Harran facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Harran

|

|

|---|---|

|

Settlement

|

|

|

|

Map showing Harran District in Şanlıurfa Province

|

|

| Country | Turkey |

| Province | Şanlıurfa |

| Established | c. 2500–2000 BC |

| Area | 904 km2 (349 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 360 m (1,180 ft) |

| Population

(2022)

|

96,072 |

| • Density | 106.27/km2 (275.25/sq mi) |

| Time zone | TRT (UTC+3) |

| Postal code |

63510

|

| Area code | 0414 |

Harran is a town and district in Şanlıurfa Province, Turkey. It covers an area of 904 square kilometers. In 2022, about 96,072 people lived there. Harran is located about 40 kilometers (25 miles) southeast of Urfa. It is also about 20 kilometers (12 miles) from the Syrian border.

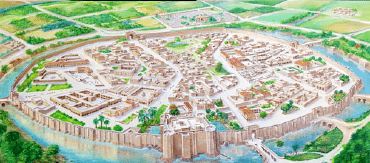

Harran is a very old city, founded between 2500 and 2000 BC. It might have started as a trading post for Sumerian merchants. Early on, Harran became a major center for culture, trade, and religion in Mesopotamia. It was especially important because of its connection to the moon-god Sin. Many powerful rulers visited and improved Sin's temple, called Ekhulkhul. Harran later became a key city under Assyrian rule. It was often the second most important city after the capital, Assur. During the fall of the Assyrian Empire, Harran was briefly its last capital (612–609 BC).

The city stayed important even after Assyria fell. It was ruled by many empires, including the Neo-Babylonians and Persians. Later, the Romans and Parthians often fought over Harran. In 53 BC, the famous Battle of Carrhae happened here. It was one of the worst defeats for the Roman army. The moon cult of Sin lasted a very long time in Harran, even into the 11th century AD. Harran was taken by the Rashidun Caliphate in 640 AD. It became an important city in the Islamic world. It was home to the first Islamic university and the oldest mosque in Anatolia. Harran was a capital city twice during the Middle Ages. It was the capital for the Umayyad Caliphate (744–750) and later for the Numayrid Emirate (990–1081).

The Mongol Empire conquered Harran in 1260. However, they largely destroyed the city and left it empty in 1271. For the past five centuries, Harran has mostly been a temporary home for nomadic groups. It became a semi-permanent village again in the 1840s. Recently, it has grown into a permanent town thanks to new ways of watering crops. Harran became a district again in 1987. Today, it is a popular place for tourists. The town is famous for its unique beehive houses. These houses look like buildings from ancient Mesopotamian times.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name Harran has been used for the city since ancient times. It has stayed mostly the same. In old writings, it was called Ḫarrānu, which means "journey," "caravan," or "crossroad." This often means "caravan path" or "where routes meet."

The ancient Assyrians called the city Huzirina. Later, the Greeks called it Kárrhai. The Romans then changed it to Carrhae. Because both Harran and Carrhae are famous in history, some people call the ancient city "Carrhae-Harran." Under the Byzantine Empire, it was still called Carrhae. Sometimes, it was also called Hellenopolis, meaning "city of the pagan Greeks." This was because of its strong pagan traditions.

A Look at Harran's Past

Uncertain; independent? c. 2500/2000–1800 BC

Shamsi-Adad's kingdom c. 1800–1775 BC

Independent c. 1775–1550? BC

Kingdom of Mitanni c. 1550–1300 BC

Assyrian Empire c. 1300–610 BC

Babylonian Empire 610–539 BC

Achaemenid Empire 539–330 BC

Empire of Tigran the Great (Armenia) IV c. BC

Macedonian Empire 330–312 BC

Seleucid Empire 312–132 BC

Kingdom of Osroene (Parthian vassal) 132 BC–AD 165

Roman Empire (1st time) 165–240

Sasanian Empire (1st time) 240–242

Roman Empire (2nd time) 242–549

Sasanian Empire (2nd time) 549–562?

Roman/Byzantine Empire (3rd time) 562?–640

Rashidun Caliphate 640–661

Umayyad Caliphate 661–750

Abbasid Caliphate 750–890

Hamdanid Emirate 890–990

Numayrid Emirate 990–1081

Uqaylid Emirate 1081–1102

Seljuk Empire (Jikirmish) 1102–1106

Artuqid State 1106–1127

Zengid Emirate 1127–1182

Ayyubid Sultanate (1st time) 1182–1237

Khwarazmians 1237–1240

Ayyubid Sultanate (2nd time) 1237–1240

Mongol Empire 1260–1271

Mamluk Sultanate 1270s–1517

Ottoman Empire 1517–1922

Republic of Türkiye 1922–present

Ancient Times (2500 BC–539 BC)

Early Beginnings

Harran is located at an important crossroads. It sits between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. It is also on the border between ancient Mesopotamian and Anatolian cultures. The first known settlements in this area date back to 10000–8000 BC. Harran itself was likely founded around 2500–2000 BC. It was probably a trading post for merchants from the Sumerian city of Ur.

From early on, Harran was linked to the Mesopotamian moon-god Nanna, later known as Sin. It quickly became a sacred city for the moon. The Ekhulkhul, Harran's great moon temple, was already there by 2000 BC. The moon was important in Ur, where Sin's main temple was. Harran's hot, dry climate might also explain its focus on the moon. The night, with the moon, offered comfort from the harsh sun.

The religious leaders of Harran, speaking for Sin, were important in political agreements. Around 2000 BC, a peace treaty was signed in the Ekhulkhul temple. This shows how much power the city's religious leaders had. Harran grew into a major cultural, trade, and religious hub. Its location on key trade routes made it very important.

Under Assyrian and Babylonian Rule

The Assyrian king Adad-nirari I (1305–1274 BC) conquered Harran from Mitanni. Under Assyrian rule, Harran became a strong provincial capital. It was often second in importance only to the capital, Assur. In the 10th century BC, Harran was one of the few cities that did not have to pay tribute to the Assyrian king.

Because Harran was the sacred city of the moon-god, many Mesopotamian kings visited it. They sought blessings and confirmation of their rule from the city's religious leaders. In return, they improved Harran and its temples. The Ekhulkhul temple was rebuilt twice during the Neo-Assyrian period. Prophecies from Harran's moon cult were highly respected.

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was defeated in the late 7th century BC. The capital, Nineveh, fell in 612 BC. The rest of the Assyrian army gathered at Harran. So, Harran became the last capital of ancient Assyria for a short time. After a long siege, Harran was captured by the Babylonians and Medes in 609 BC. This ended the Neo-Assyrian Empire. The Ekhulkhul temple was destroyed then. But it was later rebuilt by the Neo-Babylonian king Nabonidus (556–539 BC), who was from Harran.

Later Ancient Times (539 BC–640 AD)

After the Neo-Babylonian Empire fell in 539 BC, Harran was ruled by several empires. These included the Persians, Macedonians, and Seleucids. Under the Seleucids, many Greeks settled in Harran. This led to some Greek cultural influence. After the Seleucid Empire broke apart, Harran became part of the Kingdom of Osroene in 132 BC. This kingdom was often a vassal state of the Parthian Empire.

From the 1st century BC, Harran was often near the border of the Roman (later Byzantine) and Parthian (later Sasanian) empires. The city changed hands often. In 53 BC, Harran was the site of the Battle of Carrhae. In this battle, the Parthians defeated the Romans. The Roman emperor Caracalla was murdered in Harran in 217 AD while visiting the temple of Sin.

Harran had a strong rivalry with the nearby city of Edessa. Edessa quickly became Christian, but Harran remained a pagan stronghold for centuries. It was the biggest center for pagan cults in eastern Syria. Even in the 4th century, Harran was mostly pagan. Despite this, Christians were interested in Harran. The city is mentioned in the Book of Genesis as where Abraham and his family stopped.

The last pagan Roman emperor, Julian, visited Harran in 363 AD. He wanted to ask the moon temple's oracles about his upcoming war. The oracles warned him of disaster, but Julian went ahead and was killed. Harran was the only city in the Roman Empire to mourn Julian's death. The pagans of Harran became a problem as the Roman Empire became more Christian. In 590 AD, Emperor Maurice ordered the persecution of Harran's pagans. Many who refused to convert were executed.

Middle Ages (640–1271)

Harran Under Islamic Rule

The persecution of pagans by Emperor Maurice did not stop the pagan community in Harran. When the armies of the Rashidun Caliphate besieged Harran in 639–640, the city's pagans negotiated its peaceful surrender. Harran became a very important city under Islamic rule.

Under the Umayyad Caliphate (661–750), Harran was rebuilt and became prosperous again. In 717, Caliph Umar II founded the first Muslim university in Harran. Many scholars came to Harran from other cities. Harran became the capital of the Umayyad Caliphate from 744 to 750 under its last caliph, Marwan II. This move caused some anger, but Harran kept special privileges under the next caliphate, the Abbasid Caliphate.

The Harran University had its best period in the 8th century. This was especially true under the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid (786–809). Many important scholars studied mathematics, philosophy, medicine, and astrology there. The university was also key for translating documents into Arabic. Harran became a center of science and learning.

The local religion in Harran continued to be a mix of ancient Mesopotamian religion and Neoplatonism. Harran was known for its strong pagan traditions even in the Islamic period. The city had a very diverse population with many different religions. Some people adopted faiths that Muslims accepted. Others continued to worship the old gods of Mesopotamia and Syria. Some mainly worshipped the stars and planets.

In 830, Caliph Al-Ma'mun (813–833) came to Harran with his army. He planned to destroy the city because of its large pagan population. He asked the people if they were Muslims, Christians, or Jews. These groups were protected under Islamic law. The people of Harran said they were "Sabians," a mysterious religious group also protected by the Quran. They claimed their prophet was Hermes Trismegistus. Some Islamic writers did not believe this and still saw them as pagans. In 933, Harran's pagans were ordered to convert to Islam. But even after this, some pagan religious leaders still ran a public temple.

Late Middle Ages

The power of the Abbasid Caliphate and its local rulers weakened in the late 10th century. A new local Arab family, the Numayrid dynasty, took control. They ruled a small area with Harran as its capital from 990 to 1081. The acceptance of paganism in Harran finally ended in the 11th century. The last moon temples were closed and destroyed. By the 1180s, Harran was fully Islamic.

In the late 11th and early 12th centuries, northern Mesopotamia and Syria were divided. Harran was important to Muslim rulers as a defense against the nearby crusader states. The Harran Castle, likely built by the Byzantines, was rebuilt and made stronger in 1059. The growth of Edessa under Christian rule may have caused Harran to decline. Edessa had more wells, which caused Harran's wells to dry up.

Despite water problems, Harran remained important under the Ayyubid Sultanate. Saladin (1174–1193) expanded Harran's Grand Mosque. Harran was captured by the Mongol Empire in 1259 or 1260. The Mongols decided to leave Harran in 1271. They moved the people to other cities like Mardin and Mosul. The city was likely destroyed or damaged when they left. A main reason for leaving was the lack of water. It was hard to support Harran's population with broken water systems and dry wells.

Recent History (1271–Present)

The Mamluk Sultanate took Harran back from the Mongols in the 1270s. The Mamluks repaired the castle, but they did not try to rebuild the city much. By this time, Harran was no longer on major trade routes. A small village grew up near the castle. Over centuries, dirt and sand covered most of Harran's old buildings. Only the castle and the mosque remained visible.

Under the Ottoman Empire, Harran was a local administrative center. The damaged Harran University was repaired by Sultan Selim I (1512–1520). But it declined again after his rule. The Ottomans used the castle and built a new, smaller mosque. However, Harran slowly declined and eventually became a temporary settlement.

For the last 500 years, Harran has mostly been used by nomadic groups. By the 1840s, it was a semi-permanent village again. But people still left in summer to avoid pests. By the mid-20th century, Harran had about 100 houses. Its old water systems were broken. The city had only one source of drinking water, Jacob's Well.

Since the mid-20th century, Harran has become a permanent settlement again. This is due to new irrigation and farming methods. The Turkish Southeastern Anatolia Project, started in the 1970s, helped a lot. It turned the dry desert plains around Harran into rich farmland. Harran's ancient ruins were added to the Tentative list of World Heritage Sites in Turkey in 2000. Economic problems from the nearby Syrian civil war have caused some Harranian families to move away for work.

Town Features

Old Buildings and Ruins

The Harran Castle is a large brick fortress. Its exact age is unknown. It might have been built during Byzantine rule (4th–7th centuries) or under Muslim rule in the 9th century. The castle was once a three-story building. It was likely a palace first, then became a military fortress. The castle has been partly dug up and rebuilt with help from the Turkish government.

Harran was home to the oldest mosque in Anatolia. It is known as the Grand Mosque or Paradise Mosque. The Umayyad caliph Marwan II built it between 744 and 750. The mosque was very large, but little of it stands today. Parts that remain include the eastern wall, the mihrab (prayer niche), a fountain, and the 33.3-meter (109-foot) tall minaret.

Another important historical site is Harran's ancient burial mound. It is a large hill with old inscriptions and building parts. It was used from the 3rd century BC to the 13th century AD. It might even be older than Harran itself.

The exact spot of the ancient Ekhulkhul temple is unknown. It is likely that one of Harran's major medieval buildings was built on top of it. This could be the Harran Castle or the Grand Mosque. Many writings from the Islamic period say that either the castle or the mosque was the converted moon temple. Finds at the mosque, like Babylonian inscriptions and an altar with moon symbols, suggest it is the more likely site.

City Walls

The old town of Harran is still mostly surrounded by its ancient city walls. Many parts are in poor condition, but some sections are well-preserved. This gives an idea of how the city once looked. The exact date of the current walls is not known. They were most likely built under Roman or Byzantine rule.

Harran's walls are similar to those of nearby Edessa. They are roughly oval-shaped, about 3 meters (10 feet) thick. They are about 4.5 kilometers (2.8 miles) long and 5 meters (16 feet) high. The walls once had 187 towers and 6–8 gates. Most of these are now in ruins. Only one medieval gate, the Aleppo Gate, still stands. The walls were once surrounded by a large moat filled with water.

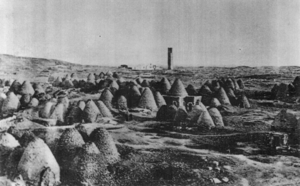

Unique Beehive Houses

Harran is famous for its special local architecture. These are the beehive houses, also called kümbets. This type of building is rare in Turkey and the world. Houses similar to these have been in Harran for a long time. The earliest known buildings from Harran were round. Assyrian carvings from the 7th century BC show domed buildings like today's beehive houses.

Most of the beehive houses you see today were built in the early 20th century. None have been standing since before the mid-19th century. Their design has changed a bit over time. Older photos show them built like tents. Today's conical domes sit on larger square bases.

Wood is scarce in Harran's climate. So, locals traditionally built houses from stone, brick, and mud. The modern beehive houses were built by locals who learned from old excavated buildings. They even used bricks from the ruins. These houses were good for nomadic life. They could be built and taken down quickly, like a tent. They also keep out heat and cold well. Their thick walls (50–60 cm or 20–24 inches) and domes (20–30 cm or 8–12 inches) help. The domes have an opening at the top for air. This keeps the inside cool in summer.

In 2002, there were 2,760 beehive houses in Harran. Now, only a few dozen remain in the old town. Some were lived in until the 1980s. Today, they are mostly used for storage or as barns. They have been protected since 1979. One of the oldest beehive buildings is now the Harran Culture House. It is a local museum and restaurant. It was built around 1800, then rebuilt in 1999 for tourism. The museum shows artifacts, jewelry, and traditional clothes.

Modern Buildings

Since the 1950s, rules have stopped locals from taking building materials from the ancient ruins. So, newer houses in Harran are mostly concrete buildings. They do not look like the beehive houses. Concrete houses are built both next to beehive houses and outside the old city walls. Most of Harran's people now live in a newer village. It is about 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) from the old city center.

Location and Weather

Harran is in the Southeastern Anatolia Region of Turkey. It is about 40 kilometers (25 miles) southeast of Urfa. Harran is 360 meters (1,180 feet) above sea level. This is the lowest point in the surrounding flat area.

Harran has a hot and dry climate. It rarely gets more than 40 centimeters (16 inches) of rain. In summer, the temperature changes a lot between day and night.

People of Harran

In its busiest times, Harran probably had about 10,000–20,000 people.

Harran's population has grown quickly since the late 20th century. This is because it became a permanent settlement again. Even with this growth, Harran is still mostly rural. In 2022, Harran had 96,072 people. The Harran district ranks low in Turkey for its economic development. It has low unemployment but also a low literacy rate.

In the 17th century, the area around Harran was home to Bedouin tribes. The local culture is mostly Arabic in how people live, dress, and eat. Harran has strong social, cultural, and business ties with Urfa. Most of the people in the district are tribal Arabs.

Languages Spoken

A census in 1927 showed that 88.0% of Harran's people spoke Arabic as their first language. 6.8% spoke Kurdish, and 5.2% spoke Turkish. By 1998, most people in Harran spoke Turkish. About 19% spoke Arabic, and 10% spoke Kurdish.

Visiting Harran

The ancient ruins in Harran are like an open-air museum. The town is a popular local tourist spot. Many people visit it on a day trip from Urfa. Popular places to see include the Harran Culture House and the ruins of the castle and mosque. Before 2015, Harran had about two million visitors a year. The Syrian civil war nearby has greatly reduced this number.

Digging Up the Past

Historians were very interested in Harran because of its ancient moon cult and its many mentions in old writings. But the site itself did not get much archaeological attention until the 19th century. This was because it was far away and hard to reach. Harran first got attention in 1850.

Early visitors only looked at the ruins on the surface. They did not dig. Later, in the 1950s, archaeologists like Seton Lloyd and R. Storm Rice led expeditions. They cleared rubble and mapped the city walls. Rice also dug up the ruins of the Grand Mosque. Digging at Harran has been limited. This is partly due to its remote location and political issues. It is also hard for foreign archaeologists to work in Turkey.

In 2012 and 2013, the Şanlıurfa Museum Directorate started more extensive digs. They focused on the walls, burial mound, and castle. These digs were mainly to restore the western city wall. They uncovered walls, towers, and bastions. In 2014, more digging found a bathhouse, a bazaar, public toilets, and a perfumery shop. In 2016, new parts of the city wall were found. They also found a broken statue of a woman and a male carving used in the wall. More digs in 2017–2018 found parts of a bathhouse in the southern castle.

Famous People from Harran

- Oracle of Nusku, Assyrian prophetess (around 671–670 BC)

- Adad-guppi, Assyrian priestess (around 648–544 BC)

- Nabonidus, last Neo-Babylonian king (556–539 BC)

- Jabir ibn Hayyan, alchemist and writer (died 806/816)

- Asad ibn al-Furat, legal expert, religious scholar, and general (around 759–828)

- Thābit ibn Qurra, mathematician, astronomer, and translator (826/836–901)

- Al-Battani, mathematician and astronomer (around 858–929)

- Sinān ibn al-Fatḥ, mathematician (10th century)

- Hammad al-Harrani, scholar, poet, and traveler (11th–12th century)

- Ibn Hamdan, scholar and judge (1206–1295)

- Ibn Taymiyyah, legal expert and religious scholar (1263–1328)

Images for kids

-

Harran shown on the Arch of Septimius Severus in Rome.

See also

In Spanish: Harrán para niños

In Spanish: Harrán para niños

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |