David Walker (abolitionist) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

David Walker

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | September 28, 1796 Wilmington, North Carolina, U.S.

|

| Died | August 6, 1830 (aged 33) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Abolitionist, journalist |

| Known for | An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World (1830) |

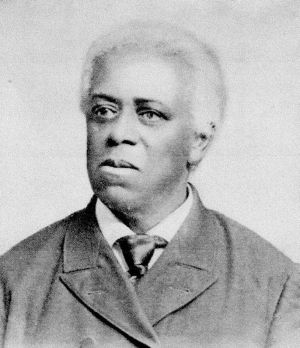

David Walker (born September 28, 1796 – died August 6, 1830) was an important American abolitionist, writer, and activist who fought against slavery. Even though his father was enslaved, David Walker was born free because his mother was free. This was due to a law called partus sequitur ventrem, which meant a child's status followed their mother's.

In 1829, while living in Boston, Massachusetts, Walker published a powerful pamphlet called An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World. This writing called for Black people to unite and fight against the injustice of slavery. The Appeal showed the terrible problems and unfairness of slavery. It also reminded people that they had a duty to act based on their religious and political beliefs. At the time, some people were shocked and worried about what the pamphlet might cause. People in the Southern states were especially upset. Because of Walker's ideas, new laws were made to stop "rebellious writings" from being shared. North Carolina even passed very strict laws to control enslaved people and free Black people.

David Walker's son, Edward G. Walker, later became a lawyer. In 1866, he was one of the first two Black men elected to the Massachusetts State Legislature.

Contents

David Walker's Early Life

David Walker was born in Wilmington, North Carolina. Historians are not completely sure about the exact year he was born. His mother was a free woman, and his father had been enslaved but died before David was born. Because of the law that said a child's status followed the mother's, David Walker was born a free person.

Walker found the unfair treatment of other Black people very hard to bear. He once thought, "If I stay in this bloody land, I will not live long. I cannot stay where I must always hear the chains of enslaved people and face insults from their cruel enslavers." Because of these feelings, he moved to Charleston, South Carolina as a young adult. This city was a place where many free Black people could improve their lives. There, he joined a strong community of African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME Church) activists. This was the first Black church group in the United States. He later visited and likely lived in Philadelphia, which was a center for shipbuilding and had a very active Black community. The AME Church was founded in Philadelphia.

Family Life

By 1825, Walker had settled in Boston. Slavery had already ended in Massachusetts after the American Revolutionary War. On February 23, 1826, he married Eliza Butler. Her family was a well-known Black family in Boston. David and Eliza had two children: Lydia Ann Walker, who died young, and Edward G. Walker (1831–1910).

Working and Activism

David Walker started a used clothing store in the City Market. Later, he owned another clothing store on Brattle Street near the docks.

Walker actively helped runaway enslaved people and supported those who were "poor and needy." He was involved in many community and religious groups in Boston. He joined Prince Hall Freemasonry, an organization started in the 1780s that fought against unfair treatment of Black people. He also helped start the Massachusetts General Colored Association, which was against the idea of sending free Black Americans to live in Africa. Walker was also a member of Rev. Samuel Snowden's Methodist church. He often spoke publicly against slavery and racism.

Walker and Thomas Dalton helped publish a speech by John T. Hilton in 1828. This speech was given at the African Grand Lodge of Boston.

Even though Black families in Boston still faced racism, their lives were generally better in the 1820s. Black people in Boston were very skilled and active in their community. By the end of 1828, David Walker had become a leading voice in Boston against slavery.

Freedom's Journal

David Walker worked as a sales agent in Boston for Freedom's Journal. This newspaper was published in New York City from 1827 to 1829. It was the first newspaper in the United States owned and run by African Americans. Walker also wrote for the newspaper.

Walker's Appeal

How the Appeal Was Published

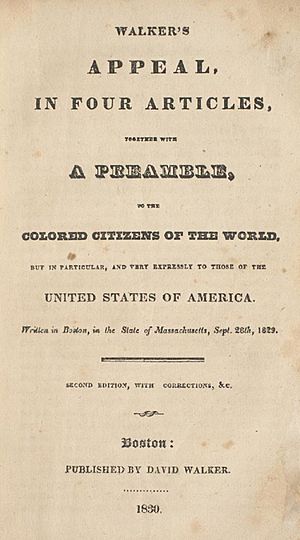

In September 1829, David Walker published his famous pamphlet. Its full title was Walker's Appeal, in Four Articles; Together with a Preamble, to the Colored Citizens of the World, but in Particular, and Very Expressly, to Those of the United States of America, Written in Boston, State of Massachusetts, September 28, 1829. The first edition is very rare. A second and then a third edition were published in 1830. The second edition, from 1830, shared his views even more strongly.

Walker urged his readers to actively fight against their oppression, even if it was risky. He also wanted white Americans to understand that slavery was morally wrong and against religious principles. The Appeal was almost forgotten by 1848. However, many other abolitionist writings, inspired by Walker, had appeared by then. The Appeal gained new life when it was reprinted in 1848 by a Black minister named Henry Highland Garnet. Garnet included the first biography of David Walker in his reprint. He also added his own speech, "Address to the Slaves of the United States of America." This speech was considered so radical that it was not published when he first gave it in 1843. The famous white abolitionist, John Brown, helped get Garnet's book printed.

Main Ideas in the Appeal

Challenging Racism

Walker strongly spoke out against the racism common in the early 1800s. He especially criticized groups like the American Colonization Society. This group wanted to send all free Black people from the United States to a colony in Africa, which is how Liberia was started. Walker also wrote against the ideas of former President Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson had written that Black people were not as smart or capable as white people. Walker explained, "I say, that unless we prove Mr. Jefferson's arguments about us are wrong, we will only make them seem true."

He rejected the idea in the United States that dark skin meant someone was less human. He challenged critics to find any historical record that said the Egyptians treated the children of Israel as if they were not human, referring to the time they were enslaved in Egypt.

Fighting for Equal Rights

By the 1820s and 1830s, some people and groups were starting to support equal rights for Black men and women. However, there was no national anti-slavery movement when Walker's Appeal was published. As historian Herbert Aptheker wrote, fighting against slavery was not for the weak. Slaveholders in the first half of the 1800s were a very powerful economic group in the nation. Their enslaved people and land were worth billions of dollars. This economic power also gave them great political power.

Aptheker was talking about a part of the Constitution called the Three-Fifths Compromise. This rule counted three-fifths of the enslaved population towards a state's total population. This helped decide how many representatives a state would have in Congress and how many votes it got in the electoral college. This gave white voters in the South much more power than their numbers showed, because neither enslaved people nor free Black people could vote. This led to Southern politicians having huge power and many Southerners being elected as president.

The Harmful Effects of Slavery

The Appeal described the terrible effects of slavery and the unfair treatment of free Black people. People who were not enslaved were still controlled by special rules. This was because society believed they could not control themselves and might go beyond the limits placed on them.

A Call to Action

Resisting Oppression

In his Appeal, Walker urged the Black community to take action against slavery and discrimination. Historian Paul Goodman said that what made Walker's writing powerful was his argument for racial equality. He also believed that Black people must actively work to achieve it. Scholar Chris Apap agreed, saying that the Appeal rejected the idea that Black people should only pray for their freedom.

Apap highlighted a part of the Appeal where Walker tells Black people to "Never try to gain freedom or natural right from our cruel oppressors and murderers, until you see your way clear. When that hour arrives and you move, do not be afraid or discouraged." Apap explained that "do not be afraid or discouraged" is a quote from the Bible (2 Chronicles 20:15). In the Bible, the Israelites are told not to be afraid because God would fight for them without them having to do anything. But Walker said the Black community must "move." Apap believes that by telling his readers to "move," Walker meant that Black people should not just wait for God to fight their battles. They must take action to claim what is rightfully theirs.

Walker wrote: "We colored people of these United States are the most degraded, wretched, and miserable set of beings that ever lived since the world began. I pray God, that none like us ever may live until time shall be no more. They tell us of the Israelites in Egypt, the Helots in Sparta, and of the Roman slaves... whose sufferings under those ancient and heathen nations, were, in comparison with ours, under this enlightened and Christian nation, no more than a zero. Or in other words, those heathen nations of antiquity had but little more among them than the name and form of slavery; while misery and endless suffering were saved, it seems, in a phial, to be poured out upon our fathers, ourselves, and our children by Christian Americans."

Walker's Appeal argued that Black people had to take responsibility for themselves if they wanted to overcome oppression. According to historian Peter Hinks, Walker believed that the key to improving the race was a strong commitment to personal moral improvement. This included education, temperance (avoiding alcohol), Protestant religious practice, regular work habits, and self-control.

Walker argued, "America is more our country than it is the whites' — we have made it rich with our blood and tears."

Importance of Education and Religion

Education and religion were very important to Walker. He believed that Black people gaining knowledge would not only prove that they were not naturally inferior, but it would also scare white people. He wrote, "The very idea of educating colored people scares our cruel oppressors almost to death." Walker believed that those who were educated had a special duty to teach others. He urged literate Black people to read his pamphlet to those who could not read. He explained, "It is expected that all colored men, women and children, of every nation, language and tongue under heaven, will try to get a copy of this Appeal and read it, or get someone to read it to them, for it is written especially for them."

Regarding religion, Walker strongly criticized the hypocrisy of "pretended preachers of the gospel of my Master." These preachers, he said, not only owned enslaved people but treated them as harshly as any non-believer. He felt they were only interested in taking the blood and groans of enslaved people to praise the Lord Jesus Christ. He argued that Black people must reject the idea that the Bible supported slavery. He also urged white people to apologize to God before God punished them for their wickedness. Historian Sean Wilentz said that Walker, in his Appeal, "offered a version of Christianity that was free of racist errors, one which held that God was fair to all His creatures."

David Walker wrote: "There is great work for you to do... You have to prove to the Americans and the world that we are men, and not animals, as we have been described and treated by millions. Remember, let the goal of your work among your brothers and sisters, especially the young people, be to spread education and religion."

To White Americans

A Chance for Change

Even with his strong criticism of the United States, Walker's Appeal did not say the nation was beyond saving. He accused white Americans of the sin of making "colored people of these United States" into "the most degraded, wretched, and miserable set of beings that ever lived since the world began." But historian Sean Wilentz argued that "even in his most bitter parts, Walker did not reject... republican principles, or his native country." Walker suggested that white Americans only needed to think about their own stated values to see how wrong their ways were.

Unnecessary Praise for Kindness

Walker believed that white people did not deserve praise for freeing some enslaved people. Historian Peter Hinks explained that Walker argued, "Whites gave nothing to blacks upon manumission (freedom) except the right to use the liberty they had wrongly stopped them from using in the past. They were not giving blacks a gift but rather returning what they had stolen from them and God. To praise whites as the source of freedom was therefore to insult God by denying that he was the source of all good things and the only one to whom one owed thanks."

Black Nationalism

Walker is often seen as an abolitionist with Black nationalist ideas. This is largely because he imagined a future where Black Americans would govern themselves. He wrote in the Appeal: "Our sufferings will end, no matter what Americans do. Then we will need all the learning and talents, and perhaps more, to govern ourselves."

Scholars like historian Sterling Stuckey have noted the connection between Walker's Appeal and Black nationalism. In his 1972 book, The Ideological Origins of Black Nationalism, Stuckey suggested that Walker's Appeal "would become a foundation of ideas... for Black Nationalist theory." While some historians have said Stuckey might have overemphasized Walker's role in creating a Black nation, Thabiti Asukile defended Stuckey's view in a 1999 article. Asukile wrote that it would be hard to prove that later supporters of Black nationalism, who wanted a separate nation based on land, could not trace some of their ideas back to Walker's writings.

David Walker wrote: "This country is as much ours as it is the whites', whether they will admit it now or not, they will see and believe it by and by."

Walker shared his pamphlet through networks of Black communication along the Atlantic coast. These networks included free and enslaved Black civil rights activists, workers, Black church groups, and contacts with free Black aid societies.

How People Reacted

Stopping the Appeal

Officials in the Southern states tried to stop the Appeal from reaching their residents. Black people in Charleston and New Orleans were arrested for sharing the pamphlet. Authorities in Savannah, Georgia, even banned Black sailors from getting off ships (Negro Seamen Act). This was because Southern governments, especially in port cities, worried about information reaching Black people, both free and enslaved. Many Southern government groups called the Appeal rebellious and gave harsh punishments to those who shared it. Despite these efforts, Walker's pamphlet was widely shared by early 1830. When they failed to stop the Appeal, Southern officials criticized both the pamphlet and its author. Newspapers like the Richmond Enquirer attacked what it called Walker's "monstrous slander" of the region. The anger over the Appeal even led Georgia to offer a reward of $10,000 for anyone who could bring Walker in alive, and $1,000 if he was dead.

Immediate Impact

Walker's Appeal was not popular with most abolitionists or free Black people at first because its message was seen as too extreme.

However, a few white anti-slavery supporters became more radical because of the pamphlet. The Boston Evening Transcript noted in 1830 that some Black people saw the Appeal "as if it were a star in the east guiding them to freedom and emancipation." White Southerners' fears about a Black-led challenge to slavery—fears the Appeal made worse—came true just a year later with Nat Turner's Rebellion. This rebellion made them pass even harsher laws to control enslaved people and free Black people.

William Lloyd Garrison, a very important American abolitionist, started publishing The Liberator in January 1831, soon after the Appeal was published. Garrison believed slaveowners would be punished by God. He did not agree with the violence Walker suggested, but he knew that slaveowners were risking disaster by refusing to free their enslaved people. Garrison wrote, "Every sentence that they write — every word that they speak — every resistance that they make, against foreign oppression, is a call upon their slaves to destroy them."

Walker's Appeal and the slave rebellion led by Nat Turner in Virginia in 1831 scared slaveowners. There is no proof that the Appeal directly caused or inspired Turner, but it could have, since the two events happened only a few years apart. White people were very worried about future rebellions. Southern states passed laws that restricted free Black people and enslaved people. Many white people in Virginia and North Carolina believed that Turner was inspired by Walker's Appeal or other abolitionist writings.

Lasting Influence

Walker influenced important figures like Frederick Douglass, Nat Turner, William Lloyd Garrison, Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm X. You can hear echoes of his Appeal in Douglass's 1852 speech, "The Meaning of the Fourth of July for the Negro":

"For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake. The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced."

Historian Herbert Aptheker said that Walker's Appeal is the first strong written attack on slavery and racism from a Black man in the United States. This was why it was so powerful in its own time. This is also why it remains so important and impactful even today. He said that never before or since has there been such a passionate criticism of the nation's hypocrisy—how it claimed to be democratic, friendly, and equal. And Walker did this not as someone who hated the country, but as someone who hated the systems that damaged it and made it a disgrace to the world.

Death

David Walker died in the summer of 1830, just five years after he moved to Boston. Although some rumors suggested he was poisoned, most historians believe he died naturally from tuberculosis. This disease was common at the time, and Walker's only daughter, Lydia Ann, had died from it the week before he did. Walker was buried in a South Boston cemetery for Black people. His likely grave site is still unmarked.

After Walker died, his wife could not keep up the yearly payments for their house. She lost their home, which Walker had, in a way, predicted in his Appeal: "But I must, really, observe that in this very city, when a man of color dies, if he owned any real estate it most generally falls into the hands of some white persons. The wife and children of the deceased may weep and lament if they please, but the estate will be kept safe enough by its white owner."

His son, Edward G. Walker (also known as Edwin G. Walker), was born after David Walker's death. In 1866, Edward became the first Black man elected to the Massachusetts State Legislature.

Legacy

Many historians consider David Walker a very important abolitionist and an inspiring figure in American history.

- The Library of Congress had an exhibit called Free Blacks in the Antebellum Period. It highlighted Walker's importance, along with other key Black abolitionists. It noted that "Free people of color like Richard Allen, Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, David Walker, and Prince Hall became nationally known by writing, speaking, organizing, and fighting for their enslaved fellow citizens."

- The National Park Service offers walking tours for the Boston African American National Historic Site. These tours include the Black Beacon Hill community. The tours talk about David Walker, who was a key part of the Black neighborhood and city activists. An online version of the tour is also available.

See also

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |