Cuneiform facts for kids

Cuneiform script is one of the oldest ways of writing that we know about. People used special tools called styluses to make wedge-shaped marks on soft clay tablets. The word cuneiform means "wedge-shaped." It comes from the Latin words cuneus (wedge) and forma (shape).

This writing system first appeared in a place called Sumer around 3,400 BC. At first, cuneiform used simple pictures, like pictographs. Over time, these pictures became simpler and more like abstract shapes. The number of different signs also got smaller. Early on, there were about 1,000 signs, but later there were around 400. Cuneiform used a mix of signs that stood for sounds, syllables, and whole words.

The original Sumerian cuneiform was used by many other groups. These included the Akkadians, Eblaites, Elamites, and Hittites. It even inspired other alphabets like Ugaritic and Old Persian. However, cuneiform slowly started to disappear. The Phoenician alphabet began to replace it during the Neo-Assyrian Empire. By about 200 BC, no one used cuneiform anymore. People forgot how to read it until experts started to figure it out in the 1800s.

Contents

History of Cuneiform Writing

Writing first started after people learned to make pottery. During the Neolithic period, people used small clay tokens. These tokens helped them keep track of things like how many animals or goods they had. Some experts now have different ideas about whether these tokens led directly to writing.

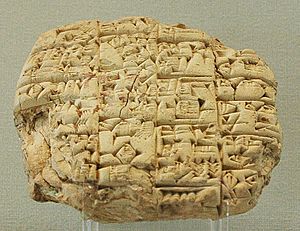

At first, these tokens were pressed onto the outside of round clay envelopes. Then, they were stored inside them. Later, flat clay tablets replaced the tokens. People used a stylus to write signs directly on these tablets. The first clear examples of writing come from a city called Uruk. This was around 3,300 BC. Soon after, writing appeared in other parts of the Near-East.

An old poem from Mesopotamia tells a story about how writing began. It says the messenger couldn't remember a long message. So, the Lord of Kulaba pressed words onto a clay tablet. Before that, no one had put words on clay.

Cuneiform writing was used for over 3,000 years. It went through many changes. The very last cuneiform tablet we know of is from 79 AD. Eventually, writing systems that used alphabets completely replaced cuneiform. All knowledge of how to read it was lost. But in the 1800s, experts called Assyriologists successfully figured out how to read it again. This happened by 1857.

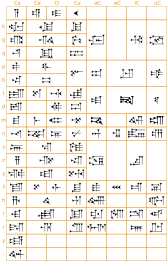

How Cuneiform Signs Changed

Cuneiform script changed a lot over more than 2,000 years. For example, the sign for "head" looked very different over time.

- Around 3000 BC, it was a simple picture.

- By 2800–2600 BC, the picture was rotated.

- Around 2600 BC, it became more abstract in stone carvings.

- At the same time, when written on clay, it looked a bit different.

- By the late 3rd millennium BC, it was even simpler.

- In the early 2nd millennium BC, it became more angular.

- By the early 1st millennium BC, it was very simplified. This was how it looked until it stopped being used.

Early Sumerian Pictures (around 3300 BC)

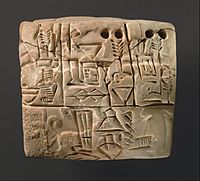

Cuneiform started from pictographic "proto-writing." This was a system of pictures used for counting in the Near East. We are still debating what these tokens meant and how they were used. They were used from about 9000 BC and sometimes even later. Early tokens shaped like animals, with numbers, were found in Tell Brak. These date to the mid-4th millennium BC. Some think these token shapes were the basis for some Sumerian pictographs.

The "proto-literate" period in Mesopotamia was from about 3500 to 3200 BC. The first clear written documents are from the Uruk IV period, around 3,300 BC. More tablets were found in Uruk III, Jemdet Nasr, and other places. These date up to about 2,900 BC.

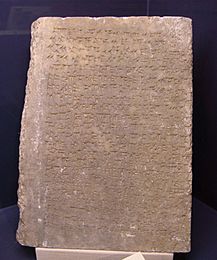

At first, pictographs were drawn on clay tablets. They were in vertical columns. People used a sharpened reed stylus or carved them into stone. This early style did not have the famous wedge shape. Most early cuneiform records were for keeping accounts. The list of early cuneiform signs has changed as new texts are found. Currently, there are 705 signs.

Certain signs were used to show names of gods, countries, or cities. These were called determinatives. They were Sumerian signs added to help the reader understand. Proper names were usually written using only "logographic" signs, which stood for whole words.

Archaic Cuneiform (around 2900 BC)

The first tablets with writing were only pictographic. This makes it hard to know what language they were written in. Many languages have been suggested, but Sumerian is usually assumed. Later tablets, after about 2900 BC, started to use parts that stood for syllables. These clearly show the structure of the Sumerian language. The first tablets using syllables are from around 2800 BC. Experts agree these are clearly in Sumerian.

This was when some picture elements started to be used for their sound value. This allowed people to write down abstract ideas or personal names. Many pictographs began to lose their original meaning. One sign could have different meanings depending on the situation. The number of signs went down from about 1,500 to 600. Writing became more focused on sounds. Determinative signs were brought back to make things clear. True cuneiform writing developed from the simpler picture system around this time. Historians call this the Early Bronze Age II period.

The earliest known Sumerian king whose name is on cuneiform tablets is Enmebaragesi of Kish. He lived around 2600 BC. Records from later kings are more complete. By the time of Sargon, it was common for cities to date documents by year-names. These names celebrated the king's achievements.

Cuneiform and Hieroglyphs

Some experts believe that Egyptian hieroglyphs appeared a little after Sumerian writing. They think hieroglyphs were probably invented because of Sumerian influence. It is likely that the general idea of writing down words came to Egypt from Mesopotamia. There are many signs of connections between Egypt and Mesopotamia when writing was invented. Most ideas about how writing developed place Sumerian writing before Egyptian hieroglyphs. This suggests Sumerian writing influenced Egyptian. However, there is no direct proof of this. So, we cannot say for sure how hieroglyphs started in ancient Egypt. Others believe that writing in Egypt might have developed on its own.

Early Dynastic Cuneiform (around 2500 BC)

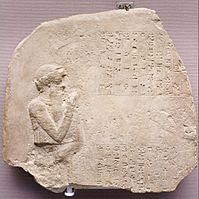

Early cuneiform was made using a pointed stylus. This was sometimes called "linear cuneiform." Many early inscriptions, especially those on stone, continued to use this linear style until about 2000 BC.

In the mid-3rd millennium BC, a new stylus with a wedge-shaped tip was introduced. This stylus was pushed into the clay. This made writing faster and easier, especially on soft clay. Writers could make different marks with one tool. For numbers, a round-tipped stylus was used at first. Then, the wedge-tipped stylus became common for everything.

People wrote from top to bottom and right to left. Cuneiform clay tablets could be baked in kilns. This made them hard and permanent. Or, they could be left moist and reused if they weren't needed forever. This is why many surviving cuneiform tablets were preserved by accident.

The spoken language had many words that sounded the same. For example, "life" and "arrow" sounded similar. At first, they were written with the same symbol. When the Akkadian language became popular, some signs changed. They went from being pictures to standing for syllables. This made writing clearer. So, the sign for "arrow" became the sign for the sound "ti."

Words that sounded alike would have different signs. For example, the sound [ɡu] had fourteen different symbols. But words with similar meanings but different sounds were written with the same symbol. For example, 'tooth,' 'mouth,' and 'voice' were all written with the symbol for "voice." To be more exact, scribes started adding to signs or combining two signs. They used geometric patterns or other cuneiform signs.

Over time, cuneiform became very complex. The difference between a picture sign and a syllable sign became unclear. Some symbols had too many meanings. So, symbols were put together to show both the sound and the meaning of a word. For example, the word 'raven' had the same symbol as 'soap' and a city name. Scribes added sounds before and after the symbol. Finally, the symbol for 'bird' was added to make sure it was read correctly.

For unknown reasons, cuneiform pictures were rotated 90 degrees counterclockwise. This put them on their side. This change happened just before the Akkadian period. This was during the time of the Uruk ruler Lugalzagesi (around 2294–2270 BC). The vertical style was still used for important stone carvings until the mid-2nd millennium.

Written Sumerian was used by scribes until the first century AD. The spoken language died out between about 2100 and 1700 BC.

Sumero-Akkadian Cuneiform

(around 2200 BC)

The old cuneiform script was taken up by the Akkadian Empire starting in the 23rd century BC. The Akkadian language was very different from Sumerian. It was a Semitic language. The Akkadians found a way to write their language using the Sumerian phonetic signs (signs that stood for sounds). However, they kept some Sumerian characters for their picture meaning. For example, the character for "sheep" was kept, but it was now pronounced immerū in Akkadian, instead of the Sumerian "udu-meš."

The Semitic languages used many signs that were changed or shortened. This was because the Sumerian system of syllables was not natural for Semitic speakers. From the start of the Middle Bronze Age (20th century BC), the script changed. It adapted to different Akkadian dialects like Old Akkadian, Babylonian, and Assyrian. At this point, the old pictograms became very abstract. They were made of only five basic wedge shapes: horizontal, vertical, two diagonals, and a small mark called a Winkelhaken.

Most later versions of Sumerian cuneiform kept some parts of the original script. Written Akkadian included phonetic symbols from the Sumerian system. It also had logograms, which were signs for whole words. Many signs had more than one meaning. They could be a syllable or a whole word. This complex system is a bit like Old Japanese. Old Japanese was written using Chinese characters. Some characters were used for their meaning, and others for their sound.

Elamite Cuneiform

Elamite cuneiform was a simpler version of Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform. It was used to write the Elamite language in the area that is now Iran. Elamite cuneiform sometimes competed with other local scripts. The earliest known Elamite cuneiform text is a treaty from 2200 BC. It was between Akkadians and Elamites. But some think it might have been used since 2500 BC. The tablets are not well preserved, so only parts can be read. It seems to be a treaty between the Akkad king Nāramsîn and the Elamite ruler Hita.

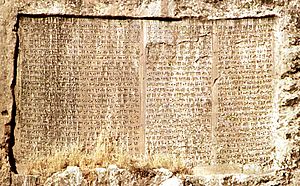

The most famous Elamite writings are found in the trilingual Behistun inscriptions. These were made by the Achaemenid kings. Like the Rosetta Stone, these inscriptions were in three different writing systems. The first was Old Persian, which was figured out in 1802. The second, Babylonian cuneiform, was deciphered soon after. Because Elamite is different from its neighboring Semitic languages, it took longer to decipher. This happened in the 1840s. Even today, it is hard to study Elamite because there are not many sources.

Assyrian Cuneiform

(around 650 BC)

This "mixed" way of writing continued until the end of the Babylonian and Assyrian empires. Sometimes, people preferred to write words out fully. But even then, the Babylonian system still mixed whole-word signs and sound-based signs.

Hittite cuneiform was an adaptation of Old Assyrian cuneiform from around 1800 BC. It was used for the Hittite language. When cuneiform was adapted for Hittite, Akkadian whole-word spellings were added. So, we don't know the pronunciations of many Hittite words that were written with logograms.

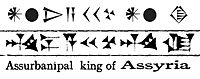

In the Iron Age (around 10th to 6th centuries BC), Assyrian cuneiform became even simpler. The characters were the same as Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform. But their design used more wedges and square angles. This made them much more abstract. The pronunciation of the characters changed to fit the Assyrian dialect of the Akkadian language.

-

"Assurbanipal King of Assyria"

Aššur-bani-habal šar mat Aššur KI

Same characters, in the classical Sumero-Akkadian script of circa 2000 BC (top), and in the Neo-Assyrian script of the Rassam cylinder, 643 BC (bottom). -

The Rassam cylinder with translation of a part about the Assyrian conquest of Egypt by Ashurbanipal against "Black Pharaoh" Taharqa, 643 BC

From the 6th century BC, the Akkadian language was used less. Aramaic, written with the Aramaean alphabet, became more common. But Neo-Assyrian cuneiform was still used in literature. It was used until the time of the Parthian Empire (250 BC–226 AD). The last known cuneiform writing, about astronomy, was written in 75 AD. People might have been able to read cuneiform until the third century AD.

Scripts that Came from Cuneiform

Old Persian Cuneiform (5th century BC)

(around 500 BC)

Cuneiform was complex, so simpler versions were created. Old Persian cuneiform was developed by Darius the Great in the 5th century BC. It had its own simple cuneiform characters. Most experts think this writing system was invented independently. It doesn't seem to be directly connected to other cuneiform systems of that time.

It was a semi-alphabetic system. It used fewer wedge strokes than Assyrian cuneiform. It also had a few logograms for common words like "god," "king," or "country." This almost purely alphabetical form of cuneiform (36 sound characters and 8 word signs) was made and used by the early Achaemenid rulers. This was from the 6th to the 4th century BC.

Because it was simple and logical, Old Persian cuneiform was the first to be deciphered by modern scholars. Georg Friedrich Grotefend started this in 1802. Then, old inscriptions written in two or three languages helped decipher the other, much older and more complicated cuneiform scripts. This went all the way back to the Sumerian script from the 3rd millennium BC.

Ugaritic

Ugaritic was written using the Ugaritic alphabet. This was a standard Semitic style alphabet (an abjad). It was written using the cuneiform method.

Images for kids

-

Cuneiform inscriptions recorded by Jean Chardin in Persepolis in 1674 (1711 edition)

-

Relying on deductions only, and without knowing the actual script or language, Grotefend obtained a near-perfect translation of the Xerxes inscription (Niebuhr inscription 2): "Xerxes the strong King, King of Kings, son of Darius the King, ruler of the world" ("Xerxes Rex fortis, Rex regum, Darii Regis Filius, orbis rector", right column). The modern translation is: "Xerxes the Great King, King of Kings, son of Darius the King, an Achaemenian".

-

The quadrilingual hieroglyph-cuneiform "Caylus vase" in the name of Xerxes I confirmed the decipherment of Grotefend once Champollion was able to read Egyptian hieroglyphs.

-

Once Old Persian had been fully deciphered, the trilingual Behistun Inscription permitted the decipherment of two other cuneiform scripts: Elamite and Babylonian.

-

Cuneiform sign "EN", for "Lord" or "Master": evolution from the pictograph of a throne circa 3000 BC, followed by simplification and rotation down to circa 600 BC.

-

Cuneiform writing in Ur, southern Iraq

-

The central element of the GigaMesh Software Framework logo is the sign 𒆜 (kaskal) meaning "street" or "road junction", which symbolizes the intersection of the humanities and computer science. The name GigaMesh is an intentional reference to the legendary Gilgamesh from Mesopotamian folklore.

See also

In Spanish: Escritura cuneiforme para niños

In Spanish: Escritura cuneiforme para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |