Egyptomania facts for kids

Egyptomania is a term for when people became super interested in the culture of ancient Egypt. This big wave of interest started in the 1800s. It was sparked by Napoleon's trip to Egypt in 1798.

Napoleon brought many scientists and experts with him. They carefully studied and wrote about the ancient Egyptian monuments. This was the first time these amazing old sites were so well documented. Because of their work, people all over the world became very curious about ancient Egypt. In 1822, Jean-François Champollion finally figured out how to read ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. He used the Rosetta Stone, which French soldiers found in 1799. This discovery officially began the scientific study of Egyptology.

Contents

Egyptian Culture's Big Impact

The fascination with ancient Egypt showed up everywhere. You could see it in books, buildings, art, movies, and even fashion. Not many people could travel to Egypt back then. So, they learned about Egyptian culture mostly through books, art, and architecture. Some very important works included Vivant Denon's Voyage dans la Basse et la Haute Egypt and Giuseppe Verdi's opera Aida.

Egyptian images and symbols were also used for fun things. They appeared on dessert plates, furniture, and decorations. You could even find them in advertisements and on souvenirs. People threw parties with Egyptian themes and wore special costumes. Even today, this interest in Egypt is still strong. Many museums around the world have exhibitions about Egyptian culture. These shows prove that people are still very interested in ancient Egypt. A famous exhibition was "Egyptomania: Egypt in Western Art, 1730-1930." It traveled to Paris, Ottawa, and Vienna in the 1990s.

People in America were especially interested in Egyptian culture. They used what they learned about ancient Egypt in their own discussions. These talks were often about national identity and important social issues. Some parts of Egyptian culture became very meaningful symbols. For example, the mummy became a symbol of life after death. People even held "mummy unwrapping parties" because they were so excited about Egyptian myths!

Other symbols that captured Western imaginations included Cleopatra, hieroglyphic writing, and pyramids. Pyramids were often seen as mysterious mazes. Famous writers like Edgar Allan Poe and Louisa May Alcott wrote stories using these Egyptian ideas. Poe's "Some Words With a Mummy" and Alcott's "Lost in a Pyramid, or The Mummy's Curse" are good examples.

Egyptian Style in Buildings

The influence of ancient Egyptian culture on buildings is called the Egyptian Revival. This style was a big part of neoclassicism in the United States. Builders used well-known Egyptian images, shapes, and symbols in their designs. You can see this influence clearly in the architecture of old cemeteries and prisons.

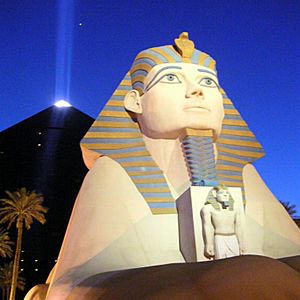

Egyptian Revival symbols were very popular for cemetery entrances and tombstones. They were also used for public memorials in the 1800s and early 1900s. Pyramid-shaped tombs, flat-roofed buildings called mastabas, lotus columns, obelisks, and sphinxes were common. For example, the entrance to Mount Auburn Cemetery in Boston was built in the Egyptian Revival style. The Grove Street Cemetery in New Haven, Connecticut, also shows this influence.

Other examples include the Gold Pyramid House in Illinois. The famous Obelisk (Washington Monument) in Washington, D.C., is also inspired by ancient Egyptian obelisks. Movies like The Mummy (1999) and its sequels show that ancient Egypt is still a popular topic. People are still fascinated by its secrets.

The interest in Egypt didn't start with Napoleon. Ancient Greeks and Romans were also curious about Egyptian culture. They wrote about it in texts like Herodotus' Histories. When Egyptomania reached Rome after Emperor Augustus conquered Egypt in 31 BC, it led to similar architecture. For instance, a high official named Caius Cestius built his tomb like a pyramid. Emperor Hadrian even had his deceased friend honored as Osiris, the Egyptian god of the afterlife.

Egypt and Identity

Egypt holds a special place in history and geography. It's not easily placed in just Africa or Asia, or only in the East or West. Because of this, it seems like Egypt is "everyone's past." The idea of Egypt has been important in shaping national identity in the Western world. This is especially true in the United States. In the 1800s, America was figuring out its own identity. At the same time, there was growing conflict over slavery. These two things were closely linked.

Different groups of people in the United States used Egypt to help define themselves. For example, some scientists in the 1800s studied ancient Egyptians. They used their findings to support ideas about different human groups. These ideas were later proven wrong by science.

Egypt and African American Identity

Many African American thinkers in the 1800s said that ancient Egyptians were Black Africans. This idea helped provide a long and noble history for Black people. It challenged the negative images spread by racist ideas at the time. Important figures like David Walker, James McCune Smith, Frederick Douglass, and W. E. B. Du Bois contributed to this discussion.

African Americans often connected with the story of the enslaved Hebrews in the Bible. They used the biblical Exodus story to express their desire for freedom. The famous spiritual song "Go down, Moses" still shows this connection. David Walker's Appeal (1829) linked this story of freedom to the idea that the pharaohs were also Black.

Later, W. E. B. Du Bois developed the idea of "double consciousness" for Africans in the Diaspora. This meant the descendants of enslaved people in the United States. This concept influenced the Black nationalist movements of the 1900s. It also shaped groups like the "Hotep" community of Black Americans today.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Egiptomanía para niños

In Spanish: Egiptomanía para niños