Publius Clodius Pulcher facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Publius Clodius Pulcher

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Born | c. 92 BC | ||||||||

| Died | 18 January 52 BC Near Bovillae

|

||||||||

| Cause of death | Murdered | ||||||||

| Office |

|

||||||||

| Spouse(s) | Fulvia | ||||||||

| Children | Publius and Claudia | ||||||||

| Parent(s) |

|

||||||||

| Relatives |

|

||||||||

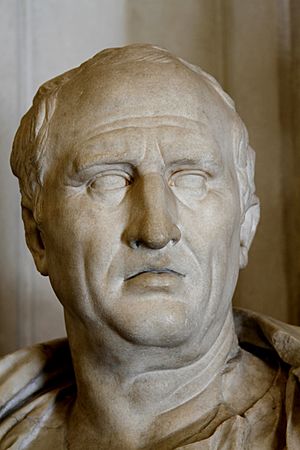

Publius Clodius Pulcher (born around 92 BC – died January 18, 52 BC) was a powerful Roman politician. He was known for being a "demagogue," which means he was a leader who gained power by appealing to people's emotions and prejudices, often using strong speeches.

Clodius was a major rival of the famous speaker Cicero. During his time as a plebeian tribune in 58 BC, Clodius made the Roman grain dole much bigger. This meant free food for many citizens. He also managed to get Cicero sent away from Rome. Clodius was a leader of political groups in the 50s BC. His way of doing politics involved using his connections with powerful families and gaining support from the poor people of Rome. This made him a very important figure in Roman politics.

Clodius was born into the very old and influential gens Claudia family. Early in his career, he was involved in a religious scandal. This event led to his rivalry with Cicero. To become eligible for the plebeian tribunate, he changed his status to become a plebeian. He successfully became a tribune in 58 BC. He then passed several important laws. These laws brought back private clubs and groups called collegia. He also made the grain dole free for citizens. To pay for this, he arranged for Cyprus to become part of the Roman Empire. Clodius also made it harder for censors to remove senators from the senate. Finally, he passed a law that exiled Cicero from Rome. This was because Cicero had executed conspirators without a trial during the Catilinarian conspiracy.

Later, in 56 BC, when he was a curule aedile, Clodius had a big feud with Titus Annius Milo. Milo controlled his own groups of followers. Clodius and his family eventually made peace with Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus, forming a political alliance. A few years later, in 52 BC, political violence was high. Clodius was campaigning to become a praetor. He and Milo met on the via Appia road outside Rome. Clodius was killed during this encounter. His body was brought back to Rome and taken to the Forum. It was then burned in the senate house, which caused the building to catch fire and be destroyed.

Clodius often used his influence over groups of people in Rome. These groups sometimes used violence to achieve his political goals. However, his family connections and noble background also made him a valuable ally to many powerful Romans. These included Caesar, Cato, and Pompey. Older ideas suggested that Clodius was just a tool for powerful leaders like Caesar or Pompey. But today, historians see him as an independent politician who looked for opportunities to gain power.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Publius Clodius Pulcher was born into the ancient and noble gens Claudia family. His family line could be traced back to the early days of the Roman Republic. His ancestor, Attus Clausus, was a consul in 495 BC. The branch of the family Clodius belonged to, the Claudii Pulchri, came from Appius Claudius Caecus, a censor in 312 BC.

Clodius' father, Appius Claudius Pulcher, was a consul in 79 BC. He supported the Roman general Sulla. Clodius' father died in 77 BC, leaving behind three sons. Publius Clodius was the youngest. His older brothers were Appius and Gaius. Clodius also had three sisters, all named Clodia. One sister married Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer. Another married Lucius Licinius Lucullus. The third married Quintus Marcius Rex.

Early Career and Military Service

Clodius first appears in historical records while serving under his brother-in-law, Lucullus. This was during the Third Mithridatic War in 68 BC. He may have been a military officer, or legate. During this time, he encouraged soldiers to rebel. The next year, he served under Quintus Marcius Rex, another brother-in-law. Clodius was in charge of the fleet but was defeated and captured by pirates. He was later freed. After his release, he continued to serve in the military. His military career was not very successful. However, Romans often believed that noblemen were naturally good at military matters.

In 65 BC, Clodius returned to Rome. He tried to prosecute Lucius Sergius Catilina, but it was unsuccessful. Later, Clodius' enemy Cicero claimed that Clodius worked with Catiline to make the prosecution fail. However, most historians do not believe this. Catiline was likely found innocent because of bribery and his powerful allies.

Clodius may have been a military tribune in 64 BC. He also worked for Lucius Licinius Murena, a praetor, in Gaul. In 63 BC, Clodius helped Murena in his campaign to become consul. He likely helped distribute money to voters. There is no evidence that Clodius was involved in the Catilinarian conspiracy that year. Clodius probably opposed the conspirators.

The Bona Dea Scandal

In 62 BC, Clodius successfully ran for quaestorship. Before he took office, he was involved in a major scandal. In December 62 BC, he secretly entered the house of Julius Caesar, the pontifex maximus. This was during the secret rites of the goddess Bona Dea, which only women were allowed to attend. His reasons for doing this are not clear.

The Roman Senate eventually decided that Clodius' actions were sacrilegious. They set up a special court to try him. Clodius had allies, including a consul and a tribune. They argued that the trial was unfair. Clodius and his supporters even used a mob to disrupt the process. After much debate, a new law was passed for the trial. The jury was chosen by lot, not by the praetor.

At the trial, Clodius was accused of sacrilege. Julius Caesar's mother and sister testified that Clodius was present. Clodius claimed he was not in Rome at the time. However, Cicero testified that Clodius was indeed in Rome. This testimony made Clodius and Cicero bitter enemies. The Senate ordered protection for the jurors because of fears of violence. Despite this, the jury voted 31 to 25 to acquit Clodius. Many believed the decision was due to bribery. Cicero later claimed Clodius spent almost all his money on bribes. Julius Caesar divorced his wife, Pompeia, after the trial. This helped him avoid further trouble.

Becoming a Plebeian

The Bona Dea scandal hurt Clodius' political future. He wanted to become a plebeian so he could run for plebeian tribune. Patricians were not allowed to hold this office. He tried several ways to change his status.

First, his allies tried to pass a law to make him a plebeian. But other tribunes stopped these bills. Then, Clodius tried a religious ceremony called sacrorum detestatio. He thought this would make him a plebeian. However, the consul and the Senate disagreed.

Finally, in 59 BC, during the consulship of Gaius Julius Caesar and Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus, Clodius found an opportunity. After Cicero gave a speech criticizing Caesar and Pompey, they decided to help Clodius. They arranged for Clodius to be adopted by a plebeian named Publius Fonteius. Fonteius was even younger than Clodius! After this, Clodius became a plebeian. He then ran for plebeian tribune.

After his adoption, Clodius initially supported Caesar and Pompey. He spoke in favor of a law that gave Caesar his command in Gaul. However, when Clodius did not get the appointments he expected, he broke away from them. He began to oppose Caesar, taking advantage of their unpopularity. Even Cicero was happy to see Clodius oppose Caesar. Clodius also started to move against Cicero, but Pompey, who was still friendly with Clodius, helped Cicero for a while.

Clodius as Tribune

Clodius easily won the election for tribune in the summer of 59 BC. His term began in December. Before his term started, Pompey and Cicero had a falling out. Also, two consuls who supported Caesar and Pompey were elected for 58 BC. Clodius then changed his strategy again. He supported Caesar and Pompey by stopping Bibulus from giving his usual speech when leaving the consulship.

Clodius' New Laws

On his first day as tribune, December 10, 59 BC, Clodius announced four major laws. These laws had been planned for a long time. They were meant to gain him popular support and the support of many senators.

Clubs and Guilds Law

The Senate had banned many clubs and guilds, called collegia. These included professional groups and religious organizations. Clodius' law brought these groups back. They were officially recognized by the state. Reviving these clubs allowed Clodius to gain influence and connections with the common people of Rome.

Free Grain Law

Clodius also greatly expanded the grain dole. Before, grain was sold at a low price. Now, five measures of grain would be given for free to Roman citizens. This was a huge cost for the state. The clubs Clodius revived may have helped distribute this grain. This free food made Clodius very popular with the urban poor. To pay for it, the Senate had to mint special coins. Clodius also raised money by annexing Cyprus.

Law on Omens

The previous year, Caesar's fellow consul, Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus, tried to stop Caesar's laws. He did this by saying he was observing bad omens from his house. Clodius' law made it clear that such announcements had to be made in person to be valid. This stopped officials from blocking government actions from home.

Law on Censors

Roman censors had the power to remove senators from the Senate. Clodius' law required both censors to agree to remove someone. They also had to give a reason and allow the senator to speak in their defense. This law was popular among many senators. It protected them from being unfairly removed.

Cicero's Exile

At the start of 58 BC, Cicero announced his opposition to Clodius. He found an ally in another tribune, Lucius Ninnius Quadratus. Clodius made a deal with Cicero: if Cicero would stop Ninnius, Clodius would not pursue his feud with Cicero. This deal allowed Clodius to pass his four laws on January 4, 58 BC.

Clodius' popular support became clear when he disrupted a trial. He gathered a mob that overturned benches and smashed voting urns. Clodius quickly learned to use these mobs. In February, Clodius proposed two more bills. One assigned provinces to the current consuls. The other, the lex Clodia de capite civis Romani, was clearly aimed at Cicero. This law said that any magistrate who killed a citizen without trial, and senators who advised it, should be exiled. This referred to Cicero's actions during the Catilinarian conspiracy.

Cicero and his ally Ninnius wore mourning clothes to protest. The Senate also decreed this. However, the consuls ignored the decree and supported Clodius' bill. Clodius used his mobs to attack Cicero and disrupt his rallies. Clodius then made a clever move. He assigned the annexation of Cyprus to Marcus Porcius Cato. Cato had strongly supported executing the conspirators in 63 BC. This move isolated Cicero. Cicero refused Caesar's offer of immunity. He then left Rome and went into exile. Clodius immediately passed another law, the lex Clodia de exsilio Ciceronis. This law officially exiled Cicero, confiscated his house, and banned the Senate or people from recalling him.

Opposing Pompey

Clodius' success with his laws gave him huge political power. He began to act as an independent political force. He then turned against Pompey. Clodius tried to undo some of Pompey's arrangements in the East. He also kidnapped a prince who was a hostage of Pompey. This led to a bloody clash between Clodius' and Pompey's followers. Pompey and Clodius then became political enemies.

Clodius' gangs even attacked a consul, destroying his symbols of office. This was too much for the political class. Another tribune tried to pass a bill to recall Cicero from exile. The Senate supported it, but it was stopped by a veto. However, a movement to bring Cicero back grew. Pompey eventually led this effort.

Later in the year, Clodius also supported Cato's group against Caesar's laws. He argued that Caesar's laws were not valid for religious reasons. This was likely an attempt to get Cato's group to help him prevent Cicero's return. There were also rumors that Clodius ordered an assassination attempt on Pompey. Pompey became very paranoid and stayed in his villa. Clodius' gangs then threatened the villa. Despite Clodius' actions, the opposition to him grew. Eight of the ten tribunes tried to recall Cicero, but it was vetoed again. The opposition decided to wait until Clodius' term as tribune ended in December.

Changing Alliances

Efforts to Recall Cicero

On December 10, 58 BC, Clodius became a private citizen again. Pompey's allies in the tribunate immediately proposed a bill to recall Cicero. Most tribunes supported it. In January 57 BC, the new consuls also supported Cicero's return. However, one of Clodius' allies, a tribune named Sextus Atilius Serranus Gavianus, used his veto power. This stopped the bill throughout January.

When the bill to lift Cicero's exile came to a vote on January 23, 57 BC, two tribunes tried to prevent a veto. Clodius' gangs, strengthened by gladiators, drove them from the Forum. Cicero's brother barely escaped the fighting. Another tribune, Titus Annius Milo, had the gladiators arrested. But Serranus freed them. From this point, Milo and Clodius became fierce rivals.

The political leaders united against Clodius' violence. Milo tried to prosecute Clodius for public violence. But Clodius' allies in office made it impossible for him to be tried. Clodius' advantage in street fights was lost when more violence broke out. Many politicians began to arm their own groups. Pompey supported Cicero and gathered support from all over Italy. By summer, most of Italy supported Cicero's return. Clodius' only remaining tactic was to cause food riots. When the Senate voted on lifting Cicero's exile in July, the measure passed 416 to 1. Clodius was the only one against it. His allies then became unwilling to veto the bill.

On August 4, 57 BC, Clodius tried to disrupt a public meeting. But he failed. The bill to recall Cicero passed later that day. Many of Cicero's supporters came from all over Italy to vote. Pompey's victory was complete. The Senate then gave Pompey a special command to bring food to Rome to stop the riots. Clodius and Cicero again clashed over Cicero's house. Clodius had turned it into a shrine to the goddess Libertas. Cicero successfully argued that Clodius' law was invalid. Clodius then tried to disrupt construction on Cicero's house and harass Cicero and Milo. However, Clodius still had support from some important men. The ongoing political struggle over the Egyptian command would soon bring Clodius back into favor.

Egypt and Political Comeback

Ptolemy XII Auletes, the king of Egypt, was removed from his throne in 57 BC. He came to Rome to ask for help to get it back. Rome had political and economic reasons to help him. The Senate decided that the consul Spinther should restore Ptolemy. Spinther left to take up his province. However, debates continued in Rome about who should lead the Roman response. Pompey's name was suggested. Pompey's enemies in the Senate then found Clodius' anti-Pompeian actions useful again.

Clodius' enemies wanted to prosecute him for public violence. They knew he would soon become immune from prosecution if he won election as aedile. Milo tried to delay elections to prosecute Clodius. However, Clodius' allies in office made it impossible. The issue of trying Clodius was eventually dropped. The Senate approved elections that made Clodius an aedile in 56 BC.

As Aedile

Clodius was elected aedile on January 20, 56 BC. He was elected first because of his popularity. Many expected him to spend a lot of money, but his funds seemed low. He only put on the usual games and public works.

The early months of 56 BC were again focused on the Egyptian command. A religious sign occurred when lightning hit a statue. Clodius, as a priest, helped interpret this omen. The priests said it warned against helping the king of Egypt with a large army. This meant neither Pompey nor Spinther could gain military glory from it.

Clodius, as aedile, also prosecuted Milo for public violence. Cicero, Marcellus, and Pompey defended Milo. When Pompey spoke, the trial became chaotic. Clodius' crowd demanded that Crassus go to Alexandria instead of Pompey. The trial was then stopped due to violence. The Senate blamed Milo and Pompey for the disorder. This led Pompey to give up his plan for the Egyptian expedition.

In the spring of 56 BC, Clodius held the Megalensian games. Food riots continued, which embarrassed Pompey. However, Clodius' family and the powerful leaders Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus made peace. This led to a marriage between Pompey's son and Clodius' niece. Attacks on Cicero did not stop. Clodius used his religious authority to blame Cicero for divine displeasure. Cicero responded by blaming Clodius. Cicero, with Milo's support, removed the tablets that recorded Clodius' laws. However, few senators supported Cicero's claim that Clodius' adoption and laws were invalid.

The year ended with Gaius Cato, supported by Clodius, stopping consular elections for months. This was a plan to make Pompey and Crassus consuls in 55 BC. Clodius' gangs protected Gaius Cato. Pompey and Crassus used violence to win the elections. Clodius likely benefited from this new alliance. He received funding for an embassy to the East. This allowed him to visit eastern provinces and clients, likely to replenish his money. Clodius was probably away from Rome for the rest of 55 BC.

Clodius' Death

Campaign for Praetor

Clodius returned to Rome in 54 BC. He was likely seeking to become a praetor in 53 BC. His success seemed certain. His campaign included a promise to give freedmen more political power by moving them into rural tribes.

Clodius was part of Pompey's effort to stop Titus Annius Milo from winning the consular elections for 52 BC. Clodius supported the other two candidates. Clodius and Milo immediately began fighting in the streets with their gangs. Clodius tried to ambush Milo. Milo fought back against Clodius' attempts to seize voting areas. The street fighting was so chaotic that elections could not be held in 53 BC. Clodius' campaign for praetor continued into the new year. As part of his campaign, he visited Aricia, a town south of Rome.

The Fatal Encounter with Milo

The main source for Clodius' death is a commentary on Cicero's speech Pro Milone. Cicero's speech itself is not a completely truthful account. The events happened like this: Clodius was traveling back from Aricia. He and Milo met on the via Appia road near Clodius' villa in Bovillae. This was around 1:30 pm on January 18, 52 BC. Milo was traveling to install a priest. Both men had armed groups with them. Clodius' group was smaller, about 26 men compared to Milo's 300.

After the two groups passed each other, a fight broke out. Clodius was hit in the shoulder with a javelin. Clodius' men were defeated in the fight. Clodius was carried to a roadside inn. But when Milo heard Clodius was wounded, he ordered his officer to kill Clodius. Clodius was dragged out of the inn and killed. A senator found the body and sent it to Rome. It arrived around 4:30 pm and was brought before Clodius' wife, Fulvia.

The story of Clodius' death was immediately twisted by different political groups. Milo and his allies claimed that Clodius had planned to ambush Milo. They said the fight was self-defense. This was the main story Milo's supporters spread. However, others, like Metellus Scipio, said Milo had planned the murder. Many people felt that Milo was justified in killing Clodius, not just for self-defense, but because it was good for Rome.

Funeral and Aftermath

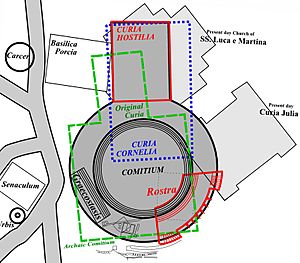

The next morning, January 19, two tribunes who supported Clodius held a public meeting. They strongly criticized Milo for the murder. The crowd, led by Sextus Cloelius, took Clodius' body into the curia Hostilia. There, they burned his body using the Senate's furniture and records. The fire spread and destroyed the building and a nearby basilica. Milo had fled the city for safety. But when he heard about the destruction of the Senate house, he returned. The burning of this important building turned public opinion against Clodius' supporters. Milo continued his campaign to become consul.

Rome fell into chaos. The Senate passed an emergency decree. This ordered Pompey to bring soldiers into the city to restore order. After many attempts to hold elections failed, Cato and Bibulus suggested a compromise. They wanted Pompey to be elected as the only consul. This would prevent Milo from winning. Pompey was then elected consul.

Pompey immediately passed laws to create a special court to try public violence cases. Milo was accused by Clodius' nephews. The Senate passed a resolution condemning the murder. Milo was found guilty by the jury and went into exile. Milo's officer, who actually killed Clodius, was acquitted. Cloelius, who suggested burning Clodius' body in the curia, was convicted. The tribunes who helped were also convicted after their terms ended.

Clodius' Legacy

After Clodius' death, his political style influenced later politicians. He combined connections with noble families with support from the poorer people of Rome. For example, Publius Cornelius Dolabella changed his status to become a plebeian. He then became a tribune and proposed canceling all debts. He even put up statues of Clodius.

Clodius was not the first or last to use political violence in Rome. However, his use of mobs to disrupt or support political actions was notable. The grain dole law that Clodius passed continued to exist even after the Roman Republic fell. It lasted throughout the Roman Empire. Roman emperors later used similar ideas, like building public monuments and helping the poor, which reflected some of Clodius' political style.

Clodius' reputation in ancient and modern history is mostly negative. This is because many sources rely on Cicero's harsh criticisms of him. Modern historians have called him names like "a petty gangster" or "an irresponsible demagogue." For a long time, he was seen as a tool of Caesar or an enemy of the Senate. However, since 1966, scholars have started to see Clodius as an independent politician. They believe he tried to use different groups in the late Republic to gain power for himself. This view is now widely accepted.

Tables and Diagrams

Offices Held

| Year (BC) | Office | Note |

|---|---|---|

| 68 | Legate (possibly), Syria | Served under Lucullus |

| 67 | Legate (possibly), Cilicia | Served under Quintus Rex |

| 64 | Military tribune (possibly) | Served under Murena |

| 61–60 | Quaestor, Sicily | |

| 60–52 | Quindecimvir sacris faciundis | A priest who oversaw sacred books |

| 58 | Plebeian tribune | A representative of the common people |

| 56 | Curule aedile | An official in charge of public works and games |

Immediate Family

- Appius Claudius Pulcher (consul 79 BC)

- Appius Claudius Pulcher (consul 54 BC)

- Claudia, wife of Pompey

- Claudia, wife of Marcus Junius Brutus

- Gaius Claudius Pulcher

- Appius Claudius Pulcher (consul 38 BC)

- Marcus Valerius Messalla Barbatus Appianus

- Gaius Claudius Pulcher

- Appius Claudius Pulcher (consul 38 BC)

- Clodia Tertia, wife of Quintus Marcius Rex

- Clodia, wife of Metellus Celer

- Publius Clodius Pulcher

- Claudia, wife of Octavian

- Publius Clodius Pulcher

- Clodia, wife of Lucullus

- Licinia

- Appius Claudius Pulcher (consul 54 BC)

Family Tree

| ignota (2) (Fonteia?) married c. 138 |

Ap. Claudius Pulcher cos. 143, cens. 136 (c. 186–130) |

(1) Antistia (Vetorum) married c. 164 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Claudia Vestal born c. 163 |

Claudia minor Gracchi born c. 161 |

Ap. Pulcher (c. 159–135/1) |

Claudia Tertia born c. 157 |

Q. Philippus mint IIIvir c. 129 born 160s, married c. 143 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C. Pulcher (c. 136–92) cos. 92 |

Ap. Pulcher (c. 130–76) cos. 79 |

Ignota | x | L. Philippus (c. 141–c. 74) cos. 91 |

Q. Philippus (c. 143–c. 105) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Claudiae maior et minor (born 100–99) |

Claudia Tertia Q. Regis (born c. 98) |

Ap. Pulcher (97–49) cos. 54, augur, cens. 50 |

C. Pulcher (96–c. 30s) pr. 56 |

Claudia Quarta Q. Metelli Celeris (born c. 94) |

P. Clodius Pulcher tr. pl. 58 (93–53) |

Claudia Quinta L. Luculli (born 92/90) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Claudia maior M. Bruti |

Claudia minor ignoti |

Claudia C. Caesaris (born c. 56) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

In Spanish: Clodio para niños

In Spanish: Clodio para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |