Antinous facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Antinous

|

|

|---|---|

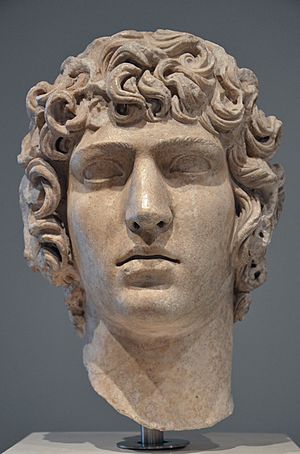

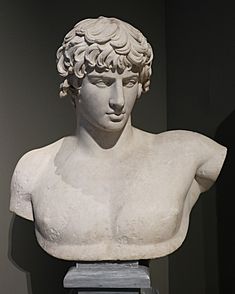

Bust of Antinous from Patras (National Archaeological Museum, Athens)

|

|

| Born | c. 111 Claudiopolis, Bithynia, Roman Empire

|

| Died | c. 130 (aged 18–19) River Nile, Heliopolis, Roman Egypt

|

| Resting place | Hadrian's Villa, Tivoli, Lazio, Italy |

| Partner(s) | Hadrian |

Antinous (Greek: Ἀντίνοος; born around 111 CE – died around 130 CE) was a young Greek man from Bithynia. He became a close companion of the Roman emperor Hadrian. After Antinous died at a young age, Emperor Hadrian ordered that he be made into a god. People worshipped Antinous in both the Greek and Roman parts of the empire. Sometimes he was seen as a god, and sometimes as a hero.

Not much is known about Antinous's early life. He was born in a place called Claudiopolis (now Bolu, Turkey). This area was part of the Roman province of Bithynia et Pontus. He likely met Hadrian in 123 CE and then went to Italy for a good education. By 128 CE, he was a trusted companion of Hadrian. He traveled with the Emperor on a tour of the Roman Empire. Antinous was with Hadrian when they attended important religious events in Athens. He was also with Hadrian when the Emperor bravely killed a lion in Libya. This event was widely shared by the Emperor. In October 130 CE, while traveling on the Nile River, Antinous died under mysterious circumstances.

After Antinous's death, Hadrian declared him a god. He started an organized religion dedicated to Antinous. This worship spread across the Roman Empire. Hadrian also founded a new city called Antinoöpolis near where Antinous died. This city became a main center for worshipping Antinous. Hadrian also started games in memory of Antinous in Antinoöpolis and Athens. Antinous became a symbol of Hadrian's dream to unite all Greek cultures. The worship of Antinous became one of the most popular cults for humans who were made into gods in the Roman Empire. Events honoring him continued long after Hadrian's death.

Antinous has also become a symbol of close male bonds in Western culture. He has appeared in the works of famous writers like Oscar Wilde.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Family

Antinous was born into a Greek family near the city of Claudiopolis. This city was in the Roman province of Bithynia, in what is now north-west Turkey. He was born in a countryside area east of the city. One historian noted that this background made him seem like a "woodland boy" in his statues.

The exact year Antinous was born is not known, but it was likely between 110 and 112 CE. Some early writings say his birthday was in November. Historian Royston Lambert believes it was probably on November 27. Because of where he was born and how he looked, it's thought that some of his family might not have been Greek.

His Name and Background

The name "Antinous" might have come from different places. It could be from a character in Homer's famous poem, the Odyssey. This character was one of Penelope's suitors. Another idea is that it was the male version of Antinoë. She was a woman who helped found Mantineia, a city that had strong ties with Bithynia.

Many historians from the Renaissance thought Antinous was a slave. However, only one old source out of about fifty says this. It is very unlikely he was a slave. It would have been very controversial to make a former slave into a god in Roman society. There is no clear proof about Antinous's family background. However, Lambert thought his family were likely farmers or small business owners. This means they were not from the richest or poorest parts of society. Lambert also believed Antinous probably had a basic education and could read and write.

Life with Emperor Hadrian

Emperor Hadrian spent much of his time traveling across his empire. He arrived in Claudiopolis in June 123 CE. This is probably when he first met Antinous. It's thought that Antinous was chosen to go to Italy. There, he likely studied at a special imperial school in Rome.

Hadrian continued his travels and returned to Italy in September 125 CE. He settled at his villa in Tibur. Over the next three years, Antinous became a very close companion to the Emperor. By 128 CE, Hadrian brought Antinous with him on his travels to Greece.

Hadrian believed Antinous was smart and wise. They both loved hunting, which was seen as a very manly activity in Roman culture. There is no evidence that Antinous ever used his close relationship with Hadrian to gain personal power or wealth.

In March 127 CE, Hadrian, likely with Antinous, traveled through parts of Italy. From 127 to 129 CE, the Emperor was sick with an illness that doctors could not explain. In April 128 CE, he started building a temple in Rome. Antinous may have been with him during this important event. From there, Hadrian toured North Africa, with Antinous by his side.

In late 128 CE, Hadrian and Antinous arrived in Corinth. They then went to Athens, staying there until May 129 CE. Other important people, including Empress Sabina, were with them. In Athens, in September 128 CE, they attended the yearly Great Mysteries of Eleusis. These were ancient Greek religious ceremonies. Hadrian was initiated into a high position there. It is generally believed that Antinous was also initiated at that time.

From Athens, they traveled to Asia Minor. They stayed in Antioch for a year, visiting places like Syria and Judaea. Hadrian became critical of Jewish culture, fearing it went against Roman ways. So, he ordered a temple to be built on the former site of the Jewish Temple. From there, they went to Egypt. They arrived in Alexandria in August 130 CE and visited the tomb of Alexander the Great.

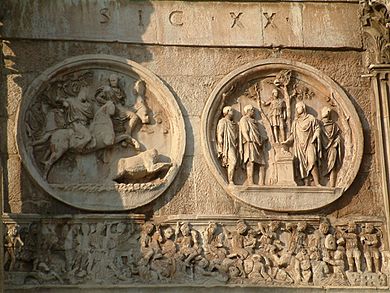

Soon after, probably in September 130 CE, Hadrian and Antinous traveled west to Libya. They had heard about a large lion causing problems for local people. They hunted the lion, and Hadrian saved Antinous's life during the fight. The lion was killed. Hadrian made this event very public. He had bronze medals made, asked historians to write about it, and had a round carving of the hunt created. This carving was later placed on the Arch of Constantine.

Mysterious Death

In late September or early October 130 CE, Hadrian and his group, including Antinous, gathered at Heliopolis. They were going to sail up the River Nile. The group included officials, army leaders, and scholars. Another young aristocrat, Lucius Ceionius Commodus, may also have joined them.

During their journey up the Nile, they stopped at a shrine to the god Thoth. Shortly after this, in October 130 CE, Antinous fell into the river and died. He likely drowned. This happened around the time of the festival of Osiris. Hadrian publicly announced Antinous's death. Soon, rumors spread that Antinous had been killed on purpose. The exact cause of Antinous's death remains a mystery today.

Becoming a God: The Cult of Antinous

Hadrian was very sad about Antinous's death. People at the time said he cried a lot. In Egypt, local priests immediately declared Antinous a god. They connected him with the god Osiris because of how he died. Following Egyptian customs, Antinous's body was probably prepared and mummified. This long process might explain why Hadrian stayed in Egypt until spring 131 CE.

While there, in October 130 CE, Hadrian announced that Antinous was a god. He also said a city should be built where Antinous died, named Antinoöpolis. Making humans into gods was not new in the ancient world. However, officially making a human a god was usually only for the Emperor or his family. So, Hadrian's decision to declare Antinous a god and create a formal religion for him was very unusual. He did this without the Roman Senate's permission. Hadrian was criticized for his deep sadness over Antinous's death. This was especially true because he had delayed making his own sister, Paulina, a goddess when she died.

The worship of Antinous was connected to the worship of the Emperor, but it was still a separate religion. Hadrian also said that a star in the sky was Antinous. He linked the rosy lotus flower growing by the Nile to Antinous.

It is not known exactly where Antinous's body was buried. Some believe his body or special items linked to him were buried at a shrine in Antinoöpolis. However, an old obelisk has writing that strongly suggests Antinous's body was buried at Hadrian's country home, the Villa Adriana in Italy.

It's not clear if Hadrian truly believed Antinous had become a god. He likely also had political reasons for creating the organized religion. It helped to strengthen loyalty to him. In October 131 CE, Hadrian went to Athens. There, he founded the Panhellenion. This was an effort to encourage a sense of Greek identity and unity among the Greek city-states. As a Greek god, Antinous helped Hadrian's goal of uniting all Greeks. In Athens, Hadrian also started a festival in Antinous's honor, called the Antinoeia.

People worshipped Antinous in different ways, depending on their region and culture. In some writings, he is called a divine hero, in others a god, and sometimes both. In Egypt, he was often seen as a spirit. Writings show that Antinous was mainly seen as a kind god. People believed he could help his worshippers and cure their illnesses. He was also seen as someone who had conquered death. His name and image were often put on coffins. In the western parts of the empire, Antinous was linked to the Celtic sun-god Belenos.

Antinoöpolis: A New City

The city of Antinoöpolis was built where an older town called Hir-we once stood. All the old buildings were torn down and replaced, except for the Temple of Ramses II. Hadrian also had political reasons for creating Antinoöpolis. It was the first Greek-style city in the Middle Nile region. It was meant to be a strong center of Greek culture in Egypt.

To encourage Egyptians to join this new Greek culture, Hadrian allowed Greeks and Egyptians in the city to marry. He also allowed the main god of Hir-we, Bes, to continue being worshipped in Antinoöpolis alongside the new main god, Osiris-Antinous. He offered various benefits to encourage Greeks from other places to move to the new city. The city was designed with a grid layout, common for Greek cities. It was decorated with columns and many statues of Antinous, as well as a temple for the god.

Hadrian announced that games would be held in the city in Spring 131 CE to honor Antinous. These games, called the Antinoeia, were held every year for several centuries. They were considered the most important games in Egypt. Events included athletic contests, chariot races, and artistic and musical festivals. Winners could receive citizenship, money, and other prizes.

Antinoöpolis continued to grow into the Byzantine era. It became Christian when the Empire converted. However, it kept a link to magic for centuries. Over time, stones from Hadrian's city were taken to build homes and mosques. By the 18th century, the ruins of Antinoöpolis were still visible. But in the 19th century, the city was almost completely destroyed by local industries. Its stone was used for building and its chalk and limestone were burned for powder.

An excavation of the city in the early 20th century found a realistic funeral portrait painted on wood. The men in the portrait are often thought to be brothers. However, some believe they were close companions. This is because behind one figure is a picture of Antinous-Osiris. This is the only known painting of a statue of the deified young man.

How the Cult Spread

Hadrian wanted the worship of Antinous to spread throughout the Roman Empire. He focused on spreading it in Greek lands. In Summer 131 CE, he traveled to these areas, promoting Antinous by linking him with the more familiar god Hermes. In 131 CE, he announced the building of a temple for Hermes in Trapezus. There, Hermes was probably worshipped as Hermes-Antinous. Although Hadrian preferred to link Antinous with Hermes, Antinous was much more often linked with the god Dionysus across the Empire.

The cult also spread through Egypt. Within a few years, altars and temples to Antinous were built in many cities.

The worship of Antinous was never as large as that of very old gods like Zeus or Dionysus. It was also smaller than the official worship of Hadrian himself. However, it spread quickly across the Empire. Evidence of the cult has been found in at least 70 cities. The cult was most popular in Egypt, Greece, Asia Minor, and North Africa. But many worshippers also lived in Italy, Spain, and northwestern Europe. Items honoring Antinous have been found from Britain to the Danube River.

Even though some people adopted the Antinous cult to please Hadrian, evidence shows it was also truly popular among different social classes. Archaeological finds show that Antinous was worshipped in both public and private places. In Egypt, Athens, Macedonia, and Italy, children were named after the god. Part of the appeal was that Antinous had once been an ordinary human. This made him more relatable than many other gods. His cult also borrowed ideas from other beautiful young male gods and heroes in Greek and Roman stories. Like some of these figures, Antinous was seen as a god who died and was reborn.

At least 28 temples were built for Antinous across the Empire. Most were simple in design. However, those Hadrian was directly involved in, like in Antinoöpolis, were often grander. In most cases, shrines or altars to Antinous were set up near existing temples of the Emperor, Dionysus, or Hermes. Worshippers would give gifts to the god at these altars. There is evidence he was given food and drink in Egypt. Pouring out liquids and making sacrifices were likely common in Greece. Priests dedicated to Antinous oversaw this worship. Some of their names are known from old writings. There is also evidence of oracles (people who could tell the future) at some Antinoan temples.

Sculptures of Antinous became very common. Hadrian likely approved a basic design for sculptors to follow. These sculptures were made in large numbers between 130 and 138 CE. Estimates suggest around 2000 were made, and at least 115 still exist today. Many were found at Hadrian's Villa in Italy. Coins showing Antinous were made in over 31 cities, mostly between 134–35 CE. Many were meant to be medallions, not money. Some even had a hole so they could be worn around the neck as good luck charms. Most production of Antinous items stopped after the 130s. However, followers of the cult continued to use them for several centuries. His cult lasted longer in the Eastern Roman Empire, where his acceptance as a god was better received.

Games honoring Antinous were held in at least 9 cities. These included both athletic and artistic events. The games in some cities were still active in the early 3rd century CE. The cult of Antinous lasted long after Hadrian's reign. Coins with his image were still made during the time of Emperor Caracalla. He was even mentioned in a poem celebrating the rule of Emperor Diocletian, nearly a century after Antinous's death.

Criticism and Decline

The worship of Antinous was criticized by various people, both pagans and Christians. Some pagan critics, like the geographer Pausanias, were doubtful about Antinous being made a god. The Emperor Julian also had doubts. The Sibylline Oracles were generally critical of Hadrian. The pagan philosopher Celsus criticized the cult for what he saw as bad behavior among its Egyptian followers. He compared it to Christianity in this way.

Christian writers like Tertullian and Origen also condemned the Antinous cult. They saw it as a disrespectful rival to Christianity. They insisted that Antinous was just a human. They linked his cult to evil magic and claimed Hadrian forced people to worship him out of fear.

During the conflicts between Christians and pagan worshippers in Rome in the 4th century, Antinous was supported by pagans. As a result, the Christian poet Prudentius spoke out against his worship in 384 CE. Many sculptures of Antinous were destroyed by Christians and by invading tribes. However, some were later put back up. The Antinous statue at Delphi was knocked down and broken, but later put back in a chapel. Many images of Antinous remained in public places until pagan religions were officially banned under Emperor Theodosius in 391 CE.

Today, some modern groups who follow ancient pagan religions have started to honor Antinous again. Because of his close bond with Hadrian, Antinous's modern worship often appeals to people in the LGBT community, especially gay men. He is seen as a symbol of connection and friendship.

Antinous in Roman Art

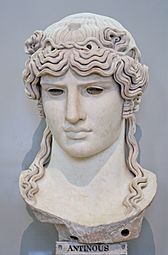

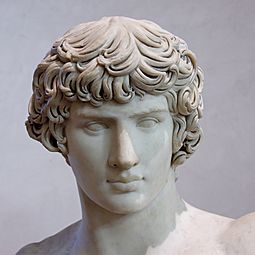

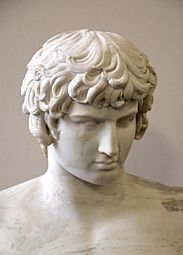

Hadrian asked Greek sculptors to create images of Antinous. These sculptures showed his thoughtful beauty and graceful body. This led to what is called "the last great flowering of classical art." It is believed that most of these statues were made between Antinous's death in 130 CE and Hadrian's death in 138 CE. It's thought that official models were sent to workshops across the empire to be copied, with some local changes allowed. Many of these sculptures share special features: a wide chest, curly hair, and a downward gaze. These features make them easy to recognize.

About one hundred statues of Antinous have survived to modern times. This is amazing, considering that his cult was strongly opposed by Christians. Many Christians damaged and destroyed statues and temples built in his honor. By 2005, a historian noted that more images of Antinous have been found than of almost any other figure from ancient times, except for Augustus and Hadrian. She also said that studying these images of Antinous is important because of his "rare mix" of mystery and strong physical presence.

There are also statues in many archaeological museums in Greece. These include museums in Athens, Patras, Chalkis, and Delphi. While these images might be idealized, they show what all writers of the time described as Antinous's amazing beauty. Although many sculptures look similar, some show differences in how soft or strong his features and pose are. In 1998, large remains were found at Hadrian's Villa. Archaeologists thought they might be from Antinous's tomb or a temple to him. However, this idea has been questioned. Some ancient writings suggest Antinous was buried at his temple in Antinoöpolis, the Egyptian city founded in his honor.

- Depictions of Antinous

-

Antinous as Bacchus at the Vatican Museums

-

Antinous Mondragone at the Louvre

-

Antinous with a Greek-style headband, Palazzo Massimo alle Terme

-

Antinous as Osiris. Staatliches Museum Ägyptischer Kunst

-

Bust (130–138 AD) in the National Museum of Fine Arts in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Studying Antinous's Life

Historian Caroline Vout noted that most writings about Antinous's life are short and were written after Hadrian's time. This means it's "impossible to create a detailed biography." Thorsten Opper from the British Museum also said that "Hardly anything is known of Antinous's life." He added that sources become more detailed the later they are, which doesn't make them more trustworthy. Antinous's biographer, Royston Lambert, agreed. He said information about Antinous is "tainted always by distance, sometimes by prejudice."

See Also

In Spanish: Antínoo para niños

In Spanish: Antínoo para niños

- Antinous (constellation)

- Antinous Farnese

- Antinous Mondragone

- Capitoline Antinous

- Statue of Antinous (Delphi)

- Townley Antinous

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |