Giovanni Battista Riccioli facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Reverend

Giovanni Battista Riccioli

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Galeazzo Riccioli

17 April 1598 |

| Died | 25 June 1671 (aged 73) Bologna, Papal States

|

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Experiments with pendulums and with falling bodies Introducing the current scheme of lunar nomenclature |

| Parent(s) | Giovanni Battista Riccioli and Gaspara Riccioli (née Orsini) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy, experimental physics, geography, chronology |

Giovanni Battista Riccioli (born April 17, 1598 – died June 25, 1671) was an Italian astronomer and a Catholic priest from the Jesuit order. He is famous for his experiments with pendulums and falling objects. He also discussed many ideas about whether the Earth moves. Riccioli helped create the system we still use today for naming features on the Moon. He was also one of the first to discover that some stars are actually double stars.

Biography

Giovanni Riccioli was born in Ferrara, Italy. He joined the Jesuit order in 1614. After his training, he studied humanities, philosophy, and theology. From 1620 to 1628, he studied at the College of Parma. The Jesuits in Parma were very interested in experiments, especially with falling objects.

One of his teachers, Giuseppe Biancani, was a famous Jesuit astronomer. Biancani believed in new ideas, like mountains on the Moon. Riccioli admired his teacher very much.

Riccioli became a priest in 1628. He wanted to be a missionary, but his request was turned down. Instead, he was asked to teach in Parma. There, he taught different subjects and did experiments with falling objects and pendulums. He later taught in Mantua and Bologna.

Even though he was a theologian, Riccioli loved astronomy. He said that once he became interested in astronomy, he couldn't stop. His Jesuit leaders eventually told him to focus on astronomical research.

Riccioli built an astronomical observatory in Bologna. It had many tools like telescopes, quadrants, and sextants. He studied not only astronomy but also physics, math, and geography. He worked with other Jesuits, like Francesco Maria Grimaldi, and wrote letters to many famous scientists of his time.

The King of France, Louis XIV, even gave him an award for his important work. Riccioli kept publishing books on astronomy and theology until he died in Bologna at 73 years old.

Scientific Work

Almagestum Novum

One of Riccioli's most important books was his 1651 Almagestum Novum, which means New Almagest. This was a huge book, over 1500 pages long, filled with text, tables, and pictures. It became a key reference book for astronomers across Europe.

The book had ten main sections, called "books," covering everything known about astronomy at the time:

- The sky and how things move in it.

- The Earth, its size, and how objects fall.

- The Sun, its size, distance, and movement.

- The Moon, its phases, size, and distance. It included detailed maps of the Moon.

- Lunar and solar eclipses.

- The fixed stars.

- The planets and how they move.

- Comets and novae (new stars).

- The structure of the universe, including the Sun-centered and Earth-centered ideas.

- Calculations for astronomy.

Riccioli had planned for three volumes, but only the first one was finished.

Pendulums and Falling Objects

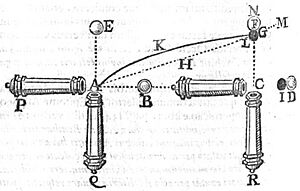

Riccioli was the first person to accurately measure how fast objects speed up when they fall due to gravity. He wrote a lot about his experiments with falling objects and pendulums in his New Almagest.

He used pendulums to measure time very precisely. He found that a pendulum's swing time is almost always the same. He tried to create a pendulum that would swing exactly once per second. He even had a team of nine other Jesuits help him count swings for 24 hours!

Riccioli used the tall Torre de Asinelli in Bologna to drop objects. With pendulums to time the falls, he could do very exact experiments. He confirmed that falling objects speed up at a steady rate, just as Galileo had said. For example, he found that a falling object travels 4.44 meters in one second and 17.76 meters in two seconds.

He also found that heavier objects fall slightly faster than lighter ones if they are made of different materials. He realized this difference was due to air resistance. Riccioli carefully described his experiments so that anyone could repeat them. His work helped prove some of Galileo's ideas about falling bodies.

Work Concerning the Moon

Riccioli and Grimaldi studied the Moon in great detail. Grimaldi drew maps of the Moon, which Riccioli included in his book. On these maps, Riccioli gave names to many features on the Moon. These names are still used today! For example, the Mare Tranquillitatis (Sea of Tranquility), where the Apollo 11 astronauts landed, was named by Riccioli.

He named large areas of the Moon after weather terms. He named craters after important astronomers, grouping them by their ideas. Even though Riccioli did not believe the Earth moved around the Sun, he named a large crater "Copernicus" after the astronomer who proposed that idea. He also named craters after other supporters of the Sun-centered theory, like Kepler and Galileo. Some people think this might have been a secret way for him to show support for their ideas, even though he couldn't openly agree as a Jesuit.

Arguments About Earth's Motion

A big part of the New Almagest (343 pages!) was about a huge question: Does the Earth move or stay still? Riccioli looked at 126 arguments about Earth's motion. He found 49 arguments that seemed to support Earth's motion and 77 arguments against it.

For Riccioli, the main debate wasn't between the old Earth-centered system of Ptolemy and the Sun-centered system of Copernicus. The telescope had already shown that Ptolemy's ideas were wrong. Instead, the debate was between the Sun-centered system of Copernicus and a system by Tycho Brahe. Brahe's system said the Sun, Moon, and stars orbit the Earth, while the other planets orbit the Sun. Riccioli liked a changed version of Brahe's system.

Many writers talk about Riccioli's 126 arguments. Let's look at a few key ones:

The "Physico-Mathematical" Argument

Riccioli discussed an argument related to Galileo's ideas about falling objects. Galileo had suggested that a falling stone's motion was a mix of the Earth's daily spin and the stone's own circular motion. Riccioli showed that this idea didn't work. He argued that if Galileo's idea were true, objects would fall much slower than they actually do.

The "Coriolis Effect" Argument

Riccioli also argued that if the Earth spun, it should affect how cannonballs fly. He said that if a cannon fired a ball towards the North Pole, the ball should land a little to the east (right) of the target. This is because the ground moves slower closer to the poles. He believed that if this effect happened, expert cannoneers would have noticed it. Since they hadn't, he argued the Earth must not be spinning.

Riccioli was right that such an effect would occur. Today, we call it the Coriolis effect. However, the effect is so tiny that cannoneers in his time could not have detected it.

The Star Size Argument

Riccioli used telescope observations of stars to argue against the Earth moving. Through the telescopes of his time, stars looked like small, distinct disks. These disks were actually just blurry images caused by the telescope itself. But back then, people thought these were the actual sizes of the stars.

If the Earth moved around the Sun, stars had to be incredibly far away to explain why their positions didn't seem to shift. Riccioli measured these star disks and calculated how big the stars would have to be if they were that far away. His results showed that the stars would be enormous, much bigger than the Sun. Some would even be larger than the entire universe as people imagined it then! This problem made it hard for many to believe the Earth moved.

Other Arguments

Riccioli's other arguments covered many topics. He wondered if buildings could stand or birds could fly if the Earth rotated. He also thought about what kind of motion was natural for heavy objects. Many of his arguments against the Sun-centered system came from the ideas of Tycho Brahe.

Riccioli strongly argued against the Sun-centered system. However, he also disagreed with some anti-Copernican arguments. For example, he said that if the Earth rotated, people wouldn't necessarily feel it, and buildings wouldn't fall apart. Some historians think that Riccioli might have secretly believed in the Sun-centered theory but had to pretend to oppose it because of his position as a Jesuit.

Astronomia Reformata

Another important book by Riccioli was his 1665 Astronomia Reformata (Reformed Astronomy). This book was like a shorter, updated version of his New Almagest.

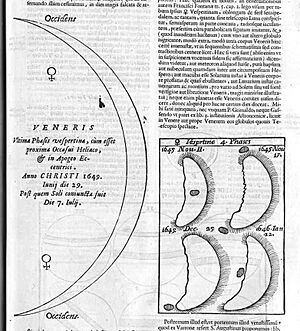

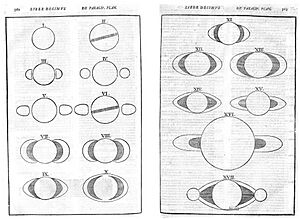

In this book, Riccioli wrote a lot about how Saturn's appearance changes. He also included a very early observation of Jupiter's Great Red Spot, seen in 1632. He also reported that Jupiter's cloud belts seemed to appear and disappear over time.

The Reformed Astronomy also led to a debate with another scientist, Stefano degli Angeli. This discussion about falling objects later caught the attention of Isaac Newton, which helped him focus on his own studies of how things move. In this book, Riccioli also included Kepler's idea that planets move in oval (elliptical) paths, even though he still didn't believe the Earth moved around the Sun.

Other Work

Between 1644 and 1656, Riccioli worked on measuring the Earth's size and the amount of water versus land. However, his measurements were not as accurate as others at the time.

He is often given credit for being one of the first to see that the star Mizar was actually a double star through a telescope. However, other astronomers like Castelli and Galileo had seen it much earlier.

Riccioli was a very respected scientist. He was known for his vast knowledge and his ability to understand and discuss all the important ideas in astronomy and geography of his time.

Selected Works

Riccioli's books were written in Latin.

Astronomy

- Geographicae crucis fabrica et usus ad repraesentandam ... omnem dierum noctiumque ortuum solis et occasum (1643) (Map of the world from Gallica)

- Almagestum novum astronomiam veterem novamque complectens (Volume I–III, 1651)

- Geographiæ et hydrographiæ reformatæ libri duodecim at Google Books, Bologna, 1661

- Astronomia reformata (Volume I–II, 1665)

- Vindiciae calendarii Gregoriani adversus Franciscum Leveram (1666)

- Apologia R.P. Io. Bapt. Riccioli Societatis Iesu pro argumento physicomathematico contra systema Copernicanum (1669)

- Chronologiae reformatae et ad certas conclusiones redactae ... (Volume I–IV, 1669)

- Tabula latitudinum et longitudinum (1689)

Theology

- Evangelium unicum Domini nostri Jesu Christi ex verbis ipsis quatuor Evangelistarum conflatum et in meditationes distributum at Google Books. Bologna, 1667.

- Immunitas ab errore tam speculativo quam practico definitionum s. Sedis apostolicae in canonizatione sanctorum, Bologna, 1668.

- De distinctionibus entium in Deo et in creaturis tractatus philosophicus ac theologicus (1669)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Giovanni Riccioli para niños

In Spanish: Giovanni Riccioli para niños

- List of Jesuit scientists

- List of Roman Catholic scientist-clerics

- Grimaldi (crater)

- Riccioli (crater)

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |