Neo-Assyrian Empire facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Neo-Assyrian Empire

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 911 BC–609 BC | |||||||||||||||||||

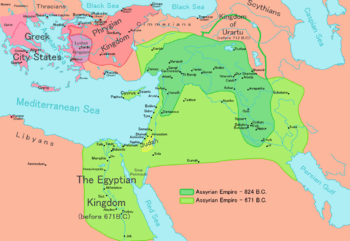

Map of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 824 BC (dark green) and in its apex in 671 BC (light green) under King Esarhaddon

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Aššur (911 BC) Kalhu (879 BC) Dur-Sharrukin (706 BC) Nineveh (705 BC) Harran (612 BC) |

||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Akkadian (official) Aramaic (official) Sumerian (declining) Hittite Hurrian Phoenician Egyptian |

||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Polytheism | ||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||||||||

|

• 911–891 BC

|

Adad-nirari II (first) | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• 612–609 BC

|

Ashur-uballit II (last) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Iron Age | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• Reign of Adad-nirari II

|

911 BC | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• Battle of Nineveh

|

612 BC | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• Siege of Harran

|

609 BC | ||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||

| 670 BC | 1,400,000 km2 (540,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Iraq Syria Israel Turkey Egypt Sudan Saudi Arabia Jordan Iran Kuwait Lebanon Cyprus Palestine |

||||||||||||||||||

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was a very powerful empire in Mesopotamia during the Iron Age. It existed from 911 BC to 609 BC. For a long time, it was the largest empire the world had ever seen.

Many historians believe it was the first true empire in history. The Neo-Assyrians were also very good at war. They were among the first to use iron weapons. They also had advanced and effective military tactics.

After King Adad-nirari II conquered many lands in the 900s BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew. It followed the Old Assyrian Empire and the Middle Assyrian Empire. It became the main power in the Ancient Near East. It also controlled parts of the East Mediterranean, Asia Minor, the Caucasus, the Arabian Peninsula, and North Africa.

The empire conquered and lasted longer than many rivals. These included Babylonia, Elam, Persia, Urartu, and Ancient Egypt.

The empire started to weaken around 631 BC after King Ashurbanipal died. Many civil wars broke out. This allowed Cyaxares, King of Persia and the Medes, to team up with Nabopolassar, ruler of Babylonia. They decided to invade Assyria.

Assyria allied with Egypt, but both were defeated. The empire finally fell at the Siege of Harran in 609 BC. Even today, Assyrian people still live in Iran, Iraq, and other places.

Contents

History of the Neo-Assyrian Empire

How the Empire Grew (911-859 BC)

The military campaigns of King Adad-nirari II helped Assyria become a great power. He defeated the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt. He also conquered many lands like Elam, Urartu, and Media. He even removed the Nubians and Ethiopians from Egypt. Other lands like Phrygia had to pay tribute to Assyria.

Adad-nirari II and the kings after him also conquered areas that were only partly under Assyrian control before. They also moved groups of people like the Arameans and Hurrians. King Adad-nirari II also defeated Shamash-mudammiq of Babylonia twice.

The next three kings were also very strong. Tukulti-Ninurta II became king in 891 BC. He expanded the empire into Asia Minor and the Zagros Mountains. Then Ashurnasirpal II became king in 883 BC. He won back much of the land lost after the Middle Assyrian Empire fell. He also stopped an uprising by the Lullibi and Gutian people.

Ashurnasirpal II and his son, Shalmaneser III, were known for being tough rulers. They also loved art. Ashurnasirpal II moved the capital city to Kalhu.

Major Campaigns and Challenges (859-783 BC)

King Shalmaneser III led yearly military campaigns. He turned the capital into a military base. He also took control of important rival cities. Babylon was occupied, and Babylonia came under Assyrian rule. However, a big battle called the Battle of Qarqar in 853 BC against Aramean states ended in a tie.

By 849 BC, Carchemesh was taken. By 842 BC, Damascus had to pay tribute. The cities of Tyre and Sidon in Phoenicia also had to pay tribute in 841 BC.

A civil war started in Assyria in 828 BC. Shalmaneser III's oldest son, Ashur-nadin-aplu, and 27 cities rebelled. This allowed Babylonia, the Medes, and others to take back their land. Urartu also became more powerful in the region.

Shalmaneser III's second son, Shamshi-Adad V, finally ended the civil war in 824 BC. This was the same year his father died. Shamshi-Adad V spent most of his reign trying to win back lost land. He died in 811 BC. His wife, Queen Sammuramat, ruled for a short time. Then their son Adad-nirari III became king in 806 BC.

Adad-nirari III was a very active king. He invaded The Levant. He also made the Arameans, Phoenicians, and Israelites obey Assyria. He made Damascus pay tribute again. He invaded Persia and made the Persians, Medes, and Manneans obey him. He also conquered tribes in southern Mesopotamia.

Times of Trouble and Change (783-745 BC)

After Adad-nirari III died in 783 BC, the empire had a period of stagnation, meaning it didn't grow much. King Shalmaneser IV had only small victories against Urartu and other groups. He died in 773 BC.

Then, more civil wars happened during the reigns of Ashur-dan III (772-754 BC) and Ashur-nirari IV (754-745 BC). There were uprisings in several cities. Assyria failed to invade other lands. There was also an outbreak of plague and a solar eclipse. The eclipse was seen as a bad omen, or sign.

Ashur-nirari IV was removed from power by a general named Pulu. Pulu then became king and changed his name to Tiglath-Pileser III in 745 BC. He brought Assyria back to power.

Tiglath-Pileser III's Reforms (744-727 BC)

When Tiglath-Pileser III became king in 744 BC, Assyria faced civil war and disease. They had also lost a war with Urartu. However, Tiglath-Pileser III made huge changes to how Assyria was run. He made the empire more secure and efficient. He changed how the provinces were managed.

Images for kids

-

Assyrian borders and campaigns under Ashur-dan II (r.934–912 BC), Adad-nirari II (r.911–891 BC) and Tukulti-Ninurta II (r.890–884 BC)

-

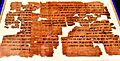

Annals of Tukulti-Ninurta II (r.890–884 BC), recounting one of his campaigns

-

Stele of Ashurnasirpal II (r.883–859 BC)

-

Stele of Shamshi-Adad V (r.824–811 BC)

-

Stele of Bel-harran-beli-usur, a palace herald, made in the reign of Shalmaneser IV (r.783–773 BC)

-

Partial relief depicting Tiglath-Pileser III (r.745–727 BC)

-

20th-century illustration of Tiglath-Pileser III's capture of Damascus

-

20th-century reconstruction of Sargon II's palace at Dur-Sharrukin

-

Line-drawing of a relief depicting Sennacherib (r.705–681 BC) on campaign in a chariot

-

Esarhaddon (r.681–669 BC), as depicted in his victory stele

-

20th-century illustration of the Assyrians capturing Memphis, the Egyptian capital, during the Assyrian conquest of Egypt

-

Relief depicting Ashurbanipal (r.669–631 BC) in a chariot, armed with a bow

-

Impression of a seal possibly belonging to the eunuch usurper Sin-shumu-lishir (r.626 BC)

-

Fall of Nineveh (1829) by John Martin

-

20th-century illustration of the Battle of Carchemish

-

Line-drawing of a Neo-Assyrian relief showing soldiers forming a phalanx

-

Neo-Assyrian cuneiform tablet from the Library of Ashurbanipal listing synonyms

-

Line drawing of an Assyrian lion weight once belonging to the king Shalmaneser V (r.727–722 BC). The inscriptions on the weight are in both Akkadian (on the body) and Aramaic (on the base).

-

Reconstruction of the Library of Ashurbanipal

-

Relief depicting the gardens of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh (left) with a color reconstruction (right). As can be seen on the right side of the relief, the garden featured sophisticated irrigation aqueducts.

-

Egyptian papyrus from c. 500 BC containing the Story of Ahikar

-

The Defeat of Sennacherib by Peter Paul Rubens

-

1861 illustration by Eugène Flandin of excavations of the ruins of Dur-Sharrukin

-

Portrait of the Assyrian archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam c. 1854

-

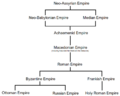

Chart depicting the ideological translatio imperii, i.e. supposed transfer of the right to universal rule, from the Neo-Assyrian Empire to (rival) early modern states claiming the same right

See also

In Spanish: Imperio neoasirio para niños

In Spanish: Imperio neoasirio para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |