New York City draft riots facts for kids

Quick facts for kids New York City Draft Riots of 1863 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Opposition to the American Civil War | |||

| Date | July 13, 1863 – July 16, 1863 | ||

| Location |

Manhattan, New York, U.S.

|

||

| Caused by | Civil War conscription; racism; competition for jobs between Blacks and whites. | ||

| Resulted in | Riots ultimately suppressed | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 119–120 | ||

| Injuries | 2,000 | ||

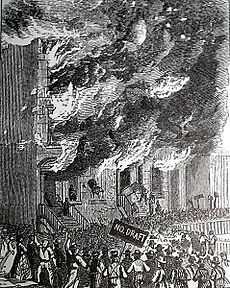

The New York City Draft Riots were a series of violent events that happened in Lower Manhattan, New York City, from July 13 to July 16, 1863. These riots were caused by many white working-class people being unhappy with new laws. These laws made it mandatory for men to join the army and fight in the American Civil War.

These riots are still known as the largest and most racially charged city disturbance in American history. Most of the rioters were Irish working-class men. They did not want to fight in the Civil War. They were also angry that rich men could pay $300 to avoid being drafted. This amount was a lot of money back then. A typical worker earned only $1 or $2 a day.

At first, the protests were about the draft. But they quickly turned into attacks against black people. White rioters attacked black people and their homes all over the city. The official number of people who died was about 119 or 120. The city was in such chaos that Major General John E. Wool said he did not have enough soldiers to declare martial law. Martial law means the military takes control of the city.

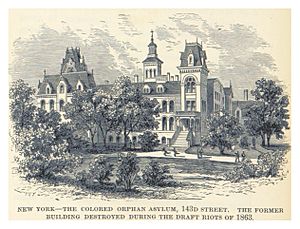

Soldiers did not arrive until the second day of the riots. By then, the angry crowds had already damaged or destroyed many public buildings. They also attacked two churches, homes of people who supported ending slavery, and many black homes. The Colored Orphan Asylum, a home for black children, was burned to the ground. After the riots, many black residents left Manhattan. Many moved to Brooklyn. By 1865, the number of black people in Manhattan was the lowest it had been since 1820.

Contents

Why the Riots Happened

New York City's economy was closely linked to the Southern states. Almost half of its exports in 1822 were cotton shipments. Also, factories upstate used cotton for manufacturing. Because of these strong business ties, some people in New York City supported the South.

New York City was also a popular place for immigrants. In the 1840s and 1850s, many immigrants came from Ireland and Germany. By 1860, about 25% of New York City's population was German-born. Many of them did not speak English. Newspapers at the time often wrote stories that made black people look bad. They also made fun of black people wanting equal rights.

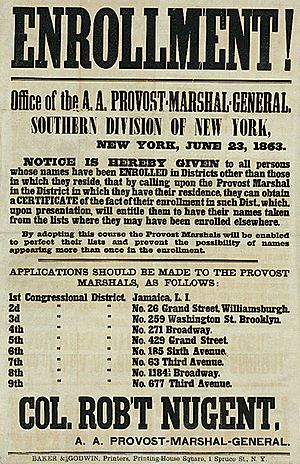

The Democratic Party worked to help immigrants become U.S. citizens so they could vote. They especially encouraged Irish immigrants. In March 1863, Congress passed the Enrollment Act. This law started the first draft in the United States. New citizens in New York City were now expected to join the army. Black men were not included in the draft because they were not seen as citizens. Rich white men could pay to avoid the draft.

The Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863 also worried many white working-class people in New York. They feared that freed slaves would move to the city. This would mean more competition for jobs. There were already problems between black and white workers since the 1850s. This was especially true at the docks, where they competed for low-paying jobs. In March 1863, white dockworkers attacked about 200 black men. They refused to work with them.

The Riots Begin

The first draft drawing happened peacefully in Manhattan on July 11, 1863. But the second drawing, on Monday, July 13, 1863, was different. This was ten days after the Union victory at Gettysburg.

Monday: The First Day of Violence

At 10 a.m., about 500 angry people attacked the draft office. This office was at Third Avenue and 47th Street. The crowd was led by volunteer firefighters. They threw large stones through windows and broke down doors. Then they set the building on fire. When firefighters arrived, rioters broke their vehicles. Others killed horses pulling streetcars and smashed the cars. To stop news of the riot from spreading, they cut telegraph lines.

The New York State Militia had been sent to help Union troops at Gettysburg. So, the local New York Metropolitan Police Department was the only force available. Police Superintendent John Alexander Kennedy came to check on the situation. Even though he was not in uniform, the mob recognized him and attacked him. Kennedy was badly hurt. His face was bruised, his eye injured, and his hand cut.

Police officers tried to stop the crowd with their clubs and revolvers. But they were greatly outnumbered. They could not stop the riots. However, they did manage to keep the rioting out of Lower Manhattan below Union Square. Some soldiers from the U.S. Army Invalid Corps tried to stop the mob with gunfire. But they were also overwhelmed. Many were injured, and one soldier went missing.

The Bull's Head hotel on 44th Street was burned because it would not give alcohol to the rioters. The mayor's home on Fifth Avenue was saved by Judge George G. Barnard. But the crowd of about 500 then moved to other places to loot. Police stations and other buildings were attacked and set on fire. The office of The New York Times was also a target. Staff members using Gatling guns, including the founder Henry Jarvis Raymond, turned the mob away.

Some firefighters were sympathetic to the rioters because they had also been drafted. The New-York Tribune newspaper office was looted and burned. Police arrived and put out the flames, scattering the crowd. Later that day, authorities shot and killed a man as a crowd attacked an armory. The mob broke all the windows with paving stones. The mob also attacked and killed many black civilians. They destroyed their homes and businesses. This included James McCune Smith's pharmacy, which was believed to be the first owned by a black man in the U.S.

Near the midtown docks, old tensions exploded. White dockworkers attacked and destroyed dance halls and homes that served black people. They even stripped the clothes off white owners of these businesses.

Tuesday: Governor Arrives

Heavy rain on Monday night helped put out the fires. It also sent rioters home. But the crowds returned the next day. Rioters burned down the home of Abby Gibbons, a prison reformer. They also attacked white people who supported mixing races. This included Ann Derrickson and Ann Martin, two white women married to black men.

Governor Horatio Seymour arrived on Tuesday. He spoke at City Hall. He tried to calm the crowd by saying the draft law was against the Constitution. General John E. Wool brought about 800 soldiers and Marines from nearby forts. He also ordered militias to return to New York.

Wednesday: Draft Postponed

The situation improved on July 15. The draft was officially postponed. When this news appeared in newspapers, some rioters stayed home. But some of the militias began to return. They used strong force against the remaining rioters. The rioting also spread to Brooklyn and Staten Island.

Thursday: Order Restored

Order began to return on July 16. The New York State Militia and some federal troops came back to New York. There were several thousand militia and federal troops in the city. A final fight happened that evening. About twelve people died on this last day of the riots.

Newspapers reported that gang members from Baltimore and Philadelphia had come to New York. They joined local gangs like the Dead Rabbits.

Aftermath and Impact

The exact number of deaths during the New York draft riots is not fully known. But historian James M. McPherson says 119 or 120 people were killed. Violence against black men was especially harsh near the docks. In total, eleven black men were killed over five days.

Many people were injured. The most reliable estimates say at least 2,000 people were hurt. Total property damage was about $1 to $5 million. This was a huge amount of money at the time. The city later paid back a quarter of this amount.

Historian Samuel Eliot Morison said the riots were like a victory for the Confederacy. About 4,000 federal troops had to be taken away from the Gettysburg Campaign. These troops could have helped chase the Confederate army. During the riots, landlords feared their buildings would be destroyed. So, they forced black residents out of their homes. Because of the violence, hundreds of black people left New York. They moved to places like Williamsburg, Brooklyn, or New Jersey.

Wealthy white people in New York helped black riot victims. They helped them find new jobs and homes. Groups like the Union League Club gave almost $40,000 to 2,500 victims. By 1865, the black population in the city had dropped to under 10,000. This was the lowest since 1820. The riots changed who lived in the city. White residents gained more control in the workplace. They became "unequivocally divided" from the black population.

The government started the draft again on August 19. It finished within 10 days without more problems. Fewer men were drafted than white workers had feared. Out of 750,000 men chosen nationwide, only about 45,000 were sent to active duty.

While the riots mainly involved the white working class, rich New Yorkers had mixed feelings about the draft. Many wealthy Democratic businessmen wanted the draft to be called unconstitutional. Other Democrats helped pay the fees for those who were drafted.

In December 1863, the Union League Club recruited over 2,000 black soldiers. They trained and equipped them. In March 1864, these soldiers marched through the city in a parade. A crowd of 100,000 people watched.

New York's support for the Union cause continued. New York banks helped pay for the Civil War. The state's industries produced more than all the Southern states combined. By the end of the war, over 450,000 soldiers, sailors, and militia had joined from New York State. This was the most populous state at the time. A total of 46,000 military men from New York State died during the war. Most died from disease, not wounds.

Order of Battle: Forces Involved

New York Metropolitan Police Department

The New York Metropolitan Police Department was led by Superintendent John Alexander Kennedy. When Kennedy was badly hurt, Commissioners Thomas Coxon Acton and John G. Bergen took command. Four police officers died during the riots.

| Precinct | Commander | Location | Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Precinct | Captain Jacob B. Warlow | 29 Broad Street | 4 Sergeants, 63 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 2nd Precinct | Captain Nathaniel R. Mills | 49 Beekman Street | 4 Sergeants, 60 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 3rd Precinct | Captain James Greer | 160 Chambers Street | 3 Sergeants, 64 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 4th Precinct | Captain James Bryan | 9 Oak Street | 4 Sergeants, 70 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 5th Precinct | Captain Jeremiah Petty | 49 Leonard Street | 4 Sergeants, 61 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 6th Precinct | Captain John Jourdan | 9 Franklin Street | 4 Sergeants, 63 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 7th Precinct | Captain William Jamieson | 247 Madison Street | 4 Sergeants, 52 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 8th Precinct | Captain Morris DeCamp | 126 Wooster Street | 4 Sergeants, 52 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 9th Precinct | Captain Jacob L. Sebring | 94 Charles Street | 4 Sergeants, 51 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 10th Precinct | Captain Thaddeus C. Davis | Essex Market | 4 Sergeants, 62 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 11th Precinct | Captain John I. Mount | Union Market | 4 Sergeants, 56 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 12th Precinct | Captain Theron R. Bennett | 126th Street (near Third Avenue) | 5 Sergeants, 41 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 13th Precinct | Captain Thomas Steers | Attorney Street (at corner of Delancey Street) | 4 Sergeants, 63 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 14th Precinct | Captain John J. Williamson | 53 Spring Street | 4 Sergeants, 58 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 15th Precinct | Captain Charles W. Caffery | 220 Mercer Street | 4 Sergeants, 69 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 16th Precinct | Captain Henry Hedden | 156 West 20th Street | 4 Sergeants, 50 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 17th Precinct | Captain Samuel Brower | First Avenue (at the corner of Fifth Street) | 4 Sergeants, 56 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 18th Precinct | Captain John Cameron | 22nd Street (near Second Avenue) | 4 Sergeants, 74 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 19th Precinct | Captain Galen T. Porter | 59th Street (near Third Avenue) | 4 Sergeants, 49 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 20th Precinct | Captain George W. Walling | 212 West 35th Street | 4 Sergeants, 59 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 21st Precinct | Sergeant Cornelius Burdick (acting Captain) | 120 East 31st Street | 4 Sergeants, 51 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 22nd Precinct | Captain Johannes C. Slott | 47th Street (between Eighth and Ninth Avenues) | 4 Sergeants, 54 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 23rd Precinct | Captain Henry Hutchings | 86th Street (near Fourth Avenue) | 4 Sergeants, 42 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 24th Precinct | Captain James Todd | New York waterfront | 2 Sergeants and 20 Patrolmen |

| 25th Precinct | Captain Theron Copeland | 300 Mulberry Street | 1 Sergeant, 38 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 26th Precinct | Captain Thomas W. Thorne | City Hall | 1 Sergeant, 66 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 27th Precinct | Captain John C. Helme | 117 Cedar Street | 4 Sergeants, 52 Patrolmen, and 3 Doormen |

| 28th Precinct | Captain John F. Dickson | 550 Greenwich Street | 4 Sergeants, 48 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 29th Precinct | Captain Francis C. Speight | 29th Street (near Fourth Avenue) | 4 Sergeants, 82 Patrolmen, and 3 Doormen |

| 30th Precinct | Captain James Z. Bogart | 86th Street and Bloomingdale Road | 2 Sergeants, 19 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

| 32nd Precinct | Captain Alanson S. Wilson | Tenth Avenue and 152nd Street | 4 Sergeants, 35 Patrolmen, and 2 Doormen |

New York State Militia

The New York State Militia was led by Major General Charles W. Sandford.

| Unit | Commander | Complement |

|---|---|---|

| 65th Regiment | Colonel William F. Berens | 401 |

| 74th Regiment | Colonel Watson A. Fox | |

| 20th Independent Battery | Captain B. Franklin Ryer |

Union Army Troops

Major General John E. Wool was in charge of the Department of the East in New York. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton sent five regiments from Gettysburg to help. By the end of the riots, over 4,000 soldiers were in the city.

| Unit | Commander | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Invalid Corps | Over 16 injured; 1 killed, 1 missing | |

| 26th Michigan Volunteer Infantry Regiment | Colonel Judson S. Farrar | |

| 5th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment | Colonel Cleveland Winslow | 50 men from his regiment and 200 volunteers |

| 7th New York National Guard Regiment | Colonel Marshall Lefferts | 800 men; recalled from Gettysburg |

| 8th New York National Guard Regiment | Brigadier General Charles C. Dodge | 150 men |

| 9th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment | Colonel Edward E. Jardine (wounded) | 200 volunteers from this regiment |

| 11th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment | Colonel Henry O'Brien (killed) | Colonel O'Brien was recruiting at the time |

| 11th U.S. Regular Infantry Regiment | Colonel Erasmus D. Keyes | Sent to New York City to keep order |

| 13th New York Volunteer Cavalry Regiment | Colonel Charles E. Davies | 2 fatalities during the riots |

| 14th New York Volunteer Cavalry Regiment | Colonel Thaddeus P. Mott | All cavalry regiments were later led by General Judson Kilpatrick |

| 17th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment | Major T. W. C. Grower | 4 losses: 1 killed, 3 wounded |

| 22nd New York National Guard Regiment | Colonel Lloyd Aspinwall | |

| 47th New York State Militia/National Guard Regiment | Colonel Jeremiah V. Messerole | |

| 152nd New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment | Colonel Alonso Ferguson | |

| 14th Indiana Infantry Regiment | Colonel John Coons |

The Riots in Books and Movies

The New York City Draft Riots have been shown in many books and films.

Books about the Riots

- Wilderness: A Tale of the Civil War (1961) by Robert Penn Warren

- The Banished Children of Eve, A Novel of Civil War New York (1995) by Peter Quinn

- My Notorious Life: A Novel (2014) by Kate Manning

- On Secret Service (2000) by John Jakes

- Paradise Alley (2003) by Kevin Baker

- New York: the Novel (2009) by Edward Rutherfurd

- Grant Comes East (2004) by Newt Gingrich

- Last Descendants (2016) by Matthew J. Kirby

- Riot (2009) by Walter Dean Myers

- A Wish After Midnight (2008) by Zetta Elliott, a story set in Brooklyn, switching between the early 21st century and 1863.

- Libertie (2021) by Kaitlyn Greenidge

- Moon and the Mars (2021) by Kia Corthron

Television, Theatre, and Film

- The musical Maggie Flynn (1968) was set in a home for black children, similar to the Colored Orphan Asylum.

- Gangs of New York (2002) is a film directed by Martin Scorsese. It shows a made-up version of the New York Draft Riots.

- Paradise Square (2018) is a musical that shows the events leading up to and including the riots.

- Copper (2012) is a TV show about New York City in 1864/1865. It includes flashbacks to the riots.

See also

In Spanish: Draft Riots para niños

In Spanish: Draft Riots para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |