Partus sequitur ventrem facts for kids

Partus sequitur ventrem is a Latin phrase meaning "that which is born follows the womb." It was a very important law made in colonial Virginia in 1662. This law said that children would have the same legal status as their mother. So, if a mother was enslaved, her children would also be born into slavery. This rule came from old Roman laws, especially those about slavery and property.

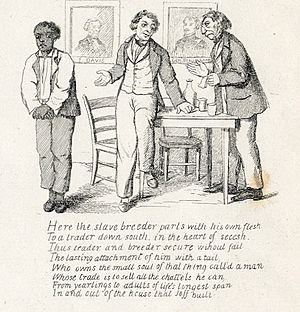

The biggest effect of partus sequitur ventrem was that all children born to enslaved women became slaves themselves. This law quickly spread from Virginia to all Thirteen Colonies. It meant that the biological father of a child born to an enslaved woman had no legal connection to the child. All rights to the children belonged to the slave owner. This allowed slave owners to profit from the work of children born into slavery. The law also meant that mixed-race children with white mothers were born free. Early groups of Free Negros in the American South often came from relationships between free working-class women and black men.

Similar laws, also based on civil law, were used in other European colonies in the Americas and Africa. These colonies were set up by the British, Spanish, Portuguese, French, or Dutch.

Contents

History of the Law

How the Law Started

In 1619, a group of "twenty and odd" African people arrived in the Colony of Virginia. This marked the start of bringing Africans to England's colonies in North America. They had been taken from a Portuguese slave ship. The Portuguese had started the Atlantic slave trade a century earlier.

During the colonial era, English leaders struggled to decide the legal status of children born in the colonies. This was especially true for children born to an English person and a "foreigner," or to two foreigners.

English common law usually said that a child's legal status came from their father. This was known as pater familias, meaning "father of the family." Common law required fathers to care for all their children, including those born outside of marriage. They had to provide food and shelter. Fathers also had the right to make their children work or hire them out. This helped children learn skills and become independent adults. Child labor was important for families in England and for the colonies to grow. Children were seen as property of the father, but they would grow out of this status as they got older.

Regarding personal property (like animals or movable goods), common law said that any profits or offspring from this property belonged to the owner. But in 1662, the colonial government in Virginia changed this for enslaved people. They added the partus sequitur ventrem rule to their slavery laws. This rule said that children born in the colonies would take the status of their mothers. So, children of enslaved mothers were born into slavery as property, no matter who their fathers were. While partus sequitur ventrem existed in English common law for livestock, it did not make English people into property.

Elizabeth Key's Fight for Freedom

In 1656, a mixed-race woman named Elizabeth Key Grinstead was illegally considered enslaved. She fought for her freedom in court in colonial Virginia and won. Key's case was special because her English father was a member of the House of Burgesses, a colonial government group. He had recognized Elizabeth as his daughter. She was also baptized as a Christian. Before he died, he arranged for her to be an indentured servant until she was an adult. This meant she would work for someone for a set time, then be free.

However, the man she was indentured to sold her contract to another man. This second man kept her enslaved longer than her contract allowed. When this second owner died, his estate (his property) listed Elizabeth Key and her mixed-race son as "Negro slaves." Elizabeth, with her son's father, William Grinstead, acting as her lawyer, sued the estate. She argued that she was an indentured servant who had served her time and that her son should be free. The Virginia General Court first agreed with her, but then changed its mind after the estate appealed. Elizabeth then took her case to the Virginia General Assembly, which finally agreed with her arguments.

Historian Taunya Lovell Banks explains that children born to English parents outside England were English subjects. Others could become "naturalized subjects," though there wasn't a clear process for this in the colonies. The status of children with only one English parent was unclear, as non-whites were not considered subjects. Because non-whites were later denied civil rights, mixed-race people seeking freedom often had to emphasize their English (or later, European) family background.

Because of freedom lawsuits like Elizabeth Key's, the Virginian House of Burgesses passed the partus sequitur ventrem law. They noted that "doubts have arisen whether children got by an Englishmen upon a negro woman should be slave or free."

After the American Revolution, slavery laws in the United States kept these rules. Virginia made a law in 1785 saying that only those who were slaves at that time, "and the descendants of the females of them," could be slaves. Kentucky adopted this law in 1798. Mississippi passed a similar law in 1822, and Florida in 1828. Louisiana, which used civil law from its French past, added similar wording in 1825. Other states adopted this rule through court decisions. In short, the partus sequitur ventrem law helped ensure a steady supply of enslaved people for economic reasons.

Mixed-Race Enslaved People

By the 1700s, the enslaved population in the colonies included mixed-race children. These children had white ancestors and were sometimes called mulattoes (half Black), quadroons (one-quarter Black), or octoroons (one-eighth Black). Their fathers were often white plantation owners, overseers, or other powerful men. Their mothers were enslaved women, who were sometimes also of mixed race.

Many mixed-race enslaved people lived in families at Thomas Jefferson's Monticello plantation. In 1773, his wife, Martha Wayles, inherited over one hundred enslaved people from her father, John Wayles. Among them were six mixed-race children (three-quarters white) whom her father had with an enslaved woman named Betty Hemings. Martha Wayles's mixed-race half-sisters and half-brothers included the much younger Sally Hemings. Later, after his wife died, Jefferson had six children with Sally Hemings. Four of these children lived to adulthood. Since their mother was enslaved, they were also born into slavery.

Under Virginia law at the time, if the Jefferson–Hemings children had been free, being seven-eighths European ("octoroon") would have made them legally white. Jefferson allowed the two oldest children to "escape." He freed the two youngest in his will. As adults, three of the Jefferson–Hemings children lived as white people. Beverly and Harriet Hemings lived in the Washington, D.C. area. Eston Hemings Jefferson lived in Wisconsin. Eston had married a mixed-race woman in Virginia. Both of their sons served as soldiers for the Union during the Civil War. The oldest son became a colonel.

For a long time, historians doubted stories that Jefferson had children with Sally Hemings. But in 1998, a Y-DNA test confirmed that a male descendant of Sally Hemings (through Eston Hemings's family) was directly related to the male line of the Jefferson family. Thomas Jefferson was known to be at Monticello each time Hemings became pregnant. Most historical evidence supports that he was the father.

Mixed-Race Communities in the South

In colonial cities along the Gulf of Mexico, like New Orleans, Savannah, and Charleston, a social group called Creole peoples developed. These were educated free people of color. They were often descendants of white fathers and enslaved black or mixed-race women. As a group, they often married each other, got formal education, and owned property, including enslaved people.

Also, in the Upper South, some slave owners freed their enslaved people after the American Revolution. This was done through a process called manumission. The number of free black men and women grew from less than 1% in 1780 to more than 10% in 1810. At that time, 7.2% of Virginia's population was free black people, and 75% of Delaware's black population was free.

Regarding the unfairness of white men having children with enslaved women, diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut wrote: "This only I see: like the patriarchs of old our men live all in one house with their wives and their concubines, the Mulattoes one sees in every family exactly resemble the white children — every lady tells you who is the father of all the Mulatto children in every body's household, but those [Mulatto children] in her own [household], she seems to think drop from the clouds or pretends so to think..."

Similarly, in her book Journal of a Residence on a Georgia Plantation in 1838–1839 (1863), Fanny Kemble, an English woman married to an American plantation owner, pointed out how wrong it was for white slave owners to keep their mixed-race children enslaved.

However, some white fathers formed common-law marriages with enslaved women. They sometimes freed the woman and children. They might also transfer property to them, arrange for them to learn a trade, get an education, or move to the North. Some white fathers paid for their mixed-race children to attend colleges that accepted all races, like Oberlin College. In 1860 Ohio, at Wilberforce University (started in 1855), which was owned and run by the African Methodist Episcopal church, most of the two hundred students were mixed-race. Their tuition was paid by their white fathers.

See also

In Spanish: Partus sequitur ventrem para niños

In Spanish: Partus sequitur ventrem para niños

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |