Kish (Sumer) facts for kids

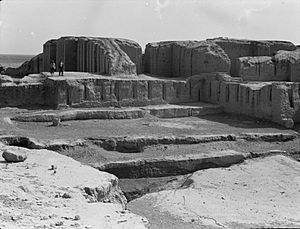

Ruins of Kish at time of excavation

|

|

| Location | Tell al-Uhaymir, Babil Governorate, Iraq |

|---|---|

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 32°32′25″N 44°36′17″E / 32.54028°N 44.60472°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | Ubaid period |

| Periods | Ubaid to Hellenistic |

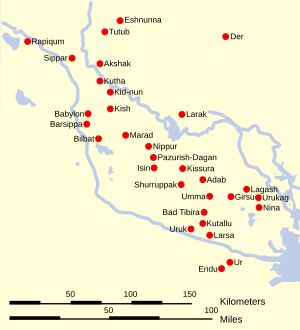

Kish was an important ancient city in Mesopotamia, which is now part of Iraq. It was located in the Babil Governorate. People lived in Kish for a very long time, from around 5300 BC until the Hellenistic period.

Contents

History of Kish

Kish was settled during the Ubaid period (around 5300-4300 BC). It became a very powerful city during the Early Dynastic Period. At its biggest, Kish covered an area of about 230 hectares (about 568 acres).

Early Kings and the Great Flood

An ancient list of kings, called the Sumerian King List, says that Kish was the first city to have kings after a huge flood. The first king mentioned was Ĝushur. After him, some kings had names that were actually Akkadian words for animals, like "scorpion." This shows that many people in Kish spoke Akkadian, a language similar to Hebrew or Arabic, from very early on.

After these kings, the Sumerians believed a massive flood hit Mesopotamia. According to their stories, the goddess Ishtar then gave the kingship to Etana. Etana was known as "the shepherd who went to Heaven." He is said to have brought peace and order to the land after the flood. Some even say Etana founded Kish.

One important king from Kish was Enmebaragesi. He is the first king from the list whose name has been found on actual ancient objects. He and his son, Aga of Kish, were known as rivals of Gilgamesh, a famous early ruler of Uruk.

Even after its most powerful time, Kish remained important. Many strong rulers from other cities, like Sargon of Akkad and kings from Ur or Babylon, would call themselves "King of Kish." This was a way to show they were powerful and connected to the city's long history. The main god of Kish was Zababa, along with his wife, the goddess Inanna.

Later Times in Kish

After the Akkadian Empire fell, Kish became a small independent kingdom again. Later, during the time of the First Dynasty of Babylon, Kish was taken over by other cities. Kings like Hammurabi and Samsu-iluna built new structures in Kish. Hammurabi even rebuilt the city's ziggurat (a large temple tower).

Over time, Kish became less important. By the time of the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian periods, the original city of Kish was mostly empty. The texts from this time that mention "Kish" were probably talking about a nearby settlement called Hursagkalama.

After the Achaemenid period, Kish is not mentioned much in history. However, archaeologists have found signs that people continued to live there for a long time. One part of the site, Tell Ingharra, became a large town during the Parthian period. It even had a big mud-brick fortress. The area around Kish continued to be settled during the Sasanian and early Islamic periods, finally being abandoned around the 13th century.

Archaeology of Kish

Kish is located about 80 kilometers (50 miles) south of Baghdad. The ancient site is a large oval area, about 8 by 3 kilometers (5 by 2 miles). It has about 40 mounds, which are hills covering ancient ruins. The biggest mounds are called Uhaimir and Ingharra.

Some of the most important mounds are:

- Tell Ingharra – This is thought to be the location of Hursagkalama, which had a temple dedicated to the goddess Inanna.

- Tell el-Bender – Here, archaeologists found objects from the Parthian period.

- Mound W – Many Neo-Assyrian clay tablets were found here.

Archaeologists started finding ancient tablets from Kish in the early 1900s. These tablets helped identify the site as the ancient city of Kish. Many different teams have excavated Kish over the years. A French team worked there from 1912 to 1914, finding about 1,400 Old Babylonian tablets. Later, a joint team from the Field Museum and University of Oxford excavated from 1923 to 1933. More recently, a Japanese team excavated at Tell Uhaimir in 1988, 2000, and 2001.

Tell Ingharra Discoveries

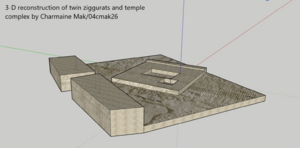

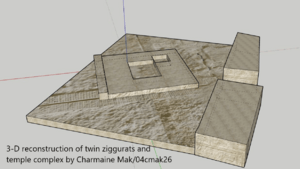

Tell Ingharra is on the eastern side of ancient Kish. It was explored a lot during the Chicago excavation. This area gave archaeologists a good idea of how the site developed during the 3rd millennium BC. The 1923 excavation focused on Mound E, which had two ziggurats (temple towers).

These twin ziggurats were built with special "plano-convex" bricks (bricks that are flat on one side and curved on the other). They were likely built around the end of the Early Dynastic IIIa period to honor the city. The temple complex found here was part of the city of Hursagkalama. It was used as a religious center until after 482 BC.

Area P Discoveries

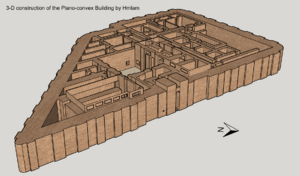

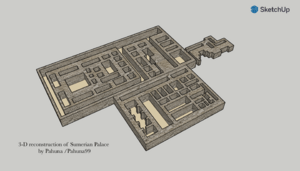

This area was explored during the second excavation season (1923-1924). Archaeologists found a large building called the 'Plano-convex building' (PCB) here. This building was made mostly of plano-convex bricks.

The PCB was not a religious building. Instead, it was likely a public building used for making things like beer, textiles, and oil. It might have also been an administrative center where important decisions were made. The building was destroyed twice during the late Early Dynastic III period, with signs of fire and weapons. After its destruction, it was abandoned.

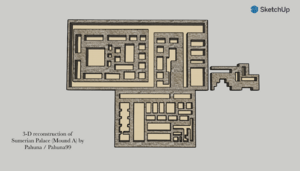

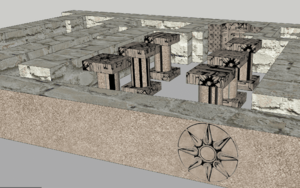

Mound A Discoveries

Mound A includes an ancient cemetery and a palace. It was discovered during excavations between 1922 and 1925. The palace was found beneath the mound. It had fallen into ruin and was used as a burial ground during the Early Dynastic III period.

The palace had very thick walls, especially in its original part. A wide passage was built within the outer wall to help protect it from invaders. Inside the palace, archaeologists found a piece of slate and limestone artwork. It shows a scene of a king punishing a prisoner.

Tell H Discoveries

Tell H was the focus of the last three seasons of the 1923-1933 expedition. This area showed many layers from different time periods. It was mainly identified as a Sasanian settlement, with eight buildings from that period. Researchers believe some of these buildings might have been part of a complex, possibly including a royal residence, storage areas, and administrative offices.

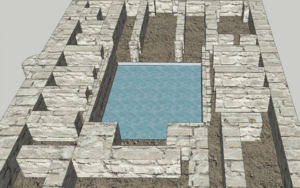

The most exciting finds were the stucco decorations in some of the buildings. These decorations helped researchers identify one building as a royal residence of Bahram V (420-438 AD), a Sasanian king. Kings had unique crown patterns, and the stucco showed Bahram V's crown. It is thought that Bahram V built palaces here for summer fun, which explains why one building has a huge water tank, probably to cool the court in hot weather.

Gallery

-

An Indus Valley Civilisation "Unicorn" seal found in Kish, from around 3000 BC. This shows how ancient people from the Indus Valley and Mesopotamia traded and connected.

See also

In Spanish: Kish para niños

In Spanish: Kish para niños

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |