Catilinarian conspiracy facts for kids

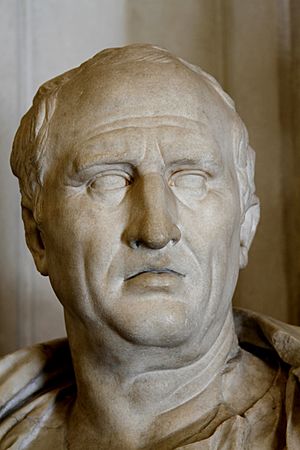

The Catilinarian conspiracy was a plan by Lucius Sergius Catilina (Catiline) to take over the Roman government by force. This happened in 63 BC. Catiline wanted to remove the two top leaders, called consuls, who were Marcus Tullius Cicero and Gaius Antonius Hybrida.

Catiline started this plot after he lost the election to become consul for the year 62 BC. He gathered a group of unhappy people. This group included rich people who had not gotten important jobs, farmers who had lost their land, and soldiers who were in debt. Their plan was to forcefully take control from Cicero and Antonius. In November 63 BC, Cicero found out about the conspiracy. Catiline then ran away from Rome to join his army in Etruria. In December, Cicero found nine more people in Rome who were helping Catiline. The Roman Senate told Cicero to have them executed without a trial. In early January 62 BC, Antonius fought and defeated Catiline in battle, which ended the plot.

It's hard to know the full truth about the conspiracy. The old writings about it were very biased against Catiline. They made him seem worse than he might have been. Most historians today agree that the conspiracy did happen. However, they think that the danger it posed to Rome was made to seem bigger than it was. This helped Cicero look like a hero.

Contents

What Caused the Conspiracy?

Catiline's conspiracy was a big armed uprising against Rome. It was similar to other conflicts like Sulla's civil war and Caesar's civil war. The main stories about it come from Sallust and Cicero. Both of these writers did not like Catiline. Catiline came from a noble family, but his family had not had a consul in a very long time.

He had faced legal problems in 65 and 64 BC but was found innocent. This was because important former consuls spoke up for him. Some old stories say Catiline was part of a "first" conspiracy in 65 BC. But most modern experts believe this earlier plot never actually happened.

Why Catiline Plotted

Catiline had tried to become consul three times by 63 BC, but he lost every time. After his last defeat, he started planning to take the consulship by force.

He brought together several senators who had a bad reputation. These included Publius Cornelius Lentulus Sura, a former consul who had been removed from the Senate for bad conduct. Others were Gaius Cornelius Cethegus, who had little hope for a good future, and Publius Autronius Paetus. Paetus had won an election but then lost his victory and Senate seat due to bribery. Other senators who had been removed for bad conduct also joined. Many others who expected to get important jobs but didn't, also joined. This included Lucius Cassius Longinus and Lucius Calpurnius Bestia.

People who were not senators also joined. Some were frustrated because they couldn't win local elections. Some were in debt. Others hoped to gain money and power from the chaos. Many were from old noble families that were losing their influence, like Catiline's family. What made them a real threat was that they got support from people who had lost their homes after Sulla's civil war. This included soldiers who had fought for Sulla and were promised land or money but didn't get it. They were now in debt because of bad harvests.

Old writings often say that these people joined because they had huge debts that Catiline promised to erase. But historians today say this wasn't the only reason. The shame of not achieving their political goals was also very important.

The conspiracy was only for Roman citizens. It did not involve slaves. Even though Cicero and others worried about another slave rebellion, there is little proof that slaves were part of Catiline's plan. Catiline wanted to take control of the government for himself and his friends, not to start a social revolution.

The failure of a land reform bill earlier in 63 BC also made many poor citizens angry. This bill would have helped poor people get land. There was also a general money crisis that had been going on for a long time. Lenders were asking for their money back and raising interest rates. This pushed many people into debt and financial ruin.

How the Plot Was Discovered

In the autumn of 63 BC, the consul Cicero heard rumors about a plot from a woman named Fulvia. The first real proof came from Marcus Licinius Crassus. Around October 18 or 19, Crassus gave Cicero letters that described plans to kill important citizens. Other reports of armed men gathering also supported Crassus's letters. Because of this, the Senate declared a state of emergency. After hearing about armed men gathering in Etruria, the Senate gave the consuls special powers to deal with the crisis.

By October 27, the Senate learned that Gaius Manlius, a former soldier, had gathered an army near Faesulae. Some historians think Manlius's revolt was separate from Catiline's at first. But others disagree. Cicero sent two governors and two officials to deal with the possible uprising. They were allowed to gather troops and were ordered to set up night watches.

Catiline stayed in Rome. The anonymous letters to Crassus mentioned him, but this wasn't enough proof. However, after messages from Etruria directly linked him to the uprising, he was accused of public violence in early November. The conspirators met, probably on November 6. They found two people willing to try to kill Cicero. Cicero claimed the conspirators also planned to burn Rome. Sallust says this claim made the common people of Rome turn against Catiline. But modern historians don't believe Catiline truly wanted to destroy the city.

After the attempts on Cicero's life failed on November 7, 63 BC, Cicero called the Senate together. He gave his first speech against Catiline, openly accusing him of the conspiracy. Catiline tried to defend himself, but he was shouted down. He quickly left Rome to join Manlius's men in Etruria. He wrote a letter, probably the one saved by Sallust. In it, he asked a friend to protect his wife. He said he was leaving because he had been unfairly denied honors and denied owing any debts.

The Plan Unfolds

When Catiline arrived at Manlius's camp, he started acting like a consul. The Senate immediately declared both Catiline and Manlius "public enemies." Cassius Dio's history says Catiline was quickly found guilty of public violence. The Senate sent Cicero's fellow consul, Gaius Antonius Hybrida, to lead troops against Catiline. Cicero was put in charge of defending Rome.

What Happened to the Conspirators

At this time, Cicero found out about another plot. Publius Cornelius Lentulus Sura, one of the current officials, was trying to get the Allobroges, a tribe from Gaul, to help Catiline. But the Allobroges told Cicero about Lentulus's plans. Cicero used the Allobroges' messengers as secret agents. He asked them to help find as many conspirators in Rome as possible. With their help, on December 2 or 3, five men were arrested: Lentulus, Cethegus, Statilius, Gabinius, and Caeparius. The Gallic messengers told the Senate everything they knew, and the prisoners confessed. Lentulus had to give up his official job, and the others were put under house arrest.

On December 4, someone tried to say Crassus was part of the plot, but no one believed them, and the informer was put in prison. The same day, someone tried to free the prisoners. The Senate decided to have a debate about what to do with them the next day.

The debate about the prisoners happened in the Temple of Concord. Cicero, as consul, had special powers to protect the state. But these powers didn't give him formal protection from legal challenges. Cicero likely wanted the Senate's advice so that the whole Senate would share responsibility for any executions. Later, when he was accused of killing citizens without a trial, he said he was just following the Senate's advice.

The Senate members spoke in order of importance. Former consuls all said the prisoners should be executed. But when Julius Caesar, who was about to become an official, spoke, he suggested life imprisonment or holding them until a trial. Caesar's milder idea convinced many senators. However, his idea was also against the law, as life sentences without trial weren't allowed. Cicero then gave a speech urging quick action. But the senators didn't decide on execution until Cato the Younger spoke.

Cato gave a very strong speech. He spoke against Caesar and suggested Caesar might be secretly helping the conspirators. He also talked about how the state's morals were declining. Cato urged the senators to be strict, like their ancestors. He argued that quick executions would make Catiline's supporters leave him. He also exaggerated that Catiline was about to attack Rome very soon. Cato's speech convinced the Senate.

The Senate agreed with Cicero's idea to execute the conspirators without a trial. Cicero carried out the executions. When it was done, he announced, "They have lived," meaning they were dead. His fellow senators then called him "father of the fatherland."

Catiline's Final Defeat

After the five prisoners were killed, Catiline's army lost a lot of support. Some people in Rome, like the official Metellus Nepos, wanted to give command of the army to Pompey, asking Pompey to save Rome. Early the next year, near Pistoria, Catiline's remaining men, about three thousand, fought against Antonius's forces. Antonius, who was now a governor, claimed he was sick, so Marcus Petreius actually led the army. Catiline's forces were defeated, ending the crisis. Catiline was killed in the battle. Antonius was honored as a victorious general.

What Happened Next

Cicero was at first praised for saving Rome, but he didn't get all the credit, which made him unhappy. Cato was also praised for making the Senate act. Soon after the executions, some people turned against Cicero's actions. At the end of his year as consul, two officials blocked Cicero from giving his farewell speech. One of them, Quintus Caecilius Metellus Nepos, wanted to accuse Cicero of killing citizens without a trial. But the Senate stopped him. They threatened to declare anyone who brought such a charge a public enemy.

In the years that followed, Cicero's enemies grew stronger. Publius Clodius Pulcher, an official in 58 BC, passed a law that banished anyone who had executed a citizen without a trial. Cicero quickly fled Rome to Greece. His exile was later ended, and he was called back to Rome the next year by Pompey. People have different opinions on how well Cicero saved the republic. Cicero said he had saved the state, and many historians agree that his actions were necessary in an emergency. However, some historians point out that he did this by ignoring legal rules and the rights of citizens. This also showed that the consul didn't trust the court system that Sulla had set up.

|

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |