Quintus Sertorius facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Quintus Sertorius

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

This coin was made in Osca, Sertorius' capital city, during his fight against Rome. It says "BOLSKAN" in ancient Iberian writing.

|

|||||||||

| Born | c. 126 BC Nursia, Sabinum

|

||||||||

| Died | 73 or 72 BC (aged 53–54) Osca, Hispania

|

||||||||

| Cause of death | Assassination | ||||||||

| Occupation | Statesman, lawyer, general | ||||||||

| Known for | Rebellion in Spain against the Roman Senate | ||||||||

| Office |

|

||||||||

| Military career | |||||||||

| Allegiance | Roman Republic Marius–Cinna faction |

||||||||

| Battles/wars | Cimbric War Social War Bellum Octavianum Sulla's civil war Sertorian War X |

||||||||

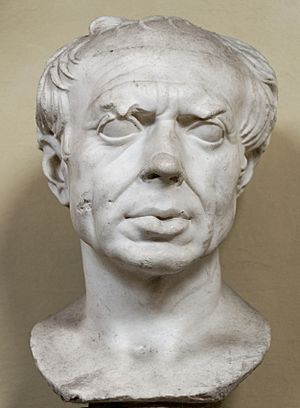

Quintus Sertorius (born around 126 BC – died 73 or 72 BC) was a Roman general and a leader in government. He led a big rebellion against the Roman Senate in Hispania (modern-day Spain and Portugal). Sertorius became the independent ruler of this region for almost ten years. Sadly, he was killed by his own officers.

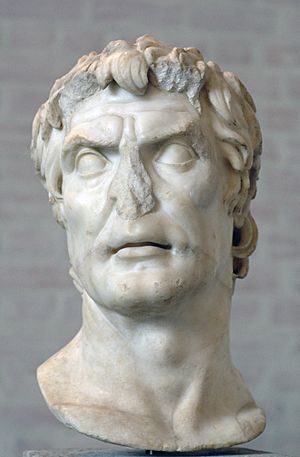

Sertorius first became known during the Cimbrian War, fighting under a famous general named Gaius Marius. He then served Rome in the Social War. Later, he joined forces with Cinna and Marius during a short civil war in 87 BC. He helped attack Rome and tried to stop the harsh punishments that followed.

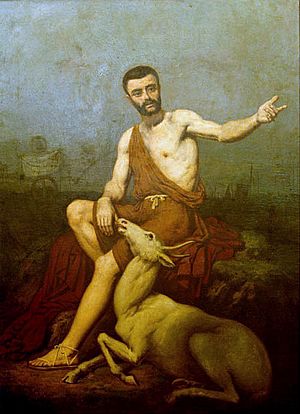

After a powerful Roman leader named Sulla took control, Sertorius was declared an enemy. He was forced to leave Hispania, where he was serving as governor. But he soon returned in 80 BC. He gathered many Roman exiles and local Iberian tribes to fight against Sulla's government in Rome. Sertorius used clever, unexpected fighting methods. He even used a tame white fawn to make people believe he was a religious leader.

Sertorius allied with Mithridates VI of Pontus and even some pirates to help him in his fight. The Roman government sent strong generals like Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius and Pompey to stop him. But they struggled for a long time. After defeating Pompey in 76 BC, Sertorius faced more difficulties. By 73 BC, his allies started to lose faith in him. His own officer, Marcus Perperna Veiento, assassinated him. Soon after, Pompey defeated Sertorius's remaining forces.

Contents

Early Life and Military Service

Sertorius was born in Nursia, a town in Italy, around 126 BC. His family was not from the highest Roman noble class, so he was considered a "new man" in politics. This meant he was the first in his family to join the Roman Senate.

Sertorius's father died when he was young. His mother, Rhea, worked hard to give him the best education. He loved his mother very much. Like many young men from the countryside, he moved to Rome to start a political career. He hoped to become a good speaker and a lawyer.

After his time in Rome, Sertorius joined the military. His first recorded battle was in 105 BC. He showed great courage and escaped even after being wounded. He swam across the Rhone River with his weapons and armor. This became a small legend.

Sertorius served under the famous general Gaius Marius. He spied on Germanic tribes that had defeated Roman armies. He gathered important information about their numbers and plans. Sertorius became well-known and trusted by Marius. He likely fought in Marius's big victories in 102 BC and 101 BC. Many experts believe Sertorius learned a lot from Marius. He used similar fighting tactics later in his own rebellion.

In 97 BC, Sertorius went to Hispania Citerior as a military tribune. He served under the governor, Titus Didius. In one town, Castulo, the Roman soldiers were causing trouble. The local people invited a neighboring tribe to help them. They attacked and killed many Roman soldiers. Sertorius escaped, gathered the remaining Romans, and then attacked the town. He killed the male attackers and sold others into slavery.

This event made Sertorius famous in Hispania. It helped him later in his career. He learned about guerrilla warfare from the Iberian people. This was a type of fighting where small groups use surprise attacks and quick movements. He would use these tactics very effectively in his own revolt.

Political Struggles in Rome

In 92 BC, Sertorius became a quaestor, a Roman official who managed money. He was sent to Cisalpine Gaul (northern Italy). During this time, the Social War broke out in Italy. Sertorius helped by gathering soldiers and weapons. He also fought as a commander. He was wounded in the face during the war, losing an eye.

Sertorius used his wound to his advantage. He would say that other men had to put away their awards, but his proof of bravery was always with him. When he returned to Rome, he was seen as a war hero.

Sertorius tried to become a tribune of the Plebs, a powerful position, but Lucius Cornelius Sulla stopped him. Sulla was a rival of Marius, whom Sertorius had supported. This made Sertorius oppose Sulla.

Civil War and Exile

In 88 BC, Sulla marched his army on Rome and took control. He punished his enemies and sent Marius away. Sulla then left Italy to fight a war in the East. After Sulla left, fighting broke out between his supporters and his opponents, led by Lucius Cornelius Cinna. Sertorius joined Cinna and his allies.

Cinna was driven out of Rome in 87 BC. Sertorius helped him gather an army to march back on Rome. When Marius returned from exile to help, Sertorius was worried. He feared Marius's anger and what he might do. But he agreed to Marius's return because Cinna had invited him.

When Cinna's forces took Rome, Sertorius tried to stop the killings and punishments that followed. After Marius died, Sertorius helped to control Marius's slave army, which was terrorizing Rome.

Sulla returned to Italy in 83 BC, starting another civil war. Sertorius was chosen to lead some of the forces against Sulla. He was part of the staff of Consul Scipio Asiaticus. Sertorius advised Scipio not to trust Sulla during peace talks. He warned against letting Sulla's soldiers mix with theirs. But Scipio did not listen. Sulla's soldiers convinced Scipio's army to switch sides.

Sertorius then went to Etruria (central Italy) and raised a new army. Many people there were afraid of Sulla. In 82 BC, Marius's son, Gaius Marius the Younger, became consul at a very young age. Sertorius disagreed with this, but his opinion was ignored. Sertorius saw that the leaders fighting Sulla were not doing well. He believed they would be defeated.

Governor of Hispania and Fugitive

By late 83 or early 82 BC, Sertorius was sent to Hispania as a proconsul, a powerful governor. He marched through the Pyrenees. A mountain tribe demanded money to let his army pass. His companions were angry, but Sertorius paid them. He said he was buying time, which was very valuable.

The current governor of Hispania did not recognize Sertorius's authority. But Sertorius had an army and took control. He convinced local leaders to accept him. He lowered taxes to gain the people's support. He then started building ships and gathering soldiers. He knew Sulla would send armies after him.

Sertorius soon learned that Sulla had won the civil war in Italy. He also found out that he was one of the first people Sulla had declared an enemy. By 81 BC, Sertorius's Hispania became a top target for Sulla's government. Sulla sent a large army under Gaius Annius Luscus. Annius's forces broke through the Pyrenees after Sertorius's officer, Salinator, was killed.

Sertorius was outnumbered. He decided to leave Hispania. He sailed to Mauritania (North Africa) with 3,000 loyal followers. He tried to attack some coastal cities but was driven away. He then joined some Cilician pirates and took an island called Pityussa. Sulla's forces sent a fleet and drove them out.

Sertorius heard about the "Isles of the Blessed," a mythical place. He was interested in these islands for his own political goals. His pirate allies left him and went to Africa. Sertorius followed them and defeated a local ruler and the pirates. He gained control of Tingis.

News of Sertorius's success spread. The people of Hispania, especially the Lusitanians in the west, admired him. Roman generals had been harsh to them, taking high taxes and fighting tribes for plunder. The Lusitanians asked Sertorius to be their war leader. They hoped he would bring back his milder rule.

Sertorius was sad when he learned his mother had died in Italy. He was so upset he stayed in his tent for a week. But with the help of his friends, he decided to accept the Lusitanian offer. He prepared his army to return to Hispania.

The Sertorian War Begins

Sertorius crossed the Strait of Gibraltar in 80 BC. He landed near the Pillars of Hercules. A small Roman fleet tried to stop him but failed. The Lusitanians joined him, and he marched against Lucius Fufidius, the Roman governor. Sertorius defeated Fufidius at the Battle of the Baetis River. This helped him take control of the province.

Sertorius was brave and a good speaker. He impressed the local warriors. He organized them into an army, mixing them with his Roman soldiers. People called him the "new Hannibal" because he was missing an eye, like Hannibal, and was a brilliant general. He often defeated armies much larger than his own. Many Roman exiles and Italian refugees joined him. His power grew quickly after these victories.

From 79 to 77 BC, Sertorius's main enemy was Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius, an experienced Roman general. Sertorius used clever guerrilla warfare tactics. He moved quickly and constantly, outsmarting Metellus. Sertorius also defeated and killed Metellus's officer, Lucius Thorius Balbus.

Metellus's attacks in 79 BC failed. Sertorius gained control of both Spanish provinces. From 78 BC, Metellus tried to attack cities loyal to Sertorius. But Sertorius always stopped him. When Metellus tried to besiege Lacobriga, Sertorius supplied the city and ambushed Metellus's soldiers, forcing him to leave. In 77 BC, Sertorius focused on bringing more Iberian tribes under his control.

Sertorius trained the Iberians to fight like Roman soldiers. He encouraged them to decorate their weapons with gold and silver. Many native Iberians swore loyalty to him. They served as his bodyguards and would even take their own lives if he died.

Sertorius famously taught his soldiers a lesson about tactics. The Lusitanians wanted to fight the Roman legions head-on. Sertorius knew this would be a disaster. He showed them two horses, one strong and one weak. An old man pulled hairs from the strong horse's tail one by one. A strong youth tried to pull all the hairs from the weak horse's tail at once. The old man succeeded, but the youth failed. Sertorius explained that the Roman army was like the horse's tail. It could be defeated piece by piece, but not all at once.

Sertorius was strict with his soldiers but kind to the people. He made their taxes and burdens as light as possible. This helped him keep the support of the native Iberians. His most famous strategy was his white fawn. He claimed it was a gift from a native and that it communicated advice from the goddess Diana.

The Iberian people were very impressed by the fawn. They saw Sertorius as a leader guided by the gods. Sertorius would hide information from military reports. Then he would claim Diana told him the information in his dreams. He would act on it, making people believe his story. White animals were seen as having special powers among some ancient peoples.

Battles and Alliances

In the summer of 77 BC, the Roman Senate realized they needed more power to defeat Sertorius. They gave a special command to Pompey to crush the rebellion. Soon after, in late 77 or early 76 BC, Marcus Perperna Veiento joined Sertorius. Perperna brought many Roman nobles and a large Roman-style army. With this army, Sertorius could now fight the Roman generals in open battles.

Sertorius successfully besieged the city of Contrebia. He then met with Iberian tribal leaders. He thanked them for their help and discussed the war's progress.

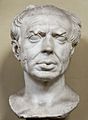

By 76 BC, Pompey had a large army of about 30,000 soldiers. His arrival in Hispania caused some unrest against Sertorius. But Sertorius paid close attention to Pompey's movements. He called Pompey "Sulla's pupil" with some contempt. Sertorius was at the peak of his power. Most of Iberia was under his control.

Sertorius moved south and blocked the city of Lauron. This city had recently allied with Pompey. Sertorius besieged Lauron, hoping to draw Pompey away. Pompey marched to Lauron, but Sertorius had set a trap.

Sertorius completely outsmarted Pompey at the Battle of Lauron. He kept Pompey from moving by threatening an attack from behind. He then killed Pompey's foraging parties and a Roman legion sent to help them. Pompey could do nothing as a third of his army was destroyed. Sertorius let the people of Lauron go and burned their city. He then punished a Roman group that tried to rob the Lauronians.

Sertorius was also a great leader in government. He wanted to build a stable government in Hispania. He created a Senate with 300 members, including Romans and top Iberian leaders. He also had an Iberian bodyguard. For the children of important native families, he started a school in Osca, his capital city. They learned Roman ways and dressed like Roman youths. Sertorius held exams and gave prizes. He promised the children and their fathers that they would hold important positions in the future.

Later Battles and Decline

In 75 BC, Pompey defeated Perperna and another officer at the Battle of Valentia. Sertorius left his command against Metellus and marched to meet Pompey. Metellus defeated another of Sertorius's officers. Sertorius then fought Pompey at the Battle of Sucro.

Both generals led their right flanks. Sertorius faced Lucius Afranius. When Sertorius saw his left wing failing, he inspired them and led a strong counterattack. He almost captured Pompey. Afranius, however, had broken Sertorius's right wing and was robbing their camp. Sertorius rode over and forced Afranius to leave. Both armies prepared to fight again the next day. But Sertorius heard that Metellus had defeated Perperna and was coming to help Pompey. Sertorius did not want to fight two larger armies. He left, saying, "If the old woman [Metellus] had not appeared, I would have thrashed the boy [Pompey] and sent him back to Rome."

Sertorius also talked with the powerful King Mithridates VI of Pontus. Mithridates wanted Rome to confirm his control over some kingdoms. Sertorius's Senate agreed that Mithridates could have some kingdoms that were not Roman. But they would not let him have Asia, which was a Roman province. Mithridates accepted these terms and sent Sertorius a lot of gold and ships.

Later, Sertorius was forced by his native troops to fight Metellus and Pompey. This was likely at the Battle of Saguntum. This was the last big battle Sertorius fought. It was a fierce fight that lasted all day. Both sides suffered heavy losses.

After the battle, Sertorius sent his army away, telling them to regroup later. This was common for Sertorius. He would often disappear and then reappear with a new army.

After the battle, Sertorius went back to guerrilla warfare. He had lost the heavy soldiers Perperna brought, which had allowed him to fight the Roman legions head-on. He retreated to a strong mountain fortress called Clunia. Pompey and Metellus tried to besiege him there. Sertorius made many attacks from the fortress, causing heavy losses to the Romans. Sertorius tricked them into thinking he would stay besieged. Then he broke through their lines, joined a new army, and continued the war.

The two Roman generals had followed Sertorius into difficult lands. Sertorius regained the advantage. He continued his guerrilla attacks. He eventually forced Metellus and Pompey to leave the area for the winter because they ran out of supplies. Pompey wrote to the Senate in Rome, asking for more soldiers and money. He said that without them, he and Metellus would be driven out of Hispania. The Senate sent more men and money.

With these new forces, Pompey and Metellus gained the upper hand in 74–73 BC. They slowly wore down Sertorius's rebellion. Sertorius did not have enough men for open combat, but he kept harassing them with guerrilla attacks. Many of his soldiers started leaving him and joining the Roman generals. Sertorius responded with harsh punishments. He won some small victories, but it was clear he could not win the war completely.

Sertorius was also in contact with the Cilician Pirates and the rebelling slaves of Spartacus in Italy. But his own Roman officers and some Iberian leaders grew jealous and afraid. A plot against him began to form.

Conspiracy and Death

Metellus had offered a huge reward to anyone who killed Sertorius. This made Sertorius very paranoid. He started to distrust his Roman followers. He even replaced his Roman bodyguards with Spanish ones. This made his Roman followers very unhappy. From late 74 BC, Sertorius became harsh and cruel to his officers.

The Roman nobles and senators who were with Sertorius were very unhappy. They were jealous of his power and tired of his paranoia and cruelty. They could see that victory was impossible. Perperna wanted to take Sertorius's place. He encouraged the jealousy among Sertorius's top Roman officers.

The conspirators started causing trouble for Sertorius. They oppressed the local Iberian tribes in his name. This caused the tribes to rebel. Sertorius did not know who was causing the problems. He punished many of the Oscan schoolchildren, even selling them into slavery, because of these native revolts.

One of the conspirators, Manlius, told his lover about the plot. This man then told another conspirator, Aufidius, who told Perperna. Perperna decided to act. He told Sertorius about a fake victory over the Roman generals. Sertorius was very happy. Perperna suggested a banquet to celebrate. He convinced Sertorius to attend, which would separate him from his bodyguards.

The banquet took place in Osca, Sertorius's capital. Many of Sertorius's top officers were part of the plot, including Perperna himself. Sertorius's loyal Spanish bodyguards were kept outside.

Normally, Sertorius's feasts were very proper. But this one was designed to upset him. Sertorius was disgusted and tried to ignore them. Perperna gave the signal by dropping his cup. The conspirators attacked. One man, Antonius, slashed at Sertorius. Sertorius tried to fight back, but Antonius held him down. The others rushed in and killed him.

Aftermath and Legacy

After Sertorius's death, some of his Iberian allies made peace with Pompey or Metellus. Most simply went home. The Lusitanians, who were very loyal to Sertorius, were furious about his assassination. What happened to Sertorius's white fawn and his body is not known.

Perperna took control of the rebel army, but it quickly fell apart. He used harsh methods to keep power, even executing his own nephew. Sertorius's will named Perperna as his main heir. This made Perperna look even worse. He had killed the man who gave him safety and was his main supporter. People remembered Sertorius's good qualities and forgot his recent harshness.

After Sertorius died, his independent "Roman" Republic crumbled. Pompey and Metellus easily defeated Perperna's army. Pompey killed the rest of Sertorius's assassins and top Roman officers. Some escaped to Africa.

Several cities loyal to Sertorius refused to surrender. Pompey stayed in Hispania for some years to conquer these remaining strongholds. When Pompey returned to Rome in 71 BC, he put up a monument. It said he had conquered over eight hundred towns. But it did not mention Sertorius.

Years later, during Julius Caesar's wars in Gaul, his officer Publius Licinius Crassus fought against some Gauls. These Gauls were helped by Iberians from Hispania. These Iberians were veterans who had fought with Sertorius. They had learned Roman military tactics from him. They were very skilled at fighting Romans. Crassus eventually defeated them.

Military Skills and Character

Ancient writers generally agree that Sertorius was a great military leader. They noted his skill in warfare. Some believed that if Sertorius had lived longer, the war would not have ended so quickly.

Sertorius was very good at guerrilla warfare, which was unusual for a Roman. Some experts praise his tactics but criticize his cautious strategy. They believe this led to his eventual defeat.

During Sulla's time, Sertorius was greatly feared. His war was not seen as easy to win. Some modern historians believe Sertorius was a traitor to Rome for fighting against the Senate and working with native tribes. Others believe he was a true patriot fighting for a lost cause. Ancient historians describe Sertorius as becoming cruel and harsh later in the war. But others admired his great courage.

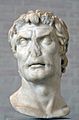

No statues or coins showing Sertorius have been found. There is no evidence that Sertorius had any children.

Political Impact

Sertorius's true reasons for fighting are not fully known. But evidence suggests he saw himself fighting for the survival of those who had lost everything after Sulla's victory. Sertorius himself often tried to make peace with Metellus and Pompey. He said he would rather live in Rome as a humble citizen than be a supreme ruler in exile. This desire for peace might explain his cautious strategy.

Modern historians often describe Sertorius's war in terms of its impact on the Roman state and on Pompey's career. Pompey's unusual career began because of the civil wars. Sertorius's strong military threat forced the Senate to give Pompey extraordinary power. This weakened the Senate's control over the Roman army.

For the Roman exiles, Sertorius offered a chance to return to their homes and political lives in Rome. Sertorius's war is seen as a result of Sulla's harsh punishments. His death marked the end of the civil wars started by Sulla.

Many writers describe Sertorius's life as a tragedy. One writer said he was more self-controlled than Philip, more loyal to friends than Antigonus, and kinder to enemies than Hannibal. He was wise and smart but had bad luck. Another writer said his talents were wasted in a struggle he did not want, could not win, and could not escape.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Quinto Sertorio para niños

In Spanish: Quinto Sertorio para niños

- Sertoria gens

- Sertorian War

- Timeline of Portuguese history

- Gaius Julius Civilis