Far side of the Moon facts for kids

The far side of the Moon is the part of the Moon that always faces away from Earth. It's the opposite of the near side. This happens because of something called synchronous rotation, where the Moon's spin matches its orbit around Earth.

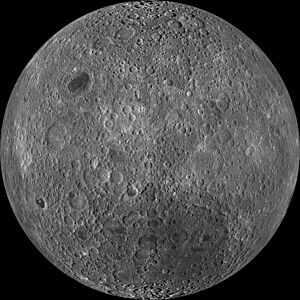

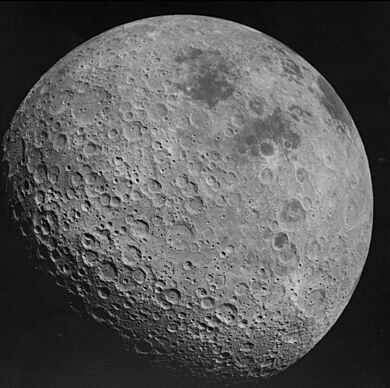

Compared to the near side, the far side looks very rough. It has many impact craters and only a few flat, dark areas called lunar maria (which means "seas"). This makes it look more like other rocky places in our Solar System, such as Mercury or Callisto. It's also home to one of the biggest craters in the Solar System, called the South Pole–Aitken basin.

Sometimes, people call it the "Dark side of the Moon." But "dark" here means "unknown," not that it's always in shadow. Every part of the Moon gets about two weeks of sunlight, while the opposite side has night.

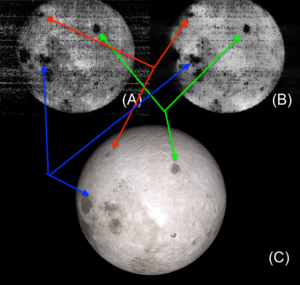

We can sometimes see about 18 percent of the far side from Earth. This is due to the Moon's slight wobbles, called libration. The rest, 82 percent, was a mystery until 1959. That's when the Soviet Luna 3 space probe took the first pictures of it. In 1968, the Apollo 8 astronauts were the first humans to see the far side with their own eyes.

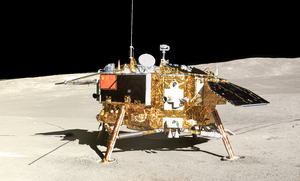

For a long time, all soft landings on the Moon happened on the near side. But on January 3, 2019, China's Chang'e 4 spacecraft made history. It was the first to land successfully on the far side. More recently, the Chang'e 6 mission launched in May 2024. It landed in the Apollo basin to collect the first rock samples from the far side.

Scientists have also thought about putting a large radio telescope on the far side. The Moon would act like a shield, blocking out radio signals from Earth. This would help astronomers listen to space without interference.

Contents

What is the Far Side of the Moon?

The Earth's gravity has slowed down the Moon's spin over a very long time. Now, the Moon spins at the same speed it orbits Earth. This means the same side always faces us. This effect is called tidal locking. The side we almost never see is called the "far side of the Moon."

However, the Moon does wobble a little as it orbits. This wobble is called libration. Because of libration, we can actually see about 59 percent of the Moon's surface over time. But the parts of the far side we see are always at a very low angle. This makes it hard to study them well.

Many people mistakenly think the Moon doesn't spin at all. If it didn't spin, we would see all of its surface as it orbits Earth. Instead, its spin period matches its orbit period. This means its "day" and its "year" are the same length, about 29.5 Earth days.

The term "dark side of the Moon" is often misunderstood. It doesn't mean "dark" as in no light. It means "dark" as in unknown or unseen. Before spacecraft went around the Moon, this area had never been viewed by humans. In reality, both the near and far sides get almost the same amount of sunlight.

The near side also gets extra light reflected from Earth. This is called earthshine. During a full Moon (as seen from Earth), the entire far side of the Moon is dark.

The word "dark" also refers to communication problems. When spacecraft are on the far side, the Moon blocks their radio signals to Earth. This means they can't talk to us directly.

How is the Far Side Different?

The two halves of the Moon look very different. The near side has many large, flat, dark plains called maria. Early astronomers thought these were seas of lunar water.

The far side, however, looks heavily scarred. It has many craters and very few maria. Only about 1% of the far side is covered by maria. On the near side, about 31.2% is covered.

Scientists think this difference might be because of heat-producing elements. The near side seems to have more of these elements. This could have caused more lava to flow and fill in craters on the near side. Even the huge South Pole–Aitken basin on the far side, which has low elevations and thin crust, didn't have as much volcanic activity as the near side's Oceanus Procellarum.

The far side also has more visible craters. This is not because Earth protects the near side from impacts. NASA says Earth only blocks a tiny part of the sky from the Moon. So, both sides likely get hit by the same number of objects. But on the near side, lava flows covered up many of the craters, making them less visible.

Newer research suggests that heat from Earth, when the Moon was forming, played a role. The Moon's outer layer, called the lunar crust, formed from certain elements. The far side cooled faster and formed a thicker crust. When meteoroids hit the thinner crust on the near side, they could break through. This released basaltic lava that created the maria. But on the far side, the thicker crust made this much less likely.

The far side also has much bigger changes in its landscape. The Moon's highest and lowest points are both found on the far side. Its tallest mountains, measured from their base, are also there.

Exploring the Far Side

First Views

Before the late 1950s, we knew very little about the far side of the Moon. The Moon's wobbles (librations) allowed us to peek at features near the edge. But these views were from a very low angle, making it hard to tell what they were. About 82% of the far side remained a complete mystery. People had many ideas about what it might look like.

For example, the Mare Orientale is a huge impact basin almost 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) wide. Even though it's so big, it wasn't properly named until 1906. Its true nature was only understood in the 1960s.

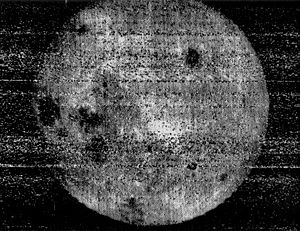

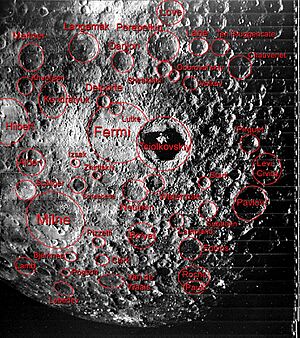

Before space travel, astronomers thought the far side would look much like the near side. But on October 7, 1959, the Soviet probe Luna 3 changed everything. It took the first photos of the far side. Eighteen of these photos were clear enough to show about one-third of the unseen surface. The Soviet Academy of Sciences published the first atlas of the far side in 1960. It listed 500 different features.

In 1961, the Soviet Union released the first globe of the Moon that included features from the far side. Then, on July 20, 1965, another Soviet probe, Zond 3, sent back 25 even better pictures. These showed long chains of craters, but surprisingly, no large maria like those on the near side.

Because Soviet probes discovered many of these features, Soviet scientists chose their names. This caused some debate, but the Soviet Academy of Sciences chose many non-Soviet names too, like Jules Verne and Marie Curie. The International Astronomical Union later accepted many of these names.

More Missions and Human Sightings

On April 26, 1962, NASA's Ranger 4 probe was the first spacecraft to hit the far side of the Moon. However, it didn't send back any scientific information before it crashed.

The first detailed maps of the far side came from the American Lunar Orbiter program between 1966 and 1967. The last probe in this series, Lunar Orbiter 5, provided most of the far side images.

Humans first saw the far side directly during the Apollo 8 mission in December 1968. Astronaut William Anders described it as looking like "a sand pile my kids have played in for some time. It's all beat up, no definition, just a lot of bumps and holes."

All 24 astronauts who flew on Apollo missions (Apollo 8, and Apollo 10 through Apollo 17) saw the far side. Spacecraft flying behind the Moon lost radio contact with Earth. They had to wait until they came back into view to send messages. During the Apollo missions, this caused some tense moments for Mission Control.

Geologist-astronaut Harrison Schmitt wanted Apollo 17 to land on the far side. He aimed for the lava-filled Tsiolkovskiy crater. He even suggested launching a special satellite to keep communication with the astronauts. But NASA decided against it due to the extra risks and costs.

Today, the idea of using a satellite to help with far side communication has come true. China launched the Queqiao relay satellite in 2018. This satellite helps the Chang'e 4 lander and Yutu 2 rover talk to Earth. These missions successfully landed on the lunar far side in early 2019.

First Soft Landings

The China National Space Administration's Chang'e 4 made the first-ever soft landing on the lunar far side on January 3, 2019. It then sent out the Yutu-2 lunar rover.

The lander had tools for studying geology and a low-frequency radio spectrograph. The far side of the Moon is a great place for radio astronomy. This is because the Moon blocks radio interference from Earth.

In February 2020, Chinese astronomers shared the first high-resolution image of a lunar ejecta sequence. This means they saw layers of material thrown out by an impact. They also directly studied its inside structure. These findings came from observations by the Lunar Penetrating Radar (LPR) on the Yutu-2 rover.

NASA and the U.S. Department of Energy are developing a mission called Lunar Surface Electromagnetics Experiment (LuSEE-Night). This lander will go to the far side as early as 2026. It will be a robotic observatory designed to measure electromagnetic waves from the early universe.

China launched Chang'e 6 on May 3, 2024. This mission collected the first lunar samples from the Apollo Basin on the far side of the Moon. It also carried a small Chinese rover called Yidong Xiangji. This rover took pictures of the Chang'e 6 lander and studied the lunar surface. The lander, ascender, and rover separated from the orbiter before landing on June 1, 2024. The ascender then launched back into lunar orbit on June 3, 2024, carrying the collected samples. It will then transfer the samples to a return capsule, which will land in Inner Mongolia in June 2024. This will complete China's far side sample return mission.

Why is the Far Side Important?

Because the far side of the Moon is protected from radio signals from Earth, it's a great spot for radio telescopes. Small, bowl-shaped craters could be natural places for telescopes, like the Arecibo telescope in Puerto Rico. For much bigger telescopes, the Daedalus crater is 100 kilometers (62 miles) wide. Its 3-kilometer (1.9-mile) high rim would help block stray signals from satellites. The Saha crater is another good spot.

However, there are challenges to putting telescopes there. The fine lunar dust can get everywhere. The materials used for the radio dishes need protection from solar flares. Also, the area around the telescopes must be kept free from other radio sources.

The L2 Lagrange point in the Earth–Moon system is about 62,800 kilometers (39,000 miles) above the far side. This spot has also been suggested for a future radio telescope.

One NASA mission being studied would send a lander to the South Pole–Aitken basin to collect samples. This basin is a huge impact site, almost 2,400 kilometers (1,500 miles) across. The impact was so strong that it dug deep into the Moon's surface. Samples from this spot could tell us a lot about what's inside the Moon.

The far side's maria are thought to have the most helium-3 on the Moon's surface. This isotope is rare on Earth. But it could be a very good fuel for fusion reactors. People who want to build a Moon base see this as a reason to set up a base there.

Famous Features on the Far Side

- Aitken (crater)

- Amici (crater)

- Anuchin (crater)

- Apollo (crater)

- Avogadro (crater)

- Bel'kovich (crater)

- Belopol'skiy (crater)

- Bergstrand (crater)

- Berkner (crater)

- Birkhoff (crater)

- Bjerknes (lunar crater)

- Bok (lunar crater)

- Campbell (lunar crater)

- Cantor (crater)

- Carnot (crater)

- Cassegrain (crater)

- Chandler (crater)

- Chappell (crater)

- Chernyshev (crater)

- Comrie (crater)

- Coulomb-Sarton Basin

- Crookes (crater)

- d'Alembert (crater)

- Daedalus (crater)

- Davisson (crater)

- Delporte (crater)

- Dyson (crater)

- Ellerman (crater)

- Emden (crater)

- Esnault-Pelterie (crater)

- Finsen (crater)

- Fleming (crater)

- Fowler (crater)

- Fridman (crater)

- Gerasimovich (crater)

- Gullstrand (crater)

- Hayn (crater)

- Hegu (crater)

- Hertzsprung (crater)

- H. G. Wells (crater)

- Hippocrates (lunar crater)

- Houzeau (crater)

- Icarus (crater)

- Ioffe (crater)

- Izsak (crater)

- Jenner (crater)

- Kamerlingh Onnes (crater)

- Kirkwood (crater)

- Klute (crater)

- Kolhörster (crater)

- Komarov (crater)

- Korolev (lunar crater)

- Kovalevskaya (crater)

- Kugler (crater)

- Kulik (crater)

- Lamb (crater)

- Lacus Luxuriae

- Lacus Oblivionis

- Lander (crater)

- Langevin (crater)

- Lebedev (crater)

- Leibnitz (crater)

- Lucretius (crater)

- Lunar south pole

- Maksutov (crater)

- McKellar (crater)

- Mare Australe

- Mare Frigoris

- Mare Humboldtianum

- Mare Ingenii

- Mare Moscoviense

- Mare Orientale

- Mendeleev (crater)

- Michelson (crater)

- Montes Cordillera

- Montes Rook

- Mons Tai

- Nicholson (lunar crater)

- Nishina (crater)

- Ohm (crater)

- Oppenheimer (crater)

- Oresme (crater)

- Pannekoek (crater)

- Paraskevopoulos (crater)

- Parenago (crater)

- Patsaev (crater)

- Perrine (crater)

- Pettit (lunar crater)

- Pirquet (crater)

- Pogson (crater)

- Priestley (lunar crater)

- Quetelet (crater)

- Rowland (crater)

- Sarton (crater)

- Schlesinger (crater)

- Shaler (crater)

- Shternberg (crater)

- Shuleykin (crater)

- Sniadecki (crater)

- Sommerfeld (crater)

- South Pole–Aitken basin

- Statio Tianhe

- Stebbins (crater)

- Stoletov (crater)

- Sverdrup (crater)

- Tianjin (crater)

- Tikhov (lunar crater)

- Titov (crater)

- Tsinger (crater)

- Tsiolkovskiy (crater)

- Tyndall (lunar crater)

- Vallis Bouvard

- Vallis Inghirami

- van't Hoff (crater)

- Van de Graaff (crater)

- Van der Waals (crater)

- Vavilov (crater)

- Vertregt (crater)

- Virtanen (crater)

- Volkov (crater)

- Von Kármán (lunar crater)

- Von Zeipel (crater)

- Wan-Hoo (crater)

- Wiener (crater)

- Wright (lunar crater)

- Yamamoto (crater)

- Zhinyu (crater)

See also

In Spanish: Cara oculta de la Luna para niños

In Spanish: Cara oculta de la Luna para niños

- Geology of the Moon

- Giant-impact hypothesis

- Near side of the Moon

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |