- This page was last modified on 17 October 2025, at 10:18. Suggest an edit.

al-Battani facts for kids

"Albategnius" redirects here. For the lunar crater, see Albategnius (crater).

|

al-Battānī

|

|

|---|---|

| محمد بن جابر بن سنان البتاني | |

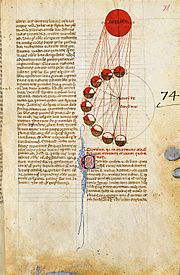

A folio from a Latin translation of Kitāb az-Zīj aṣ-Ṣābi’ (c. 900), Latin 7266, Bibliothèque nationale de France

|

|

| Born | before 858 Harran, modern-day Turkey

|

| Died | 929 Qasr al-Jiss, near Samarra

|

| Era | Islamic Golden Age |

Al-Battānī (full name: Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Jābir ibn Sinān al-Raqqī al-Ḥarrānī aṣ-Ṣābiʾ al-Battānī), also known as Albategnius, was a famous astronomer, astrologer, and mathematician. He lived and worked mostly in Raqqa, which is now in Syria. Many people consider him the greatest and most famous astronomer from the medieval Islamic world.

Al-Battānī's work was very important for science and astronomy in the Western world. His book, Kitāb az-Zīj aṣ-Ṣābi’ (around 900 AD), was one of the first detailed astronomical tables based on the Ptolemaic tradition. This means it followed the idea that Earth was the center of the universe. His book improved on the work of Ptolemy and added new ideas and tables. Later, his work was translated into Latin, which helped medieval astronomers learn from him. In 1537, a Latin version of his tables was printed, making his discoveries available to many more scholars.

Al-Battānī observed the Sun carefully. This helped him understand why annular solar eclipses happen. He accurately figured out the Earth’s tilt (the angle between the Earth's equator and its path around the Sun). He also calculated the length of the solar year and the equinoxes (when day and night are equal). His accurate data even encouraged Nicolaus Copernicus to think about the heliocentric idea, which says the Sun is the center of our solar system. Famous astronomers like Tycho Brahe, Johannes Kepler, Galileo Galilei, and Edmond Halley used al-Battānī's observations.

Al-Battānī also brought in the use of sines and tangents in geometry calculations. This was a big change from the older Greek methods. He used trigonometry to create a way to find the qibla, which is the direction Muslims face during their prayers. His method was widely used until better ways were found about a century later by al-Biruni.

Contents

Life of Al-Battānī

Al-Battānī, whose full name was Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Jābir ibn Sinān al-Raqqī al-Ḥarrānī al-Ṣābiʾ al-Battānī, was born before 858 in Harran, which is now in Turkey. His Latinized name was Albategnius. His father, Jabir ibn Sinan al-Harrani, made tools for studying the stars.

His family name, al-Ṣabi’, suggests they might have belonged to the Sabian group in Harran. This group worshipped stars and were very interested in math and astronomy. However, al-Battānī himself was a Muslim.

Between 877 and 918/919, he lived in Raqqa, Syria, which was an old Roman town near the Euphrates River. He also lived in Antioch for some time, where he observed solar and lunar eclipses in 901. Later in his life, al-Battānī faced money problems, which made him move from Raqqa to Baghdad.

Al-Battānī passed away in 929 in a place called Qasr al-Jiss, near Samarra. This happened after he returned from Baghdad, where he had helped a group from Raqqa with a tax problem.

Al-Battānī's Astronomy Discoveries

Al-Battānī is known as the most important astronomer of the medieval Islamic world. He made more accurate observations of the night sky than anyone else at that time. He was part of a new group of Islamic astronomers who came after the House of Wisdom was founded in the 8th century.

His detailed methods allowed others to check his work. However, some of his explanations about how planets move were not very clear and had mistakes.

Al-Battānī believed in Ptolemy's geocentric model, which means he thought the Earth was the center of the universe. He improved on Ptolemy's observations and created new tables for the Sun and Moon. These tables were considered very accurate for a long time.

He set up his own observatory in Raqqa. He suggested using large astronomical tools, bigger than 1 meter. These larger tools could measure smaller details, making his observations more precise than before. Some of his measurements were even more accurate than those made by Nicolaus Copernicus much later. This might be because Raqqa was closer to the Earth's equator. This meant the Sun and ecliptic (the Sun's path) were higher in the sky, so the air affected his observations less.

An annular solar eclipse. Al-Battānī was one the first astronomers to understand why such phenomena can occur.

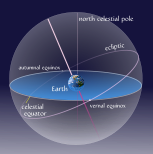

A representation of the celestial equator and Earth's ecliptic

Al-Battānī was one of the first to notice that the distance between the Earth and the Sun changes throughout the year. This helped him understand why annular solar eclipses happen. He saw that the point where the Sun looked smallest in the sky had moved from where Ptolemy said it should be.

He also improved Ptolemy's measurement of the Earth's tilt, finding it to be 23° 35'. The accepted value today is around 23.44°. He also calculated the length of the solar year as 365 days, 5 hours, 46 minutes, and 24 seconds. This is very close to the actual value, off by only about 2 minutes and 22 seconds.

Al-Battānī observed changes in the direction of the Sun's farthest point from Earth. His careful measurements of the March and September equinoxes helped him figure out the precession of the equinoxes. This is a slow wobble of Earth's axis, which changes the Sun's apparent path through the constellations. He calculated this change to be 1 degree every 66 years.

Even though al-Battānī made amazing observations, he still believed the Earth was still and at the center of the universe. Because of this, he couldn't fully understand the scientific reasons behind his own discoveries.

Al-Battānī's Mathematics Contributions

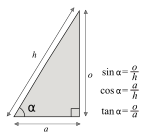

The fundamental trigonometric functions defined from a right-angled triangle: sine, cosine, and tangent

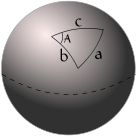

A spherical triangle with sides a, b, and c

One of al-Battānī's most important contributions was using sines and tangents in geometry calculations. He especially used them for spherical trigonometry, which deals with triangles on the surface of a sphere. This replaced the older methods used by the Greeks. Al-Battānī's methods used some of the most advanced math of his time.

He knew that trigonometry was better than using geometrical chords. He also showed how the sides and angles of a spherical triangle are related.

Al-Battānī also developed ways to calculate and create tables for both tangents and cotangents. He discovered their opposite functions, the secant and cosecant. He made the first table of cosecants for each degree from 1° to 90°. He called this a "table of shadows," because it related to the shadows cast by a sundial.

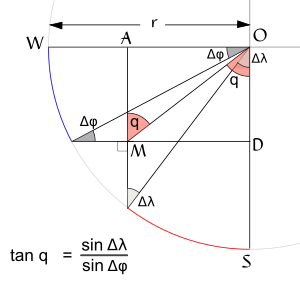

A geometrical representation of the method used by al-Battānī to determine the qibla, shown as q from O to M

Using these trigonometry ideas, al-Battānī created a way to find the qibla. This is the direction Muslims face during their five daily prayers. His method was widely used at the time. However, it did not give perfectly accurate directions because it didn't fully account for the Earth being a sphere. It was most accurate for people living near Mecca.

About a century later, al-Biruni found better methods that were more accurate than al-Battānī's.

Al-Battānī's Major Works

Kitāb az-Zīj aṣ-Ṣābi’

Al-Battānī's most famous work is Kitāb az-Zīj (meaning "Book of Astronomical Tables"), written around 900 AD. It is also known as al-Zīj al-Ṣābī. This book is one of the earliest complete zīj (astronomical tables) that followed the Ptolemaic tradition. It corrected mistakes made by Ptolemy and described tools like sundials, the triquetrum, and the quadrant.

The book has 57 chapters and many tables. It explains how to use the attached tables. Al-Battānī used an Arabic translation of Ptolemy's Almagest. He copied some data directly from Ptolemy's tables but also created his own. His star table from 880 AD used about half the stars found in Ptolemy's much older Almagest. He updated Ptolemy's star positions to account for the stars moving over time, which we now know is caused by precession.

The first Latin translation of his work was made by Robert of Ketton, but it is now lost. Another Latin translation was made by Plato Tiburtinus between 1134 and 1138. This translation, called De motu stellarum ("On stellar motion"), helped medieval astronomers learn a lot from al-Battānī. It was also translated into Spanish in the 13th century.

The invention of movable type printing in 1436 helped spread astronomical works more widely. A Latin translation of Kitāb az-Zīj aṣ-Ṣābi’ was printed in Nuremberg in 1537. This made al-Battānī's observations available at the start of the scientific revolution in astronomy. The book was reprinted in Bologna in 1645, and the original document is kept at the Vatican Library in Rome.

These Latin translations made his zīj very important for the growth of European astronomy. Later, the Italian scholar Carlo Alfonso Nallino published al-Battānī's work in three volumes between 1899 and 1907. This edition, though in Latin, is the basis for how we study medieval Islamic astronomy today.

Al-Battānī's Legacy

Influence in the Middle Ages

Al-Battānī's al-Zīj al-Ṣābī was very famous among Islamic astronomers. For example, the Arab scholar al-Bīrūnī wrote a book about al-Battānī's Zīj, though it is now lost.

Al-Battānī's work was key to the development of science and astronomy in the West. European astronomers used his work during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. He also influenced Jewish scholars like Abraham ibn Ezra and Gersonides. Moses Maimonides, a very important Jewish leader and thinker, closely followed al-Battānī's ideas.

Nicolaus Copernicus mentioned "al-Battani the Harranite" when talking about the paths of Mercury and Venus. He compared his own calculations with those from al-Battānī. The accuracy of al-Battānī's observations encouraged Copernicus to develop his ideas about the heliocentric universe (Sun at the center). In Copernicus's famous book, De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium, al-Battānī is mentioned 23 times!

16th and 17th Centuries

The German mathematician Christopher Clavius used al-Battānī's tables to help reform the Julian calendar. This led to the creation of the Gregorian calendar in 1582, which we still use today. Astronomers like Tycho Brahe, Johannes Kepler, and Galileo Galilei all referred to al-Battānī's work or observations. His calculation for the Sun’s eccentricity (how much its orbit is like an oval) was almost perfectly correct, even better than the values found by Copernicus and Brahe.

The lunar crater Albategnius was named after him in the 17th century. This was done by Giovanni Battista Riccioli, whose system for naming craters on the Moon became standard.

In the 1690s, the English astronomer Edmond Halley (famous for Halley's Comet) used a translation of al-Battānī's zīj. He discovered that the Moon's speed might be increasing. Halley used al-Battānī's calculations from Raqqa and Antioch to figure out the Moon's movement.

18th Century to Today

Al-Battānī's observations of eclipses were used by the English astronomer Richard Dunthorne to calculate how much the Moon's speed in its orbit was increasing. He found that the Moon's position was changing by 10 arcseconds per century.

Even today, al-Battānī's data is still used by geophysicists, who study the Earth's physical processes.

See Also

In Spanish: Al-Battani para niños

In Spanish: Al-Battani para niños

- List of Arab scientists and scholars