciences. Champollion supported this.

The Précis included over 450 ancient Egyptian words and hieroglyphic groups. It firmly established Champollion as the main person to decipher hieroglyphs. In 1825, his former teacher and enemy Silvestre de Sacy reviewed his work positively. He said it was already "beyond the need for confirmation." In the same year, Henry Salt tested Champollion's decipherment. He successfully used it to read more inscriptions. He published a confirmation of Champollion's system. In it, he also criticized Champollion for not acknowledging his reliance on Young's work.

After working on the Précis, Champollion realized he needed more texts. He also needed better copies of them to make further progress. So he spent the next years visiting collections and monuments in Italy. There, he found that many of the copies he had been working from were wrong. This had made decipherment harder. He made sure to make his own copies of as many texts as possible. During his time in Italy, he met the Pope. The Pope congratulated him for doing a "great service to the Church." The Pope meant that Champollion had provided arguments against those who challenged the Bible's timeline. Champollion felt mixed emotions. But the Pope's support helped him get money for an expedition.

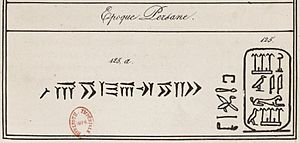

Helping Decipher Cuneiform

The deciphering of the cuneiform script began in 1802. Friedrich Münter realized that repeating groups of characters in Old Persian inscriptions must mean "king." Georg Friedrich Grotefend expanded on this. He realized a king's name is often followed by "great king, king of kings" and the name of the king's father. Through careful thinking, Grotefend figured out the cuneiform characters for Darius, Darius's father Hystaspes, and Darius's son Xerxes. Grotefend's work on Old Persian was special. He did not have comparisons between Old Persian and known languages. This was different from the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs and the Rosetta Stone. He did all his decipherments by comparing the texts with known history. Grotefend presented his ideas in 1802. But the academic community did not accept them.

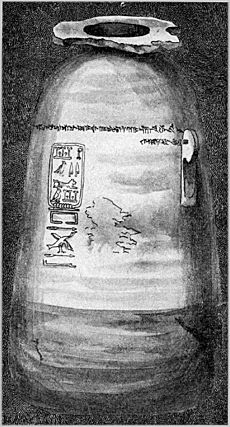

It was only in 1823 that Grotefend's discovery was confirmed. Champollion, who had just deciphered hieroglyphs, had an idea. He tried to read the four-language hieroglyph-cuneiform inscription on a famous alabaster vase. This was the Caylus vase in the Cabinet des Médailles. The Egyptian inscription on the vase turned out to be in the name of King Xerxes I. Antoine-Jean Saint-Martin, an expert in ancient Eastern languages, was with Champollion. He confirmed that the matching words in the cuneiform script meant "king" and "Xerxes." These were the words Grotefend had guessed. This was the first time Grotefend's ideas could be proven right. In short, deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs was key to confirming the first steps of deciphering the cuneiform script.

More progress was made on Grotefend's work. By 1847, most of the symbols were correctly identified. Deciphering the Old Persian Cuneiform script was the start of deciphering all other cuneiform scripts. This happened as more multi-language inscriptions were found. The decipherment of Old Persian was then very important for deciphering Elamite and Babylonian. This was thanks to the three-language Behistun inscription. This eventually led to the decipherment of Akkadian (Babylonian's older form) and then Sumerian. This was helped by finding ancient Akkadian-Sumerian dictionaries.

Proving Old Phonetic Hieroglyphs

Some scholars doubted if phonetic hieroglyphs existed before the Greeks and Romans in Egypt. Champollion had only proven his phonetic system using the names of Greek and Roman rulers found in hieroglyphs. Until he deciphered the Caylus vase, he had not found any foreign names older than Alexander the Great written with alphabetic hieroglyphs. This made people suspect that phonetic hieroglyphs were invented by the Greeks and Romans. It also raised doubts if phonetic hieroglyphs could be used to read the names of ancient Egyptian Pharaohs. For the first time, here was a foreign name ("Xerxes the Great") written phonetically with Egyptian hieroglyphs. This was 150 years before Alexander the Great. This essentially proved Champollion's idea. In his Précis du système hiéroglyphique published in 1824, Champollion wrote about this discovery: "It has thus been proved that Egyptian hieroglyphs included phonetic signs, at least since 460 BC."

Curator at the Louvre Museum

After his big discoveries in 1822, Champollion met Pierre Louis Jean Casimir Duc de Blacas. Blacas was an expert in old things. He became Champollion's supporter and helped him gain the king's favor. Because of this, in 1824, Champollion traveled to Turin. He went to examine a collection of Egyptian items gathered by Bernardino Drovetti. King Charles X had bought this collection. Champollion cataloged it. In Turin and Rome, he realized he needed to see Egyptian monuments firsthand. He began planning a trip to Egypt. He also worked with scholars from Tuscany and Archduke Leopold. In 1824, he became a member of the Royal Institute of the Netherlands.

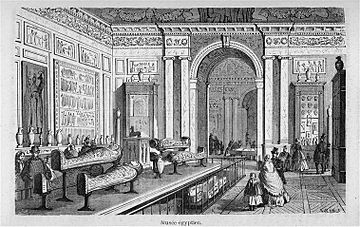

After his successes, and after months of talks by Jacques-Joseph while Champollion was still in Italy, Champollion finally got a new job. He was made curator of the Egyptian collections at the Musée du Louvre. King Charles X issued a decree on 15 May 1826 for this. The two Champollion brothers organized the Egyptian collection. They put it in four rooms on the first floor of the south side of the Cour Carrée. Visitors entered this part of the Louvre through a first room about Egyptian funerals. The second room showed items related to daily life in Ancient Egypt. The third and fourth rooms had more items about death rituals and gods. To help with this big task, Champollion organized the Egyptian collection carefully. He put items into clear groups. He even chose how the display stands and pedestals would look.

Champollion's work at the Louvre, and his and his brother's efforts to get more Egyptian items, greatly changed the museum. The Louvre changed from a place for fine arts to a modern museum. It now had important galleries showing the history of different civilizations.

The Franco-Tuscan Expedition

In 1827, Ippolito Rosellini went to Paris for a year. He had met Champollion in Florence in 1826. He wanted to learn more about Champollion's decipherment method. The two language experts decided to go on a trip to Egypt. They wanted to confirm if the decipherment was correct. Champollion led the mission. Rosellini, his first student and good friend, helped him. This trip was called the Franco-Tuscan Expedition. It was possible because of support from the grand-duke of Tuscany, Leopold II, and Charles X. Champollion and Rosellini were joined by Charles Lenormant, representing the French government. The team also included eleven Frenchmen, like Egyptologist and artist Nestor L'Hote. There were also Italians, including the artist Giuseppe Angelelli.

To prepare for the trip, Champollion wrote to the French Consul General Bernardino Drovetti. He asked for advice on how to get permission from the Egyptian ruler, Muhammad Ali of Egypt. Drovetti had his own business selling ancient Egyptian items. He did not want Champollion interfering. He sent a letter saying the political situation was too unstable for the trip. The letter reached Jacques Joseph Champollion a few weeks before the trip was supposed to start. But he purposely waited to send it to his brother until after the expedition had left.

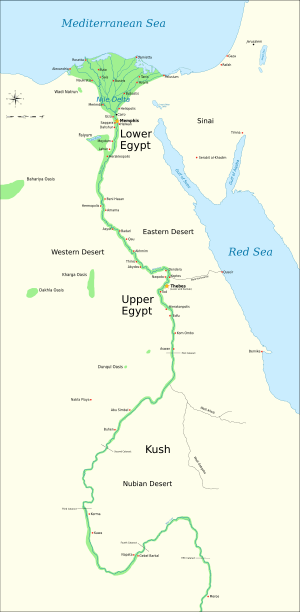

On 21 July 1828, the expedition boarded the ship Eglé in Toulon. They sailed for Egypt and arrived in Alexandria on 18 August. Here, Champollion met Drovetti. Drovetti kept warning about the political situation. But he promised Champollion that the Pasha would give permission for the trip. Champollion, Rosselini, and Lenormant met with the Pasha on 24 August. He immediately gave his permission. However, after more than a week of waiting for the permissions, Champollion suspected Drovetti was working against him. He complained to the French consulate. The complaint worked. Soon, the pasha gave the expedition a large river boat. The expedition bought a small boat for five people. Champollion named them the Isis and the Athyr after Egyptian goddesses. On 19 September, they arrived in Cairo. They stayed there until 1 October. Then they left for the desert sites of Memphis, Saqqara, and Giza.

While looking at texts in the tombs at Saqqara in October, Champollion realized something. The hieroglyphic word for "hour" included a star hieroglyph. This star had no sound function in the word. He wrote in his journal that the star symbol was "the determinative of all divisions of time." Champollion likely created this term while in Egypt. It replaced his earlier phrase "signs of the type." This term had not appeared in the 1828 edition of the Précis. Champollion also saw the sphinx. He regretted that the inscription on its chest was covered by too much sand to remove in a week. Arriving in Dendera on 16 November, Champollion was excited to see the Zodiac he had deciphered in Paris. Here, he realized that the hieroglyph he had read as autocrator was not actually on the monument. This sign had made him think the inscription was recent. It seemed Jomard's copyist had invented it. Champollion still realized the late date was correct, based on other clues. After a day at Dendera, the expedition continued to Thebes.

Champollion was especially impressed by the many important monuments and inscriptions at Thebes. He decided to spend as much time there as possible on the way back north. South of Thebes, the Isis boat leaked and almost sank. They lost many supplies and spent several days fixing the boat. They then continued south to Aswan. The boats had to be left there because they could not pass the first Cataract. They traveled by small boats and camels to Elephantine and Philae. At Philae, Champollion spent several days recovering from a health problem. It was caused by the difficult trip. He also received letters from his wife and brother. Both had been sent many months earlier. Champollion thought Drovetti's bad intentions caused the delay. They arrived at Abu Simbel on 26 November. The site had been visited by Bankes and Belzoni in 1815 and 1817. But the sand they had cleared from the entrance had returned. On 1 January 1829, they reached Wadi Halfa and turned north. That day, Champollion wrote a letter to M. Dacier. He stated: "I am proud now, having followed the course of the Nile from its mouth to the second cataract, to have the right to announce to you that there is nothing to modify in our 'Letter on the Alphabet of the Hieroglyphs.' Our Alphabet is good."

Even though Champollion was upset by the widespread looting of ancient items and destruction of monuments, the expedition also caused some damage. Most notably, while studying the Valley of the Kings, he damaged KV17, the tomb of Seti I. He removed a wall panel measuring 2.26 x 1.05 meters from a corridor. English explorers tried to stop the damage to the tomb. But Champollion insisted he had permission from Muhammad Ali Pasha. Champollion also carved his name into a pillar at Karnak. In a letter to the Pasha, he suggested that tourism, digging for artifacts, and selling them should be strictly controlled. Champollion's ideas may have led to Muhammad Ali's 1835 rule. This rule banned all exports of ancient items. It also ordered the building of a museum to house the ancient artifacts.

On the way back, they stayed again at Thebes from March to September. They made many new drawings and paintings of the monuments there. Here, at the Valley of the Kings, the expedition moved into the tomb of Ramesses IV (of the 20th Dynasty). The air was cooler there. They also found the tomb of Ramesses the Great, but it had been badly looted. It was here that Champollion first heard about Young's efforts to prove himself as the decipherer of hieroglyphs. He also heard about Young's attempts to discredit Champollion's work. He received this news only a few days after Young's death in London.

The expedition arrived back in Cairo in late September 1829. There, the expedition bought 10,000 francs worth of ancient items. This budget was given to them by minister Rochefoucauld. Arriving in Alexandria, they were told the French boat that would take them back was delayed. They had to stay there for two months until December 6th. When they returned to Alexandria, the ruler Muhammad Ali Pasha offered two obelisks to France in 1829. These obelisks stood at the entrance of Luxor Temple. But only one was transported to Paris. It now stands in the Place de la Concorde. Champollion and the Pasha often spoke. At the Pasha's request, Champollion wrote a summary of Egyptian history. Here, Champollion had to challenge the short Biblical timeline. He argued that Egyptian civilization began at least 6000 years before Islam. The two also talked about social changes. Champollion supported educating the lower classes. This was a point on which they disagreed.

Returning to Marseille on the Côte d'Azur, the expedition members had to spend a month in quarantine on the ship. Then they could continue to Paris. The expedition led to a large book published after his death. It was called Monuments de l'Égypte et de la Nubie (1845).

Death and Legacy

After his second trip to Egypt, Champollion was given a special job. He became the professor of Egyptian history and archaeology at the Collège de France. This position was created just for him by a decree from Louis Philippe I on 12 March 1831. He only gave three lectures before his illness forced him to stop teaching. Champollion died in Paris on 4 March 1832, at age 41. He was exhausted from his hard work during and after his trip to Egypt. His body was buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery. On his tomb is a simple obelisk put there by his wife. A stone slab simply says: Here rests Jean-François Champollion, born at Figeac, Department of the Lot, on 23 December 1790, died at Paris on 4 March 1832.

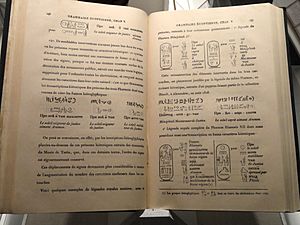

Some of Champollion's works were edited by his brother Jacques and published after his death. His Grammar and Dictionary of Ancient Egyptian was almost finished. It was published in 1838. Before he died, he told his brother: "Hold it carefully, I hope that it will be my calling card for posterity." It contained his full theory and method. This included how he classified signs and deciphered them. It also had grammar rules, like how to change nouns and verbs. But it had some problems. Many readings were still uncertain. Also, Champollion believed hieroglyphs could be read directly in Coptic. But in fact, they represented a much older form of the language, which was different from Coptic in many ways.

Jacques's son, Aimé-Louis (1812–1894), wrote a book about the two brothers. He and his sister Zoë Champollion were both interviewed by Hermine Hartleben. Her major book about Champollion was published in 1906.

Champollion's decipherment remained a topic of debate even after his death. The brothers Alexander and Wilhelm von Humboldt strongly supported his work. So did Silvestre de Sacy. But others, like Gustav Seyffarth, Julius Klaproth, and Edmé-François Jomard, sided with Young. They refused to see Champollion as more than a talented copier of Young, even after his grammar book was published. In England, Sir George Lewis still argued 40 years after the decipherment that it was impossible to read hieroglyphs. This was because the Egyptian language was extinct. In response to Lewis's harsh criticism, Reginald Stuart Poole, an Egyptologist, defended Champollion's method. He called it "the method of interpreting Hieroglyphics originated by Dr. Young and developed by Champollion." Sir Peter Le Page Renouf also defended Champollion's method, though he was less respectful to Young.

Building on Champollion's grammar, his student Karl Richard Lepsius continued to develop the decipherment. Unlike Champollion, Lepsius realized that vowels were not written. Lepsius became the most important supporter of Champollion's work. In 1866, the Decree of Canopus was discovered by Lepsius. It was successfully deciphered using Champollion's method. This cemented his reputation as the true decipherer of hieroglyphs.

Champollion's Impact

Champollion's most direct impact is in the field of Egyptology. He is now widely seen as its founder and father. His decipherment was the result of his amazing talent combined with hard work.

His hometown, Figeac, honors him with La place des Écritures. This is a huge copy of the Rosetta Stone made by American artist Joseph Kosuth (pictured to the right). Also, a museum dedicated to Jean-François Champollion was created in his birthplace in Figeac. It opened on 19 December 1986. After two years of building work, the museum reopened in 2007. Besides Champollion's life and discoveries, the museum also tells the story of writing. The entire front of the building is covered in pictograms from around the world.

In Vif near Grenoble, The Champollion Museum is located at his brother's old home.

Champollion has also been shown in many films and documentaries. For example, Elliot Cowan played him in the 2005 BBC TV show Egypt. His life and how he deciphered hieroglyphics were told by Françoise Fabian and Jean-Hugues Anglade in the 2000 Arte documentary film Champollion: A Scribe for Egypt. In David Baldacci's thriller Simple Genius, a character named "Champ Pollion" was inspired by Champollion.

In Cairo, a street is named after him. It leads to Tahrir Square, where the Egyptian Museum is located.

The Champollion crater on the far side of the Moon is also named after him.

Works by Champollion

- L'Égypte sous les Pharaons, ou recherches sur la géographie, la religion, la langue, les écritures et l'histoire de l'Égypte avant l'invasion de Cambyse. Tome premier: Description géographique. Introduction.. Paris: De Bure. 1814. OCLC 716645794. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k10475309.

- L'Égypte sous les Pharaons, ou recherches sur la géographie, la religion, la langue, les écritures et l'histoire de l'Égypte avant l'invasion de Cambyse. Description géographique. Tome Second.. Paris: De Bure. 1814. OCLC 311538010. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k10412735.image.

- De l'écriture hiératique des anciens Égyptiens. Grenoble: Imprimerie Typographique et Lithographique de Baratier Frères. 1821. OCLC 557937746.

- Lettre à M. Dacier relative à l'alphabet des hiéroglyphes phonétiques employés par les égyptiens pour écrire sur leurs monuments les titres, les noms et les surnoms des souverains grecs et romains. Paris: Firmin Didot Père et Fils. 1822. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k396352/f3.image. See also the wikipedia article Lettre à M. Dacier.

- Panthéon égyptien, collection des personnages mythologiques de l'ancienne Égypte, d'après les monuments (explanatory text to illustrations by Léon-Jean-Joseph Dubois). Paris: Firmin Didot. 1823. OCLC 743026987. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k106204z.image.

- Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens, ou recherches sur les éléments premiers de cette écriture sacrée, sur leurs diverses combinaisons, et sur les rapports de ce systéme avec les autres méthodes graphiques égytpiennes. Paris, Strasbourg, Londres: Treuttel et Würtz. 1824. OCLC 490765498. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k117252f.;

- Lettres à M. le Duc de Blacas d'Aulps relatives au Musée Royal Egyptien de Turin. Paris: Firmin Didot Père et Fils. 1824. OCLC 312365529. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k65247619.texteImage.;

- Notice descriptive des monuments Égyptiens du musée Charles X. Paris: Imprimerie de Crapelet. 1827. OCLC 461098669. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1040365n/f9.image.;

- Lettres écrites d'Égypte et de Nubie. 10764. Project Gutenberg. 1828–1829. OCLC 979571496. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/10764.;

Works Published After His Death

- Monuments de l'Egypte et de la Nubie: d'après les dessins exécutés sur les lieux sous la direction de Champollion le-Jeune, et les descriptions autographes qu'il en a rédigées. Volume 1 & 2. Paris: Typographie de Firmin Didot Frères. 1835–1845. OCLC 603401775. https://archive.org/details/monumentsdelgy12cham.

- Grammaire égyptienne, ou Principes généraux de l'ecriture sacrée égyptienne appliquée a la représentation de la langue parlée. Paris: Typographie de Firmin Didot Frères. 1836. OCLC 25326631. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1047536s. See also the wikipedia article Grammaire égyptienne

- Dictionnaire égyptien en écriture hiéroglyphique. Paris: Firmin Didot Frères. 1841. OCLC 943840005. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k106209v.image.

See also

In Spanish: Jean-François Champollion para niños

In Spanish: Jean-François Champollion para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |