Early Dynastic Period (Mesopotamia) facts for kids

|

|

| Geographical range | Mesopotamia |

|---|---|

| Period | Bronze Age |

| Dates | fl. c. 2900 – c. 2350 BC (middle) |

| Type site | Tell Khafajah, Tell Agrab, Tell Asmar |

| Major sites | Tell Abu Shahrain, Tell al-Madain, Tell as-Senkereh, Tell Abu Habbah, Tell Fara, Tell Uheimir, Tell al-Muqayyar, Tell Bismaya, Tell Hariri |

| Preceded by | Jemdet Nasr Period |

| Followed by | Akkadian Period |

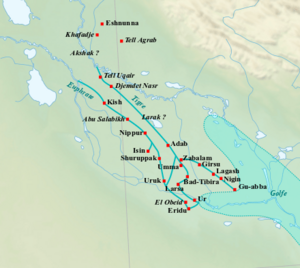

The Early Dynastic period (often called ED period) was a time in Mesopotamia (which is modern-day Iraq) from about 2900 to 2350 BC. It came after the Uruk and Jemdet Nasr periods. During this time, people started to develop writing and build the very first cities and states. The ED period was known for having many small states called city-states. These were like tiny countries, each with its own city as the capital. Over time, these city-states grew stronger. Eventually, much of Mesopotamia was united under one ruler, Sargon of Akkad, who started the Akkadian Empire. Even though these city-states were separate, they shared many similar ways of life and culture. Powerful Sumerian cities like Uruk, Ur, Lagash, Umma, and Nippur were in the southern part of Mesopotamia. To the north and west, there were other important cities like Kish, Mari, Nagar, and Ebla.

For a long time, experts mostly studied the central and southern parts of Mesopotamia. Many ancient sites there, like Girsu, Eshnunna, Khafajah, and Ur, have been dug up since the 1800s. These digs found many important items, including cuneiform texts (early writing). This meant we knew more about these areas. But then, new discoveries from Ebla in Syria changed things. They showed us more about nearby places like Upper Mesopotamia, western Syria, and southwestern Iran. These new findings proved that all these areas shared many cultural ideas. They also traded goods and ideas across the entire ancient Near East.

Contents

How We Study the Early Dynastic Period

Who Named This Period?

The name "Early Dynastic" for Mesopotamia was created by a Dutch archaeologist named Henri Frankfort. He borrowed the idea from a similar period in ancient Egypt. Frankfort developed this way of dividing time in the 1930s. He was working for the University of Chicago Oriental Institute. His team was digging at sites like Tell Khafajah, Tell Agrab, and Tell Asmar in the Diyala River area of Iraq.

Dividing the Early Dynastic Period

The Early Dynastic period was first split into three parts: ED I, ED II, and ED III. This was mainly based on how a temple in Tell Asmar was rebuilt many times. Each time, the temple's design changed. For a long time, archaeologists tried to use this ED I–III system everywhere in Iraq and Syria. But later, they found that this system didn't work for all regions.

For example, research in Syria showed that things developed very differently there. So, the old way of dating periods from southern Mesopotamia didn't fit. In the 1990s and 2000s, experts created a new timeline for Upper Mesopotamia. It's called the Early Jezirah (EJ) 0–V chronology. Now, the ED I–III timeline is mostly used only for southern Mesopotamia. Some even question if ED II should be used at all.

What Was the Early Dynastic Period Like?

When Did It Happen?

The Early Dynastic period came after the Jemdet Nasr period. It was followed by the Akkadian period. That's when a large part of Mesopotamia was ruled by one person for the first time. The ED period is generally dated from about 2900 to 2350 BC. This is based on the most accepted timeline, called the middle chronology.

The ED period is divided into ED I, ED II, ED IIIa, and ED IIIb. These periods happened at roughly the same time as EJ I–III in Upper Mesopotamia. The exact dates for these sub-periods can vary a bit among experts. Some even combine ED I and ED II into just "Early ED" and "Late ED."

Why the Name "Early Dynastic"?

Many historical periods are named after the main rulers or empires of that time. But the ED period is different. It's an archaeological name. This means it's based on changes seen in ancient objects and sites, like pottery. We don't know much about the political history of the ED period for most of its time. Experts often disagree on how to piece together the political events.

| Period | Middle Chronology All dates BC |

Short Chronology All dates BC |

|---|---|---|

| ED I | 2900–2750/2700 | 2800–2600 |

| ED II | 2750/2700–2600 | 2600–2500 |

| ED IIIa | 2600–2500/2450 | 2500–2375 |

| ED IIIb | 2500/2450–2350 | 2375–2230 |

ED I: The Early Years

The ED I period (2900–2750/2700 BC) is not as well understood as later times. In southern Mesopotamia, it shared features with the end of the Uruk and Jemdet Nasr periods. ED I is known for a type of pottery called Scarlet Ware. This pottery was found along the Diyala River. It was also a time for the Ninevite V culture in Upper Mesopotamia and the Proto-Elamite culture in southwestern Iran.

ED II: Legends and Art

New art styles appeared in southern Mesopotamia during ED II (2750/2700–2600 BC). These styles influenced nearby regions. Later Mesopotamian stories say that legendary kings like Lugalbanda, Enmerkar, Gilgamesh, and Aga ruled during this time. However, archaeologists haven't found much evidence for this period in southern Mesopotamia. This has led some researchers to skip ED II entirely.

ED III: Growth and Conflict

The ED III period (2600–2350 BC) saw more writing and bigger differences between rich and poor. Larger political groups formed in Upper Mesopotamia and southwestern Iran. ED III is usually split into ED IIIa (2600–2500/2450 BC) and ED IIIb (2500/2450–2350 BC). Famous finds like the Royal Cemetery at Ur and texts from Fara and Abu Salabikh are from ED IIIa. ED IIIb is especially known from texts found in Girsu (part of Lagash) in Iraq and Ebla in Syria.

The end of the ED period is marked by political changes, not archaeological ones. Sargon of Akkad and his successors conquered many areas. This changed the balance of power across Iraq, Syria, and Iran. It's hard to tell the difference between ED III and the Akkadian period just by looking at pottery or buildings.

History of the Early Dynastic Period

What Do We Know from Ancient Texts?

We can't fully reconstruct the political history of the Early Dynastic period from the texts we have. Royal writings mostly talk about rulers' good deeds, like building temples. They don't give much detail about wars or diplomacy.

For ED I and ED II, there are no texts about wars or treaties. Only for the end of ED III do we have texts that help us understand political events. The biggest collections of clay tablets come from Lagash and Ebla. Smaller groups of tablets were found at Ur, Tell Beydar, Tell Fara, Abu Salabikh, and Mari. These texts show that Mesopotamian states were always in touch. They formed alliances and sometimes one state would become more powerful than others. This hinted at the later rise of the Akkadian Empire.

The famous Sumerian King List was written much later, around 2000 BC. It lists royal families from different Sumerian cities. It says each family ruled the region for a time before being replaced. Later kings used this list to prove their right to rule. Some parts of the list can be checked with other texts, but much of it is probably made-up. So, it's not a very reliable history book for the Early Dynastic period.

Diplomacy: Working Together

The Sumerian city-states might have shared a common culture, even though they were politically separate. Ancient texts and cylinder seals suggest there was a group or alliance of Sumerian cities. For example, clay tablets from Ur have seal marks with symbols of other cities. These marks have also been found at Jemdet Nasr, Uruk, and Susa. Some even show the same list of cities. This might mean that certain cities were responsible for giving offerings to major Sumerian temples.

Texts from Shuruppak (ED IIIa) also seem to confirm this alliance. Cities like Umma, Lagash, Uruk, Nippur, and Adab were part of it. Kish might have been the leader, and Shuruppak the administrative center. This alliance likely focused on trade and military help. Each city would send soldiers to the group. The importance of Kish is shown by its ruler, Mesilim (around 2500 BC). He helped settle a fight between Lagash and Umma. Later, rulers from other cities would use the title "King of Kish" to show their power.

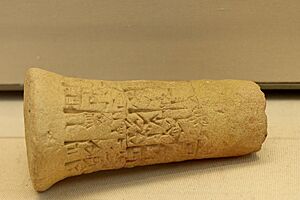

Texts from this time also show the first signs of a wide diplomatic network. For example, a peace treaty between Entemena of Lagash and Lugal-kinishe-dudu of Uruk is recorded on a clay nail. This is the oldest known agreement of its kind. Tablets from Girsu record gifts exchanged between royal families and foreign states. For instance, Baranamtarra, the wife of King Lugalanda of Lagash, exchanged gifts with rulers from Adab and even Dilmun.

War: Conflicts and Conquerors

The first recorded war in history happened in Mesopotamia around 2700 BC. It was during the ED period, between the forces of Sumer and Elam. The Sumerians, led by Enmebaragesi, the King of Kish, defeated the Elamites. The record says they "carried away as spoils the weapons of Elam."

We only have reliable information about wars for the later part of the ED period (ED IIIb). These texts mainly come from Lagash. They describe ongoing fights with Umma over control of farmland. Kings of Lagash and Umma are not on the Sumerian King List. This suggests that even though they were powerful then, they were later forgotten.

Royal writings from Lagash also mention wars against other city-states in southern Mesopotamia. They even fought kingdoms further away, like Mari, Subartu, and Elam. These conflicts show that even then, stronger states were starting to control larger areas. For example, King Eannatum of Lagash defeated Mari and Elam around 2450 BC. Enshakushanna of Uruk captured Kish and its king around 2350 BC. Lugal-zage-si, king of Uruk and Umma, took control of most of southern Mesopotamia around 2358 BC. This time of warring city-states ended when the Akkadian Empire rose under Sargon of Akkad in 2334 BC.

Neighboring Areas: Beyond Mesopotamia

We know a lot about the political history of Upper Mesopotamia and Syria from the royal texts found at Ebla. Ebla, Mari, and Nagar were the most powerful states there. The earliest texts show that Ebla used to pay tribute to Mari. But Ebla won a military victory and stopped paying. Cities like Emar and Abarsal were under Ebla's control. Ebla and Nagar exchanged gifts, and a royal marriage happened between their ruling families. These texts also include letters from faraway kingdoms like Kish. In many ways, the diplomacy of this time was similar to later periods.

Recent Discoveries

In March 2020, archaeologists found a 5,000-year-old religious area at Girsu. It was full of over 300 broken ceremonial cups, bowls, jars, and animal bones. These were used in rituals for the god Ningirsu. One special find was a duck-shaped bronze statue with bark eyes. It is thought to be dedicated to the goddess Nanshe.

Early Dynastic Kingdoms and Rulers

The Early Dynastic period (around 2900–2350 BCE) came after the Uruk period and the Jemdet Nasr period. It was followed by the rise of the Akkadian Empire.

| Dynasties | Dates | Main rulers | Cities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Dynasty of Kish | c. 2900 – c. 2500 BCE | Etana, Enmebaragesi | |

| 1st Dynasty of Uruk | c. 2900 – c. 2500 BCE | Enmerkar, Lugalbanda, Dumuzid the Fisherman, Gilgamesh | |

| 1st Dynasty of Ur | c. 2700 – c. 2300 BCE | Meskalamdug, Mesannepada, Puabi | |

| 2nd Dynasty of Uruk | c. 2500 – c. 2350 BCE | Enshakushanna | |

| 1st Dynasty of Lagash | c. 2500 – c. 2350 BCE | Ur-Nanshe, Eannatum, En-anna-tum I, Entemena, Urukagina | |

| Dynasty of Adab | c. 2350 BCE | Lugal-Anne-Mundu | |

| 3rd Dynasty of Kish | c. 2400 – c. 2350 BCE | Kubaba | |

| 3rd Dynasty of Uruk | c. 2350 – c. 2300 BCE | Lugal-zage-si |

Life in the Early Dynastic Period

Lower Mesopotamia: Land of Sumerians

The Uruk period before this saw the first cities, early governments, and writing. These practices continued and grew during the Early Dynastic period.

We can start to understand the different groups of people in Lower Mesopotamia during the ED period. This is because texts from this time had enough sound-based signs to show different languages. They also had personal names that could be linked to different groups. The texts suggest that southern Mesopotamia was mostly controlled by Sumer and its people, who spoke Sumerian. This was a unique language, not related to others.

Texts also show that Semitic-speaking people lived in the northern parts of Lower Mesopotamia. Their names and words were from an early form of the Akkadian language. However, some experts prefer to call this the "Kish civilization" after the powerful city of Kish. The ways of life and government were different in these two regions. But Sumerian influence was very strong during the Early Dynastic period.

Farming in Lower Mesopotamia relied on lots of irrigation. Farmers grew barley and date palms, along with other garden crops. They also raised sheep and goats. This farming system was probably the most productive in the ancient Near East. It allowed many people to live in cities. Some believe that in certain areas of Sumer, three-quarters of the population lived in cities during ED III.

The main political system was the city-state. A large city controlled the farms and smaller towns around it. These city-states shared borders with other similar city-states. The most important centers were Uruk, Ur, Lagash, Adab, and Umma-Gisha. Texts from this time show that neighboring kingdoms often fought, especially Umma and Lagash.

The situation might have been different further north, where Semitic people seemed to be in charge. In this area, Kish might have been the center of a large state. It competed with other powerful places like Mari and Akshak.

The Diyala River valley is another well-known region from the ED period. This area was home to Scarlet Ware pottery. This pottery had painted geometric designs and figures of people and animals. In the Jebel Hamrin, fortresses like Tell Gubba and Tell Maddhur were built. Some think these protected the main trade route from Mesopotamia to Iran. The main Early Dynastic sites here are Tell Asmar and Khafajah. We don't know their political structure, but they were influenced by the larger cities in the lowlands.

Neighboring Regions: Beyond the River Valleys

Upper Mesopotamia and Central Syria

At the start of the third millennium BC, the Ninevite V culture thrived in Upper Mesopotamia and the Middle Euphrates River region. It spread from Yorghan Tepe in the east to the Khabur Triangle in the west. Ninevite V was from the same time as ED I. It was an important step in building more cities in the region. This period seemed to have less central control. There were no huge buildings or complex government systems like before.

After 2700 BC, and especially after 2500 BC, the main cities grew much larger. They were surrounded by towns and villages that they controlled. This shows that the area had many different political groups. Many sites in Upper Mesopotamia, like Tell Chuera and Tell Beydar, had a similar shape. They had a main mound (tell) surrounded by a circular lower town. German archaeologist Max von Oppenheim called them Kranzhügel, or "cup-and-saucer-hills." Important sites from this period include Tell Brak (Nagar), Tell Mozan, Tell Leilan, and Chagar Bazar in the Jezirah, and Mari on the middle Euphrates.

Cities also grew in western Syria, especially in the second half of the third millennium BC. Sites like Tell Banat, Tell Hadidi, Umm el-Marra, Qatna, Ebla, and Al-Rawda developed early forms of government. This is clear from the written records of Ebla. Large buildings like palaces, temples, and grand tombs appeared. There is also proof of rich and powerful local leaders.

The cities of Mari and Ebla are very important in the history of this region. According to the archaeologist who dug up Mari, this circular city on the middle Euphrates was built from scratch during the Early Dynastic I period. Mari was one of the main cities in the Middle East at this time. It fought many wars against Ebla in the 24th century BC. The texts from Ebla, the capital of a strong kingdom during ED IIIb, showed that writing and government were well-developed there. This was a surprise to experts before its discovery. However, few buildings from this period have been dug up at Ebla itself.

The kingdoms in these areas were much larger than those in southern Mesopotamia. However, fewer people lived there per square mile. Farming and raising animals were less intense than in the south. Towards the west, farming was more like the Mediterranean region. Growing olives and grapes was very important in Ebla. Sumerian culture influenced Mari and Ebla. These regions, with their Semitic populations, shared traits with the Kish civilization. But they also kept their own unique cultural features.

Iranian Plateau

In southwestern Iran, the first half of the Early Dynastic period was the Proto-Elamite period. This time was known for its unique art, a script that still hasn't been figured out, and advanced metalwork in the Lorestan region. This culture disappeared around the middle of the third millennium BC. It was replaced by a less settled way of life. We don't have many written records or archaeological digs from this period. So, we don't know much about the government or society of Proto-Elamite Iran. Mesopotamian texts show that Sumerian kings dealt with political groups in this area. For example, legends about the kings of Uruk mention conflicts with Aratta. As of 2017, Aratta hasn't been found, but it's thought to be somewhere in southwestern Iran.

In the middle of the third millennium BC, Elam became a powerful state. It was in the area of southern Lorestan and northern Khuzestan. Susa (level IV) was a key city in Elam. It was an important link between southwestern Iran and southern Mesopotamia. Hamazi was in the Zagros Mountains, possibly near Halabja.

This is also where the Jiroft culture appeared in the third millennium BC. We know about it from digs and stolen artifacts. Areas further north and east were important for international trade. They had tin (central Iran and the Hindu Kush) and lapis lazuli (Turkmenistan and northern Afghanistan). Settlements like Tepe Sialk, Tureng Tepe, Tepe Hissar, Namazga-Tepe, Altyndepe, Shahr-e Sukhteh, and Mundigak were local trade and production centers. But they don't seem to have been capitals of larger states.

Persian Gulf

More trade by sea in the Persian Gulf led to increased contact between southern Mesopotamia and other regions. Starting in the period before, the area of modern-day Oman (called Magan in ancient texts) developed oasis settlements. These relied on irrigation from natural springs. Magan was important in the trade network because of its copper mines. These mines were in the mountains, especially near Hili. Copper workshops and large tombs there show how wealthy the area was.

Further west was an area called Dilmun. In later times, this was modern-day Bahrain. However, even though Dilmun is mentioned in ED texts, no sites from this period have been found there. This might mean that Dilmun referred to the coastal areas that were used for sea trade.

Indus Valley: Distant Connections

Sea trade in the Gulf reached as far east as the Indian subcontinent. This is where the Indus Valley civilisation flourished. This trade grew stronger during the third millennium BC. It reached its peak during the Akkadian and Ur III periods.

Items found in the royal tombs of the First Dynasty of Ur show that foreign trade was very active. Many materials came from faraway lands. For example, Carnelian likely came from the Indus region or Iran. Lapis Lazuli came from Afghanistan. Silver came from Turkey. Copper came from Oman. Gold came from places like Egypt, Nubia, Turkey, or Iran. Carnelian beads with white designs, probably from the Indus Valley, were found in Ur tombs dating to 2600–2450 BC. This shows early Indus-Mesopotamia relations. These materials were used to make beautiful ornaments and ceremonial objects in Ur's workshops.

The First Dynasty of Ur was incredibly wealthy. This is clear from the richness of its tombs. Ur was probably the main port for trade with India (called Meluhha by Sumerians). This gave Ur a key position to import and trade large amounts of gold, carnelian, and lapis lazuli. In comparison, the tombs of the kings of Kish were much less grand. Tall Sumerian ships might have traveled all the way to Meluhha for trade.

Government and Economy

How Were Cities Ruled?

Each city had a main temple dedicated to its special god. A city was ruled by a "lugal" (king) or an "ensi" (priest-ruler), or sometimes both. People believed that the city's god chose the rulers. Rule could even move from one city to another. The priests of Nippur often had great influence over the Sumerian cities. Important cities included Eridu, Bad-tibira, Larsa, Sippar, Shuruppak, Kish, Uruk, Ur, Adab, and Akshak. Other important cities outside Mesopotamia were Hamazi, Awan (in Iran), and Mari (in Syria).

Some experts, like Thorkild Jacobsen, thought Sumerian cities had a "primitive democracy." This meant free citizens had a say in government. Kings like Gilgamesh of Uruk didn't have total power. They worked with councils of elders and younger men. Kings would ask these councils for advice on big decisions, like going to war. However, it's hard to tell if this was a true democracy or just a small group of powerful people.

The word "Lugal" (Sumerian for "great man") was one title for a Sumerian city-state ruler. The others were "EN" and "ensi." "Lugal" became the general word for "king." In Sumerian, "lugal" could mean an "owner" or the "head" of a family. The cuneiform sign for "lugal" was used to show that the next word was a king's name.

The exact meaning of "lugal" during the ED period is not fully clear. A city-state ruler was usually called "ensi." But a ruler of a group of states might be called "lugal." A lugal might have been a strong young man from a rich family.

Jacobsen suggested that a "lugal" was a chosen war leader, while an "EN" was a chosen governor for internal matters. A lugal's jobs might include leading the army, settling border fights, and performing religious duties. When a lugal died, his oldest son usually took over. Early rulers with the title "lugal" include Enmebaragesi and Mesilim of Kish, and Meskalamdug and Mesannepada of Ur.

"Ensi" (Sumerian for "Lord of the Plowland") was a title for a city's ruler or prince. People believed the ensi was a direct representative of the city's god. At first, "ensi" might have been used mainly for rulers of Lagash and Umma. In Lagash, "lugal" sometimes referred to the city's god, Ningirsu. Later, an "ensi" was usually under a "lugal."

"EN" (Sumerian for "lord" or "priest") referred to a high priest or priestess. It might also have been part of the title for the ruler of Uruk. "Ensi," "EN," and "Lugal" might have been local names for the rulers of Lagash, Uruk, and Ur, respectively.

Temples: Centers of Faith

The cities of Eridu and Uruk, two of the earliest, built large temple complexes from mud-brick. What started as small shrines grew into the biggest buildings in their cities during the ED period. Each temple was dedicated to its own god. Sumer was divided into about thirteen independent cities. These were separated by canals and boundary markers.

Population: How Many People Lived There?

Uruk, one of Sumer's largest cities, might have had 50,000 to 80,000 people at its busiest. Considering other cities and the large farming population, Sumer's total population could have been between 800,000 and 1,500,000 people. At this time, the world's population was estimated to be about 27,000,000.

Law: Rules for Society

Code of Urukagina

The ruler Urukagina of Lagash is famous for his efforts to fight corruption. His "Code of Urukagina" is sometimes called the earliest known legal code in history. It's also seen as the first recorded government reform, aiming for more freedom and equality. We haven't found the actual text of the Code of Urukagina. But we know much of its content from other writings. Urukagina made widows and orphans free from taxes. He made the city pay for funerals. He also said that rich people had to use silver when buying from the poor. If a poor person didn't want to sell, a powerful person couldn't force them. The Code of Urukagina limited the power of priests and large landowners. It also set rules against high interest rates, heavy controls, hunger, theft, murder, and taking people's property. Urukagina said: "The widow and the orphan were no longer at the mercy of the powerful man."

Even with these attempts to control the powerful, royal women might have had more influence during Urukagina's rule. Urukagina greatly expanded the royal "Household of Women." He gave it vast lands taken from the priests. His wife, Shasha (or Shagshag), supervised it. During his second year, his wife led the grand funeral for the previous queen, Baranamtarra, who was important in her own right.

Reform Document: Examples of Laws

Here are some examples from the "Reform Document":

- "From the border of Ningirsu to the sea, no person shall serve as officers."

- "For a body brought to the grave, his beer shall be 3 jugs and his bread 80 loaves. 1 bed and 1 lead goat shall the undertaker take away, and 3 ban of barley shall the person(s) take away."

- "When a person has been brought to the reeds of Enki, his beer will be 4 jugs, and his bread 420 loaves. 1 barig of barley shall the undertaker take away, and 3 ban of barley shall the persons of... take away. 1 woman’s headband, and 1 sila of princely fragrance shall the eresh-dingir priestess take away. 420 loaves of bread that have sat are the bread duty, 40 loaves of hot bread are for eating, and 10 loaves of hot bread are the bread of the table. 5 loaves of bread are for the persons of the levy, 2 mud vessels and 1 sadug vessel of beer are for the lamentation singers of Girsu. 490 loaves of bread, 2 mud vessels and 1 sadug vessel of beer are for the lamentation singers of Lagash. 406 of bread, 2 mud vessels, and 1 sadug vessel of beer are for the other lamentation singers. 250 loaves of bread and 1 mud vessel of beer are for the old wailing women. 180 loaves of bread and one mud vessel of beer are for the men of Nigin."

- "The blind one who stands in..., his bread for eating is 1 loaf, 5 loaves of bread are his at midnight, 1 loaf is his bread at midday, and 6 loaves are his bread in the evening."

- "60 loaves of bread, 1 mud vessel of beer, and 3 ban of barley are for the person who is to perform as the sagbur priest."

Trade: Connecting the World

Goods imported to Ur came from across the Near East and the Old World. Items like obsidian from Turkey, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, beads from Bahrain, and seals with Indus Valley script from India have been found in Ur. Metals were also imported. Sumerian stonemasons and jewelers used gold, silver, lapis lazuli, chlorite, ivory, iron, and carnelian. Even resin from Mozambique was found in the tomb of Queen Puabi at Ur.

The trade connections of Ur are clear from the imported items found. In the ED III period, objects from far-off places were common. These included gold, silver, lapis lazuli, and carnelian. These materials were not found in Mesopotamia itself.

Gold items were found in graves at the Royal Cemetery of Ur. They were also in royal treasuries and temples. This shows they were used for important and religious purposes. Gold items included personal ornaments, weapons, tools, seals, bowls, goblets, and sculptures.

Silver was found as belts, vessels, hair ornaments, pins, weapons, and sculptures. We have very few clues about where the silver came from.

Lapis lazuli was used in jewelry, plaques, gaming boards, lyres, and even parts of larger sculptures like the Ram in a Thicket. Larger objects included cups, dagger handles, and whetstones. Lapis lazuli showed high status.

Chlorite stone objects from the ED period are common. They include disc beads, ornaments, and stone vases. These vases were usually small, under 25 cm tall. They often had human and animal designs with colorful stone inlays. They might have held valuable oils.

Culture and Art

Sculpting: Art in Stone

Early Dynastic stone sculptures were mostly found in temples. They fall into two main types: three-dimensional prayer statues and carved stone slabs called bas-reliefs. The Tell Asmar Hoard is a famous example of ED sculpture. It was found in a temple and includes standing figures with hands folded in prayer. Some hold a cup for a ritual drink. Other statues show seated figures in similar prayer poses. Male figures wear simple or fringed dresses. These statues usually represent important people or rulers. They were placed in temples as offerings to pray for the person who paid for them. The Sumerian style greatly influenced nearby regions. Similar statues have been found in Upper Mesopotamia, including Assur, Tell Chuera, and Mari. However, some statues were more unique and less like Sumerian art.

-

Statue of a male figure, found at Tell Asmar

-

Statue of Ebih-Il, found at Mari (ED IIIb)

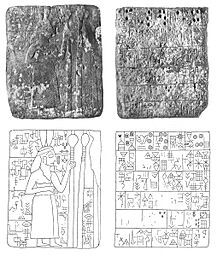

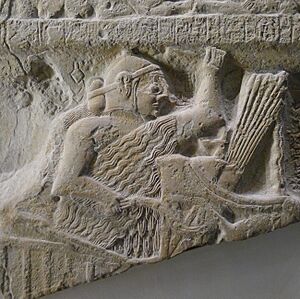

Bas-reliefs made from perforated stone slabs are another key type of ED sculpture. They were also offerings, but their exact use is unknown. Examples include the relief of King Ur-Nanshe of Lagash and his family, found at Girsu. Another is of Dudu, a priest of Ningirsu. This one shows mythical creatures like a lion-headed eagle. The Stele of the Vultures, made by Eannatum of Lagash, is special. It shows different scenes that tell the story of Lagash's victory over Umma. These types of reliefs have been found in southern Mesopotamia and the Diyala region, but not in Upper Mesopotamia or Syria.

-

Bas-relief of a banquet and boating scene, 3000-2334 BCE, Kish (Sumer).

-

Votive relief of the priest Dudu, from the time of Entemena, found at Girsu. Around 2400 BCE.

Metalworking and Goldsmithing: Skilled Craftsmanship

Sumerian metallurgy (working with metals) and goldsmithing were very advanced. This is amazing because metals had to be imported into the region. Known metals included gold, silver, copper, bronze, lead, electrum, and tin. People were already mixing metals to create alloys during the Uruk period. Sumerians used bronze, but since tin was rare, they often used arsenic instead. Metalworking techniques included lost-wax casting (making molds from wax), plating, filigree (delicate wirework), and granulation (tiny metal beads).

Many metal objects have been found in temples and graves. These include dishes, weapons, jewelry, small statues, foundation nails, and other religious items. The most amazing gold objects come from the Royal Cemetery at Ur. These include musical instruments and all the items from Puabi’s tomb. Metal vases have also been found at other sites in southern Mesopotamia, like the Vase of Entemena at Lagash.

-

Vessel stand shaped like an ibex. Made of copper alloy with nacre and lapis lazuli inlays, using the lost-wax method (ED III).

-

Reconstructed headgear of Puabi, found in the Royal Cemetery at Ur (ED III).

-

Gold objects from the Royal Cemetery at Ur.

-

Animal-shaped pendants of gold, lapis lazuli and carnelian from Eshnunna.

-

Pearl, lapis lazuli, carnelian and silver beads from Tell Agrab (ED I).

Cylinder Seals: Ancient Signatures

Cylinder seals were used to prove that documents were real, like sales agreements. They also controlled access by sealing clay on storage room doors. The use of cylinder seals grew a lot during the ED period. This suggests that administrative tasks became more complex.

Before this period, many different scenes were carved on cylinder seals. This variety disappeared at the start of the third millennium. Instead, seals in southern Mesopotamia and the Diyala region mostly showed mythological and cultural scenes. During ED I, seal designs included geometric shapes and simple pictures. Later, fighting scenes between real and mythical animals became common. Heroes fighting animals were also popular. Their exact meaning is not clear. Common mythical creatures included bull-men and scorpion-men. Real animals included lions and eagles. Some human-like creatures were probably gods, as they wore a horned crown, a symbol of divinity.

Scenes about religious practices, like banquets, became common during ED II. Another common ED III theme was the "god-boat," but its meaning is unknown. During ED III, people started registering who owned which seals. Art in Upper Mesopotamia and Syria was heavily influenced by Sumerian cylinder seal designs.

Inlays: Colorful Decorations

Examples of inlay have been found at several sites. They used materials like nacre (mother of pearl), white and colored limestone, lapis lazuli, and marble. Bitumen (a tar-like substance) was used to hold the inlay in wooden frames. But these wooden frames have not survived. The inlay panels usually showed mythological or historical scenes. Like bas-reliefs, these panels help us understand early forms of storytelling art. However, this type of art seems to have been less common in later periods.

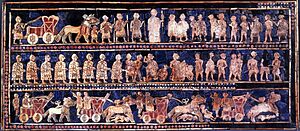

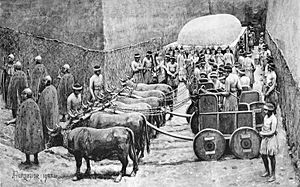

The best-preserved inlaid object is the Standard of Ur. It was found in one of the royal tombs in Ur. It has two main sides: one shows a battle, and the other shows a banquet, probably after a military victory. The "dairy frieze" found at Tell al-'Ubaid shows scenes of dairy farming, like milking cows and preparing dairy products. This gives us a lot of information about this practice in ancient Mesopotamia.

Similar mosaic pieces were found at Mari. There, a workshop for carving mother-of-pearl was discovered. At Ebla, marble fragments were found from a 3-meter-high panel that decorated a royal palace room. The scenes from Mari and Ebla are very similar in style and theme. In Mari, the scenes are military (a parade of prisoners) or religious (a ram's sacrifice). In Ebla, they show a military victory and mythical animals.

Music: Ancient Sounds

The Lyres of Ur (also called Harps of Ur) are thought to be the world's oldest surviving stringed instruments. In 1929, archaeologists led by Leonard Woolley found these instruments. They were digging at the Royal Cemetery of Ur between 1922 and 1934. They found pieces of three lyres and one harp in Ur, which was in Ancient Mesopotamia (now Iraq). These instruments are over 4,500 years old, from the ED III period. The decorations on the lyres are beautiful examples of the royal Art of Mesopotamia from that time.

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |