Pompey facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Pompey

|

|

|---|---|

| Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus | |

|

|

| Born | 29 September 106 BC Picenum, Italy

|

| Died | 28 September 48 BC (aged 57) Pelusium, Egypt

|

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Resting place | Albanum, Italy |

| Occupation | Military commander and politician |

| Office | Consul (70, 55, 52 BC) |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives | Pompeia gens |

| Military career | |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | 3 Triumphs |

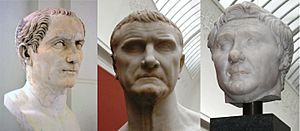

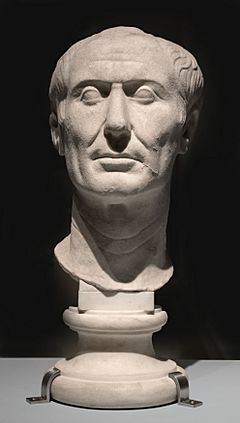

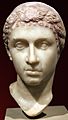

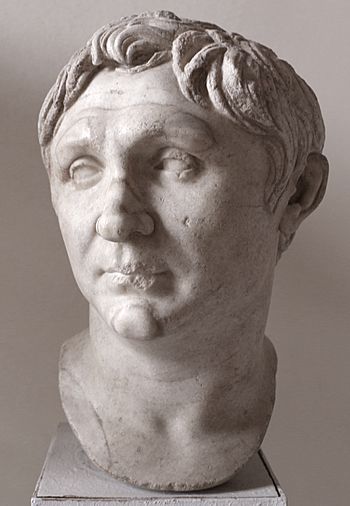

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (born September 29, 106 BC – died September 28, 48 BC), known as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a powerful Roman general and leader. He played a huge part in Rome's change from a republic (where people voted for leaders) to an empire (ruled by one powerful person). Early in his career, he was a supporter of the Roman general Sulla. Later, he became a friend and then a rival of Julius Caesar.

Pompey came from a noble family. He started his military career when he was young. He became famous serving the Roman leader Sulla during a civil war in 83–82 BC. Because he was so successful as a young general, he became a Roman consul (a top government official) without following the usual steps. He was elected consul three times (70, 55, and 52 BC). He also celebrated three Roman triumphs, which were big parades to celebrate military victories. His early success earned him the nickname Magnus, meaning "the Great," like his hero Alexander the Great.

In 60 BC, Pompey joined Crassus and Caesar in a secret political team called the First Triumvirate. This alliance was made stronger when Pompey married Caesar's daughter, Julia. After Julia and Crassus died, Pompey joined a group of conservative senators called the optimates. Pompey and Caesar then started to fight for control of Rome. This led to Caesar's Civil War. Pompey was defeated at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC. He went to Egypt for safety, but he was killed there by the people working for King Ptolemy XIII.

Contents

- Early Life and Rise to Power

- Sertorian War and First Consulship

- Campaign Against the Pirates (67 BC)

- The Third Mithridatic War and Re-Organization of the East

- Return to Rome and the First Triumvirate

- From Confrontation to Civil War

- The Road to Pharsalus

- Death

- Pompey's Military Skills

- His Legacy

- Family Life

- Pompey's Theater

- Timeline of Pompey's Life

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Life and Rise to Power

Pompey was born around 106 BC in Picenum, a region in Italy. His father, Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, was a local noble. Strabo was the first in his family to become a senator in Rome. Because of this, he was sometimes looked down on as a "new man." Pompey started his career serving in his father's army during the Social War (91–87 BC).

Pompey's father died in 87 BC. Pompey was accused of a crime his father supposedly committed. He was found innocent, perhaps after agreeing to marry the judge's daughter, Antistia.

Later, in 84 BC, a new civil war began when Sulla returned to Italy. Pompey gathered soldiers from his home region to support Sulla. Sulla admired Pompey's skills. He convinced Pompey to divorce Antistia and marry Sulla's stepdaughter, Aemilia. She was already pregnant and died soon after giving birth.

Around 79 BC, Pompey married Mucia Tertia. They had three children: Gnaeus, Pompeia Magna, and Sextus. They divorced in 63 BC.

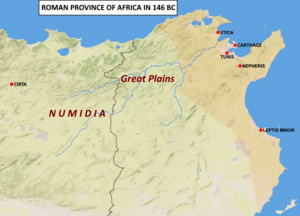

Campaigns in Sicily and Africa

After Sulla's civil war, some of his enemies escaped to Sicily and Africa. Sulla sent Pompey to Sicily with a large army. Pompey quickly took control of Sicily. He captured one of Sulla's enemies, Carbo, and had him executed. This action led his opponents to call Pompey adulescentulus carnifex, meaning "young butcher," because of his strictness.

Sulla then ordered Pompey to retake Africa. Pompey defeated and killed another enemy general there. He also invaded Numidia, a kingdom allied with Rome's enemies. He quickly took control, executed the king, and put a new king on the throne. When he returned to Rome, Sulla gave him the nickname Magnus, or "the Great."

Pompey then asked for a special parade called a triumph to celebrate his victories. This was unusual because he was so young and had not held a high political office yet. Sulla first said no, but Pompey refused to send his army home until he got his triumph. Pompey held his triumph on March 12, 80 BC.

After Sulla died, a leader named Marcus Aemilius Lepidus started a rebellion. The Senate asked Pompey to help. Pompey quickly gathered soldiers and defeated Lepidus's forces. He showed his skill as a military leader once again.

Sertorian War and First Consulship

Sertorian War in Hispania

The Sertorian War started in 80 BC in Hispania (modern-day Spain and Portugal). A Roman general named Quintus Sertorius led a rebellion there. He was joined by other enemies of Sulla. Pompey asked the Senate to send him to Hispania to deal with the situation. He was made a proconsul, which was technically against the rules since he hadn't held a public office before.

Pompey gathered 30,000 foot soldiers and 1,000 horsemen. This showed how serious the threat from Sertorius was. Pompey arrived in Hispania in early 76 BC. He was defeated by Sertorius at the Battle of Lauron. This was a setback for Pompey.

In 75 BC, Pompey defeated some of Sertorius's allies near Valencia. He then fought Sertorius himself at the Battle of Sucro and Saguntum. These battles were tough, and Pompey lost many men.

Sertorius was eventually betrayed and murdered by his own officers in 71 BC. His replacement, Perpenna, was then defeated and executed by Pompey. This ended the Sertorian War. Pompey stayed in Hispania to bring peace to the region. He showed a talent for organizing and earned the loyalty of many people there.

Pompey's First Consulship

While Pompey was in Hispania, another general, Crassus, was fighting a slave rebellion led by Spartacus in Italy. Pompey returned to Italy just as Crassus was finishing the war. Pompey's soldiers helped to capture and kill 6,000 escaped slaves. Pompey claimed he had ended the war, which made Crassus very angry.

Pompey was given a second triumph for his victory in Hispania. He was also nominated to be a consul, even though he was too young and didn't meet the usual requirements. The Senate had to make a special rule for him. Pompey and Crassus were elected consuls for 70 BC. They often disagreed, but their time as consuls did bring back important powers to the plebeian tribunes, which Sulla had taken away. This was a big change in Roman politics.

Campaign Against the Pirates (67 BC)

Piracy was a huge problem in the Mediterranean Sea. Pirates attacked Roman ships and even kidnapped senators. In 68 BC, they raided Rome's port, Ostia. Pompey saw this as a chance to gain more power. He asked a tribune named Aulus Gabinius to create a law that would give him command against the pirates.

The new law, called the Lex Gabinia, gave Pompey great power for three years. He could operate in any province within 50 miles of the Mediterranean Sea. He also got a lot of money and the power to appoint his own officers. The Senate and consuls were worried about giving so much power to one man, but the law was very popular with the people and passed.

Pompey divided his forces across the Mediterranean to stop the pirates from escaping. He secured the routes for grain coming to Rome. He took control of the western Mediterranean in just 40 days. Then, his fleets moved east, pushing the pirates back to their main bases in Cilicia. Pompey led the final attack on their stronghold, winning the Battle of Korakesion. The war against the pirates was over in only three months.

Most pirates surrendered because Pompey was known for being fair. He gave them land in cities that had been damaged during other wars. These communities became loyal to Rome and to Pompey.

The Third Mithridatic War and Re-Organization of the East

Third Mithridatic War

In 73 BC, another Roman general, Lucullus, was fighting the Third Mithridatic War. This war started when the king of Bithynia died and left his kingdom to Rome. This led to an invasion by Mithridates VI of Pontus and Tigranes the Great of Armenia. Lucullus was a good general, but his troops were tired and unhappy by 69 BC.

In 66 BC, Pompey saw another chance to gain power. He used a new law, the lex Manilia, to get command of the war against Mithridates. This law gave him even more power in Asia Minor, on top of the power he already had from fighting the pirates. The senators were privately upset that one man had so much power, but they let it pass because Pompey was so popular.

Lucullus was angry about being replaced. He called Pompey a "vulture" who took credit for others' work. Pompey made an alliance with Phraates III, the king of Parthia, and convinced him to invade Armenia. Mithridates offered a truce, but Pompey demanded terms that could not be accepted. Pompey then defeated Mithridates at the Battle of the Lycus in late 66 BC.

Mithridates escaped to the Black Sea. Pompey then invaded Armenia. Tigranes, the Armenian king, quickly made peace with Rome. He paid a large sum of money and allowed Roman troops in his land.

In 65 BC, Pompey went to take control of the region of Colchis. He fought and defeated several local tribes. He then wintered in Armenia, settling small border disputes.

Pompey used his navy to blockade Mithridates. In 64 BC, he took over the rich cities of Syria, making it a new Roman province. This brought a lot of money and fame to Pompey. Meanwhile, Mithridates was cornered by one of his sons and was killed. His son sent Mithridates' body to Pompey. In return, the son was given the Bosporan Kingdom and became an ally of Rome.

Re-organization of the East

Pompey's victories allowed him to reorganize the entire eastern part of the Roman world. In early 63 BC, he marched south through Syria. He captured independent cities and reached Damascus, completing the takeover of Syria.

In Judea, two brothers were fighting for control. Both asked Pompey for his help. Pompey marched into Judea and forced one of the brothers to surrender Jerusalem. The city's defenders refused to give up and hid in the Temple. The Romans stormed and looted the Temple. One brother was made ruler, but Judea became a client kingdom, meaning it was controlled by Rome. Its northern part was reorganized into a group of cities called the Decapolis. Both Judea and the Decapolis were placed under the new Roman province of Syria.

Pompey also merged parts of Pontus with Bithynia, creating a new province called Bithynia and Pontus. He divided other territories among Roman allies. These actions greatly increased Rome's income and Pompey's personal wealth and influence.

Return to Rome and the First Triumvirate

Pompey returned to Italy in 62 BC. There were rumors that he planned to use his army to become a king, but he sent his army home when he arrived. Huge crowds came to see his victory parade in Rome. This showed that even though some senators were against him, Pompey was still very popular with the common people.

Pompey's achievements in Asia Minor earned him a third triumph, which he celebrated on his 45th birthday in 61 BC. He claimed to have greatly increased Rome's yearly income. He also gave a huge amount of treasure to the state. Pompey used some of his wealth to start building the famous Theatre of Pompey in Rome.

However, the Senate refused to approve the treaties Pompey had made in the East. They also blocked a law to give land to his soldiers and poor citizens. This made Pompey angry.

Pompey couldn't get what he wanted from the Senate alone. But the situation changed when Julius Caesar sought his support. Caesar was a very ambitious politician. An alliance with Pompey allowed Caesar to use Pompey's popularity with the people. With Crassus also supporting him, Caesar became one of the two consuls for 59 BC.

This led to the formation of the First Triumvirate. This was an unofficial political alliance between Pompey, Crassus, and Caesar. It was designed to work against the conservative senators. Pompey's power came from his military fame and popularity. Crassus was said to be the richest man in Rome. Caesar, though the youngest, became central to the group.

Caesar immediately proposed a new law to give land to the poor. Pompey's soldiers filled the streets of Rome, helping the law pass. Caesar also made sure that Pompey's settlements in the East were approved. Pompey also married Caesar's daughter, Julia, to strengthen their alliance.

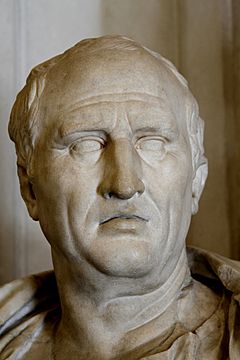

Pompey used a popular politician named Publius Clodius Pulcher to attack Cicero, a senator who opposed the triumvirate. Clodius managed to get Cicero exiled from Rome. But when Clodius turned against Pompey, Pompey helped bring Cicero back. When there were food shortages in 58 BC, Pompey was put in charge of the food supply. He quickly solved the problem, which made him very popular.

The alliance started to show signs of trouble. Pompey and Crassus didn't fully trust each other. Pompey also felt that Caesar's success in Gaul was threatening his own fame as Rome's top general. In 56 BC, the three leaders met to discuss their plans. Pompey and Crassus agreed to run for consul together in 55 BC, with Caesar's support. They won, after a lot of fighting and unrest during the elections.

As consuls, they passed laws that gave Crassus control of Syria and a command against Parthia. Pompey was given control of Hispania and Africa. Caesar's governorships in Gaul were extended. All three men were given these powerful positions for five years.

From Confrontation to Civil War

In 54 BC, Pompey's wife, Julia, died during childbirth. This, along with the death of Crassus in battle in 53 BC, removed the main things holding Caesar and Pompey's alliance together. They began to move towards a direct conflict.

In 52 BC, there was so much violence in Rome that the elections for consul had to be stopped. The Senate, including Pompey's former opponents, now suggested that Pompey be made sole consul. This was a very unusual step. Pompey restored order and then married Cornelia, the daughter of a senator named Metellus Scipio Nasica. He made Metellus Scipio his co-consul for the rest of the year.

As consul, Pompey helped pass laws that made it harder for Caesar. New laws allowed for past crimes to be prosecuted. This meant Caesar could be put on trial as soon as he left Gaul and lost his special protection. Another law required candidates for consul to be physically present in Rome. Caesar wanted to run for consul while still in Gaul.

Even though they worked together in public, Pompey increasingly saw Caesar as a threat. Many senators also felt this way. The consuls elected for 50 BC were both opponents of Caesar. They tried to remove Caesar from his command in Gaul. Caesar reportedly bribed some officials to block this. One tribune suggested that both Caesar and Pompey should give up their armies at the same time. This was popular with senators who wanted to avoid war, but the conservative senators rejected it.

When Pompey became ill while recruiting soldiers, the celebrations for his recovery made him too confident that his popularity would help him win any fight. Rome was heading towards civil war. Caesar crossed the Rubicon river into Italy with one army.

On January 1, 49 BC, Caesar sent a message saying that if his demands weren't met, he would march on Rome. On January 7, the Senate declared Caesar a public enemy. Four days later, Caesar crossed the Rubicon, officially starting the civil war.

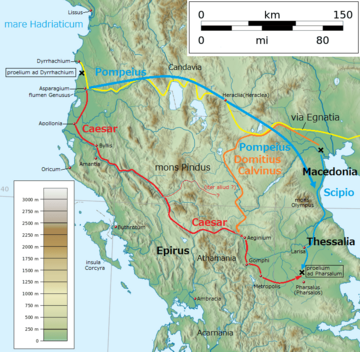

The Road to Pharsalus

When the war began, Pompey had the resources of the Roman state and many allies in the East. Caesar was a rebel with a smaller army and no navy. But Pompey's position was not as strong as it seemed. He was just an advisor to the Senate, and many senators didn't fully trust him. Military decisions had to be approved by the consuls, and Pompey could only suggest, not order.

Caesar moved very quickly, advancing on Rome with little resistance. His troops were experienced veterans. Pompey's men were new recruits, and they lacked good coordination. Pompey abandoned Rome and ordered all senators and officials to go with him. He moved his troops across the Adriatic to Dyrrhachium in Thessaly, Greece. He did this almost perfectly.

Caesar couldn't follow him without ships. So, he first secured his control of Italy and then defeated Pompey's forces in Hispania. This gave Pompey time to train his new soldiers. He built an army that was almost twice the size of Caesar's. Pompey's navy also controlled the sea.

Despite this, in January 48 BC, Caesar managed to cross the Adriatic and land in what is now southern Albania. He captured some towns and advanced towards Pompey's main supply base at Dyrrhachium. Pompey arrived in time to stop Caesar and set up a fortified camp. The two armies stayed there until spring. Neither general wanted to fight a big battle yet. Caesar was too weak, and Pompey preferred to cut off Caesar's supplies and starve him out.

In April, Caesar received more troops. He was strong enough to defend his lines, but he couldn't take Dyrrhachium. His men were also running low on food. Pompey had plenty of supplies by sea, but Caesar had blocked local rivers, making water scarce for Pompey's army. In late July, Pompey broke through Caesar's defenses. Caesar decided to retreat to Apollonia.

Pompey's allies then joined him in Thessaly. Caesar moved south to meet this new threat. Pompey pursued him to the area near Pharsalus. Pompey's army had about 38,000 men, while Caesar had 22,000. Pompey also had many more cavalry (7,000 to Caesar's 1,000).

On August 9, Pompey set up his army for battle. He planned to use his stronger cavalry to attack Caesar's left side. But Caesar had expected this. He pushed back Pompey's cavalry, which then fled. This exposed the soldiers behind them. Pompey's army collapsed under pressure from both sides. This was Pompey's only major defeat.

Death

After his defeat, Pompey fled to prevent Caesar from gathering more forces. He stopped at Amphipolis to collect money. He then left and went to Mytilene, on the island of Lesbos, to pick up his wife Cornelia and his son. Pompey sailed on, stopping only for food or water. He reached Attaleia (Antalya) where some warships were waiting for him.

Pompey thought about going to Parthia, but he was advised that the king was not trustworthy and it might be unsafe for his wife. Instead, he was told to go to Egypt. Egypt was only three days away by ship. Its young king, Ptolemy XIII, owed Pompey a favor because Pompey had helped his father.

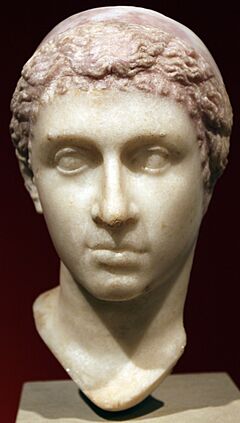

Pompey sailed from Cyprus with warships and merchant ships. He heard that Ptolemy was in Pelusium, fighting his sister Cleopatra VII, whom he had removed from power. Pompey sent a messenger to Ptolemy asking for help.

Ptolemy's advisors, including Potheinus, Theodotus, and Achillas, held a meeting. Theodotus argued that neither welcoming Pompey nor turning him away was safe. If they welcomed him, Pompey would become powerful, and Caesar would become an enemy. If they turned him away, Pompey would blame them, and Caesar would keep chasing him. Theodotus suggested killing Pompey to get rid of the problem and please Caesar.

On September 28, Achillas went to Pompey's ship in a small fishing boat. He was joined by Lucius Septimius, who had once been one of Pompey's officers, and another assassin. Pompey's friends were suspicious of this simple arrival. They told Pompey to go back to open sea, away from the Egyptians. But Achillas claimed the shallow water prevented a larger ship from coming closer.

Pompey boarded the small boat. He noticed the lack of friendliness. He told Septimius that he was an old friend. Septimius just nodded and then stabbed Pompey with a sword. Achillas and the other assassin also attacked him with daggers. The people on Pompey's ship watched in horror and fled.

Pompey's body was thrown into the sea. Philip, one of Pompey's servants, wrapped the body in his tunic and built a funeral fire on the shore. Pompey died the day before his 58th birthday.

When Caesar arrived in Egypt a few days later, he was shocked. He turned away in disgust when someone brought him Pompey's head. When Caesar was given Pompey's seal ring, he cried. Pompey's remains were later taken to his wife Cornelia, who buried them at his home in Italy.

Pompey's Military Skills

Pompey was famous for his military victories for two decades. Some people, like Sertorius and Lucullus, sometimes criticized his tactics. Pompey's methods were usually effective, but not always new or imaginative. However, the Battle of Pharsalus was his only major defeat. Sometimes, he didn't like to risk a big open battle. While not extremely charming, Pompey was brave and skilled in battle, which inspired his soldiers. He also gained a reputation for taking credit for other generals' victories.

On the other hand, Pompey is seen as an excellent strategist and organizer. He could win campaigns without being a genius on the battlefield. He did this by constantly outsmarting his opponents and slowly pushing them into difficult situations. Pompey was a great planner and had amazing organizational skills. This allowed him to plan big strategies and lead large armies effectively. During his campaigns in the East, he chased his enemies without stopping, choosing where to fight his battles.

Most importantly, he could adapt to his enemies. Many times, he acted very quickly and decisively, like when he fought in Sicily and Africa, or against the Cilician pirates. During the Sertorian War, Pompey was beaten several times by Sertorius. So, he decided to fight a "war of attrition." This meant he avoided big battles against Sertorius himself. Instead, he tried to slowly gain control by capturing fortresses and cities and defeating Sertorius's junior officers. This strategy wasn't flashy, but it led to constant gains and lowered the morale of Sertorius's forces. By 72 BC, Sertorius was in a desperate situation, and his troops were leaving him. When he fought Perpenna, who was a much weaker tactician, Pompey returned to a more aggressive strategy and won a decisive victory that ended the war.

Even against Caesar, his strategy was smart. During the campaign in Greece, he managed to regain control. He joined his forces with Metellus Scipio (which Caesar wanted to prevent) and trapped his enemy. His strategic position was much better than Caesar's. He could have starved Caesar's army. However, his allies finally forced him to fight an open battle. His traditional tactics were no match for Caesar's, who also had more experienced troops.

His Legacy

For historians of his time and later, Pompey was seen as a great man who achieved amazing victories through his own efforts. But he then lost power and was eventually killed by betrayal.

He was a hero of the Republic. He once seemed to control the Roman world, only to be defeated by Caesar. Pompey was seen as a tragic hero almost immediately after his defeat and murder.

The writer Plutarch described Pompey as a Roman Alexander the Great. He was seen as pure of heart and mind, destroyed by the selfish ambitions of those around him. This image of Pompey continued through later periods, like in the play The Death of Pompey (1642).

Even though he fought against Caesar, Pompey was still celebrated during the Roman Empire as the conqueror of the East. For example, pictures of Pompey were carried in Augustus's funeral procession. He had many statues in Rome because he was a triumphator (someone who celebrated a triumph). While the emperors didn't honor Pompey as much as they did Caesar, who was considered a god, many nobles and historians thought Pompey was just as great, or even greater, than Caesar.

Family Life

Pompey was married five times. These marriages were not just about love. They were also political agreements. They often helped Pompey's career and his need to form alliances with other powerful Roman men.

- His first marriage, in 86 BC, was to Antistia.

- In 82 or 81 BC, he divorced Antistia to marry Sulla's stepdaughter, Aemilia. She died soon after giving birth.

- He married Mucia Tertia in 79 BC. This marriage gave him an alliance with the powerful Caecilia family. He divorced Mucia in 61 BC, possibly for political reasons.

- He married Julia, the daughter of his political rival Julius Caesar, in 59 BC.

- After Julia's death in 54 BC, he married Cornelia Metella. She was with him when he was killed in 48 BC.

Pompey had three children who lived to adulthood, all with Mucia Tertia:

- Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, who was executed in 45 BC.

- Pompeia Magna, who had children.

- Sextus Pompey, who later rebelled against Augustus in Sicily.

His fourth wife, Julia, died giving birth to a child who lived only a few days. We don't know the gender of the child.

Pompey's Theater

After returning from his campaigns in the East, Pompey spent a lot of his new wealth on building projects. The biggest of these was a huge stone theater complex in Rome. It was Rome's first stone theater and an important building in Roman architecture.

Pompey bought hundreds of paintings and statues to decorate the theater. He also supported artists of his time.

On August 12, 55 BC, the Theater of Pompey was officially opened. It could hold about 10,000 people. It had a temple dedicated to Venus (Pompey's special goddess) built at the back of the seating area. The seats formed the steps leading up to the temple. Next to the theater was a large rectangular garden with covered walkways. These walkways were decorated with paintings. There were also many statues, including fourteen statues representing the nations Pompey had conquered. A statue of Pompey himself was placed in a large hall connected to the garden, where Senate meetings could be held.

Pompey built a house near the theater. It was more splendid than his old house, but not so grand that it would make people jealous.

Timeline of Pompey's Life

- 29 September 106 BC – Born in Picenum.

- 89 BC – Serves in his father's army during the Social War.

- 83 BC – Joins Sulla after Sulla returns from war.

- 82 BC – Marries Aemilia at Sulla's request; she dies soon after.

- 82–81 BC – Defeats Gaius Marius's allies in Sicily and Africa.

- 81 BC – Returns to Rome and celebrates his first triumph.

- 80 BC – Pompey marries Mucia.

- 79 BC – Pompey helps elect Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, then puts down Lepidus's rebellion.

- 76–71 BC – Fights in Hispania against Sertorius.

- 71 BC – Returns to Italy and helps end the slave rebellion led by Spartacus; earns his second triumph.

- 70 BC – First consulship (with Marcus Licinius Crassus).

- 67 BC – Defeats the pirates.

- 66–61 BC – Defeats King Mithridates of Pontus, ending the Third Mithridatic War.

- 64–63 BC – Marches through Syria, the Levant, and Judea.

- 29 September 61 BC – Celebrates his third triumph.

- April 59 BC – The first triumvirate is formed. Pompey allies with Julius Caesar and Crassus, marrying Caesar's daughter Julia (wife of Pompey).

- 58–55 BC – Governs Hispania by proxy while the Theater of Pompey is built.

- 55 BC – Second consulship (with Marcus Licinius Crassus); the Theater of Pompey is opened.

- 54 BC – Julia dies, and the first triumvirate weakens.

- 52 BC – Serves as sole consul for a short time, then as consul with Metellus Scipio for the rest of the year, marrying Metellus Scipio's daughter Cornelia Metella.

- 51 BC – Forbids Caesar (who is in Gaul) from running for consul without being in Rome.

- 50 BC – Becomes very ill in Campania but recovers.

- 49 BC – Caesar crosses the Rubicon river and invades Italy. Pompey retreats to Greece with his allies.

- 48 BC – Caesar defeats Pompey's army near Pharsalus, Greece. Pompey flees to Egypt and is killed at Pelusium.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Pompeyo para niños

In Spanish: Pompeyo para niños