Indus Valley civilization facts for kids

|

|

| Alternative names | Harappan civilisation ancient Indus Indus civilisation |

|---|---|

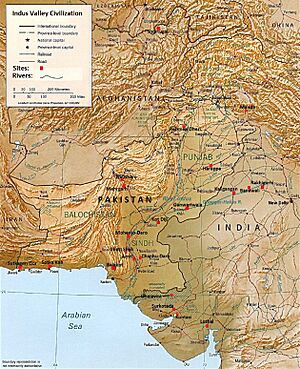

| Geographical range | Basins of the Indus river, Pakistan and the seasonal Ghaggar-Hakra river, northwestern India and eastern Pakistan |

| Period | Bronze Age South Asia |

| Dates | c. 3300 – c. 1300 BCE |

| Type site | Harappa |

| Major sites | Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, Ganweriwala, Dholavira, and Rakhigarhi |

| Preceded by | Mehrgarh |

| Followed by | Cemetery H culture Black and red ware Ochre Coloured Pottery culture Painted Grey Ware culture |

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC) was an ancient civilization in South Asia. It existed during the Bronze Age, from about 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE. Its most developed period was from 2600 BCE to 1900 BCE. This civilization was one of the first three great civilizations of the ancient world. The others were ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia.

The Indus Valley Civilisation was the largest of these three. It covered parts of modern-day Pakistan, northwestern India, and northeastern Afghanistan. It thrived along the Indus River and other rivers fed by seasonal rains.

The civilization is also called the Harappan Civilisation. This name comes from Harappa, one of its first discovered cities. Harappa was excavated in the early 20th century. Another major city was Mohenjo-daro. These cities were known for their amazing urban planning and advanced systems.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The Indus Civilisation gets its name from the Indus River. This river system is where its first sites were found.

Sometimes, it's also called the Harappan Civilisation. This is because Harappa was the very first site discovered and excavated in the 1920s.

Where in the World Was It?

The Indus Valley Civilisation existed at the same time as other great ancient civilizations. These included Ancient Egypt along the Nile River and Mesopotamia between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. It was also active when China's early civilization developed along the Yellow River.

At its peak, the Indus Civilisation was the largest of these. It stretched over a huge area. This included a core region of about 1,500 kilometers (930 miles) along the Indus River and its branches. Its cultural influence spread even wider.

Around 6500 BCE, farming began in Balochistan, near the Indus plains. Over thousands of years, settled life grew in the Indus plains. This led to the development of villages and then cities. The large cities of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa likely had populations of 30,000 to 60,000 people. At its height, the entire civilization might have had between one and five million people.

The civilization reached from Balochistan in the west to western Uttar Pradesh in the east. It went from northeastern Afghanistan in the north to Gujarat in the south. Many sites are found in the Punjab region, Gujarat, Haryana, and Rajasthan. Coastal towns like Sutkagan Dor and Lothal also existed.

How We Found This Lost World

The first modern reports of the Indus Civilisation's ruins came from Charles Masson in 1829. He was a traveler who explored the Punjab region. Masson was amazed by the large size of the ancient city of Harappa. He saw many historical artifacts half-buried there.

Later, in the mid-1800s, many bricks from Harappa were used to build railway lines. This caused a lot of damage to the ancient site.

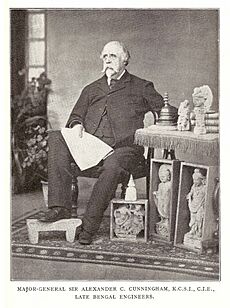

In 1861, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) was formed to protect historical sites. Alexander Cunningham, its first director, visited Harappa. He found a unique stamp seal with an unknown writing system. He realized it was from a very old, unknown culture.

Years later, John Marshall became the head of the ASI. He sent archaeologists to excavate Harappa. One of them was Daya Ram Sahni.

Further south, another important site, Mohenjo-daro, was discovered. R. D. Banerji visited Mohenjo-daro in the early 1920s. He realized it was incredibly ancient and similar to Harappa.

By 1924, John Marshall understood the huge importance of these discoveries. He announced to the world that a long-forgotten civilization had been found in the Indus plains. This led to more systematic excavations at both Mohenjo-daro and Harappa.

After India became independent in 1947, many Indus Valley sites were in Pakistan. Both India and Pakistan continued to explore and excavate these ancient cities. Today, we know of over 1,000 Harappan sites. The five largest cities are Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, Dholavira, Ganeriwala, and Rakhigarhi.

A Timeline of the Indus Civilisation

The Indus Valley Civilisation had different stages of development.

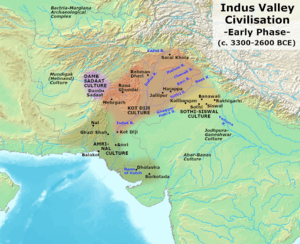

- Early Harappan Phase (around 3300–2600 BCE): This was when villages and early towns started to grow. People began farming and trading more.

- Mature Harappan Phase (around 2600–1900 BCE): This was the peak of the civilization. Large, well-planned cities developed. This is the period we usually think of when we talk about the Indus Valley Civilisation.

- Late Harappan Phase (around 1900–1300 BCE): During this time, the big cities began to decline. People moved to smaller settlements.

Before the Early Harappan phase, there was an even older period. This included sites like Mehrgarh, where farming first began in the region around 7000 BCE.

Early Beginnings: Mehrgarh

Mehrgarh is a very old site in Pakistan. It dates back to about 7000 BCE. It is one of the earliest places in South Asia with evidence of farming and herding. People here grew wheat and barley. They also raised animals like cattle. Mehrgarh helped set the stage for the Indus Valley Civilisation.

The Early Harappan Period

The Early Harappan period lasted from about 3300 BCE to 2800 BCE. During this time, farmers from the mountains slowly moved into the river valleys. They started to build larger settlements.

Trade networks began to connect these communities. They traded for valuable materials like lapis lazuli for making beads. People also grew many crops, including peas, sesame, dates, and cotton. They domesticated animals like the water buffalo.

By 2600 BCE, these early communities grew into large urban centers. This marked the beginning of the Mature Harappan phase.

The Mature Harappan Period

The Mature Harappan period, from 2600 BCE to 1900 BCE, was the golden age of the Indus Civilisation. Villages grew into large, well-organized cities. These cities were supported by successful farming, which relied on seasonal monsoon floods.

Archaeologists believe this civilization was a mix of different cultures. These cultures came together in the Ghaggar-Hakra valley. By 2600 BCE, major urban centers like Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, and Dholavira had developed.

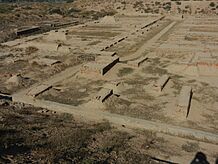

Amazing Cities and Planning

The cities of the Indus Valley Civilisation were very advanced. They had sophisticated urban planning and technology. This shows that there were well-organized local governments. These governments cared about public health and hygiene.

Cities like Harappa and Mohenjo-daro had the world's first known city sanitation systems. Homes had access to water from wells. Wastewater flowed into covered drains along the main streets. Houses usually opened into inner courtyards and smaller lanes.

These cities also had strong protective walls. These walls likely served as flood defenses and possibly as fortifications. Unlike other ancient civilizations, there were no large palaces or temples. Some buildings are thought to have been granaries for storing grain. The famous "Great Bath" at Mohenjo-daro might have been used for public rituals.

Most city dwellers were likely traders or artisans. They lived in neighborhoods with others who did the same work. The cities show a sense of fairness. All houses had access to water and drainage. This suggests a society where wealth was not extremely concentrated.

Who Was in Charge?

We don't know exactly who ruled the Harappan cities. However, the complex city planning and large public works show that there was some kind of authority. The consistent weights and measures used across the civilization also point to a central power.

There are two main ideas about their government:

- A single state or group ruled most of the Indus Valley.

- Each city was its own self-governing city-state.

Metalwork and Measurements

Harappans were skilled in metallurgy. They worked with copper, bronze, lead, and tin. They developed new techniques for metalworking.

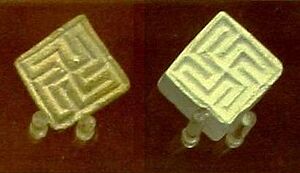

They were also very accurate in measuring. They had a system of uniform weights and measures. An ivory scale found in Lothal had the smallest divisions recorded on a Bronze Age scale, about 1.704 mm. Their weights followed a decimal system. This shows how advanced their engineering was.

Arts and Crafts

The Indus Valley people created many beautiful things. They made pottery, terracotta figurines, and a few stone sculptures. They also crafted gold jewelry and bronze vessels. Many small clay figures of animals and people were found, likely toys. They even made cubical dice for games.

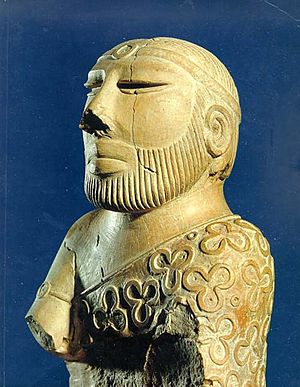

The most famous artworks are the statuettes. These include the bronze Dancing Girl and the Priest-King figure. These figures show amazing skill in representing the human body.

-

Ceremonial vessel; 2600–2450 BC; terracotta with black paint; 49.53 × 25.4 cm; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (US)

-

Cubical weights, standardized throughout the Indus cultural zone; 2600–1900 BC; chert; British Museum (London)

-

Mohenjo-daro beads; 2600–1900 BC; carnelian and terracotta; British Museum

Seals and Their Secrets

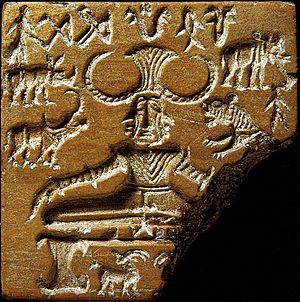

Thousands of steatite seals have been found. They are usually small squares with a pierced knob on the back. These seals often show animals, people, and a mysterious writing system. Some seals were used to stamp clay on trade goods.

One famous seal, the Pashupati seal, shows a seated figure surrounded by animals. Some scholars think this figure might be an early form of a god.

-

Seal; 3000–1500 BC; baked steatite; 2 × 2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Seal with two-horned bull and inscription; 2010 BC; steatite; overall: 3.2 x 3.2 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio, US)

Trade and Travel

The Indus Valley Civilisation had a wide trade network. They used bullock carts and boats for transportation. Their boats were likely small, flat-bottomed crafts, similar to those on the Indus River today.

They traded with distant regions like Mesopotamia, Central Asia, and the Iranian plateau. This trade involved goods like ceramics, seals, and ornaments. Some people even migrated to Indus cities from outside the valley.

Archaeological finds in places like Ras al-Jinz in Oman show that they had sea trade connections with the Arabian Peninsula.

Farming and Food

The Indus people were skilled farmers. They grew barley and a small amount of wheat. They also domesticated zebu cattle, which are still common in India today.

They were among the first to use complex multi-cropping. This means they grew different foods in both summer (like rice, millets, and beans) and winter (like wheat, barley, and pulses). This required careful management of water. They also developed their own type of rice farming.

Their diet included meats from animals like cattle, buffalo, goat, pig, and chicken. They also consumed dairy products. Recently, seven ancient food-balls, or "laddus," were found. They were made of legumes and cereals.

The Mystery of the Language

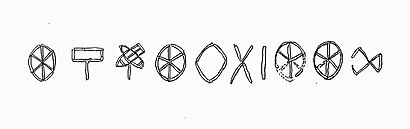

The language of the Indus Valley Civilisation is still unknown. The Indus script has not been deciphered. This means we cannot read their writings.

Scholars have different ideas about the language. Some think it might be related to the Dravidian languages, which are spoken in southern India and parts of Pakistan today.

A Possible Writing System

About 400 to 600 different Indus symbols have been found. They appear on seals, small tablets, and pottery. The longest inscription found has 34 symbols.

There is a debate about whether the Indus script is a true writing system. Some scholars believe it encoded a language. Others think it was a system of symbols for families, clans, or religious ideas, not a spoken language. The messages are very short, making them hard to decode.

Beliefs and Rituals

We don't know much about the religion of the Indus Valley people. This is because their writing hasn't been deciphered. We can only guess based on the artifacts they left behind.

Archaeologists like John Marshall suggested some ideas. They thought there might have been a Great Male God and a Mother Goddess. They also believed animals and plants were important in their beliefs. The use of baths and water, like the Great Bath, might have been for religious purification.

The famous Pashupati Seal shows a figure with a horned headdress surrounded by animals. Some scholars have linked this figure to early forms of certain gods from later Indian religions. However, these are just theories.

Unlike other ancient civilizations, there are no large temples or palaces. This suggests that religious ceremonies might have happened in homes or in open spaces.

The Decline of the Indus Civilisation

Around 1900 BCE, the Indus Civilisation began to decline. By 1700 BCE, most of the major cities were abandoned. Studies of human remains show an increase in violence and diseases during this time.

The Late Harappan phase saw a breakdown of the large city networks. People moved to smaller, more rural settlements.

Climate Change and Drought

Many scholars believe that climate change was a major reason for the decline. The climate became much cooler and drier from about 1800 BCE. This was due to a weakening of the monsoon rains.

The rivers that fed the Indus Valley depended on these monsoons. As the rains decreased, the water supply went down. This made farming difficult. People had to leave the cities and move eastward towards the Ganges basin. They formed smaller villages and farms. This led to the end of the great urban centers.

A New Chapter

The Indus Civilisation didn't just disappear. Many elements of its culture continued in later societies. New regional cultures emerged in the area. For example, the Cemetery H culture in the Punjab region showed some continuity with Harappan traditions.

Archaeological evidence shows that some Late Harappan settlements continued until about 1000–900 BCE. This means they existed at the same time as the early Vedic culture. The decline of the Indus cities led to a new phase of history in South Asia.

Images for kids

-

Reclining mouflon; 2600–1900 BC; marble; length: 28 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Male dancing torso; 2400–1900 BC; limestone; height: 9.9 cm; National Museum (New Delhi)

See also

In Spanish: Civilización del valle del Indo para niños

In Spanish: Civilización del valle del Indo para niños

- Cradle of civilization

- History of Hinduism

- History of Afghanistan

- History of India

- History of Pakistan

- List of Indus Valley Civilisation sites

- List of inventions and discoveries of the Indus Valley Civilisation

- Religion of the Indus Valley Civilization

- Sanitation of the Indus Valley civilisation

- Hydraulic engineering of the Indus Valley Civilization