Catiline facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Catiline

|

|

|---|---|

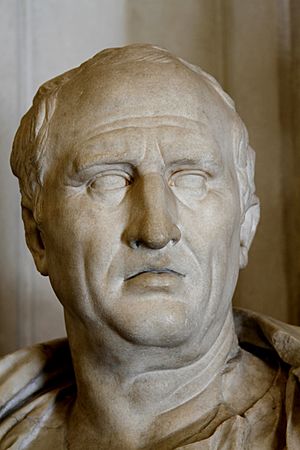

A painting of Catiline in Palazzo Madama

|

|

| Born |

Lucius Sergius Catilina

c. 108 BC |

| Died | early January 62 BC |

| Nationality | Roman |

| Occupation | General and politician |

| Known for | Catilinarian conspiracy |

| Parents |

|

Lucius Sergius Catilina (around 108 BC – January 62 BC), known as Catiline, was a Roman politician and soldier. He is most famous for starting the Catilinarian conspiracy. This was a failed attempt to take control of the Roman government by force in 63 BC.

Catiline came from an old, important Roman family. He joined Sulla during a civil war and became rich during that time. In the early 60s BC, he served as a praetor (a high-ranking official) and then as governor of Africa (67 – 66 BC). When he returned to Rome, he tried to become a consul (one of the two highest officials), but he was not allowed to run. He then faced legal problems about his time as governor and his actions during Sulla's rule.

With help from powerful friends, he was found innocent of all charges. He then tried to become consul two more times, in 64 and 63 BC. After losing these elections, he planned a secret uprising to take the consulship by force. He gathered poor farmers, former soldiers, and other senators whose careers had stopped.

In October 63 BC, Crassus told Cicero, one of the consuls, about the plot. This plan included armed uprisings in Etruria. By November, there was clear proof that Catiline was involved. Once discovered, he left Rome to join his rebellion. In early January 62 BC, Catiline led his rebel army near Pistoria (modern Pistoia). He fought a battle against the Roman army. Catiline was killed, and his army was completely defeated.

After his death, Catiline's name became a symbol for failed and disloyal rebellions. The writer Sallust wrote a book about the conspiracy, Bellum Catilinae. In it, he described Catiline as a sign of the Roman Republic's problems.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Family Background

Catiline belonged to an old and important Roman family called the Sergia gens. They believed they were related to Sergestus, a Trojan friend of Aeneas. Even though his family was old, they had not held the consulship for a very long time. The last time was in 429 BC.

We do not know the exact year Catiline was born. Based on the jobs he held, he was likely born by 108 BC. His parents were Lucius Sergius Silus and Belliena. His father was not rich compared to other noble families. Catiline's great-grandfather, Marcus Sergius Silus, was a praetor in 197 BC and was known for his bravery during the Second Punic War.

Early Career

During the Social War, Catiline served under Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo. Other famous Romans like Pompey and Cicero also served with him. His name is on an old bronze tablet, which shows he was part of Strabo's council.

Catiline married a woman named Gratidia. She was a niece of Gaius Marius, another important Roman figure. During Sulla's civil war in 82 BC, Catiline joined Sulla's side. He became very wealthy during this time. He likely bought properties for very low prices. By the end of Sulla's rule, Catiline was a rich man.

Catiline later faced accusations of serious crimes, but he was found innocent. His friend Catulus, who was likely the head of the court, helped him. Catiline felt he owed a lot to Catulus for this help.

Attempts to Become Consul

Catiline served as a praetor around 68 BC. After that, he was the governor of Africa for two years (67–66 BC).

Around the mid-60s BC, Catiline married Aurelia Orestilla. She was wealthy and beautiful. This was his second marriage. Some ancient writers said he married her only for her looks, which Romans thought was not good. Later, Cicero made some very strong accusations about Catiline's family life. However, historians today believe these were likely just political attacks by Cicero.

Elections of 66 BC and Legal Problems

When Catiline returned to Rome in 66 BC, people from Africa complained about how he had governed. Catiline tried to run for consul, but his request was turned down. This might have been because he was about to face a trial for corruption.

Later in 65 BC, Catiline was put on trial for corruption during his time as governor. Publius Clodius Pulcher led the prosecution. However, many powerful former consuls defended Catiline. The jury was made up of senators, knights, and other officials. The senators voted to find him guilty, but the other two groups voted for him to be innocent. So, Catiline was found innocent. Cicero thought about defending Catiline at this trial but decided not to.

Consular Elections of 64 BC

Catiline was allowed to run for consul in 64 BC. The other main candidates were Cicero and Gaius Antonius Hybrida. Catiline spent a lot of money on bribes. Cicero gave a speech attacking Catiline and Antonius. Antonius and Catiline were allies and tried to defeat Cicero. However, Cicero won the election with everyone's support. Antonius won the second consul spot, narrowly beating Catiline.

This was also the year that Gaius Julius Caesar was in charge of a court for murder cases. His actions, along with Cato the Younger's demands for repayment of loans, might have made voters less likely to support Catiline. After the elections, Catiline was again accused of murder during Sulla's time. He was found innocent once more, with several former consuls speaking in his defense.

Catilinarian Conspiracy

- Further information: Catilinarian conspiracy

Antonius, who had been Catiline's ally, decided to work with Cicero instead. He took a rich province in exchange for his cooperation. So, Antonius broke ties with Catiline early in 63 BC. At the start of 63 BC, there was no sign that Catiline was planning anything. However, he still hoped to become consul, which he felt was his right.

Consular Elections

The year 63 BC was not peaceful. Early in the year, a plan to give out land to the poor was proposed. This would have helped many people during tough economic times. But Cicero spoke against it, saying it would cause problems. This failure to help the poor likely pushed some people to support Catiline's plans.

That summer, Catiline ran for consul again in 63 BC. Cicero accepted his candidacy. Other main candidates were Decimus Junius Silanus and Lucius Licinius Murena. Cicero supported his friend Sulpicius, which hurt Catiline's chances. Before the elections, Cicero claimed Catiline was trying to gain support from the poor by promising to cancel all debts. At the election, Cicero wore armor and had bodyguards. This was to show that he believed Catiline was a threat. The election results made Decimus Junius Silanus and Lucius Licinius Murena the new consuls. After losing for the second time, Catiline seemed to run out of money and lost support from people like Crassus and Caesar.

Conspiracy

On October 18 or 19, Crassus and two other senators visited Cicero. They gave him anonymous letters warning that Catiline was planning to kill important politicians. Cicero called a meeting of the senate and had the letters read aloud. A few days later, news came that a former soldier, Gaius Manlius, had raised an army in Etruria. The senate quickly passed an emergency decree. This allowed the consuls to do whatever was needed to protect the state. When Manlius heard about this, he openly rebelled.

Some historians today think Manlius's rebellion might have been separate from Catiline's plans at first. They suggest Catiline only joined Manlius when he left Rome. However, ancient sources do not say this.

Catiline's reasons for conspiring were not just about money. His "wounded pride and fierce ambition" played a big part. Many senators who joined him had been removed from the senate or had their careers stopped. The men who joined Manlius's rebellion were mostly poor farmers who had lost their land and former soldiers looking for more wealth. These men came from different backgrounds and had different goals.

Flight from the City

While the consuls made central Italy stronger, there were also reports of slave revolts in the south. Two generals were sent to guard the northern and southern parts of Rome. Catiline stayed in Rome because there was no direct proof against him yet.

On November 6, Catiline held a secret meeting in Rome. He planned to join Manlius's army. Other conspirators were to start revolts elsewhere in Italy and set fires in Rome. Two conspirators were supposed to kill Cicero the next morning. Cicero later exaggerated Catiline's plan to burn the city to turn people against him. It is more likely that Catiline wanted fires to create confusion for his army.

The next day, November 7, the assassins found Cicero's house closed. Cicero then called the senate to the Temple of Jupiter Stator. He told them about the threat to his life and gave his famous "First Catilinarian" speech, attacking Catiline. Catiline, who was already planning to leave, offered to go into exile if the senate agreed. Cicero refused. Catiline then left Rome, saying he was going into voluntary exile to avoid a civil war. He sent a letter to his old friend Quintus Lutatius Catulus Capitolinus. In the letter, Catiline said he was an innocent person who was helping the less fortunate. He strongly denied that he was leaving because of debts.

He left Rome on the road to Massilia. But in Etruria, he went to a place where weapons were hidden. Then he went to Faesulae, where he met Manlius's forces. When he arrived, he declared himself consul and wore the clothes of a consul. When Rome heard this, the senate declared Catiline and Manlius public enemies. Antonius was sent with an army to defeat him.

Death

- Further information: Battle of Pistoria

In late November, Antonius's army approached from the south. Catiline moved his camp near the mountains but stayed close enough to the town to attack. Antonius avoided battle at first.

Catiline's fellow conspirators in Rome were caught by Cicero with help from some Gallic visitors. After a strong debate in the senate, they were executed without a trial on December 5. When Catiline's army heard about their deaths, many soldiers left. He was left with only about three thousand men. Catiline hoped to escape into Gaul. But his escape was blocked by Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer, who guarded the mountain passes.

Antonius kept his men calm near Faesulae. But after he got more soldiers in late December, he moved out. Catiline, seeing his escape blocked, turned south to face Antonius. They met at Pistoria, which is modern Pistoia. Catiline offered battle to Antonius's army, possibly on January 3, 62 BC.

On the day of the battle, Antonius gave command to Marcus Petreius, an experienced officer. Petreius broke through Catiline's army, forcing them to run. Catiline and his loyal supporters fought bravely. They were completely defeated. They were desperate men who did not want to survive their defeat.

Legacy

In Roman writings, Catiline became a symbol of "evil." Politicians quickly tried to distance themselves from his failed rebellion. Others tried to make their rivals look bad by linking them to Catiline's conspiracy. Cicero, who took credit for saving the state, later praised Catiline's personal qualities in a speech. Cicero said Catiline was a good leader, an effective general, friendly, and strong. This explained why so many men were willing to be friends with him.

The writer Livy used the Catilinarian conspiracy as a model for parts of early Roman history. For example, a story about a man named Marcus Manlius, who rebelled with the support of poor people, is similar to Catiline's story. Virgil, in his epic poem Aeneid, shows Catiline being punished in the underworld.

Even into the time of the Roman emperors, Catiline's name was used to insult unpopular rulers. However, in some rural parts of northern Italy, he was seen as a hero who stood up for the poor. In Tuscany, there was a medieval story that Catiline survived the battle and lived as a local hero. Another story said he had a son who started a powerful family in Florence.

While history has often seen Catiline through the eyes of his enemies, especially Cicero, some modern historians have looked at him differently. Some argue that Catiline was not as evil as he was portrayed. They suggest that the conspiracy might have been exaggerated by Cicero for his own political gain. Others argue that Catiline rebelled to fight against corruption in the senate. However, most of the writings that survive are from Cicero and are against Catiline. So, it is hard to know the full truth.

Cultural Depictions

- Antonio Salieri wrote an opera called Catilina in 1792. It was about the Catilinarian conspiracy. The opera was not performed until 1994 because of its political meaning during the French Revolution.

- Steven Saylor's 1993 novel Catilina's Riddle is about the events between Catiline and Cicero in 63 BC. Catiline also appears in Saylor's short story "The House of the Vestals."

- Catiline's conspiracy and Cicero's actions are important parts of the novel Caesar's Women by Colleen McCullough. This book is part of her Masters of Rome series.

- SPQR II: The Catiline Conspiracy' by John Maddox Roberts also discusses Catiline's conspiracy.

- Robert Harris' 2006 book Imperium is based on Cicero's letters. It covers Cicero's career and his growing interactions with Catiline. The next book, Lustrum, is about the five years around the Catilinarian conspiracy.

- The Roman Traitor or the Days of Cicero, Cato and Catiline: A True Tale of the Republic by Henry William Herbert was published in 1853.

- A Pillar of Iron by Taylor Caldwell, published in 1965, tells the story of Cicero's life, especially how it relates to Catiline and his conspiracy.

- A Slave Of Catiline is a book by Paul Anderson. It tells the story of a slave who first helps and then stops Catiline's conspiracy.

- A novel about the conspiracy, The Fall of the Republic, by Scott Savitz, was published in September 2020.

- Bertolt Brecht's unfinished novel The Business Affairs of Mr Julius Caesar gives a fictional account of the Catilinarian conspiracy. In it, Caesar and Crassus are said to be involved for money.

See also

In Spanish: Catilina para niños

In Spanish: Catilina para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |