Hadrian facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Hadrian |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

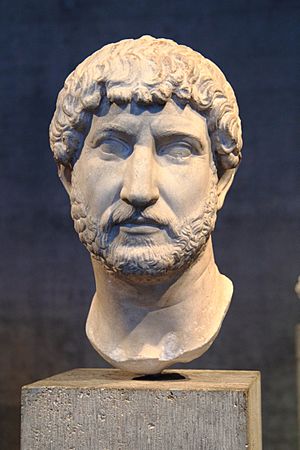

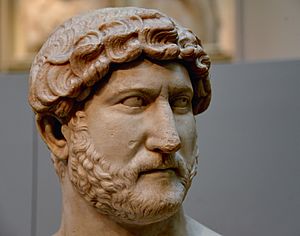

Bust of Hadrian, c. 130

|

|||||

| Roman emperor | |||||

| Reign | 11 August 117 – 10 July 138 | ||||

| Predecessor | Trajan | ||||

| Successor | Antoninus Pius | ||||

| Born | Publius Aelius Hadrianus 24 January 76 Italica, Hispania Baetica, present-day Spain |

||||

| Died | 10 July 138 (aged 62) Baiae, Italia |

||||

| Burial |

|

||||

| Spouse | Vibia Sabina | ||||

| Adoptive children | |||||

|

|||||

| Dynasty | Nerva–Antonine | ||||

| Father |

|

||||

| Mother | Domitia Paulina | ||||

Hadrian (born 24 January 76 – died 10 July 138) was a Roman emperor who ruled from 117 to 138 AD. He was born in Italica, a Roman town in what is now Spain. Hadrian came from a family connected to Emperor Trajan. He married Trajan's grand-niece, Vibia Sabina, early in his career.

When Trajan died, his wife said that he had chosen Hadrian to be the next emperor. The Roman army and Senate agreed to Hadrian becoming emperor. However, some important senators who opposed him were removed from power soon after. Hadrian also decided to change Trajan's plans for expanding the Roman Empire. He gave up some lands in Mesopotamia, Assyria, and Armenia.

Instead, Hadrian focused on making the empire's borders strong and uniting its many different peoples. He is famous for building Hadrian's Wall in Britain. This wall marked the northern edge of the Roman Empire there. Hadrian traveled almost everywhere in the empire. He encouraged soldiers to be ready and disciplined. He also supported many building projects and religious groups. In Rome, he rebuilt the Pantheon and built the huge Temple of Venus and Roma. He loved Greece and wanted to make Athens a cultural center. He ordered many beautiful temples to be built there. Hadrian also put down a major rebellion in Judaea.

Hadrian faced health problems in his later years. He adopted Antoninus Pius in 138 to be his successor. He asked Antoninus to adopt Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus as his own heirs. Hadrian died in 138. Antoninus Pius had him declared a god, even though the Senate was not keen on it. Historians often see Hadrian as a strong and sometimes mysterious leader. He was known for both kindness and strictness.

Contents

Hadrian's Early Life

Hadrian was born on January 24, 76 AD. He was likely born in Italica, a Roman town near modern Seville, Spain. His family name, Hadrianus, came from the town of Hadria in Italy. His family had lived in Hispania for a long time.

Hadrian's father, Publius Aelius Hadrianus Afer, was a senator. His mother, Domitia Paulina, came from a well-known family in Spain. Hadrian had one older sister, Aelia Domitia Paulina. When Hadrian was ten, his parents died. He and his sister were then looked after by Emperor Trajan and Publius Acilius Attianus.

When Hadrian was 14, Trajan brought him to Rome. He made sure Hadrian received a good education, fit for a young Roman noble. Hadrian loved Greek literature and culture. Because of this, he was sometimes called Graeculus, meaning "Greekling."

Becoming a Public Servant

Hadrian started his public career in Rome in a low-level legal job. He then served as a military tribune in the army. He was a tribune three times, which was more than most young nobles. This gave him an advantage in his career.

When Emperor Nerva adopted Trajan as his heir, Hadrian was among those who brought the news to Trajan. After Nerva died in 98, Hadrian quickly went to Trajan. He wanted to be the first to tell him the news.

In 101, Hadrian became a quaestor. This role meant he was a liaison officer between the Emperor and the Senate. He would read the Emperor's messages and speeches to the Senate. He also kept the Senate's records. Hadrian served in Trajan's Dacian Wars. He was a close aide to Trajan during these campaigns. Later, he became governor of Lower Pannonia in 107. His job was to stop the Sarmatians from invading. He defeated an invasion by the Iazyges tribe.

Around 112, Hadrian visited Greece. He became an Athenian citizen and held a high office in Athens for a short time. He then joined Trajan's army for a campaign against Parthia. When the governor of Syria left, Hadrian took his place. He became the commander of the Roman army in the East. Trajan became very ill and died on August 8. Hadrian remained in Syria, in charge of the eastern army.

Hadrian's Family Connections

Around 100 or 101, Hadrian married Vibia Sabina, Trajan's grand-niece. She was about 17 or 18 years old. Their marriage was not a happy one. Trajan's wife, Plotina, may have arranged the marriage. Plotina was a cultured and powerful woman. She shared many of Hadrian's interests. She likely supported Hadrian becoming emperor. This would help her family keep their influence after Trajan's death. Hadrian also had the support of his mother-in-law, Salonia Matidia. She was Trajan's beloved sister's daughter.

Hadrian's personal relationship with Trajan was complicated. Trajan promoted Hadrian's career but was also careful. He did not give Hadrian the highest consulship right away. This showed that Trajan was cautious about naming Hadrian as his heir.

How Hadrian Became Emperor

Not choosing an heir could lead to civil war. But choosing one too early could also cause problems. When Trajan was dying, his wife Plotina was with him. He could have adopted Hadrian as his heir by simply saying so. However, the adoption document was signed by Plotina, not Trajan. It was also dated the day after Trajan died. This caused rumors and doubts about Hadrian's adoption. Hadrian was also still in Syria, which was unusual for an adoption ceremony. Some ancient writers believed the adoption was fake, while others thought it was real. Coins minted early in Hadrian's rule showed him as Trajan's chosen heir.

Hadrian as Emperor (117 AD)

Hadrian wrote to the Senate to tell them he was emperor. He said the army had quickly named him emperor because the state needed a leader. He gave the soldiers a bonus, and the Senate approved. Hadrian also asked for Trajan to be declared a god.

Hadrian stayed in the East for a while. He put down a Jewish revolt that had started under Trajan. He then went to deal with problems along the Danube river. In Rome, Hadrian's former guardian, Attianus, claimed to have found a plot against Hadrian. Four important senators were killed without a public trial. Hadrian said Attianus acted on his own. He rewarded Attianus, then sent him away. Hadrian promised the Senate that he would respect their rights in the future.

The reasons for these deaths are not fully clear. These senators were Trajan's friends and very experienced. They might have wanted to be emperor themselves. They also might have supported Trajan's expansion plans, which Hadrian wanted to change. Hadrian's actions damaged his relationship with the Senate for the rest of his rule.

Hadrian's Travels

British Museum, London.

Hadrian spent more than half of his time as emperor outside Italy. Most emperors before him relied on reports from their officials. But Hadrian wanted to see things for himself. Earlier emperors usually left Rome for wars and came back when the fighting ended. Hadrian's constant travels showed a new way of thinking. He wanted to include people from all provinces in a united empire. He supported creating local towns with their own customs. He did not always force new Roman colonies with Roman laws.

Coins from Hadrian's later rule show him "raising up" different provinces. This showed his goal of helping all parts of the empire. One writer said Hadrian "extended over his subjects a protecting hand." This idea of a united empire was not always popular with traditional Romans. Some thought Hadrian was too much like a Greek, too focused on other cultures.

Building Hadrian's Wall in Britain (122 AD)

Before Hadrian arrived in Britain, there had been a big rebellion from 119 to 121. Many Roman troops were sent to restore order. In 122, Hadrian started building a wall. This wall was meant to separate Romans from "barbarians." The exact reason for the wall is not fully known. It might have been to stop attacks or to mark the empire's limit. It also helped control trade and immigration. Building the wall was cheaper than keeping a large army on the border. Hadrian left Britain by the end of 122. He never saw the finished wall that now carries his name.

Hadrian then traveled through southern Gaul (modern France). He may have overseen the building of a temple in Nîmes. This temple was for Plotina, Trajan's wife, who had recently died. Hadrian spent the winter of 122/123 in Spain. There, he restored the Temple of Augustus.

Travels to Africa and Parthia (123 AD)

In 123, Hadrian crossed the Mediterranean Sea to Mauritania (North Africa). He led a small military campaign against local rebels. He had to cut his visit short because of news about Parthia preparing for war. Hadrian quickly went east. He visited Cyrene, where he helped fund the training of young men for the Roman military. This kind of investment in public good was typical of Hadrian.

Anatolia and Greece (123–125 AD)

When Hadrian reached the Euphrates river, he made a peace deal with the Parthian King. He then checked the Roman defenses and traveled west along the Black Sea coast. He likely spent the winter in Nicomedia. This city had been hit by an earthquake. Hadrian gave money to help rebuild it.

Hadrian traveled through Anatolia. He may have founded a city there after a successful boar hunt. He also helped complete the Temple of Zeus in Cyzicus. This temple received a huge statue of Hadrian. Several cities in the region became important centers for the imperial cult, honoring the emperor.

Hadrian arrived in Greece in the autumn of 124. He took part in the Eleusinian Mysteries, a religious ceremony. He had a special connection to Athens. He even helped revise their laws and added a new tribe named after himself. Hadrian helped Athens by giving money for grain and public games. He also preferred that Greek leaders focus on building useful things like aqueducts. Athens received two new public fountains. Argos, another Greek city, also received fountains to help with its water shortage.

During the winter, Hadrian toured the Peloponnese. He visited Epidaurus and Mantinea. He restored Mantinea's Temple of Poseidon and gave the city its old name back. He also rebuilt ancient shrines in other cities. Hadrian encouraged important Greek nobles to join the Roman Senate. This was a big step in getting Greeks to take part in Roman politics. In March 125, Hadrian attended a festival in Athens. He wore Athenian clothes. He also made sure that the Temple of Olympian Zeus, which had been unfinished for centuries, would finally be completed.

Return to Italy and Africa (126–128 AD)

On his way back to Italy, Hadrian stopped in Sicily. Coins from that time celebrate him as the island's restorer. Back in Rome, he saw the rebuilt Pantheon and his completed villa near Tivoli. In early 127, Hadrian began a tour of Italy. He restored a shrine and improved drainage of a lake. He also divided Italy into four regions. Each region had an imperial governor. This change was not popular with the Roman Senate. It made Italy seem like a group of provinces, not the heart of the empire. This change did not last long after Hadrian's rule.

Hadrian became ill around this time. But his illness did not stop him from visiting Africa in the spring of 128. His arrival brought much-needed rain, ending a drought. He inspected the troops there. Hadrian returned to Italy in the summer of 128. But he soon left for another three-year tour.

Greece, Asia, and Egypt (128–130 AD)

In September 128, Hadrian attended the Eleusinian Mysteries again in Greece. This time, he focused on Athens and Sparta. He had a grand idea for a new Panhellenion. This was a council that would bring all Greek cities together. After setting up the plans, Hadrian went to Ephesus. From Greece, he traveled through Asia to Egypt.

Hadrian arrived in Egypt in August 130. He started his visit by restoring Pompey the Great's tomb. This was important for showing Roman power in the East. Hadrian also went on a lion hunt in the desert. While sailing on the Nile river, Hadrian's close friend, Antinous, drowned.

Hadrian was very sad about Antinous's death. He founded a new city, Antinoöpolis, in Antinous's honor. This city was built in a Greek-Roman style. It was given special benefits. Hadrian also linked an existing Egyptian god, Osiris, with Antinous. This helped connect Roman rule with local beliefs. The cult of Antinous became very popular in the Greek-speaking world. Statues of Antinous were put up all over the empire. Temples were built for him, and festivals were held.

The Third Roman–Jewish War (132–136 AD)

In Roman Judaea, Hadrian visited Jerusalem. The city was still in ruins after an earlier war. He planned to rebuild Jerusalem as a Roman colony. This would give it special rights. Non-Roman people would not have to join Roman religious rituals. But they were expected to support Roman rule. Hadrian may have wanted to combine the Jewish Temple with the Roman imperial cult. This was common in other provinces. But strict Jewish beliefs were more resistant.

A large Jewish uprising began, led by Simon bar Kokhba. The Roman governor asked for an army to crush the resistance. Bar Kokhba punished any Jew who refused to join his fight. Many things may have caused the revolt. These included Roman rule, tensions between rich and poor, and a strong belief in a coming Messiah.

The Romans were surprised by the strength of the revolt. Hadrian called his general Sextus Julius Severus from Britain. He also brought troops from as far away as the Danube. Roman losses were heavy. Hadrian's report on the war to the Senate did not include the usual greeting about his health. This showed how serious the war was. The rebellion was put down by 135 AD. According to one historian, the war caused many deaths and destroyed many towns and villages. Many people were enslaved.

Hadrian removed the province's name from the Roman map. He renamed it Syria Palaestina. He also renamed Jerusalem Aelia Capitolina after himself and a Roman god. He had it rebuilt in a Greek style. The bloody end of the revolt meant the end of Jewish political independence from Rome. In 133, Hadrian fought with his armies against the rebels. He then returned to Rome.

Hadrian's Final Years

Hadrian spent his last years in Rome. In 134, he received an honor for the end of the Third Jewish War. However, celebrations were kept small. Hadrian saw the war as a sad failure of his dream for a peaceful, united empire.

Empress Sabina died in 136. Their marriage had been unhappy. Sabina was declared a goddess after her death.

Choosing a Successor

Hadrian and Sabina had no children. Because of his poor health, Hadrian had to choose a successor. In 136, he adopted Lucius Aelius Caesar. Aelius was the son-in-law of one of the senators Hadrian had removed in 118. Aelius was not very healthy. Some historians think he might have been Hadrian's natural son. Others believe Hadrian adopted him to make peace with important families. Aelius served well as governor of Pannonia. But he died on January 1, 138.

Hadrian then adopted Antoninus Pius. Antoninus had served Hadrian in several important roles. For the empire to remain stable, Hadrian asked Antoninus to adopt two young men. These were Lucius Ceionius Commodus (Aelius Caesar's son) and Marcus Annius Verus (who would become Marcus Aurelius).

Hadrian's last years were difficult. His choice of Aelius Caesar was not popular. His brother-in-law and his grandson were executed for plotting against him.

Hadrian's Death

Hadrian died on July 10, 138, at his villa in Baiae. He was 62 years old and had ruled for 21 years. Ancient writers describe his failing health.

He was first buried near Baiae. Later, his remains were moved to Rome. They were placed in the Gardens of Domitia, near his almost finished mausoleum. When the Mausoleum of Hadrian was completed in 139, his body was cremated. His ashes were placed there with those of his wife and first adopted son. The Senate did not want to declare Hadrian a god. But Antoninus Pius convinced them by threatening to refuse to become emperor. Hadrian was given a temple in Rome. The Senate gave Antoninus the title "Pius" (meaning dutiful) for honoring his adoptive father.

Military Activities

Most of Hadrian's military actions focused on protecting the empire. He wanted to strengthen existing provinces rather than conquer new lands. This was a shift from earlier emperors who sought more wealth and territory. This policy helped the empire as a whole. But military leaders were not happy about fewer chances for glory.

Hadrian gave parts of Dacia to the Roxolani Sarmatians. Their king received Roman citizenship and possibly more money. Hadrian also made a peace treaty with Parthia around 121. Later, the Alani attacked Roman Cappadocia. Hadrian's governor, Arrian, pushed them back. Arrian kept Hadrian informed about the Black Sea region.

Hadrian also built permanent forts and military posts along the empire's borders. These were called limites. This helped keep the army busy during peacetime. His wall in Britain was built by regular soldiers. He also strengthened the Danube and Rhine borders with forts and watchtowers. Soldiers practiced intense drills. Hadrian's coins often showed military images, but his goal was "peace through strength." He focused on disciplina (discipline) in the army.

Hadrian also used less expensive non-citizen troops called numeri. These were ethnic units with special weapons, like archers. They helped with border defense. Hadrian is also known for adding heavy cavalry units to the Roman army.

Legal and Social Changes

Hadrian made the first attempt to organize Roman law. This was called the Perpetual Edict. It meant that the legal actions of officials became fixed laws. Only the Emperor could change them. Hadrian also made the Emperor's legal advisory board a permanent group. It was staffed by paid legal experts. This change showed that the Emperor's power was growing. The new officials were supposed to act for the "Crown," not just the Emperor. However, the Senate did not like losing some of its power. This caused more tension between the Senate and the Emperor.

Hadrian also clarified legal privileges for different social classes. The wealthiest citizens, called honestiores, could pay fines for minor crimes. Lower-ranking people, called humiliores, could face harsh physical punishments for the same crimes. These punishments included forced labor. In the past, Roman citizenship meant more equality under the law. But in imperial courts, punishment depended on a person's social standing.

Hadrian also made rules about dress. Senators and knights were expected to wear the toga in public. He also made sure men and women sat separately in theaters.

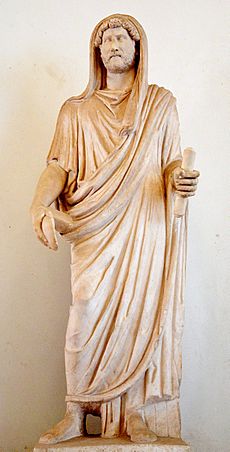

Religious Activities

As Emperor, Hadrian was also Rome's pontifex maximus. This meant he was in charge of all religious matters. He had to make sure official religious groups worked properly. Hadrian's background and love for Greece changed the focus of the official imperial cult. It moved more from Rome to the provinces. His coins showed him linked to traditional Roman spirits. But other coins stressed his connection to Greek gods and Roman protection of Greek culture.

He promoted Sagalassos in Greek Pisidia as a main imperial cult center. His Greek Panhellenion praised Athens as the heart of Greek culture. Hadrian added several imperial cult centers, especially in Greece. Cities chosen as cult centers received imperial support for festivals and games. This brought tourism and trade. Local leaders were encouraged to become cult officials. This helped build respect for the Emperor. Hadrian's rebuilding of old religious sites showed his respect for classical Greece. During his last trip to the Greek East, people showed great religious devotion to Hadrian himself. He was honored as a god. He may have rebuilt the great Serapeum of Alexandria after it was damaged.

In 136, Hadrian dedicated his Temple of Venus and Roma. It was built on land that used to be Nero's Golden House. This temple was the largest in Rome. It was built in a Greek style. The temple honored the Roman goddess Venus, who protected the Roman people. It also honored the goddess Roma, who was a Greek idea. This showed the empire's universal nature.

Hadrian and Christians

Hadrian continued Trajan's policy on Christians. They should not be searched for. They should only be punished for specific crimes, like refusing to swear oaths. Hadrian stated that anyone accusing Christians had to prove their claims. If they could not, they would be punished for making false accusations.

Hadrian's Interests

Hadrian loved art, architecture, and public works. As part of his plan to restore the empire, he founded or rebuilt many towns and cities. He provided them with temples, stadiums, and other public buildings. Examples include the Stadium in Philippopolis (modern Plovdiv). He also rebuilt and enlarged Uskudama, renaming it Hadrianopolis (modern Edirne). Many other towns were also named Hadrianopolis. Rome's Pantheon, a temple to all gods, was rebuilt under Hadrian. His Hadrian's Villa near Tivoli was a huge estate with many buildings.

One story says Hadrian was very proud of his architectural skills. He once offered advice to a famous architect, Apollodorus of Damascus. Apollodorus told him to go draw gourds instead, implying Hadrian knew nothing about real architecture. When Hadrian became emperor, he showed Apollodorus his plans for the huge Temple of Venus and Roma. Apollodorus pointed out its flaws. Hadrian became angry and later had him exiled and killed.

Hadrian loved hunting from a young age.

Hadrian's love for Greek culture might be why he grew a beard. Before him, most emperors were clean-shaven. After Hadrian, all emperors until Constantine the Great wore beards. Hadrian's beard may also have hidden some facial blemishes.

Hadrian was interested in Roman philosophy. He attended lectures by the philosopher Epictetus. He also wrote poetry in both Latin and Greek. One of his most famous poems was written shortly before his death. He also wrote an autobiography. It was published under the name of his freedman, Phlegon. This book was meant to explain his actions and clear up rumors.

Poem by Hadrian

According to an ancient text, Hadrian wrote this poem just before he died:

- Animula vagula blandula

- Hospes comesque corporis

- Quae nunc abibis in loca

- Pallidula, rigida, nudula,

- Nec, ut soles, dabis iocos...

-

-

- P. Aelius Hadrianus Imp.

-

- Roving amiable little soul,

- Body's companion and guest,

- Now descending for parts

- Colourless, unbending, and bare

- Your usual distractions no more shall be there...

How Historians See Hadrian

Hadrian has been called the most versatile Roman emperor. He was seen as someone who hid his true feelings. His successor, Marcus Aurelius, did not mention Hadrian in his writings about people he admired. Hadrian's relationship with the Senate was tense. He was seen as authoritarian. He counted his rule from the day the army named him emperor, not from the Senate's approval. He also used imperial decrees to make laws without the Senate's approval. The tension never became open conflict because Hadrian stayed distant. His constant travels away from Rome probably helped ease the strain.

In 1503, Niccolò Machiavelli saw Hadrian as an ideal ruler. He was one of Rome's Five Good Emperors. Edward Gibbon admired his "vast and active genius" and "equity and moderation." He called Hadrian's time part of the "happiest era of human history." Some historians have called Hadrian a "Führer" or "Duce," meaning a strong, authoritarian leader.

While ancient writers often compared Hadrian unfavorably to Trajan, modern historians look at his reasons and the results of his actions. Some see him as a great Roman reformer. He created a more open absolute monarchy. Robin Lane Fox believes Hadrian created a unified Greco-Roman culture. But he also thinks Hadrian's efforts to "restore" classical culture within an empire without democracy might have taken away its true meaning.

Sources and History

In Hadrian's time, it was hard to write current Roman history. This was because writers feared disagreeing with the emperors. Later Greek writers like Philostratus and Pausanias wrote about Hadrian's rule. They focused on his decisions related to the Greek world. Pausanias especially praised Hadrian's gifts to Greece.

Most of what we know about Hadrian's political history comes from later sources. Some were written centuries after his rule. The early 3rd-century Roman History by Cassius Dio gave an account of Hadrian's reign. But the original is lost. What remains is a short version from the 11th century. It focuses on Hadrian's religious interests, the Jewish war, and his character.

The main source for Hadrian's life is the Historia Augusta. This collection of biographies from the late 4th century is known for being unreliable. However, most modern historians believe its account of Hadrian is mostly accurate. It is likely based on good historical sources from the 3rd century.

Modern historians have used other evidence, like inscriptions and coins, to learn more about Hadrian. The first modern historian to write a detailed account of Hadrian's life was Ferdinand Gregorovius in the 19th century. Later studies have helped create new views of Hadrian. Anthony Birley's 1997 biography of Hadrian combines all these findings.

Nerva–Antonine family tree

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notes:

Except where otherwise noted, the notes below indicate that an individual's parentage is as shown in the above family tree. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

In Spanish: Adriano para niños

In Spanish: Adriano para niños

- Memoirs of Hadrian, a 1951 book about Hadrian's life, written as if he wrote it himself.

- Hadrian, a 2018 opera about Hadrian's life and his relationship with Antinous.

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |