Art of Mesopotamia facts for kids

The art of Mesopotamia comes from a very old region, often called the "cradle of civilization." This land, between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, saw the birth of writing and many amazing cultures. From early hunter-gatherer groups to powerful empires like the Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians, art played a huge role in their lives.

Mesopotamian art was as grand and detailed as the art of Ancient Egypt. It was the most impressive art in western Eurasia for thousands of years, until the Persian Achaemenid Empire took over in the 6th century BC. Artists mostly worked with stone and clay, creating sculptures that lasted a very long time. While not much painting survived, we know it often featured geometric shapes and plants. Many sculptures were also painted with bright colors. Tiny but detailed Cylinder seals, used to sign documents, are also found in large numbers.

Mesopotamian artists created many types of art. These included small statues, detailed carvings called reliefs, and clay plaques for homes. They often showed gods, people praying, and animals. Animals might appear in rows, fighting, or with a human or god in a special design called the "Master of Animals" motif. Large stone slabs, known as stelae, were also made to celebrate victories or honor gods. The famous Assyrian Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III is a great example of these historical carvings.

Contents

- Discovering Ancient Mesopotamian Art

- Early Art: From Stone to Pottery

- The Art of Sumerian City-States

- Powerful Empires: Akkadian and Neo-Sumerian Art

- Later Mesopotamian Art: Babylon and Assyria

- What Made Mesopotamian Art Special?

- Amazing Buildings: Ziggurats and Palaces

- Sparkling Treasures: Mesopotamian Jewellery

- Where to See Mesopotamian Art Today

- Images for kids

Discovering Ancient Mesopotamian Art

Early Art: From Stone to Pottery

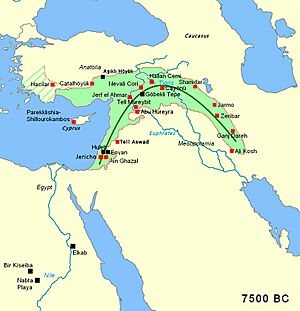

Long, long ago, people lived in the highlands of Mesopotamia. The earliest art appeared in northern Mesopotamia around 9,500–8,000 BC. These first artworks included simple carvings of people and animals. People also built huge stone structures called megaliths. The climate was different then, with forests and grasslands. After farming began, communities grew, often in hills that were easy to defend.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic Art (9000–7000 BC)

This period, before pottery was invented, saw some incredible creations. At Göbekli Tepe, people carved detailed animal reliefs and some human figures into stone around 9000 BC. The Urfa Man, found nearby, is a life-sized statue of a human, considered one of the oldest naturalistic sculptures ever found. Later, small human statues made of stone and clay appeared in places like Mureybet.

Around 8000 BC, people became very skilled at making beautiful stone containers. They used materials like alabaster and granite, shaping and polishing them with sand. These amazing vessels often highlighted the natural patterns in the stone.

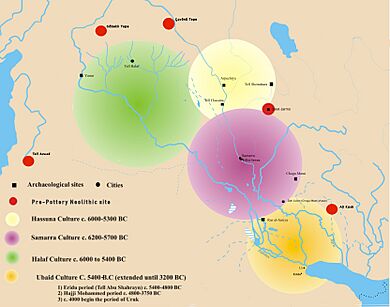

Decorated Pottery Cultures (7000–3800 BC)

The first pottery appeared in northern Mesopotamia around 7000 BC in sites like Tell Hassuna and Jarmo. This early pottery was handmade and simple. Artists also made clay figures of animals and pregnant women, possibly representing fertility goddesses.

Later, cultures like the Halaf culture (6000–5000 BC) created stunning pottery decorated with colorful geometric patterns. They also made painted clay figurines of women, perhaps goddesses. The Hassuna culture (6000–5000 BC) also used geometric shapes and some animal designs on their pottery. The Samarra culture (6000–4800 BC) made pottery with intricate designs, sometimes showing animals like fish and birds.

The Ubaid culture (6500–3800 BC) spread across much of Mesopotamia. Their pottery was also distinctive. During this time, stamp seals began to show animals in artistic ways. Towards the end of the Ubaid period, around 4000 BC, we see the first images of the "Master of Animals" motif, showing a hero controlling wild beasts.

The Art of Sumerian City-States

The Sumerian people, who spoke a unique language, developed amazing art and invented writing over about 2,000 years.

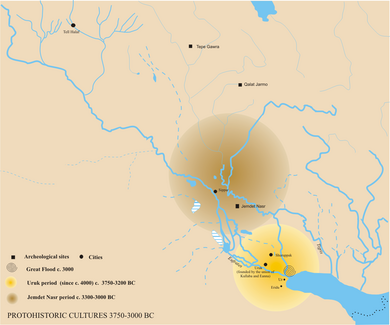

Uruk Period: Early Cities and Writing (4000–3100 BC)

The Uruk period, named after the city of Uruk, was a time of big changes. Cities grew, and Sumerian civilization began. This was a "great creative age" for Mesopotamian art. In northern cities like Tell Brak, people made "eye idols"—small statues with huge eyes, likely offerings to gods. Temples were decorated with colorful cone mosaics made of clay.

From southern cities, famous artworks include the Warka Vase and the Mask of Warka. The Warka Vase shows detailed scenes of people and animals. The Mask of Warka is a realistic stone head, probably of a goddess, meant to be part of a larger wooden statue with added colors and jewels. Cylinder seals from this time were very detailed, often showing animals that represented gods.

Early Dynastic Period: Royal Tombs and Worshippers (2900–2350 BC)

Art in the Early Dynastic Period focused on people praying, priests, and scenes of daily life, war, and court events. Artists started using copper for sculptures, though many were later melted down. A huge copper carving, the Tell al-'Ubaid Copper Lintel, shows how skilled they were.

Many treasures were found in the Royal Cemetery at Ur (around 2650 BC). These include the famous Ram in a Thicket statues, a Copper Bull, and bull heads on the Lyres of Ur. The Standard of Ur, a decorated box, shows beautiful scenes made with shells and colorful stones.

A group of 12 temple statues, called the Tell Asmar Hoard, shows gods, priests, and worshippers. They all have very large, inlaid eyes, with the tallest god figure having especially huge eyes that look very powerful.

Powerful Empires: Akkadian and Neo-Sumerian Art

Akkadian Empire: Kings and Realism (2271–2154 BC)

The Akkadian Empire was the first to rule all of Mesopotamia and more. Akkadian art focused a lot on the kings. It showed a new level of realism, making figures look more lifelike.

King Naram-Sin's famous Victory Stele shows him as a god-king, climbing a mountain over his defeated enemies. This tall, pink sandstone carving uses diagonal lines to tell the story, which was a new idea at the time. Another amazing piece is a life-sized bronze head of a bearded ruler, possibly Sargon of Akkad or Naram-Sin. It shows incredible detail in the hair and beard and is one of the earliest examples of hollow metal casting.

Neo-Sumerian Period: Gudea's Statues (2112–2004 BC)

After the Akkadian Empire, a new Sumerian period brought back local rulers. Gudea, a ruler of Lagash, was a big supporter of art. Many beautiful statues of Gudea, mostly small and made of hard diorite stone, have been found. These statues show a calm and confident style. The art of the Third Dynasty of Ur also reached new levels of realism and craftsmanship.

Later Mesopotamian Art: Babylon and Assyria

Old Babylonian Period: Hammurabi's Time (1830–1531 BC)

During the First Babylonian Dynasty, King Hammurabi (1792–1750 BC) made Babylon a powerful city. He is famous for his law code. Art from this time often kept older Sumerian styles. The Burney Relief is a unique and large clay plaque showing a winged goddess with bird feet, surrounded by owls and lions. It might have been used in homes or small shrines.

A large palace painting called the Investiture of Zimri-Lim, found in Mari, is a rare surviving example of Mesopotamian wall-painting.

Assyrian Empire: Grand Palaces and Reliefs (1500–612 BC)

The Assyrian Empire was huge and wealthy, and its art was very grand. From around 879 BC, Assyrians created massive, detailed stone reliefs for their palaces. These carvings, originally painted, showed royal events like hunting and battles. Animals, especially horses and lions, are shown with amazing detail and energy. Famous examples include the Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal and the Lachish reliefs, both found in Nineveh.

Assyrians also made colossal guardian figures called lamassu. These had human heads and the bodies of lions or bulls, often with wings. They guarded royal gateways and were carved in high relief, looking like full statues from the front. Assyrian art also influenced ancient Greek art, especially with its winged creatures.

Neo-Babylonian Empire: The Ishtar Gate (626–539 BC)

The Neo-Babylonian Empire is famous for the magnificent Ishtar Gate, built around 575 BC by King Nebuchadnezzar II. This gate was the main entrance to Babylon. Its walls are decorated with rows of large, colorful animals—lions, dragons, and bulls—made from glazed bricks. These bricks kept their bright colors over thousands of years. The gate was part of a grand processional way leading into the city.

Neo-Babylonian artists continued many traditional art forms, proudly showing off their ancient heritage. After the Persian Empire conquered Mesopotamia, Mesopotamian art still influenced the new styles that emerged.

What Made Mesopotamian Art Special?

Mesopotamian art wasn't just about copying reality. Artists wanted to create images that felt like the real thing, almost like a substitute. These artworks were seen as a part of actual reality, holding special power and meaning. Sculptures, often small, were the main type of art that survived. Many Sumerian and Akkadian statues show figures in prayer.

Amazing Buildings: Ziggurats and Palaces

Ancient Mesopotamia is famous for its buildings made of mud brick, especially the ziggurats. A ziggurat was a huge stepped pyramid with stairs leading to a temple at the top. These tall structures helped the temples stand out in the flat river valleys, bringing them "closer to the heavens." The Ziggurat of Ur, for example, was originally about 12 meters tall with three stories.

Assyrian palaces were also grand, with large public courtyards and many rooms. They were built to show the king's power and glory.

Sparkling Treasures: Mesopotamian Jewellery

Mesopotamian jewellery often featured natural shapes like leaves and grapes, or geometric patterns. Sumerian and Akkadian jewellery used gold and silver, decorated with colorful semiprecious stones like agate, carnelian, jasper, and lapis lazuli.

Later, Mesopotamian jewellers used advanced techniques like cloisonné (creating compartments for gems), engraving, and filigree (delicate wirework). Both men and women, and even children, wore a wide variety of necklaces, bracelets, anklets, and pins.

Where to See Mesopotamian Art Today

You can see amazing collections of Mesopotamian art in museums around the world. Some of the most important include the Louvre Museum in Paris, the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin, the British Museum in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, and the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad. The reconstructed Ishtar Gate is a highlight at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.

Other museums with great collections include the Oriental Institute of Chicago, İstanbul Archaeology Museums, and the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Images for kids

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |