Ashurbanipal facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ashurbanipal |

|

|---|---|

|

|

Ashurbanipal, closeup from the Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal

|

|

| King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire | |

| Reign | 669–631 BC |

| Predecessor | Esarhaddon |

| Successor | Ashur-etil-ilani |

| Born | c. 685 BC |

| Died | 631 BC (aged c. 54) |

| Spouse | Libbali-sharrat |

| Issue | Ashur-etil-ilani Sinsharishkun Ninurta-sharru-usur |

| Akkadian | Aššur-bāni-apli |

| Dynasty | Sargonid dynasty |

| Father | Esarhaddon |

| Mother | Esharra-hammat (?) |

Ashurbanipal (Akkadian: Aššur-bāni-apli, meaning "Ashur is the creator of the heir") was a powerful king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. He ruled from 669 BCE until his death in 631 BCE. Many people remember him as the last truly great king of Assyria.

Ashurbanipal's father, Esarhaddon, chose him to be the next king around 673 BCE. This was a bit unusual because Ashurbanipal had an older brother, Shamash-shum-ukin. To avoid problems, Esarhaddon made Shamash-shum-ukin the king of Babylonia. Both brothers became kings when their father died in 669 BCE. However, Shamash-shum-ukin was still under Ashurbanipal's control.

Early in his reign, Ashurbanipal fought many battles in Egypt. His father had conquered Egypt, but it kept rebelling. Ashurbanipal also fought against Elam, an old enemy of Assyria. Later, his brother Shamash-shum-ukin rebelled too. Ashurbanipal defeated Elam in several wars. He also defeated Shamash-shum-ukin, who died during a siege of Babylon in 648 BCE. We don't know much about the end of Ashurbanipal's reign because there are not many records left.

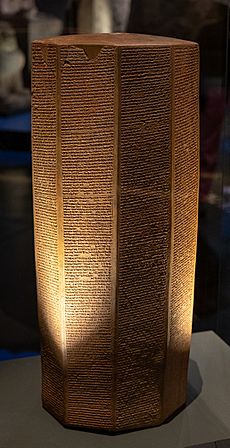

Ashurbanipal is famous today for his love of books and art. He was very interested in the ancient stories and writings of Mesopotamia. During his long rule, he used his empire's wealth to build the Library of Ashurbanipal. This library was a huge collection of texts. It might have had over 100,000 texts! It was the biggest library of its kind until the Library of Alexandria was built much later. More than 30,000 texts from his library have survived. They teach us a lot about ancient Mesopotamian language, religion, stories, and science. The art made during his time was also new and exciting.

In later Greek and Roman stories, Ashurbanipal was called Sardanapalus. These stories often wrongly described him as a weak and lazy king who caused his empire to fall. Modern historians disagree about whether Ashurbanipal was to blame for Assyria's fall, which happened only about 20 years after he died. Ashurbanipal was known for being a very tough Assyrian king. His armies were successful and traveled further than ever before. However, some of his wars didn't help Assyria in the long run. For example, he lost control of Egypt. His wars in Arabia used up a lot of resources but didn't lead to lasting control. Also, his harsh treatment of Babylon after defeating Shamash-shum-ukin made people in southern Mesopotamia dislike Assyria even more. This might have helped the Neo-Babylonian Empire rise to power after Ashurbanipal's death.

Contents

Becoming King

How Ashurbanipal Became Heir

Ashurbanipal was born around 685 BCE. He was one of the sons of King Esarhaddon. Becoming king was not simple for Ashurbanipal. He was probably his father's fourth son. His older brothers included Sin-nadin-apli, Shamash-shum-ukin, and Shamash-metu-uballit. He also had an older sister, Serua-eterat.

In 674 BCE, his oldest brother, Sin-nadin-apli, died unexpectedly. Esarhaddon wanted to avoid a fight over who would be king next. So, he quickly made new plans. Esarhaddon decided that Shamash-shum-ukin would be the heir to Babylonia. Ashurbanipal would be the heir to Assyria. He called them "equal brothers." The third son, Shamash-metu-uballit, was passed over, maybe because he was often sick.

Esarhaddon's choice was surprising. His own father, Sennacherib, had done something similar. Sennacherib had chosen Esarhaddon over an older son, which led to a civil war. It's not clear why Esarhaddon made the same choice. Giving one son Assyria and another Babylonia was a new idea. Before, the Assyrian king ruled both. Maybe Esarhaddon hoped this would stop jealousy between his sons. One idea is that Ashurbanipal and Shamash-shum-ukin had different mothers. Ashurbanipal might have been the son of an Assyrian woman, and Shamash-shum-ukin the son of a Babylonian woman. This might have made it difficult for Shamash-shum-ukin to rule Assyria.

After Esarhaddon made his decision, the two princes went to the Assyrian capital, Nineveh. In May 672 BCE, they celebrated with foreign leaders and Assyrian nobles. Ashurbanipal's name, Aššur-bāni-apli, means "Ashur is the creator of the heir." He probably got this name around this time. We don't know his name before he became crown prince. It was also around this time that Ashurbanipal married his future queen, Libbali-sharrat.

Crown Prince and Becoming King

After being named crown prince, Ashurbanipal moved into the "House of Succession." This was the palace for the crown prince. Here, he trained for his royal duties. He learned hunting, riding, scholarship, archery, and military skills. His father, Esarhaddon, was often sick. So, Ashurbanipal and Shamash-shum-ukin took on many duties in the last years of their father's rule. This helped them gain real experience. Letters show that Ashurbanipal was involved in Assyria's spy network. He gathered information on enemies for his father.

Ashurbanipal became king of Assyria in late 669 BCE, after Esarhaddon died. He had only been crown prince for three years. When he became king, he was likely the most powerful person in the world. But there were some worries. His grandmother, Naqi'a, made a special treaty. It forced the royal family, nobles, and all of Assyria to promise loyalty to Ashurbanipal. However, there was no strong opposition to him becoming king.

Shamash-shum-ukin became king of Babylon the next spring. Ashurbanipal showed goodwill by returning the important Statue of Marduk to Babylon. This statue had been stolen by Sennacherib 20 years earlier. Shamash-shum-ukin ruled Babylon for 16 years. He seemed to live peacefully with his younger brother at first. But they often disagreed about how much power Shamash-shum-ukin really had.

Treaties made by Esarhaddon were unclear about the brothers' relationship. Ashurbanipal was clearly the main heir. Shamash-shum-ukin was supposed to promise loyalty to him. But other parts of the treaties said Ashurbanipal should not interfere in Shamash-shum-ukin's affairs. This suggests Esarhaddon wanted them to be more equal. Ashurbanipal might have ignored his father's wishes to gain more power. He might have feared that a strong older brother could threaten his rule.

Military Campaigns

Wars in Egypt

Ashurbanipal's father, Esarhaddon, had conquered Egypt in 671 BCE. This was a huge achievement, making the Assyrian Empire its largest ever. But Assyrian control over Egypt was weak. The Egyptian pharaoh, Taharqa, escaped to Nubia and planned to take back his land. Esarhaddon had left Assyrian soldiers in Egyptian cities and appointed local Egyptian nobles to rule.

In 669 BCE, Taharqa returned and led a revolt against Assyria. Esarhaddon set out to fight him but died on the way. Ashurbanipal was busy becoming king, so Assyria didn't respond right away. This encouraged many Egyptian rulers to join the revolt. When Ashurbanipal heard about a terrible attack on the Assyrian soldiers in Memphis, he sent an army to stop the uprising.

The Assyrian army gathered taxes from the lands they passed through on their way to Egypt. Many local rulers, like Manasseh of Judah, also sent soldiers and supplies to help the Assyrians. The Assyrian army and its allies fought their way through Egypt. They won a major battle at Kar-Banitu. Assyrian records say that after this defeat, Taharqa fled to Nubia again. Soon after, the Assyrian army captured Memphis. Some Egyptian leaders who had stayed in Memphis were taken to Assyria. They had to promise loyalty again. Surprisingly, some, like Necho I, were allowed to return and rule their cities.

After Taharqa died in 664 BCE, his nephew Tantamani became pharaoh. Tantamani invaded Egypt, quickly took control of Thebes, and marched toward Memphis. Ashurbanipal sent his army again. According to Ashurbanipal, Tantamani fled south as soon as the Assyrian army entered Egypt. To punish Thebes for supporting Tantamani, the Assyrians captured and heavily looted the city. This was a terrible disaster for Thebes. The city might have been saved from total destruction by its governor, Mentuemhat. Tantamani was not chased beyond Egypt's border. When the Assyrian army returned to Nineveh, treasures from Thebes were shown off in the streets. Many valuable items were melted down for Ashurbanipal's building projects.

Early Wars with Elam

In 665 BCE, the Elamite king Urtak attacked Babylonia by surprise. Urtak had been peaceful with Esarhaddon. Ashurbanipal's forces drove Urtak back to Elam, where he died soon after. Teumman became the new Elamite king. He was not related to Urtak and had to kill his rivals to secure his rule. Three of Urtak's sons escaped to Assyria. Ashurbanipal protected them, even though Teumman demanded they be returned.

After the victory over Elam in 665, Ashurbanipal had to deal with revolts inside his own empire. Bel-iqisha, a leader of the Gambulians (an Aramean tribe) in Babylonia, rebelled. He was thought to have helped the Elamite invasion. His revolt didn't cause much damage, and he died soon after. His son, Dunanu, surrendered to Ashurbanipal in 663 BCE.

After a long period of peace, Teumman attacked Babylonia again in 653 BCE. Shamash-shum-ukin did not have a large army, so he couldn't defend Babylonia alone. He had to ask Ashurbanipal for help. Ashurbanipal's army first went south to secure the city of Der. Teumman marched to meet the Assyrians but then retreated to his capital, Susa. The final battle, the Battle of Ulai, happened near Susa. It was a major Assyrian victory. Teumman was killed in the battle. Ashurbanipal then put two of Urtak's sons on the throne in Elam. This weakened Elam's power and its ability to fight Assyria.

Dunanu, who had joined the Elamites, was captured and executed. The Gambulians were severely punished by Ashurbanipal's army. Their capital, Shapibel, was flooded, and many people were killed. Ashurbanipal appointed a new Gambulian leader, Rimutu, who agreed to pay a large amount of tribute.

Diplomacy and Attacks on Assyria

The Cimmerians, a nomadic people from the north, had invaded Assyria during Esarhaddon's reign. After Esarhaddon defeated them, the Cimmerians attacked Lydia in western Anatolia. Lydia was ruled by Gyges. Gyges asked Ashurbanipal for help. The Assyrians didn't even know Lydia existed! After they managed to communicate, the Cimmerian invasion of Lydia was defeated around 665 BCE. Two Cimmerian leaders were imprisoned in Nineveh, and Ashurbanipal's forces gained much treasure. We don't know how much the Assyrian army helped. Gyges seemed unhappy with the help, because 12 years later he broke his alliance with Ashurbanipal and allied with Egypt. Ashurbanipal then cursed Gyges. When Lydia was overrun by enemies around 652–650 BCE, Assyria celebrated.

While the Assyrian army was fighting in Elam, an alliance of Persians, Cimmerians, and Medes marched on Nineveh. They reached the city walls. To fight them off, Ashurbanipal called on his Scythian allies. They successfully defeated the enemy army. The Median king, Phraortes, is thought to have died in this battle. This attack is not well documented.

After Gyges died around 652 BCE, his son Ardys became king. The Cimmerians invaded Lydia again and captured most of the kingdom. Ardys also asked Ashurbanipal for help. He said, "You cursed my father and bad luck befell him; but bless me, your humble servant, and I will carry your yoke." We don't know if Assyrian help arrived, but Lydia was freed from the Cimmerians.

Civil War with Shamash-shum-ukin

Growing Problems and Rebellion

Esarhaddon's plans suggested that Shamash-shum-ukin should rule all of Babylonia. But records only show that Shamash-shum-ukin controlled Babylon and its nearby areas. Governors of other Babylonian cities, like Nippur, Uruk, and Ur, saw Ashurbanipal as their king, not Shamash-shum-ukin.

At first, Shamash-shum-ukin seemed to like his brother. He called Ashurbanipal "my brother" in letters. But Ashurbanipal's constant involvement in Babylonian affairs made Shamash-shum-ukin unhappy. He also felt that Ashurbanipal often delayed help when it was needed. By the 650s, Shamash-shum-ukin's opinion of Ashurbanipal had worsened. A letter from a courtier named Zakir to Ashurbanipal described how people from the Sea Land openly criticized Ashurbanipal in front of Shamash-shum-ukin.

Shamash-shum-ukin wanted to be independent and rule Babylonia himself. So, he rebelled in 652 BCE. Legends say that their sister, Serua-eterat, tried to stop them from fighting. When the war started, she supposedly went into exile. The war between the brothers lasted three years. Shamash-shum-ukin knew he would get support in the south. Babylonians always disliked Assyrian control, and the rulers of Elam were always ready to fight Assyria. Ashurbanipal's records say Shamash-shum-ukin told Babylonians that "Ashurbanipal will cover with shame the name of the Babylonians." Soon after Shamash-shum-ukin rebelled, the rest of southern Mesopotamia also rose up against Ashurbanipal.

Ashurbanipal's records say Shamash-shum-ukin found many allies. These included the Chaldeans, Arameans, and other people of Babylonia. The Elamites also joined him. Shamash-shum-ukin's messengers offered gifts to the Elamites, and their king, Ummanigash, sent an army. For the first two years, battles were fought all over Babylonia. Both sides won some battles. The war became confusing, with minor players changing sides. One famous double agent was Nabu-bel-shumati, a governor who betrayed Ashurbanipal many times.

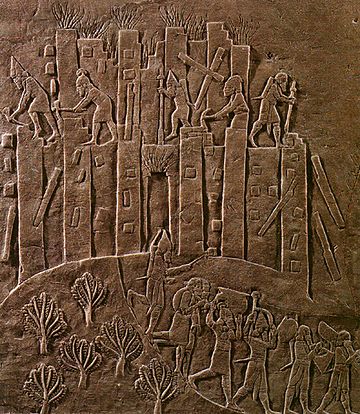

Shamash-shum-ukin's Defeat

Even with many allies, Shamash-shum-ukin could not stop Ashurbanipal. His forces were slowly defeated, his allies left him, and he lost his lands. By 650 BCE, things looked bad. Ashurbanipal's armies had surrounded Sippar, Borsippa, Kutha, and Babylon itself. During Ashurbanipal's siege of Babylon, the city suffered from a terrible famine. Ashurbanipal's account says some citizens were so hungry they ate their own children. After two years of starvation and disease, Babylon fell in 648 BCE. Ashurbanipal's army heavily looted the city. A great fire also spread through Babylon. Shamash-shum-ukin is believed to have taken his own life. Texts say he "met a cruel death" and the gods "consigned him to a fire."

After defeating Shamash-shum-ukin, Ashurbanipal appointed a new king for Babylon, Kandalanu. We don't know much about Kandalanu. His rule covered the same area as Shamash-shum-ukin's, except for Nippur. Ashurbanipal made Nippur a strong Assyrian fortress. Kandalanu probably had very limited power. Ashurbanipal held the real control.

This civil war was a difficult victory for Ashurbanipal because a member of the royal family died. The war also greatly weakened the Assyrian Empire. It used up a lot of money and resources. Historians believe this war marked the end of Assyria's greatest power. Ashurbanipal's harsh looting of Babylon, for the second time in 30 years, made people in southern Babylonia hate Assyria even more. This might have led to the rise of the Neo-Babylonian Empire and the fall of Assyria a few years after Ashurbanipal's death.

The Destruction of Elam

Elam's support for Shamash-shum-ukin ended when their army was defeated near Der. After this defeat, Tammaritu II took the throne in Elam from Ummanigash. Ummanigash fled to Assyria, and Ashurbanipal gave him a safe place to stay. Tammaritu II's rule was short. Even though he won some battles against the Assyrians, he was overthrown in another revolt in 649 BCE. The new king, Indabibi, ruled for a very short time. He was murdered after Ashurbanipal threatened to invade Elam again because of their help to Shamash-shum-ukin.

Humban-haltash III became king in Elam. The rebel governor Nabu-bel-shumati continued fighting Ashurbanipal from Elam. Humban-haltash wanted to hand over Nabu-bel-shumati, but Nabu-bel-shumati had too many supporters in Elam. Because Humban-haltash couldn't meet Ashurbanipal's demands, the Assyrians invaded Elam again in 647 BCE. The Elamite defenses collapsed, and Humban-haltash fled to the mountains. Tammaritu II briefly became king again. After the Assyrians looted the region of Khuzestan, they went home. Humban-haltash then came back and took the throne again.

The Assyrians returned to Elam in 646 BCE. Humban-haltash again fled. Ashurbanipal's forces chased him, destroying cities along the way. All major Elamite cities were crushed. Nearby kingdoms that used to pay tribute to Elam now paid tribute to Ashurbanipal. This included Parsua, possibly an early form of the empire that would be founded by the Achaemenids later. Parsua's king, Cyrus (possibly Cyrus I), had sided with Elam. He was forced to send his son Arukku as a hostage. Even countries that had never met Assyrians before, like a kingdom beyond Elam, started paying tribute.

On their way back, the Assyrian forces brutally looted Susa. Ashurbanipal's records describe this in great detail. They say the Assyrians destroyed royal tombs, looted temples, stole statues of Elamite gods, and sowed salt in the ground. The ancient Elamite capital was wiped out. Ashurbanipal continued destroying Elamite settlements on a massive scale. Thousands of Elamites who were not killed were taken away from their homes. Ashurbanipal's harsh actions against Elam are sometimes seen as an attempt to completely destroy their culture. The detailed records of his destruction suggest he wanted to shock the world and show that the Elamites were defeated forever.

Despite this brutal campaign, Elam continued to exist for some time. Ashurbanipal did not take over Elam. He left it to itself. Humban-haltash returned to rule and later sent Nabu-bel-shumati to Ashurbanipal, though the rebel died on the way. After Humban-haltash was captured and sent to Assyria, Assyrian records stop mentioning Elam. Elam never fully recovered from Ashurbanipal's attacks in 646 BCE. It was left open to attacks from other tribes and eventually disappeared from history.

Wars in Arabia

Assyrian control in the west was sometimes challenged by Arab tribes. These groups would raid Assyrian lands or disrupt trade. Ashurbanipal led two campaigns against Arab tribes. His own writings describe these wars in great detail.

Ashurbanipal's first war against the Arabs happened before the civil war with Shamash-shum-ukin. It was mainly against the Qedarites. Ashurbanipal's earliest account from 649 BCE says that Yauta, son of Hazael, king of the Qedarites, rebelled with another Arab king, Ammuladdin. They looted Assyrian lands in the west. The Assyrian army, with help from Kamas-halta of Moab, defeated them. Ammuladdin was captured, but Yauta escaped. Ashurbanipal made a loyal Arab leader named Abiyate the new king of the Qedarites. Later versions of this story also say Ashurbanipal defeated Adiya, an Arab queen. They also connect Yauta's rebellion to Shamash-shum-ukin's revolt, suggesting the Arab raids were caused by the civil war. In both accounts, the Qedarite lands were heavily looted.

Some Arab leaders joined Shamash-shum-ukin in the civil war. These included Abiyate, whom Ashurbanipal had made king, and his brother Aya-ammu. They sent soldiers to Babylonia. Because Ashurbanipal was focused on Elam, they were not punished right away. As the Elamite wars continued, several Arab rulers stopped paying tribute and began raiding Assyrian settlements. This disrupted trade. Ashurbanipal's generals then organized a major campaign to restore order.

Ashurbanipal's account of this second war mainly describes his army's movements through Syria. They were searching for Uiate (possibly Yauta, or a different person) and his Arab soldiers. The Assyrian army marched from Syria to Damascus and then to Hulhuliti. They captured Abiyate and defeated Uššo and Akko. The Assyrians faced many difficulties because the land was unfamiliar and hostile. The Nabayyate, who had helped Ashurbanipal before, were defeated in this second war. The last version of the Arabian story says these two campaigns were Ashurbanipal's ninth. It adds more details. In this version, Abiyate and Ammuladdin joined Shamash-shum-ukin. Ashurbanipal is also personally credited with the victories. This version also says Uiate was captured and paraded in Nineveh. It claims Uiate was tied to Ashurbanipal's chariot like a horse, and Aya-ammu was brutally killed.

The treasures brought back from the Arabian campaigns were supposedly so vast that they caused prices to rise in Assyria and famine in Arabia. While impressive, these campaigns are sometimes seen as a mistake. They took a lot of time and resources but failed to establish lasting Assyrian control over these lands.

Later Years and Successors

The end of Ashurbanipal's reign and the start of his son Ashur-etil-ilani's rule are unclear. We don't have many records after 649 BCE. After 639 BCE, only two inscriptions by Ashurbanipal are known. This lack of information might mean there was a serious political crisis. Ashurbanipal's later years seem to show a growing distance between the king and the traditional leaders of the empire. He gave important jobs to eunuchs, which might have upset the nobles. Some historians compare this period to the legend of Sardanapalus, the supposedly lazy last king of Assyria. Ashurbanipal himself knew that he had not made the empire last forever. In one of his last known writings, he expressed sadness about the state of his empire.

Besides internal problems, the Assyrian Empire's control over its distant regions weakened greatly by the end of Ashurbanipal's reign. Some areas gained independence. For example, Assyria no longer controlled the southern Levant. Egypt had become the main power there. Egypt regained its independence peacefully under Necho I's son, Psamtik I. Psamtik had been educated at the Assyrian court. He became king in 664 BCE as a loyal Assyrian ruler. But he slowly expanded his control over all of Egypt, uniting the country in 656 BCE. He became fully independent of Ashurbanipal. Psamtik remained an ally of Assyria. Later, during the fall of Assyria under Sinsharishkun (Ashur-etil-ilani's successor and another son of Ashurbanipal), both Psamtik and his son Necho II sent Egyptian armies to help the Assyrians.

Inscriptions by Ashur-etil-ilani suggest his father died a natural death. But they don't say when or how. Ashurbanipal's last known year as king is 631 BCE. If he had ruled until 627 BCE, as some older sources suggest, his sons' reigns would not make sense. It is generally agreed that Ashurbanipal died, stepped down, or was removed from power in 631 or 630 BCE. Most historians favor 631 BCE as the year of his death. Ashurbanipal was followed by his son Ashur-etil-ilani. Ashurbanipal seems to have followed his father's plan for succession. He gave Sinsharishkun the fortress-city of Nippur. Sinsharishkun was meant to take over Babylon after Kandalanu died.

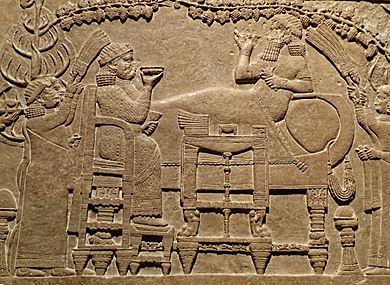

Family and Children

Ashurbanipal was married to his queen, Libbali-sharrat (Akkadian: Libbali-šarrat), when he became king. They might have married around the time he was named crown prince. Her name, which includes "queen," suggests it was not her birth name. She probably took it when she married Ashurbanipal. Libbali-sharrat is famous for appearing in the "Garden Party" relief from Ashurbanipal's palace. This relief shows her and Ashurbanipal eating together. It's special because it focuses on Libbali-sharrat, and it's the only known ancient Assyrian art showing someone other than the king hosting a royal event.

Ashurbanipal had at least three sons whose names we know:

- Ashur-etil-ilani (Akkadian: Aššur-etil-ilāni), who was king from 631–627 BCE.

- Sinsharishkun (Akkadian: Sîn-šar-iškun), who was king from 627–612 BCE.

- Ninurta-sharru-usur (Akkadian: Ninurta-šarru-uṣur), who did not play a political role.

Libbali-sharrat was likely the mother of Ashur-etil-ilani and Sinsharishkun. Ninurta-sharru-usur probably had less power because he was the son of a different wife. Libbali-sharrat might have lived after Ashurbanipal died in 631 BCE. A tablet from Ashur-etil-ilani's reign mentions the "mother of the king." Sinsharishkun's inscriptions say he was chosen for kingship "from among his equals" (his brothers). This suggests Ashurbanipal had more sons than the three we know by name. We also know Ashurbanipal had at least one daughter, as documents mention a "daughter of the king."

Ashurbanipal's family line might have continued after Assyria fell in 612–609 BCE. The mother of the last Neo-Babylonian king, Nabonidus, was named Adad-guppi. She was from Harran and had Assyrian family. She claimed Nabonidus was from Ashurbanipal's family. However, some historians disagree, saying there's no proof Nabonidus was related to Ashurbanipal's family.

Character

His Tough Rule

In Assyrian royal beliefs, the king was chosen by the god Ashur. The king was seen as having a duty to expand Assyria. Lands outside Assyria were thought to be wild and a threat to order. Expanding the empire was seen as a moral duty to bring civilization, not just to conquer. Fighting against Assyrian rule was seen as fighting against the gods, and it deserved punishment.

Ashurbanipal's army fought further away from Assyria than ever before. Although Ashurbanipal probably didn't fight in battles himself, he was known for being exceptionally tough. It's possible his strong actions were partly due to his religious beliefs. He rebuilt and expanded many temples. Many of his decisions were based on omens, which he was very interested in. He also made two of his younger brothers priests.

When looking at all Assyrian art showing tough actions, most of them are from Ashurbanipal's reign.

His Love for Culture

The Library of Ashurbanipal

Ashurbanipal saw himself as strong in both body and mind. His inscriptions often show him with weapons and a writing tool. They say he was different from earlier kings because he was very skilled in literature, writing, math, and learning. He was deeply interested in ancient Mesopotamian writings. He read complex texts in both Akkadian and Sumerian from a young age.

After he became king, Ashurbanipal used his empire's vast resources to create the world's first "universal" library in Nineveh. The Library of Ashurbanipal was by far the largest library in ancient Assyria. It was also the first library organized in a systematic way. It might have held over 100,000 texts. It was not surpassed in size until the Library of Alexandria was built centuries later. About 30,000 documents from the library survived the destruction of Nineveh in 612 BCE. They have been found among the city's ruins.

Ashurbanipal ordered scribes to go throughout the empire. They collected and copied all kinds of texts from temple libraries. Most of the texts were observations of events and omens. There were also texts about human and animal behavior, and the movements of stars. The library also had dictionaries for Sumerian, Akkadian, and other languages. It contained many religious texts, like rituals, fables, prayers, and spells. Many tablets from Babylonia were in the library, some given as gifts, others taken as war prizes. Ashurbanipal's library likely contained a complete picture of Mesopotamian knowledge up to his time. Ashurbanipal himself thought the library was the greatest achievement of his reign.

People in Mesopotamia remembered the library for a long time. Even in the first century AD, scribes in Babylonia still mentioned the lost library in their writings. Most of the traditional Mesopotamian stories we know today, like the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Enûma Eliš (the Babylonian creation story), survived because they were in Ashurbanipal's library. The library also had folk tales and scientific texts.

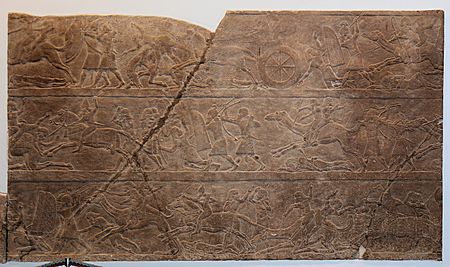

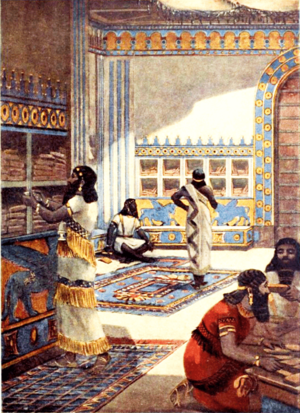

Artwork

Ashurbanipal supported the arts. He had many sculptures and reliefs made for his palaces in Nineveh. These artworks showed important events from his long reign. Ashurbanipal's art was new for Assyrian art history. It often had an "epic quality" that was different from the more rigid art of earlier kings. A common theme in his art, like the Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal, shows the king killing lions. This was a way to show his glory, power, and his ability to protect the Assyrian people.

New ideas appeared in art made during Ashurbanipal's time. The king's clothing changed depending on the scene. For example, informal events showed Ashurbanipal with a different, open crown. There are no known artworks showing Ashurbanipal sitting on a throne or holding court. This was common for earlier kings. This might mean the symbol of the throne was becoming less important in art and at court. Ashurbanipal's artwork is the only ancient Assyrian art that shows non-Assyrians as physically different from Assyrians. They are shown with different features, not just different clothes. This might have been influenced by Egyptian art. However, writings from Ashurbanipal's time don't suggest that foreigners were seen as biologically different. So, this might have just been an artistic choice.

Legacy

The Sardanapalus Legend

Stories about Ashurbanipal lived on in the Near East. He might be the "Asnappar" mentioned briefly in the Biblical Book of Ezra (4:10). Ashurbanipal and other ancient Assyrian figures appeared in folklore and stories for centuries.

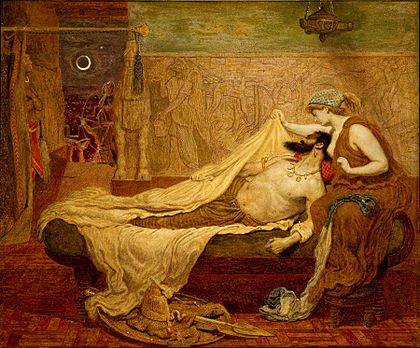

The most famous later story about Ashurbanipal was the Greek and Roman Sardanapalus legend. This legend described Sardanapalus as being "more like a woman than a man." He was seen as lazy and someone who disliked war. This view came from how ancient Greeks generally saw Mesopotamia. They often saw ancient Mesopotamian kings as weak and bad rulers. The first mention of Sardanapalus is from the 5th-century BCE Histories by Herodotus. It mentions the riches of Sardanapalus, king of Nineveh. Legends in Aramaic, based on the civil war between Ashurbanipal ("Sarbanabal") and Shamash-shum-ukin ("Sarmuge"), exist from the 3rd century BCE.

The longest ancient text about Sardanapalus is from the 1st-century BCE Bibliotheca historica by Diodorus Siculus. Siculus's description of Sardanapalus was influenced by Greek ideas about the East. The king was said to live among women, dress like them, and use a soft voice. In Siculus's story, Sardanapalus's governor of Media, Arbaces, saw him with women in the palace. Arbaces quickly rebelled and attacked Nineveh with a Babylonian priest. After failing to get his soldiers to defend the city, Sardanapalus locked himself in his palace with treasures and women. He then lit a huge fire, burning down the entire capital and ending the Assyrian Empire. It's clear that Siculus's Sardanapalus is based on Ashurbanipal, but also on Shamash-shum-ukin and Sinsharishkun.

The Greek stories about ancient Assyria changed how people viewed the empire for centuries. Since there was little real evidence of Assyria and Babylonia, writers and artists during the Renaissance and Enlightenment based their ideas on classical Greek and Roman writings. In the late 1600s, an Italian composer wrote an opera called Sardanapalo. It was a comedic tragedy where Sardanapalus was shown as a woman-like king. In the opera, Sardanapalus decides to burn his palace so that the Assyrian Empire would fall with a grand show. In 1821, Lord Byron wrote a play called Sardanapalus. It paired Sardanapalus with a Greek slave named Myrrah, who was loyal to him. In Byron's version, Myrrah lit the palace on fire after Sardanapalus's last words, "Adieu, Assyria! I loved thee well!". Many operas inspired by Byron had similar stories. It was common to show the fall of Nineveh and Assyria as a result of Assyria's supposed lack of good values, combined with its showiness.

Even after archaeologists found the true history of ancient Assyria in the 1800s, the Greek and Roman ideas about it remained strong. When archaeologist Austen Henry Layard found evidence of a big fire in the ruins of Nimrud in 1845, his colleagues thought it proved the Sardanapalus legend. Even after discoveries showed that the legendary Sardanapalus was very different from the real Ashurbanipal, the legend was not forgotten. Instead, plays and films about Sardanapalus began to mix the legend with historical facts. Many plays started to include Assyrian architectural details. Two films based on the Sardanapalus legend have been made in Italy. Both were influenced by Byron's play and focused on Sardanapalus's relationship with Myrrah. One film also included Ashurbanipal's conflict with Shamash-shum-ukin.

Modern Views

Discoveries and Opinions

The North Palace of Nineveh, built by Ashurbanipal, was found by archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam in December 1853. Rassam's excavations were marked by a rivalry with French archaeologist Victor Place. Despite agreements, Rassam found Ashurbanipal's palace at night. Excavations took place in the palace in 1853–1854. Rassam found the reliefs of the Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal. These were taken to the British Museum in England in March 1856. Because of disagreements and funding issues, studies of the finds from Ashurbanipal's palace were slow. The first detailed studies were not published until the 1930s and 1940s.

Ashurbanipal's reign was the last time Assyrian armies fought across the Middle East. He is often called the "last great king of Assyria." His reign is sometimes seen as the peak of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. However, many scholars think his father Esarhaddon's reign was the peak. Historians disagree about whether Ashurbanipal is to blame for the fall of the Assyrian Empire soon after his death. Some say the empire was already showing signs of trouble under Ashurbanipal. Others say its fall was due to outside pressures, not internal problems. Some believe the fall was due to Ashurbanipal's later "average heirs." However, there is no proof his heirs were bad rulers. Sinsharishkun, under whom the empire fell, was a skilled military leader. Some historians believe the seeds of Assyria's fall were sown during Ashurbanipal's reign, especially because of the distance between the king and the traditional elite, and his harsh treatment of Babylon.

Titles

See also

In Spanish: Asurbanipal para niños

In Spanish: Asurbanipal para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |