Almagest facts for kids

The Almagest is a very old and important book about math and space. It was written by a smart person named Claudius Ptolemy around 150 AD. This book explained how the stars and planets seemed to move in the sky.

The Almagest was one of the most important science books ever written. For over 1,200 years, people believed its idea that the Earth was the center of the Universe. This idea is called the geocentric model. People in ancient Alexandria, the Byzantine Empire, the Islamic world, and Europe during the Middle Ages and early Renaissance all followed Ptolemy's ideas. It was only when Copernicus came along that this idea started to change. The Almagest also helps us learn a lot about ancient Greek astronomy.

Ptolemy finished writing the Almagest around 150 AD. He had been watching the sky for about 25 years before that.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name Almagest comes from the Arabic word "al-majisṭī." The word "al" means "the," and "majisṭī" comes from a Greek word meaning "greatest."

The book's first Greek name was "Mathēmatikē Syntaxis," which means "Mathematical Arrangement." It was also called "Syntaxis Mathematica" in Latin. Later, people called it "Hē Megalē Syntaxis," or "The Great Treatise." The Arabic name "al-majisṭī" came from the Greek word for "greatest." This Arabic name became very important because a Latin translation of the book, called Almagestum, was made from an Arabic version in the 1100s. This Latin version was used for a long time until original Greek copies were found again in the 1400s.

What's Inside the Book?

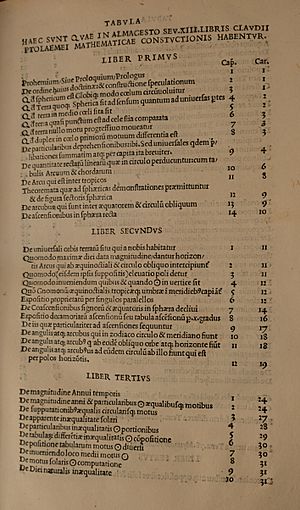

The Syntaxis Mathematica has thirteen parts, called books. Old handwritten books often had small differences between copies. Here's a simple look at what each book covers:

- Book I talks about Aristotle's ideas of the universe. It says the heavens are like a ball, and the Earth is a still ball at the center. The fixed stars and planets move around the Earth. This book also explains how to use chords in geometry and introduces spherical trigonometry, which is math for shapes on a sphere.

- Book II looks at how things in the sky move each day. It covers when stars and planets rise and set, how long the day is, and how to figure out your location on Earth. It also explains how the Sun's path changes with the seasons.

- Book III discusses the length of the year and how the Sun moves. Ptolemy explains a discovery by Hipparchus about how the Earth's axis slowly wobbles, which changes where the equinoxes are. He also starts to explain the idea of epicycles, which are small circles planets move on.

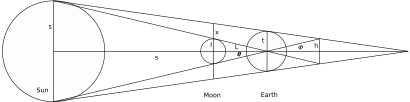

- Books IV and V are all about the Moon. They cover how the Moon moves, how its position seems to shift depending on where you are (called parallax), and how far away the Sun and Moon are from Earth.

- Book VI explains how solar eclipses and lunar eclipses happen.

- Books VII and VIII talk about the movements of the fixed stars. They include a star catalogue with 1022 stars. This list describes where each star is in its constellation and its exact position in the sky.

- Book IX deals with how to create models for the five planets you can see without a telescope. It also focuses on the movement of Mercury.

- Book X explains the movements of Venus and Mars.

- Book XI covers the movements of Jupiter and Saturn.

- Book XII explains "retrograde motion." This is when planets seem to stop and then move backward for a short time against the background of the stars. Ptolemy knew this happened for Mercury, Venus, and the outer planets.

- Book XIII talks about how planets move up and down, away from the main path of the Sun in the sky.

Ptolemy's View of the Universe

Ptolemy's book explains five main ideas about the universe:

- The sky is shaped like a ball and moves like a ball.

- The Earth is also shaped like a ball.

- The Earth is exactly in the middle of the universe.

- Compared to how far away the stars are, the Earth is tiny, like a single point.

- The Earth does not move at all.

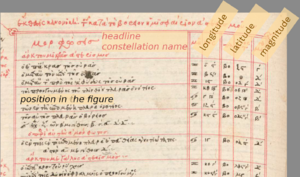

The Star Catalogue

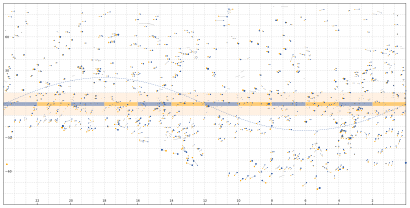

The star catalogue in the Almagest is set up like a table. It lists the exact positions of stars. Ptolemy chose to use a special coordinate system because he knew about the Earth's wobble (precession). This star catalogue is the oldest one we have that gives full tables of star positions and brightness.

Ptolemy said he listed 1022 stars, including even the dimmest ones you can see without a telescope. He also said the star positions were for the year 138 AD. However, later calculations showed that the star positions in his catalogue actually match up better with stars from around 50 AD.

Scientists have looked into why there's this difference:

- Some think Ptolemy used older observations from Hipparchus and made a small math error when updating them.

- Others think the data might have been observed earlier by another astronomer.

- It could also be a mix of small errors, including using old information about the Sun.

- Another idea is that Ptolemy's own measuring tools were not perfectly set up.

Even if we correct for the main error, there are still other small mistakes in the star positions. Some of these might be because of how light bends when it enters Earth's atmosphere, making stars look higher than they are. Some stars, like those in Centaurus, are off by a couple of degrees. This might mean they were measured by different people or in a less accurate way.

Constellations in the Star Catalogue

The star catalogue lists 48 constellations. These constellations have different sizes and numbers of stars. Ptolemy said that these constellations should be drawn on a globe. We don't have any drawings from his time, but we can recreate them today. This is because Ptolemy wrote down the exact positions of the heads, feet, arms, and other parts of the constellation figures.

These 48 constellations are the basis for the modern constellations we use today. The International Astronomical Union officially adopted their boundaries in 1928.

About 108 stars in the catalogue were called "unformed" by Ptolemy. This meant they were outside the main constellation shapes. Later, these stars were added to nearby constellations or used to create new ones.

Ptolemy's Planetary Model

Ptolemy arranged the planets in a specific order, starting from the one closest to Earth:

- Moon

- Mercury

- Venus

- Sun

- Mars

- Jupiter

- Saturn

- Sphere of fixed stars

Other ancient writers had different ideas about the order of the planets. But most astronomers in the Middle Ages in Islamic countries and Europe followed Ptolemy's order.

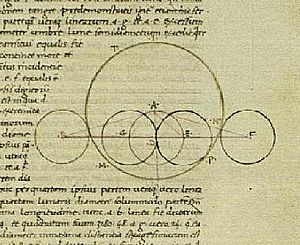

Ptolemy used ideas from earlier Greek astronomers. For example, Apollonius of Perga had introduced the ideas of deferent and epicycle (a planet moving on a small circle, which itself moves on a larger circle). Hipparchus had created good math models for the Sun and Moon. Hipparchus also knew about astronomy from Mesopotamia (ancient Iraq) and wanted Greek models to be as accurate as theirs. But he couldn't make accurate models for the other five planets.

Ptolemy used Hipparchus's model for the Sun. For the Moon, Ptolemy started with Hipparchus's idea and added a special "crank mechanism." Ptolemy succeeded where Hipparchus failed for the other planets by adding a third idea called the equant.

The Almagest was written as a textbook for mathematical astronomy. It showed how to use circles to predict how planets move. In another book, called Planetary Hypotheses, Ptolemy explained how to turn his math models into real 3D spheres.

How the Almagest Changed the World

Ptolemy's detailed book about astronomy became more important than most older Greek astronomy books. Some older books were too specific, and others just became outdated. Because of this, people stopped copying the older books, and many were lost. Much of what we know about astronomers like Hipparchus comes from what Ptolemy wrote in the Almagest.

The Almagest was first translated into Arabic in the 800s. One translation was even paid for by a ruler named Al-Ma'mun.

The first Latin translation wasn't made until the 1100s. Henry Aristippus made a translation directly from Greek. But a later translation into Latin by Gerard of Cremona from an Arabic version (finished in 1175) became more famous. Gerard worked in Spain at the Toledo School of Translators.

In the 1400s, a Greek version of the Almagest appeared in Western Europe. A German astronomer named Regiomontanus made a shorter Latin version. Around the same time, George of Trebizond made a full translation with a very long explanation. George's translation was much better than the old one.

Modern Versions

The Almagest has been edited and translated many times. A famous Greek edition was made by J. L. Heiberg in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Three English translations of the Almagest have been published. One was by R. Catesby Taliaferro in 1952. Another, by G. J. Toomer, was published in 1984 and again in 1998. A partial translation by Bruce M. Perry came out in 2014.

See Also

- Abū al-Wafā' Būzjānī (who also wrote an Almagest)

- Book of Fixed Stars

- Star cartography

- Euclid's Elements

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |