James McCune Smith facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

James McCune Smith

|

|

|---|---|

Inscription: "First regularly-educated Colored Physician in the United States"

|

|

| Born | April 18, 1813 |

| Died | November 17, 1865 (aged 52) Long Island, New York, U.S.

|

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | African Free School Glasgow University(M.D.) |

| Spouse(s) | Malvina Barnet |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Internal medicine |

| Institutions | Colored Orphan Asylum Wilberforce College |

James McCune Smith (born April 18, 1813 – died November 17, 1865) was an important American doctor, pharmacist, and writer. He was also a strong leader in the abolitionist movement, which worked to end slavery. Born in Manhattan, he made history as the first African American to earn a medical degree from the University of Glasgow in Scotland. When he returned to the United States, he became the first African American to open and run a pharmacy in the country.

For nearly 20 years, Dr. Smith worked as a physician at the Colored Orphan Asylum in Manhattan. He was also a public thinker who wrote many articles for medical journals and joined important scientific groups. He used his knowledge of medicine and statistics to prove wrong the common, unfair ideas about race, intelligence, and society. Even though he was a brilliant doctor, he was never allowed to join the American Medical Association or local medical groups. This was likely due to the racism he faced throughout his career.

Smith was especially known for his work as an abolitionist. He was a member of the American Anti-Slavery Society. With Frederick Douglass, a famous abolitionist, he helped create the National Council of Colored People in 1853. This was the first lasting national organization for Black people. Douglass even called Smith "the single most important influence on his life."

Dr. Smith was part of the Committee of Thirteen, a group formed in Manhattan in 1850. They worked to fight the new Fugitive Slave Law. This law made it harder for enslaved people to escape to freedom. Smith and his group helped runaway slaves through the Underground Railroad. Many other leading abolitionists were his friends and co-workers. From the 1840s, Smith gave talks and wrote articles to challenge racist beliefs about the abilities of Black people.

Both James McCune Smith and his wife, Malvina Barnet, were of mixed African and European heritage. As Dr. Smith became successful, he built a home in a neighborhood that was mostly white. In the 1860 census, he and his family were listed as white, just like their neighbors. (Ten years earlier, in 1850, when they lived in a mostly African-American neighborhood, they had been listed as having mixed ancestry.)

Dr. Smith worked as the physician at the Colored Orphan Asylum for almost 20 years. In July 1863, during the draft riots in Manhattan, a mob burned down the asylum. For their safety, Smith moved his family and his medical practice to Brooklyn. Many other Black families also moved from Manhattan to Brooklyn at that time. The Smiths believed strongly in education for their children. In the 1870 census, his wife and children were still listed as white.

To avoid racial discrimination and find more opportunities, his children lived as part of white society. His four sons who survived to adulthood married white women. His unmarried daughter lived with one of her brothers. They became teachers, a lawyer, and business people. In the 20th century, historians rediscovered Dr. Smith's amazing achievements as a pioneering African-American doctor. His descendants, who identified as white and didn't know about him, learned about him in the 21st century. This happened when a great-great-great-granddaughter took a history class and found his name in her grandmother's family bible. In 2010, some of Smith's descendants ordered a new tombstone for his grave in Brooklyn. They gathered to honor him and their African-American heritage.

Contents

Early Life and Education

James McCune Smith was born into slavery in Manhattan in 1813. He gained his freedom on July 4, 1827, when he was 14 years old. This was the day the Emancipation Act of New York officially freed the remaining enslaved people in New York. His mother, Lavinia, was also an enslaved woman who later became free. Smith described her as a "self-emancipated woman" in 1855. She was born into slavery in South Carolina and brought to New York as a slave. His father was Samuel Smith, a white merchant who had brought Lavinia to New York. James grew up only with his mother. As an adult, he mentioned having other white relatives through his mother's family, some of whom owned slaves and others who were enslaved.

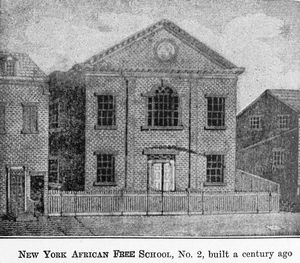

Smith went to the African Free School (AFS) #2 in Manhattan. He was known as a "very bright student." In 1824, when he was 11, he was chosen to give a speech to the Marquis de Lafayette, a French war hero visiting the school. Many boys from the AFS, including Smith, went on to have successful careers. Some even worked with him in the fight against slavery.

During his studies, Smith was taught by Reverend Peter Williams Jr. Williams was also a graduate of the African Free School and became one of the first African-American priests in the Episcopal Church. After graduating, Smith tried to get into Columbia University and Geneva Medical College in New York. However, he was turned away because of racial discrimination. Reverend Williams and other abolitionists helped Smith get money for his trip and education in Scotland. Smith wrote in his journal during his sea voyage that he felt a strong sense of purpose. When he arrived in Liverpool, he thought, "I am free!"

Through his connections with abolitionists, he was welcomed by anti-slavery groups in London. Historian Thomas M. Morgan noted that Smith enjoyed the greater racial tolerance in Scotland and England. These countries had ended slavery in the 1770s, much earlier than New York (which ended it in 1827). Smith studied at the University of Glasgow. He earned a bachelor's degree in 1835, a master's degree in 1836, and a medical degree in 1837. He also completed an internship in Paris.

Smith knew he would face discrimination when he returned to the United States. When he tried to book a trip back home, the ship captain refused to let him on board because of his race. When Smith finally returned to Manhattan, his former classmates and teachers gave him a hero's welcome. They praised his strong desire to fight for civil rights in America.

Family Life

After settling back in New York City, James McCune Smith married Malvina Barnet in the early 1840s. Malvina was a free woman of color who had graduated from the Rutgers Female Institute. They had eleven children, but only five lived to adulthood.

In 1850, the Smith household included his mother, Lavinia, and other relatives or friends. At that time, James and Malvina had three children. Everyone in their home was listed as having mixed ancestry. They lived in a diverse neighborhood where many neighbors were white immigrants from Europe.

By 1860, Dr. Smith was very successful. He had moved to a new street and had a large house built. His property was worth a lot of money. His household included a live-in servant. In the census that year, no one in his household was given a racial label, which meant they were considered white by the census taker.

After the draft riots in Manhattan in 1863, Dr. Smith and his family, like many other prominent Black families, moved from Manhattan to Brooklyn. They no longer felt safe in their old neighborhood.

In the 1870 census, Malvina, now a widow, and their four children were living in Brooklyn. All of them were listed as white. Their son James W. Smith, who had married a white woman, was living separately and working as a teacher; he was also listed as white. The Smith children still at home were Maud, Donald, John, and Guy, and all were attending school. These five children survived to adulthood: James, Maud, Donald, John, and Guy. The sons married white women, but Maud never married. All of them were listed as white from 1860 onward.

They became teachers, a lawyer, and business people. Dr. Smith's amazing achievements as a pioneering African-American doctor were rediscovered by historians in the 1900s. His descendants, who identified as white and didn't know about him for generations, learned about him in the 2000s. This happened when a great-great-great-granddaughter took a history class and found his name in her grandmother's family Bible. In 2010, several of Smith's descendants ordered a new tombstone for his grave in Brooklyn. They gathered to honor him and their African-American heritage.

Career Highlights

Medicine

Dr. James McCune Smith received his medical degree from Glasgow University in 1837. Its medical school was one of the best in Europe. After graduating, he received a special residency in women's health at Glasgow's Lock Hospital. Based on his work there, he published two articles in the London Medical Gazette. These were the first scientific articles known to be published by an African American in a scientific journal. In these articles, he exposed how an experimental drug was used on female patients without their permission, which was wrong.

When Smith returned to Manhattan in 1837, the Black community welcomed him as a hero. He said at a gathering, "I have worked hard to get an education, no matter the cost, and to use that education for the good of our country." He was the first university-trained African-American doctor in the United States. During his 25 years of practice, he was also the first Black person to have articles published in American medical journals. However, he was never allowed to join the American Medical Association or local medical groups.

He opened his own practice in Lower Manhattan, performing surgery and treating both Black and white patients. He also started an evening school to teach children. He opened what is believed to be the first Black-owned and operated pharmacy in the United States, located at 93 West Broadway. His friends and fellow activists often met in the back room of his pharmacy to discuss their work to end slavery.

In 1846, Smith became the only doctor for the Colored Orphan Asylum. This asylum, also known as the Free Negro Orphan Asylum, was located at Forty-fourth Street and Fifth Avenue. Before Smith, the asylum relied on doctors who volunteered their time. He worked there for nearly 20 years. The asylum was founded in 1836 by Quaker philanthropists in New York. To protect the children, Smith regularly gave them smallpox vaccinations. The main causes of death at the asylum were infectious diseases like measles, smallpox, and tuberculosis. Besides caring for orphans, the home sometimes temporarily housed children whose parents couldn't support them, as jobs were hard to find for free Black people in New York. Many new immigrants from Ireland and Germany in the 1840s and 1850s also competed for jobs.

Dr. Smith was always dedicated to the asylum. In July 1852, he presented the trustees with 5,000 acres of land. This land was given by his friend Gerrit Smith, a wealthy white abolitionist. The land was to be held in trust and later sold to benefit the orphans.

Fighting for Freedom

While in Scotland, Smith joined the Glasgow Emancipation Society and met people involved in the Scottish and English anti-slavery movements. Great Britain had abolished slavery in its empire in 1833. When Smith returned to New York, he quickly joined the American Anti-Slavery Society and worked to end slavery in the United States. He worked well with both Black and white abolitionists. For example, he had a long friendship and wrote letters to Gerrit Smith from 1846 to 1865.

His published speeches quickly brought him to the attention of the national anti-slavery movement. His writings, such as "Destiny of the People of Color" and "Freedom and Slavery for Africans," showed him as a new strong voice. He also led the Colored People's Educational Movement. In 1850, as a member of the Committee of Thirteen, Smith was a key organizer in Manhattan against the new Fugitive Slave Act. This law forced states to help catch escaped slaves. Like similar groups in Boston, his committee helped runaway slaves avoid capture and connected them to the Underground Railroad and other escape routes.

In the mid-1850s, Smith worked with Frederick Douglass to create the National Council of Colored People. This was one of the first lasting national Black organizations. It started with a three-day meeting in Rochester, New York. At this meeting, he and Douglass stressed how important education was for Black people. They urged the creation of more schools for Black youth. Smith wanted choices for both job-training and traditional academic education. Douglass valued Smith's logical approach and said Smith was "the single most important influence on his life." Smith helped calm the more extreme people in the abolitionist movement and insisted on using facts and analysis in arguments. He wrote a regular column in Douglass's newspaper, using the pen name "Communipaw."

Smith was against the idea of free Black Americans moving to other countries. He believed that people born in America had the right to live in the United States. He felt they had earned their place through their hard work and birth. He gathered supporters to go to Albany to speak to the state government. They spoke against plans to support the American Colonization Society, which wanted to send free Black people to the colony of Liberia in Africa. In 1861, he gave money to help restart the Weekly Anglo-African newspaper, which was against emigration.

In the mid-1850s, Smith joined James W.C. Pennington and other Black leaders to create the Legal Rights Association (LRA) in Manhattan. This was a pioneering group that fought for minority rights. The LRA campaigned for nearly ten years against segregated public transportation in New York City. This organization successfully ended segregation in New York. It also served as a model for later rights organizations, including the National Equal Rights League and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which was founded in the early 1900s.

Draft Riots

In July 1863, during the draft riots in Manhattan, Irish rioters attacked Black people throughout the city. They also burned down the orphan asylum where Dr. Smith worked. The staff and Union troops in the city saved the children. Over its almost 30 years, the orphan asylum had taken in 1310 children, usually having about 200 living there at a time.

After the riots, Smith moved his family and business from Manhattan to Brooklyn. Other prominent Black families also made this move. Many buildings in their old neighborhoods were destroyed, and it's estimated that about 100 Black people were killed in the riots. The Smiths no longer felt safe in their old neighborhood and moved to Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

Professional Work and Writings

James McCune Smith was a very active writer and essayist. John Stauffer, a historian from Harvard University, said, "He was one of the leaders in the movement to end slavery, and he was one of the most original and creative writers of his time."

In 1839, he took over from Samuel Cornish as editor of The Colored American, a weekly newspaper in New York. Among his notable writings was a debate with John Hughes, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of New York, who was known for his racist and anti-abolitionist views.

In 1840, Smith wrote the earliest known medical case report by a Black doctor. It was called "Case of Ptyalism with fatal termination." In 1844, Smith published an article in the New York Journal of Medicine. This was the earliest known medical article by a Black doctor in an American journal.

He used his medical training to challenge popular false ideas about differences between races. In 1843, he gave a series of lectures called Comparative Anatomy and Physiology of the Races. He used these lectures to show the flaws of phrenology. This was a so-called 'scientific' practice of the time that was used to make racist conclusions and link negative traits to people of African descent. He also rejected homeopathy, which was an alternative to the scientific medicine taught in universities. Even though he had a successful medical career, Smith was never allowed to join the American Medical Association or local medical groups because of racial discrimination.

In Glasgow, he learned about the new science of statistics. He published many articles using his statistical training. For example, he used statistics to prove wrong the arguments of slave owners. They claimed that Black people were less capable and that enslaved people were better off than free Black people or white city workers. To do this, he created statistical tables using census data.

When John C. Calhoun, who was then the U.S. Secretary of State, claimed that freedom harmed Black Americans and that the 1840 U.S. Census showed high rates of mental illness and death among Black people in the North, Smith wrote a brilliant paper in response. In "A Dissertation on the Influence of Climate on Longevity" (1846), published in Hunt's Merchants' Magazine, Smith analyzed the census. He not only proved Calhoun's conclusions wrong but also showed the correct way to analyze data. He showed that Black people in the North lived longer than enslaved people, attended church more, and achieved academically at a similar rate to white people. Based on Smith's findings, John Quincy Adams, acting as a member of the House of Representatives, asked for an investigation of the census results. However, Calhoun appointed someone who supported slavery, and this person decided the census was perfect, so the 1840 census was never corrected.

In 1847, the year the New York Academy of Medicine was founded, two founding members nominated Smith for a fellowship. Because of his race, Smith's nomination was a challenge for the new academy. They wanted to avoid "agitation of the question." After many discussions and delays, the admissions committee eventually did not accept or reject Smith. Instead, they created a unique rule that allowed Smith to be considered "not nominated." This effectively rejected his fellowship.

As Smith started publishing, his work was quickly accepted by newer scientific organizations. In 1852, Smith was invited to be a founding member of the New York Statistics Institute. In 1854, he was elected as a member of the American Geographical Society. This society, founded in New York in 1851, recognized him with an award for one of his articles. He also joined the New-York Historical Society.

Among his many other works supporting abolitionism and dealing with race, Smith was known for writing the introduction to Frederick Douglass's second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855). This introduction showed a new independence in how African Americans wrote about slavery. Earlier works often needed white abolitionists to approve them, as some readers doubted harsh accounts of slavery.

Smith wrote: "The worst of our institutions, in its worst aspect, cannot keep down energy, truthfulness, and earnest struggle for the right."

In the 1850s, Smith also became popular with African-American readers and abolitionist readers of all backgrounds. He wrote regular columns, often weekly, in Frederick Douglass Paper. Smith's comments on African-American culture, politics, literature, and even fashion made him one of the earliest Black public thinkers to become popular in the U.S.

In 1859, Smith published an article using scientific findings to challenge former president Thomas Jefferson's ideas about race. Jefferson had expressed these ideas in his well-known book Notes on the State of Virginia (1785). Dr. Vanessa Northington Gamble, a medical doctor and historian, noted in 2010, "As early as 1859, Dr. McCune Smith said that race was not biological but was a social category." He also wrote about the positive ways that people of African descent would influence U.S. culture and society, including in music, dance, and food. His collected essays, speeches, and letters were published as The Works of James McCune Smith: Black Intellectual and Abolitionist (2006).

Later Years

In 1863, Smith was offered a position as a professor of anthropology at Wilberforce College. This was the first college in the United States owned and operated by African Americans. However, Smith was too ill to take the job. He died two years later, on November 17, 1865, at the age of 52, from congestive heart failure. This was just nineteen days before the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was approved, which officially ended slavery. He was buried at Cypress Hills Cemetery in Brooklyn. Smith was survived by his wife, Malvina, and five children.

Honors and Legacy

In November 2018, the New York Academy of Medicine honored Smith by making him a fellow of the academy. This happened 171 years after he was first nominated and 153 years after his death. At the ceremony, the Academy's President presented a copy of the fellowship certificate to Professor Joanne Edey-Rhodes, who accepted it on behalf of Smith's descendants. In 2019, the academy also showed a portrait of Smith, which was painted by artist Junior Jacques. It is now on display at the academy.

The University of Glasgow, where Smith studied, named its new Learning Hub building the James McCune Smith Learning Hub. It opened to students in early 2021. The university has also created a scholarship and an annual lecture named after Smith.

|

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |